полная версия

полная версияThe Dangerous Classes of New York, and Twenty Years' Work Among Them

The same device, and constant instruction, broke up gambling, though I think policy-tickets were never fairly undermined among them.

The present Superintendent and Matron of the Newsboys' Lodging-house, Mr. and Mrs. O'Connor (at Nos. 49 and 51 Park Place), are unsurpassed in such institutions in their discipline, order, good management, and excellent housekeeping. The floors, over which two hundred or two hundred and fifty street-boys tread daily, are as clean as a man-of-war's deck. The Sunday-evening meetings are as attentive and orderly as a church, the week-evening school quiet and studious. All that mass of wild young humanity is kept in perfect order, and brought under a thousand good influences.

The Superintendent has had a very good preliminary experience for this work in the military service – having been in the British army in the Crimea. The discipline which he maintains is excellent. He is a man, too, of remarkable generosity of feeling, and a good "provider." One always knows that his boys will have enough to eat, and that everything will be managed liberally – and justly. It is truly remarkable during how many years he controlled that great multitude of little vagabonds and "roughs," and yet with scarcely ever even a complaint from any source against him. For such success is needed the utmost kindness, and, at the same time, the strictest justice. His wife has been almost like a mother to the boys.

In the course of a year the population of a town passes through the Lodging-house – in 1869 and '70, eight thousand eight hundred and thirty-five different boys. Many are put in good homes; some find places for themselves; others drift away – no one knows whither. They are an army of orphans – regiments of children who have not a home or friend – a multitude of little street-rovers who have no place where to lay their heads. They are being educated in the streets rapidly to be thieves and burglars and criminals. The Lodging-house is at once school, church, intelligence-office, and hotel for them. Here they are shaped to be honest and industrious citizens; here taught economy, good order, cleanliness, and morality; here Religion brings its powerful influences to bear upon them; and they are sent forth to begin courses of honest livelihood.

The Lodging-houses repay their expenses to the public ten times over each year, in preventing the growth of thieves and criminals. They are agencies of pure humanity and almost unmingled good. Their only possible reproach could be, that some of their wild subjects are soon beyond their reach, and have been too deeply tainted with the vices of street-life to be touched even by kindness, education, or religion. The number who are saved, however, are most encouragingly large.

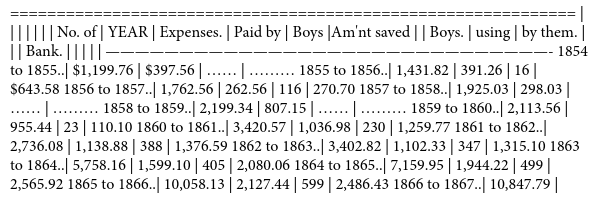

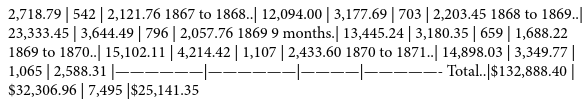

The Newsboys' Lodging-house is by no means, however, an entire burden on the charity of the community. During 1870 the lads themselves paid $3,349 toward its expense.

The following is a brief description of the rooms during the past five years:

The first floor is divided into various compartments – a large dining-room, where one hundred and fifty boys can sit down to a table; a kitchen, laundry, storeroom, servants' room, and rooms for the family of the superintendent The next story is partitioned into a school-room, gymnasium, and bath and wash rooms, plentifully supplied with hot and cold water. The hot water and the heat of the rooms are supplied by a steam-boiler on the lower story. The two upper stories are filled with neat iron bedsteads, having two beds each, arranged like ships' bunks over each other; of these there are two hundred and sixty. Here are also the water-vats, into which the many barrelsful used daily are pumped by the engine. The rooms are high and dry, and the floors clean.

It is a commentary on the housekeeping and accommodations that for eighteen years no case of contagious disease has ever occurred among these thousands of boys.

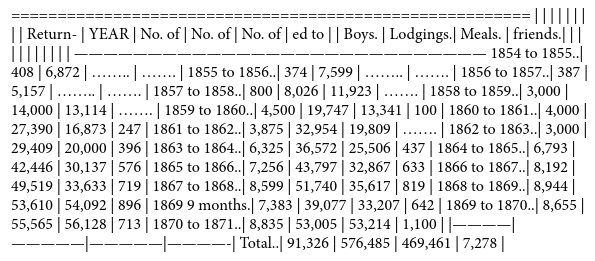

The New York Newsboys' Lodging-house has been in existence eighteen years. During these years it has lodged 91,326 different boys, restored 7,278 boys to friends, provided 5,126 with homes, furnished 576,485 lodgings and 469,461 meals. The expense of all this has been $132,888. Of this amount the boys have contributed $32,306.

That the Lodging-house has had a vigorous growth, is shown by the following table:

TABULAR STATEMENT SINCE ORGANIZATION

Extracts from the journal of a visitor from the country:

A VISIT TO THE NEWSBOYS"It requires a peculiar person to manage and talk to these boys. Bullet-headed, short-haired, bright-eyed, shirt-sleeved, go-ahead boys. Boys who sell papers, black boots, run on errands, hold horses, pitch pennies, sleep in barrels, and steal their bread. Boys who know at the age of twelve more than the children of ordinary men would have learned at twenty; boys who can cheat you out of your eye-teeth, and are as smart as a steel-trap. They will stand no fooling; they are accustomed to gammon, they live by it. No audience that ever we saw could compare in attitudinizing with this. Heads generally up; eyes fall on the speaker; mouths, almost without an exception, closed tightly; hands in pockets; legs stretched out; no sleepers, all wide-awake, keenly alive for a pun, a point, or a slangism. Winding up, Mr. Brace said: 'Well, boys, I want my friends here to see that you have the material for talkers amongst yourselves; whom do you choose for your orator?'

"'Paddy, Paddy,' shouted one and all. 'Come out, Paddy. Why don't you show yourself?' and so on.

"Presently Paddy came forward, and stood upon a stool. He is a youngster, not more than twelve, with a little round eye, a short nose, a lithe form, and chuck-full of fun.

"'Bummers,' said he, 'snoozers, and citizens, I've come down here among ye to talk to yer a little! Me and my friend Brace have come to see how ye'r gittin' along, and to advise yer. You fellers what stands at the shops with yer noses over the railin', smellin' ov the roast beef and the hash – you fellers who's got no home – think of it how we are to encourage ye. [Derisive laughter, "Ha-ha's," and various ironical kinds of applause.] I say, bummers – for you're all bummers (in a tone of kind patronage) —I was a bummer once [great laughter] – I hate to see you spendin' your money on penny ice-creams and bad cigars. Why don't you save your money? You feller without no boots, how would you like a new pair, eh? [Laughter from all the boys but the one addressed.] Well, I hope you may get 'em, but I rayther think you won't. I have hopes for you all. I want you to grow up to be rich men – citizens, Government men, lawyers, generals, and influence men. Well, boys, I'll tell you a story. My dad was a hard 'un. One beautiful day he went on a spree, and he came home and told me where's yer mother? and I axed him I didn't know, and he clipt me over the head with an iron pot, and knocked me down, and me mither drapped in on him, and at it they went. [Hi-hi's, and demonstrative applause.] Ah! at it they went, and at it they kept – ye should have seen 'em – and whilst they were fightin', I slipped, meself out the back door, and away I went like a scart dog. [Oh, dry up! Bag your head! Simmer down!] Well, boys, I wint on till I kim to the 'Home' [great laughter among the boys], and they took me in [renewed laughter], and did for me, without a cap to me head or shoes to me feet, and thin I ran away, and here I am. Now boys [with mock solemnity], be good, mind yer manners, copy me, and see what you'll become.'

"At this point the boys raised such a storm of hifalutin applause, and indulged in such characteristic demonstrations of delight, that it was deemed best to stop the youthful Demosthenes, who jumped from his stool with a bound that would have done credit to a monkey.

"At this juncture huge pans of apples were brought in, and the boys were soon engaged in munching the delightful fruit, after which the Matron gave out a hymn, and all joined in singing it, during which we took our leave."

A NEWSBOY'S SPEECH. (FROM OUR JOURNAL.)"Some of these boys, in all their misfortunes, have a humorous eye for their situation – as witness the following speech, delivered by one of them at the Newsboys' Lodging-house, before the departure of a company to the West. The report is a faithful one, made on the spot. The little fellow mounted a chair, and thus held forth:

"'Boys, gintlemen, chummies: Praps you'd like to hear summit about the West, the great West, you know, where so many of our old friends are settled down and growin' up to be great men, maybe the greatest men in the great Republic. Boys, that's the place for growing Congressmen, and Governors, and Presidents. Do you want to be newsboys always, and shoeblacks, and timber-merchants in a small way by sellin' matches? If ye do you'll stay in New York, but if you don't you'll go out West, and begin to be farmers, for the beginning of a farmer, my boys, is the making of a Congressman, and a President. Do you want to be rowdies, and loafers, and shoulder-hitters? If ye do, why, ye can keep around these diggins. Do you want to be gentlemen and independent citizens? You do – then make tracks for the West, from the Children's Aid Society. If you want to be snoozers, and rummeys, and policy-players, and Peter Funks men, why you'll hang up your caps and stay round the groceries and jine fire-engine and target companies, and go firin' at haystacks for bad quarters; but if ye want to be the man who will make his mark in the country, ye will get up steam, and go ahead, and there's lots on the prairies a waitin' for yez.

"'You haven't any idear of what ye may be yet, if you will only take a bit of my advice. How do you know but, if you are honest, and good, and industerous, you may get so much up in the ranks that you won't call a gineral or a judge your boss. And you'll have servants ov all kinds to tend you, to put you to bed when you are sleepy, and to spoon down your vittles when you are gettin' your grub. Oh, boys! won't that be great! Only think – to have a feller to open your mouth, and put great slices of punkin pie and apple dumplings into it. You will be lifted on hossback when you go for to take a ride on the prairies, and if you choose to go in a wagon, or on a 'scursion, you will find that the hard times don't touch you there; and the best of it will be that if 'tis good to-day, 'twill be better to-morrow.

"But how will it be if you don't go, boys? Why, I'm afraid when you grow too big to live in the Lodging-house any longer, you'll be like lost sheep in the wilderness, as we heard of last Sunday night here, and you'll maybe not find your way out any more. But you'll be found somewhere else. The best of you will be something short of judges and governors, and the feller as has the worst luck – and the worst behaver in the groceries-will be very sure to go from them to the prisons.

"I will now come from the stump. I am booked for the West in the next company from the Lodging-house. I hear they have big school-houses and colleges there, and that they have a place for me in the winter time; I want to be somebody, and somebody don't live here, no how. You'll find him on a farm in the West, and I hope you'll come to see him soon and stop with him when you go, and let every one of yous be somebody, and be loved and respected. I thank yous, boys, for your patient attention. I can't say more at present, I hope I haven't said too much.'"

THE BUILDING FUNDAn effort was made in the Legislature, a few years since, to obtain a building-fund for the Newsboys' Lodging-house. This was granted from the Excise Fund of the city for the legitimate reason, that those who do most to form drunkards should be compelled to aid in the expense and care of the children of drunkards. Thirty thousand dollars were appropriated from these taxes, provided a similar amount was raised by private subscription. This sum was obtained by the kindness and energy of the friends of the enterprise, and the whole amount ($60,000) was invested in good securities.

In 1872 it had accumulated to $80,000, and the purchase was made of the "Shakespeare Hotel," on the corner of Duane and Chambers Streets, which is now being fitted up and rebuilt as a permanent Lodging-house for Homeless Boys. The building has streets on three sides, and, plenty of air and light. Shops will be let underneath, so that the payments of the boys and the rents received will nearly defray the annual expenses of this charity, thus insuring its permanency.

CHAPTER X

STREET GIRLSTHEIR SUFFERINGS AND CRIMESA girl street-rover is to my mind the most painful figure in all the unfortunate crowd of a large city. With a boy, "Arab of the streets," one always has the consolation that, despite his ragged clothes and bed in a box or hay-barge, he often has a rather good time of it, and enjoys many of the delicious pleasures of a child's roving life, and that a fortunate turn of events may at any time make an honest, industrious fellow of him. At heart we cannot say that he is much corrupted; his sins belong to his ignorance and his condition, and are often easily corrected by a radical change of circumstances. The oaths, tobacco-spitting, and slang, and even the fighting and stealing of a street-boy, are not so bad as they look. Refined influences, the checks of religion, and a fairer chance for existence without incessant struggle, will often utterly eradicate these evil habits, and the rough, thieving New York vagrant make an honest, hardworking Western pioneer. It is true that sometimes the habit of vagrancy and idling may be too deeply worked in him for his character to speedily reform; but, if of tender years, a change of circumstances will nearly always bring a change of character.

With a girl-vagrant it is different. She feels homelessness and friendlessness more; she has more of the feminine dependence on affection; the street-trades, too, are harder for her, and the return at night to some lonely cellar or tenement-room, crowded with dirty people of all ages and sexes, is more dreary. She develops body and mind earlier than the boy, and the habits of vagabondism stamped on her in childhood are more difficult to wear off.

Then the strange and mysterious subject of sexual vice comes in. It has often seemed to me one of the most dark arrangements of this singular world that a female child of the poor should be permitted to start on its immortal career with almost every influence about it degrading, its inherited tendencies overwhelming toward indulgence of passion, its examples all of crime or lust, its lower nature awake long before its higher, and then that it should be allowed to soil and degrade its soul before the maturity of reason, and beyond all human possibility of cleansing!

For there is no reality in the sentimental assertion that the sexual sins of the lad are as degrading as those of the girl. The instinct of the female is more toward the preservation of purity, and therefore her fall is deeper – an instinct grounded in the desire of preserving a stock, or even the necessity of perpetuating our race.

Still, were the indulgences of the two sexes of a similar character – as in savage races – were they both following passion alone, the moral effect would not perhaps be so different in the two cases. But the sin of the girl soon becomes what the Bible calls "a sin against one's own body," the most debasing of all sins. She soon learns to offer for sale that which is in its nature beyond all price, and to feign the most sacred affections, and barter with the most delicate instincts. She no longer merely follows blindly and excessively an instinct; she perverts a passion and sells herself. The only parallel case with the male sex would be that in some Eastern communities which are rotting and falling to pieces from their debasing and unnatural crimes. When we hear of such disgusting offenses under any form of civilization, whether it be under the Rome of the Empire, or the Turkey of to-day, we know that disaster, ruin, and death, are near the State and the people.

This crime, with the girl, seems to sap and rot the whole nature. She loses self-respect, without which every human being soon sinks to the lowest depths; she loses the habit of industry, and cannot be taught to work. Having won her food at the table of Nature by unnatural means, Nature seems to cast her out, and henceforth she cannot labor. Living in a state of unnatural excitement, often worked up to a high pitch of nervous tension by stimulants, becoming weak in body and mind, her character loses fixedness of purpose and tenacity and true energy. The diabolical women who support and plunder her, the vile society she keeps, the literature she reads, the business she has chosen or fallen into, serve continually more and more to degrade and defile her. If, in a moment of remorse, she flee away and take honest work, her weakness and bad habits follow her; she is inefficient, careless, unsteady, and lazy; she craves the stimulus and hollow gayety of the wild life she has led; her ill name dogs her; all the wicked have an instinct of her former evil courses; the world and herself are against reform, and, unless she chance to have a higher moral nature or stronger will than most of her class, or unless Religion should touch even her polluted soul, she soon falls back, and gives one more sad illustration of the immense difficulty of a fallen woman rising again.

The great majority of prostitutes, it must be remembered, have had no romantic or sensational history, though they always affect this. They usually relate, and perhaps even imagine, that they have been seduced from the paths of virtue suddenly and by the wiles of some heartless seducer. Often they describe themselves as belonging to some virtuous, respectable, and even wealthy family. Their real history, however, is much more commonplace and matter-of-fact. They have been poor women's daughters, and did not want to work as their mothers did; or they have grown up in a tenement-room, crowded with boys and men, and lost purity before they knew what it was; or they have liked gay company, and have had no good influences around them, and sought pleasure in criminal indulgences; or they have been street-children, poor, neglected, and ignorant, and thus naturally and inevitably have become depraved women. Their sad life and debased character are the natural outgrowth of poverty, ignorance, and laziness. The number among them who have "seen better days," or have fallen from heights of virtue, is incredibly small. They show what fruits neglect in childhood, and want of education and of the habit of labor, and the absence of pure examples, will inevitably bear. Yet in their low estate they always show some of the divine qualities of their sex. The physicians in the Blackwell's Island Hospital say that there are no nurses so tender and devoted to the sick and dying as these girls. And the honesty of their dealings with the washerwomen and shopkeepers, who trust them while in their vile houses, has often been noted.

The words of sympathy and religion always touch their hearts, though the effect passes like the April cloud. On a broad scale, probably no remedy that man could apply would ever cure this fatal disease of society. It may, however, be diminished in its ravages, and prevented in a large measure. The check to its devastations in a laboring or poor class will be the facility of marriage, the opening of new channels of female work, but, above all, the influences of education and Religion.

An incident occurred daring our early labors, which is worth preserving:

EXTRACTS FROM JOURNAL DURING 1854THE TOMBS"Mrs. Forster, the excellent Matron of the Female Department of the prison, had told us of an interesting young German girl, committed for vagrancy, who might just at this crisis be rescued. I entered these soiled and gloomy Egyptian archways, so appropriate and so depressing, that the sight of the low columns and lotus capitals is to me now inevitably associated with the somber and miserable histories of the place.

"After a short waiting, the girl was brought in – a German girl, apparently about fourteen, very thinly but neatly dressed, of slight figure, and a face intelligent and old for her years, the eye passionate and shrewd. I give details because the conversation which followed was remarkable.

"The poor feel, but they can seldom speak. The story she told, with a wonderful eloquence, thrilled to all our hearts; it seemed to us, then, like the first articulate voice from the great poor class of the city.

"Her eye had a hard look at first, but softened when I spoke to her in her own language.

"'Have you been long here?'

"'Only two days, sir.'

"Why are you here?'

"'I will tell you, sir. I was working out with a lady. I had to get up early and go to bed late, and I never had rest. She worked me always; and, finally, because I could not do everything, she beat me – she beat me like a dog, and I ran away; I could not bear it.'

"The manner of this was wonderfully passionate and eloquent.

"'But I thought you were arrested for being near a place of bad character,' said I.

"'I am going to tell you, sir. The next day I and my father went to get some clothes I left there, and the lady wouldn't give them up; and what could we do? What can the poor do? My father is a poor old man, who picks rags in the streets, and I have never picked rags yet. He said, "I don't want you to be a rag-picker. You are not a child now – people will look at you – you will come to harm." And I said, "No, father, I will help you. We must do something now, I am out of place;" and so I went out. I picked all day, and didn't make much, and I was cold and hungry. Towards night, a gentleman met me – a very fine, well-dressed gentleman, an American, and he said, "Will you go home with me!" and I said, "No." He said, "I will give you twenty shillings," and I told him I would go. And the next morning I was taken up outside by the officer.'

"'Poor girl!' said some one, 'had you forgotten your mother? and what a sin it was!'

"'No, sir, I did remember her. She had no clothes, and I had no shoes; and I have only this (she shivered in her thin dress), and winter is coming on. I know what making money is, sir. I am only fourteen, but I am old enough. I have had to take care of myself ever since I was ten years old, and I have never had a cent given me. It may be a sin, sir (and the tears rained down her cheeks, which she did not try to wipe away). I do not ask you to forgive it. Men can't forgive, but God will forgive. I know about men.

"'The rich do such things and worse, and no one says anything against them. But I, sir —I am poor! (This she said with a tone which struck the very heart-strings.) I have never had any one to take care of me. Many is the day I have gone hungry from morning till night, because I did not dare spend a cent or two, the only ones I had. Oh, I have wished sometimes so to die! Why does not God kill me!'

"She was choked by her sobs. We let her calm herself a moment, and then told her our plan of finding her a good home, where she could make an honest living. She was mistrustful. 'I will tell you, mein Herren; I know men, and I do not believe any one, I have been cheated so often. There is no trust in any one. I am not a child. I have lived as long as people twice as old.'

"'But you do not wish to stay in prison?'

"'O God, no! Oh, there is such a weight on my heart here. There is nothing but bad to learn in prison. These dirty Irish girls! I would kill myself if I had to stay here. Why was I ever born? I have such Kummerniss (woes) here (she pressed her hand on her heart) – I am poor!'

"We explained our plan more at length, and she became satisfied. We wished her to be bound to stay some years.

"'No,' said she, passionately, 'I cannot; I confess to you, gentlemen. I should either run away or die, if I was bound.'

"We talked with the matron. She had never known, she said, in her experience, such a remarkable girl. The children there of nine or ten years were often as old as young women, but this girl was an experienced woman. The offense, however, she had no doubt was her first.