полная версия

полная версияPrisoners of Poverty: Women Wage-Workers, Their Trades and Their Lives

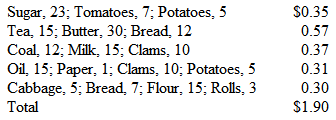

“It might have been better to go to the country,” she said. “But you see I wasn’t used to the country, and then any work I could get to do was right here. I’d always liked to sew, and so had Emeline, and we found we could get regular work on children’s suits, with skirts and such things in the dull seasons. It was good pay, and we were comfortable till prices began to fall. We made fifteen dollars a week sometimes, and could have got ahead if it hadn’t been for a little debt of my husband’s that I wanted to pay, for we’d never owed anybody a penny and I couldn’t let even that debt stand against his name. But when it was paid, somehow I came down with rheumatic fever, and I’ve never got back my full strength yet. And the prices kept going down. Emmy is an expert. I never knew her make a mistake, but working twelve and fourteen hours a day, – and it’s ’most often fourteen, – the most she has made for more than a year and a half is eighty-five cents a day, and on that we’ve managed. I suppose we couldn’t if I ever went out, but I’ve had no shoes in two years. I patch the ones I got then with one of my husband’s old coats, and keep along, but we never get ahead enough for me to have shoes, and Emmy too, and she’s the one that has to go out. How we live? It’s all in this little book. It’s foolish to put it down, and yet I always somehow liked to see how the money went, even when I had plenty, and it’s second nature to put down every cent. Take last month. It had twenty-seven working days: $22.95. Out of that we took first the ten dollars for rent. I’ve been here eleven years, and they’ve raised a dollar on me twice. That leaves $12.95 for provisions and coal and light and clothes. ’Tisn’t much for two people, is it? You wouldn’t think it could be done, would you? Well, it is, and here’s the expense for one week for what we eat: —

“This week was an expensive one, for I got a pound of butter at once, but it will last into next week. And we had to have the scissors sharpened; that was five cents. There would have been five cents for wood, but you see they’re building down the street, and one of the boys upstairs brought me a basketful of bits. You see there’s no meat. We like it, but we only get a bit for Sundays sometimes. Emmy never wants much. Running a machine all day seems to take your appetite. But she likes clams; you see we had them twice, and I happened to read in the paper a good while ago that you could make soup of the water the cabbage was boiled in; a quart of the water and a cup of milk and a bit of butter and some flour to thicken. You wouldn’t think it could be good, but it is, and it goes a good way. The coal ought not to be in with the food, ought it, unless it stays because I have to use it cooking? We oughtn’t to spend so much on food, but I can’t seem to make it less. Really, when you take out the coal and oil and the paper, – and we do want to see a paper sometimes, – it’s only 1.62 for us both; eighty-one cents apiece; almost twelve cents a day, but I can’t well seem to make it less. I call it twelve cents a day apiece. For the month that makes $7.44, and so you see there’s $5.51 left. Then there are Emmy’s car-fares when she goes out, for sometimes she works down-town and only evenings at home. Last month it was sixty cents a week, $2.70 for the month, and so there was just $2.81 left, and $1.50 of that went for shoes for Emmy. The month before, my hands weren’t so stiff and I helped her a good deal, so we earned $26.70, and she got two remnants for $1.80 at Ehrich’s and I made her a dress that looks very well. But she’s nothing but patchwork underneath, and I’m the same, only worse. The coal is the trouble. By the scuttle it costs so much, and I try to get ahead and have a quarter of a ton at once, for there are places here to keep coal, but I never can. If it weren’t for Emmy’s missing me, it would be better for me to die, for I’m no use, you see, and times get no better, but worse. But I can’t, and we must get along somehow. Lord help us all!”

“How could twelve cents’ worth of coal do a week’s cooking?”

“It couldn’t. It didn’t. I’ve a little oil stove that just boils the kettle, and tea and bread and butter what we have mostly. A gallon of oil goes a long way, and I can cook small things over it, too. The washing takes coal, and you see I must have soap and all that. I don’t see how we could spend less. I’ve learned to manage even with what we get now, but there’s a woman next door that I know better than anybody in this house, – for here it always seemed to me best to keep quite to myself for many reasons, but the chief that I’m always hoping for a change and a chance for Emmy. But this woman is a nice German woman that fell on the ice and sprained her ankle last winter, and we saw to her well as we could till she got better. She won’t mind telling how she manages, but she’s in the top of the house. She’s a widow, and everybody dead belonging to her.”

This house was a grade below the last in cleanliness, and children swarmed on stairs and in hall. Up to the fourth floor back; a ten-feet-square room, with one window, where, in spite of a defective sink in the hall, the odor from which seemed to penetrate and saturate everything, spotless cleanliness was the expression of every inch of space.

“Vy not?” the old woman said, when she understood my desire. “I tells you mine an’ more, too, for down de stairs I buy every day for the girl that is sick and goes out no more. If I quick were as girl I could save much, but I have sixty-five year. How shall I be quick? I earn forty-five, fifty cents sometime, but forty-five for day’s work when I go as I can. An’ so for week dat is $2.70; I can ten dollars a month, sometimes twelve dollars, and I pays three dollars for this room. To eat I will buy tea and our bread, – rye, for dat is stronger as your fine wheat. Tea is American, but I will not beer any more, since I see how women drinks it and de kinder, and it not like our beer but more tipsy. So I makes tea, and de cheese and de wurst is all not so much. It is de coal that is most. Vat I vill eat, he cost not so more as fifty cent; sometimes sixty, but I eat not ever all I could, for I must be warm a little, and dere is light, and to wash, and some shoe. It is bad to be big as I, for shoe not last. But a loaf of bread, five cents, do all day and some in next; and cheese a pound is ten, if I have him; and wurst is fifteen, for sometime he is best, and a pound stay a week if I not greedy. Tea will be thirty cents, but he is good a month, and sugar a pound, two pound sometime, but butter no, and milk a cent for Sunday. So I live, and I beg not. Can I more? I thank the good God only that there is no more Hans or Lisa or any to be hungry with me. It is good they go.”

“And you buy for some one else?”

“Oh ja, but she will die soon and care not. It is de kinder that care. Two, and one six and one eight and cannot earn. She sew all day on machine. It is babies’ cloaks, so vite and nice. In two days she will make dree, for see, dere is two linings and cape and cuff is all scallop, and she must stitch first and then bind and hem. All is hem, all over inside, so nice, and she make dem so nice. But eight dollars a dozen is all, and it is a week for nine, and so she get not more as five dollars because she is sick and must stop. And there is the grandvater that is old, and de kinder and she and all must live. Rent is $5.50, dat I know, and I pay for her dis week $1.60 for bread and tea and potatoes and some milk, and molasses for de kinder on bread, and butter a little, and milk, but not meat. It is de grandvater eat too much, but how shall one help it? De rest is clothes for all, but dere is no shoe for de kinder, and I see not if dere will be shoe. How shall it be?”

One after another the cases on the west side gave in their testimony. Save in the first one there were no formal accounts. But a little thinking brought out the items, – for many baker’s bread, tea, sugar, a little milk, and butter and a bit of meat once or twice a week, the average cost of food per head for the majority of cases being ninety cents per week. All coal was bought by the scuttle, a scuttle of medium size counting as twelve cents’ worth, thus much more than doubling the cost per ton. In the same way, wood by the bundle and oil by the quart gave the utmost margin of profit to the seller, and the same fact applied to all provisions sold. In no case save the one first mentioned, where the mother had learned that cabbage-water can form the basis for a nourishing and very palatable soup, was there the faintest gleam of understanding that the same amount of money could furnish a more varied, more savory, and more nourishing regimen.

“Beans!” said one indignant soul. “What time have I to think of beans, or what money to buy coal to cook ’em? What you’d want if you sat over a machine fourteen hours a day would be tea like lye to put a back-bone in you. That’s why we have tea always in the pot, and it don’t make much odds what’s with it. A slice of bread is about all. Once in a while you get ragin’, tearin’ hungry. Seems as if you’d swallow teapot or anything handy to fill up like, but that ain’t often – lucky for us!”

“If you all clubbed together, couldn’t one cook for you, – make good soup and oatmeal and things that are nourishing? You would be stronger then.”

“Stronger for what? More hours at the machine? More grinding your own flesh and bones into flour for them that’s over us? Ma’am, it’s easy to see you mean well, an’ I won’t say but what you know more than some that comes around what you’re talkin’ about. Club we might. I’m not denying it could be done, if there was time; but who of us has the time even if she’d the will? I was never much hand for cookin’. We’d our tea an’ bread an’ a good bit of fried beef or pork, maybe, when my husband was alive an’ at work. He cared naught for fancy things like beans an’ such. It’s the tea that keeps you up, an’ as long as I can get that I’ll not bother about beans.”

In the same house an old Swiss woman, who had fallen from her first estate as lady’s maid through one grade and another of service, was ending her days on a wage of two dollars per week, earned in a suspender factory, where she sewed on buckles. In her case marriage with a drinking husband had eaten up both her savings and her earnings, and age now prevented her taking up household service, which she ranked as most comfortable and most profitable. But she had been taught while almost a child to cook, and though her expenditure for food was a little below a dollar per week, the savory smell from a saucepan on her tiny stove showed that she had something more nearly like nourishment than her neighbors.

“I try sometimes to teach,” she said. “I give some of my soup, and they eat it and say it is good, but they not stop to do so much dat is fuss. All this in the saucepan is seven cents, – three cents for bones and some bits the kind butcher trow in, and the rest vegetable and barley. But it makes me two days. I have lentils, too, yes, and beans, and plenty things to flavor, and I buy rye bread and coffee to Sunday. Never tea, oh, no! Tea is so vicket. It make hand shake and head fly all round. Good soup is best, and more when one can. Vegetable is many and salad, and when I make more dollar I buy some egg. But not tea; not big loaf of white bread dot swell and swell inside and ven it is gone leave one all so empty. I would teach many but they like it not. They want only de tea; always de tea.”

“De tea” and the sewing-machine are naturally inseparable allies, and so long as the sewing-women must work fourteen hours daily they will remain so; the rank fluid retarding digestion and thus proving as friendly an aid as the “bone” which the half-fed Irish peasant demands in his potato. For the west side the story was quite plain, but for such returns as the east side has to offer there is still room for further detail.

CHAPTER ELEVENTH.

UNDER THE BRIDGE AND BEYOND

Between east and west side poverty and its surroundings exists always this difference, that the west is newer and thus escapes the inherited miseries that hedge about life in such regions as the Fourth Ward. There, where old New York once centred, and where Dutch gables and dormer windows may still be seen, is not only the foulness of the present, each nationality in the swarming tenements representing a distinct type of dirt and a distinct method of dealing with it and in it, but the foulness also of the past, in decay and mould and crumbling wall and all silent forces of destruction at work here for a generation and more. Those of us who have watched the evolution of the Fourth Ward into some show of decency recognize many causes as having worked toward the same end; yet even when one notes to-day the changes wrought, first by business, the march of which has wiped out many former landmarks, setting in their place great warehouses and factories, and then of philanthropy, which, as in the case of Miss Collins’s tenements, has transformed dens into some semblance of homes, there remains the conviction that dens are uppermost still. The business man hurrying down Fulton or Beekman Street, the myriads who pass up and down in the various east-side car lines, with those other myriads who cross the great Bridge, have small conception what thousands are packed away in the great tenements, and the rookeries even more crowded, or what depth of vileness flaunts itself openly when day is done and the creatures of shadow come out to the light that for many quarters is the only sunshine. This ward has had minute and faithful description from one of the most energetic of workers for better sanitary conditions among the poor, – Mr. Charles Wingate, whose admirable papers on “Tenement House Life,” published by the “Tribune” in 1884-1885, must be regarded as authority for the sanitary phases of the question. Little by little these have bettered, till the death rate has come within normal limits and the percentage of crime ceased to represent the largest portion of the inhabitants. Yet here, on this familiar battle-ground, civilization and something worse than mere barbarism still struggle. For which is the victory?

Under the great Bridge, whose piers have taken the place of much that was foulest in the Fourth Ward, stands a tenement-house so shadowed by the structure that, save at midday, natural light barely penetrates it. The inhabitants are of all grades and all nationalities. The men are chiefly ’longshoremen, working intermittently on the wharves, varying this occupation by long seasons of drinking, during which every pawnable article vanishes, to be gradually redeemed or altogether lost, according to the energy with which work is resumed. The women scrub offices, peddle fruit or small office necessities, take in washing, share, many of them, in the drinking bouts, and are, as a whole, content with brutishness, only vaguely conscious of a wretchedness that, so long as it is intermittent, is no spur to reform of methods. The same roof covers many who yield to none of these temptations, but are working patiently; some of them widows with children that must be fed; a few solitary, but banding with neighbors in cloak or pantaloon making, or the many forms of slop-work in the hands of sweaters. Sunshine has no place in these rooms which no enforced laws have made decent, and where occasional individual effort has power against the unspeakable filth ruling in tangible and intangible forms, sink and sewer and closet uniting in a common and all-pervading stench. The chance visitor has sometimes to rush to the outer air, deadly sick and faint at even a breath of this noisomeness. The most determined one feels inclined to burn every garment worn during such quest, and wonders if Abana or Pharpar or even Jordan itself could carry healing and cleansing in their floods.

The dark halls have other uses than as receptacles for refuse or filth. Hiding behind doors or in corners, or, grown bolder, seeking no concealment, children hardly more than babies teach one another such new facts of foulness as may so far have chanced to escape them, – baby voices reciting a ritual of oaths and obscenity learned in this Inferno, which, could it have place by Dante’s, might be better known to a cultured generation. Only a Zola could describe deliberately what any eye may see, but any minute detail of which would excite an outburst of popular indignation. Yet I am by no means certain that such detail has not far more right to space than much that fills our morning papers, and that the plain bald statement of facts, shorn of all flights of fancy or play of facetiousness, might not rouse the public to some sense of what lies below the surface of this fair-seeming civilization of to-day. Not alone in the shadow of the great pier, but wherever men and women must herd like brutes, these things exist and shape the little lives that missions do not, and as yet cannot, reach, and that we prefer to deal with later, when actual violation of laws has placed them in the hands of the State. Work as she may, the woman who must find home for herself and children in such surroundings is powerless to protect them from the all-pervading foulness. They may escape a portion of the actual degradation. They can never escape a knowledge the possibility of which is unknown to what we call barbarism, but part and parcel of the daily life of civilization.

Granted instantly that only the lowest order of worker must submit to such conditions, yet we have seen that this lowest order is legion; that its numbers increase with every day; and that no Board of Health or of Sanitary Inspectors has yet been able to alter, save here and there, the facts that are a portion of the tenement-house system.

It is chiefly with the house under the Bridge that we deal at present. Its upper rooms hold many workers whose testimony has helped to make plain how the east side lives. Little by little, as the blocks of granite swung into place and the pier grew, the sunshine vanished, its warmth and light replaced by the electric glow, cold and hard and blinding. The day’s work has ceased to be the day’s work, and the women who cannot afford the gas or oil that must burn if they work in the daytime, sleep while day lasts, and when night comes and the electric light penetrates every corner of the shadowy rooms, turn to the toil by which their bread is won. Never was deeper satire upon the civilization of which we boast. Natural law, natural living, abolished once for all, and this light that blinds but holds no cheer shining upon the mass of weary humanity who have forgotten what sunshine may mean and who know no joy that life was meant to hold!

In one of these rooms, clean, if cleanliness were possible where walls and ceiling and every plank and beam reek with the foulness from sewer and closet, three women were at work on overalls. Two machines were placed directly under the windows to obtain every ray of light. The room, ten by twelve feet, with a small one half the size opening from it, held a small stove, the inevitable teapot steaming at the back; a table with cups and saucers and a loaf of bread still uncut; and a small dresser in one corner, in which a few dishes were ranged. A sickly geranium grew in an old tomato-can, but save for this the room held no faintest attempt at adornment of any sort. In many of them the cheapest colored prints are pinned up, and in one, one side had been decorated with all the trademarks peeled from the goods on which the family worked. Here there was no time for even such attempts at betterment. The machines rushed on as we talked, with only a momentary pause as interest deepened, and one woman nodded confirmation to the statement of another.

“We’ve clubbed, so’s to get ahead a little,” said the finisher, whose fingers flew as she made buttonholes in the waistband and flap of the overalls. “We were each in a room by ourselves, but after the fever, when the children died and I hadn’t but two left, it seemed as if we’d be more sensible to all go in together and see if we couldn’t be more comfortable. We’d have left anyway, and tried for a better place, but for one thing, – we hadn’t time to move; and for another, queer as it seems, you get used to even the worst places and feel as if you couldn’t change. We’ll have to, if the landlord doesn’t do something about the closets. It’s no good telling the agent, and I don’t know as anybody in the house knows just who the landlord is. Anyway, the smell’s enough to kill you sometimes, and it’s a burning disgrace that human beings have to live in such a pig-pen. It’s cheap rent. We pay five dollars a month for this place. When I came here it was from a neck-tie place over on Allen Street, that’s moved now, and my husband was mate on a tug and earned well. But he took to drink and sold off everything I’d brought with me, and at last he was hurt in a fight round the corner, and died in hospital of gangrene. Mary’s husband there was a bricklayer and had big wages, but he drank them fast as he made them, and he was ugly when the drink was in, which mine wasn’t. But there’s hardly one in this house, man or woman, that don’t take a drop to keep off the fever; and even I, that hate the sight or smell of it, I wake up in the morning with an awful kind o’ goneness that seems as if a taste might help it. The tea stops that, though. Tea’s the best friend we’ve got. We’d never stand it if it wasn’t for tea.”

“Are overalls steady pay through the year?”

“There’s nothing that’s steady, so far as I can find out, but want and misery. Just now overalls are up; the Lord only knows why, for you never can tell what’ll be up and what down. They’re up, and we’re making a dollar a dozen on these. I have done a dozen a day, but it’s generally ten. There’s the long seams, and the two pockets, and the buckle strap and the waistband and three buttonholes, and the stays and the finishing. They’re heavy machines too, and take the backbone right out of you before night comes. But you sleep like the dead, that’s one comfort. It would be more if you didn’t have to wake more than they do. When the overall rush is over, it’ll be back to pants again. That’s my trade. I learned it regular after I was married, when I saw Tim wasn’t going to be any dependence. There were the children then, and I thought I’d send ’em to school and keep things decent maybe. I know all about pants, the best and the worst, but it’s mostly worse these days. First the German women piled in ready to do your work for half your rates, and when they’d got well started, in comes the Italians and cuts under, till it’s a wonder anybody keeps soul and body together.”

“We don’t,” one of the women said, turning suddenly. “I got rid o’ my soul long ago, such as ’twas. Who’s got time to think about souls, grinding away here fourteen hours a day to turn out contract goods? ’Tain’t souls that count. It’s bodies that can be driven, an’ half starved an’ driven still, till they drop in their tracks. I’m driving now to pay a doctor’s bill for my three that went with the fever. Before that I was driving to put food into their mouths. I never owed a cent to no man. I’ve been honest and paid as I went and done a good turn when I could. If I’d chosen the other thing while I’d a pretty face of my own I’d a had ease and comfort and a quick death. Such life as this isn’t living.”

The machine whirled on as she ended, to make up the time lost in her outburst. The finisher shook her head as she looked at her, then poured a cup of tea and put it silently on the edge of the table where it could be reached.

“She’s right enough,” she said, “but there’s no use thinking about it. I try to sometimes, just to see if there’s any way out, but there isn’t. I’ve even said I’d take a place; but I don’t know anything about housework, and who’d take one looking as I do, and not a rag that’s fit to be put on? I cover up in an old waterproof when I go for work. They wouldn’t give it to me if they saw my dress in rags below, and me with no time to mend it. But we’re doing better than some. We’ve had meat twice this week, and we’ve kept warm. It’s the coal that eats up your money, – twelve cents a scuttle, and no place to keep more if ever we got ahead enough to get more at a time. It’s lucky that tea’s so staying. Give me plenty of tea, and the most I want generally besides is bread and a scrape of butter. It’s all figured out. It’s long since I’ve spent more than seventy-five cents a week for what I must eat. I’ve no time to cook even if I had anything, so it’s lucky I haven’t. I suppose there’d be plenty to eat if you once made up your mind to take a place.”