полная версия

полная версияThe Dangerous Classes of New York, and Twenty Years' Work Among Them

One mistake of Sunday-school oratory is frequently made in addressing these lads, and that is, a too great use of sensational illustrations, which do not aid to impress the truth desired. Attention will be secured, but no good end is gained. Where the wants of the audience are so real and terrible as they are here, and so little time is given for influencing them, it is of the utmost importance that every word should tell. There should be no rhetorical pyrotechnics at these meetings. Above all modes, however, the dramatic is the best means of conveying truth to their minds. The parable, the illustration, the allegory or story, real or fictitious, most quickly strike their mind, and leave the most permanent impression.

One of the best religious speakers that ever address our boys is a lawyer, who has been a famous sportsman, and has in his constitution a fellow-feeling for their vagrant tastes. I often fancy, when he is speaking to them, that he would not object at all to being a boy again himself, roving the streets, "turning in" on a hay-barge, and drifting over the country at "his own sweet will." But this very sympathy gives him a peculiar power over them; he understands their habits and temptations, and, while other gentlemen often shoot over their heads, his words always take a powerful hold of them. Then, though a man particularly averse to sentiment in ordinary life, his speeches to the boys seem to reveal a deep and poetic feelings for nature, and a solemn consciousness of God, which impresses children deeply. His sportsmanly habits have led him to closely observe the habits of birds and animals, and the appearances of the sky and sea, and these come in as natural illustrations, possessing a remarkable interest for these wild little vagrants, who by nature belong to the "sporting" class.

A man must have a boy's tastes to reach boys.

BIBLE IN SCHOOLSIn treating of this subject of religious education for the youth of the dangerous classes, the question naturally arises, how far there should be religious expression or education in our Public Schools. If it were a tabula rasa here, and we were opening a system of National Schools, and all were of one general faith, there could be no question that every one interested in the general welfare, would desire religious instruction in our Public Schools, as a means of strengthening morality, if for no other purpose. As it is, however, we have at the basis of society an immense mass of very ignorant, and, therefore, bigoted people, who suspect and hate every expression even of our form of Christianity, and regard it as a teaching of heresy and a shibboleth of oppression. Their shrewd and cunning leaders, knowing the danger to priestcraft from Free Schools, use this hostility and the pretense of our religious services to separate these classes from the Public Schools. The priests and demagogues do not, of course, care anything about the simple prayer and the reading of a few verses of Scripture, which are now our sole religious school exercises. But these furnish them with a good pretext for acting on the masses, and give them ground, among certain liberal or indifferent Protestants, for seeking a separate State support for the Catholic Schools.

Were Bible-reading and the Lord's Prayer discontinued in the Schools, we do not doubt that the priests and the popular leaders would still oppose the Free Schools just as bitterly; but they would not have as good an apparent ground, and any pretext of opposition would be taken away. The system of Free Schools is the life-blood of the nation. If it be corrupted with priestcraft, or destroyed by our dissensions, our vitality as a republican people is gone. The whole country would realize then the worst fruits of a popular government without intelligence. Demagogism and corruption, founded on ignorance, would wield an absolute tyranny, with none of the graces of monarchy, and none of the advantages of democracy. Jarring sects would each have their own schools, and the priests would enjoy an unlimited control over all the ignorant Catholics of the country.

Under no circumstance should the Protestants of the nation allow the Free Schools to be broken up. They are the foundation of the Republic, and the bulwark of Protestantism and civilization. They undermine the power of the priests, which rests on ignorance, while they leave untouched whatever spiritual force the Roman Catholic Church may truly have and deserve to have. The Protestants should sacrifice everything reasonable and not vital, to retain these blessed agencies of enlightenment.

We respect the sort of pluck of the Protestants, which looks upon the giving-up of Bible-reading in the Schools as being "false to the flag." But, in looking at the matter soberly, and without pugnacity, does spiritual religion lose anything by giving up these exercises? We think not. They are now of the coldest and most formal kind, and but little listened to. We doubt if they ever affect strongly a single mind. The religious education of each child is imparted in Sabbath Schools, in Churches, or Mission Schools, and its own home.

The Free School under our system does not need any influence from the Church. The American trusts to the separate sects to take care of the religious interests of the children. We separate utterly Church and State. There may be evils from this; but they are less than the danger of destroying our system of popular education by the contests of rival sects. We know how long every effort to secure popular education for England has been wrecked on this rock of Sectarianism.

We behold the fearful harvest of evils which she is reaping from the ignorance of the masses, especially induced by the oppositions of sects, who preferred no education for the people to education without their own dogmas.

We desire to avoid these calamities, and we can best do this by making every reasonable concession to ignorance and prejudice.

Give us the Free Schools without Religion, rather than no Free Schools at all!

CHAPTER XXXVI

DECREASE OF JUVENILE CRIME IN NEW YORKTHE COST OF PUNISHMENT AND PREVENTIONVery few people have any just appreciation of the comparative cost of punishment and prevention in the treatment of crime. The writer recalls one out of many thousand instances in his experience, which strikingly illustrates the contrast

THE BROTHERSA number of years ago, three boys (brothers), the oldest perhaps seventeen, applied at the Newsboys' Lodging-house of this city for shelter. It was soon suspected that the eldest was a thief, employing the younger as assistants in his nefarious business. The younger lads finally confessed the fact, and the older brother left them to be taken care of in the Lodging-house. After a sufficient period of training, the two brothers were sent to a farmer in Illinois. They were faithful and hard-working, and soon began to earn money. When the war broke out they enlisted, and served with credit. At the close they passed through New York, and visited the superintendent while returning to their village, having already purchased a farm with their wages and bounty-money. They are now well-to-do, respectable farmers.

This "prevention" for the two lads cost just thirty dollars, for their expenses in the Lodging-house were mainly paid by themselves.

The older brother went through a career of thieving and burglary. We have not an accurate catalogue of his various offenses, but he undoubtedly made away with property – wasted or destroyed it – to the amount of two thousand dollars. [We recall three lads who, in one night, broke into a house in Bond Street, and destroyed or made away with property to the value of one thousand three hundred dollars.] He was finally arrested and tried for burglary. It would be safe to estimate the expenses of the trial and arrest at one hundred dollars. He was sentenced to five years in Sing Sing. Allowing the expenses of maintenance there to be what they are on Blackwell's Island, that is, about twelve dollars and fifty cents per month, he cost the State while there some seven hundred and fifty dollars, not reckoning the interest on capital and buildings; so that we have here, in one instance, the very low estimate of two thousand eight hundred and fifty dollars as the expense to the community of one street-boy unreclaimed. Had the Lodging-house taken hold of him five years earlier, he could have been saved at a cost of fifteen dollars.

His brothers have added to the wealth of the community and defended the life of the nation, and are still honest producers. He has already cost the State at least two thousand eight hundred and fifty dollars, besides much immorality and bad example, and he has only begun a career of damage and loss to the city.

PREVENTION AND PUNISHMENT COMPAREDOur criminals last year cost this city, in the City Prisons and Penitentiaries, about one hundred and one thousand dollars for maintenance alone. Our police cost apparently over six hundred thousand dollars.

The amount of property lost or taken by thieves, burglars, and others last year, in New York city, and which came under the knowledge of the police, was one million five hundred and twenty-one thousand nine hundred and forty dollars; but how many sums are never brought to their notice!

The expenses of the arrest and trial of two criminals, Real and Van Echten, are stated, on good authority, to have been sixteen thousand dollars for the first, and twenty thousand dollars for the second.

If the expenses of a great "preventive" institution – such as the Children's Aid Society – be examined, it will be found that the two thousand and odd homeless children, boys and girls, placed in country homes, cost the public only some fifteen dollars a head; the three thousand and odd destitute little girls educated and partly fed and clothed in the "Industrial Schools," only cost some fifteen dollars for each child each year; and the street lads and girls sheltered and instructed in the "Lodging-houses," to the number of some twelve thousand different subjects, or an average of, say, four hundred each night, have been an expense of only some fifty dollars per head through the year to the public. It may, perhaps, be urged in reply to this by the doubting, that all this may be true. "We admit the cheapness of prevention, but we do not see the diminution of crime. If you can show us that fewer young thieves, or vagabonds, or prostitutes, are breeding, we shall admit that your children's charities are doing something, and that the cost of prevention is the most paying outlay in the administration of New York city."

To this we might answer that New York is an exceptional city – a sink into which pour the crime and poverty of all countries, and that all we could expect to accomplish would be what is attempted in European cities – to keep the increase of juvenile crime down equal with the increase of population; that the laws of crime are shown in European cities to be constant, and that we must expect just about so many petty thieves each year, so many pickpockets, so many burglars, so many female vagrants or prostitutes, to so many thousand inhabitants.

We might urge that it is the duty of every friend of humanity to do his little part to alleviate the evils of the world, whether he sees a general diminution of human ills or not.

But, fortunately, we are not obliged to render these excuses.

New York is the only large city in the world where there has been a comprehensive organization to deal with the sources of crime among children; an organization which, though not reaching the whole of the destitute and homeless youth, and those most exposed to temptation, still includes a vast multitude every year of the enfants perdus of this metropolis.

This Association, during nearly twenty years, has removed to country homes and employment about twenty-five thousand persons, the greater part of whom have been poor and homeless children; it has founded, and still supports, five Lodging-houses for homeless and street-wandering boys and girls, five free Reading-rooms for boys and young men, and twenty Industrial Schools for children too poor, ragged, and undisciplined for the Public Schools. We have always been confident that time would show, even in the statistics of crime in our 19 prisons and police courts, the fruits of these very extended and earnest labors. It required several years to properly found and organize the Children's Aid Society, and then it must be some ten years-when the children acted upon in all its various branches have come to young manhood and womanhood – before the true effects are to be seen. We would not, however, exclude, as causes of whatever results may be traced, all similar movements in behalf of the youthful criminal classes. We may then fairly look, in the present and the past few years, for the effects on crime and pauperism of these widely-extended charities in behalf of children.

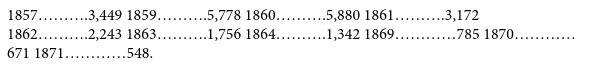

CRIME CHECKEDThe most important field of the Children's Aid Society has been among the destitute and street-wandering and tempted little girls, its labors embracing many thousands annually of this unfortunate class. Has crime increased with them? The great offense of this class, either as children or as young women, comes under the heading of "Vagrancy" – this including their arrest and punishment, either as street-walkers, or prostitutes, or homeless persons. In this there is, during the past thirteen years, a most remarkable decrease – a diminution of crime probably unexampled in any criminal records through the world. The rate in the commitments to the city prisons, as appears in the reports of the Board of Charities and Correction, runs thus: —

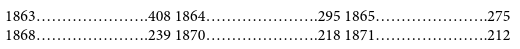

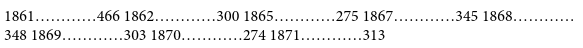

Of female vagrants, there were in

We have omitted some of the years on account of want of space; they do not, however, change the steady rate of decrease in this offense.

Thus, in eleven years, the imprisonments of female vagrants have fallen off from 5,880 to 548. This, surely, is a good show; and yet in that period our population increased about thirteen and a half per cent, so that, according to the usual law, the commitments should have been this year over 4,700. [The population of New York increased from 814,224, in 1860, to 915,520, in 1870, or only about twelve and a half per cent. The increase in the previous decade was about fifty per cent. There can be no doubt that the falling-off is entirely in the middle classes, who have removed to the neighboring rural districts. The classes from which most of the criminals come have undoubtedly increased, as before, at least fifty per cent.

I have retained for ten years, however, the ratio of the census, twelve and a half per cent.]

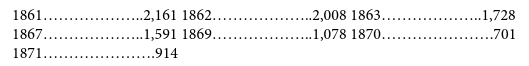

If we turn now to the reports of the Commissioners of Police, the returns are almost equally encouraging, though the classification of arrests does not exactly correspond with that of imprisonments; that is, a person may be arrested for vagrancy, and sentenced for some other offense, and vice versa.

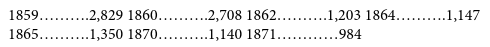

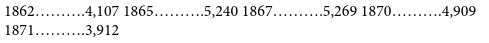

The reports of arrests of female vagrants ran thus: —

We have not, unfortunately, statistics of arrests farther back than 1861.

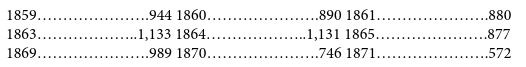

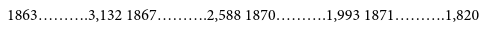

Another crime of young girls is thieving or petty larceny. The rate of commitments runs thus for females: —

The increase of this crime daring the war, in the years 1863 and 1864, is very marked; but in twelve years it has fallen from 944 to 572, though, according to the increase of the population, it would have been naturally 1,076.

Another heading on the prison records is "Juvenile delinquency," which may include any form of youthful offense not embraced in the other terms. Under this, in 1860, were two hundred and forty (240) females; in 1870, fifty-nine (59).

The classification of commitments of those under fifteen years only runs back a few years. The number of little girls imprisoned the past few years is as follows: —

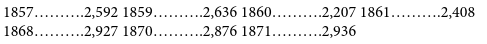

The imprisonment, of males, for offenses which boys are likely to commit, though not so encouraging as with the girls, shows that juvenile crime is fairly under control in this city. Thus, "Vagrancy" must include many of the crimes of boys; under this head we find the following commitments of males: —

In twelve years a reduction from 2,829 to 994, when the natural increase should have been up to 3,225.

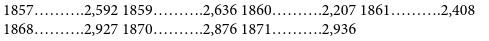

Petty larceny is a boy's crime; the record stands thus for males: —

A decrease in fourteen years of 502, when the natural increase should have brought the number to 2,861.

Of boys under fifteen imprisoned, the record stands thus since the new classification: —

Of males between fifteen and twenty, in our city prisons, the following is the record: —

It often happens that youthful criminals are arrested who are not imprisoned. The reports of the Board of Police will give us other indications that, even here, juvenile crime has at length been diminished in its sources.

ARRESTSThe arrests of pickpockets run thus since 1861, the limit of returns accessible: —

In ten years a reduction of 153 in the arrests of pickpockets.

In petty larceny the returns stand thus in brief: —

A decrease in nine years of 195.

Arrests of girls alone, under twenty: —

It must be plain from this, that crime among young girls is decidedly checked, and among boys is prevented from increasing with population.

If our readers will refer back to these dry but cheering tables of statistics, they will see what a vast sum of human misery saved is a reduction, in the imprisonment of female vagrants, of more than five thousand in 1871, as compared with 1869. How much homelessness and desperation spared! how much crime and wretchedness diminished are expressed in those simple figures! And, if we may reckon an average of punishment of two months' detention to each of those girls and women, we have one hundred and twenty-five thousand dollars saved in one year to the public by preventive agencies in this class of offenders alone.

The same considerations, both of economy and humanity, apply to each of the results that appear in these tables of crime and punishment.

No outlay of money for public purposes which any city or its inhabitants can make, repays itself half so well as its expenses for charities which prevent crime among children.

CHAPTER XXXVII

THE CAUSES OF THE SUCCESS OF THE WORKIn reviewing these long-continued efforts for the prevention of crime and the elevation of the neglected youth of this metropolis, it may aid others engaged in similar enterprises to note in summary the principles on which they have been carried out, and which account for their marked success.

In the first place, as has been so often said, though pre-eminently a Charity, this Association has always sought to encourage the principle of Self-help in its beneficiaries, and has aimed much more at promoting this than merely relieving suffering. All its branches, its Industrial Schools, Lodging-houses, and Emigration, aim to make the children of the poor better able to take care of themselves; to give them such a training that they shall be ashamed of begging, and of idle, dependent habits, and to place them where their associates are self-respecting and industrious. No institution of this Society can be considered as a shelter for the dependent and idle. All its objects of charity work, or are trained to work. The consequence is that this effort brings after it none of the bad fruits of mere alms-giving. The poor do not become poorer or less self-reliant under it; on the contrary, they are continually rising out of their condition and making their own way in the world. The laborer in this field does not feel, as in so many other philanthropic causes, doubtful, after many years of labor, whether he has not done as much injury as good. He sees constantly the wonderful effect of these efforts, and he knows that, at the worst, they can only fail of the best fruit, but certainly cannot have a bad result.

From the commencement our aim has been to put these charitable enterprises in harmony with natural and economic laws, assured that any other plan of philanthropy must eventually fail. In this view we have taken advantage of the immense demand for labor through our rural districts, which alone gives a new aspect to all economical problems in this country. Through this demand we have been enabled to accomplish our best results, with remarkable economy. We have been saved the vast expense of Asylums, and have put our destitute children in the child's natural place – with a family. Our Lodging-houses also have avoided the danger attending such places of shelter, of becoming homes for vagrant boys and girls. They have continually passed their little subjects along to the country, or to places of work, often forcing them to leave the house. In requiring the small payments for lodging and meals, they put the beneficiaries in an independent position, and check the habits and spirit of pauperism. The Evening School, the Savings-bank, and the Religious Meeting are continually acting on these children to raise them from the vagrant class. The Industrial Schools, in like manner, are seminaries of industry and teachers of order and self-help.

All the agencies of the Society act in harmony with natural laws, and touch the deepest springs of life and character. The forces underlying them are the strongest forces of society – Religion, Education, Self-respect, and love of Industry; these are constantly working upon the thousands of poor children under our charge. Thus founded on simple and natural principles, the Society has succeeded, because very earnest men and women have labored in it, and because its organization has been remarkably complete.

The employes have entered into its labors principally from love of its objects, and then have been retained by a just and liberal treatment on the part of the Trustees, and by each being made responsible for his department, and gaining in the community something of the honor which attends successful work.

A strict system of accountability has been maintained, step by step, from the lowest to the highest executive officer. Of many engaged in the labors of this Association, it can be truly said, that no business or commercial house was ever more faithfully and earnestly served, than this charity has been by them. Indeed, some of them have poured forth for it more vitality and energy than they would ever have done for their personal interests. They have toiled day and night, week-days and Sundays, and have been best rewarded by the fruit they have beheld. The aim of the writer, as executive officer, has been to select just the right man for his place, and to make him feel that that is his profession and life-calling. Amid many hundreds thus selected, during twenty years, he can recall but two or three mistaken choices, while many have become almost identified with their labors and position, and have accomplished good not to be measured. His principle has been to show the utmost respect and confidence, but to hold to the strictest accountability. Not a single employe, so far as he is aware, in all this time, during his service, has ever wronged the Society or betrayed his trust. One million of dollars has passed through the hands of the officers of this Association during this period, and it has been publicly testified [See testimony before the Committee on Charities of the Senate of New York, 1871.] by the Treasurer, Mr. J. E. Williams, President of the Metropolitan Bank, that not a dollar, to his knowledge, has ever been misappropriated or squandered.