полная версия

полная версияLife of Mary Queen of Scots, Volume 2 (of 2)

To this epistle Lord Herries made the following spirited reply:

“Lord Lindsay, – I have seen a writing of yours, the 22d of December, and thereby understand, – ‘You are informed that I have said and affirmed, that the Earl of Murray, whom you call your Regent, and his company, are guilty of the Queen’s husband’s slaughter, father to our Prince; and if I said it, I have lied in my throat, which you will maintain against me as becomes you of honour and duty.’ In respect they have accused the Queen’s Majesty, mine and your native Sovereign, of that foul crime, far from the duty that good subjects owed, or ever have been seen to have done to their native Sovereign, – I have said – ‘There is of that company present with the Earl of Murray, guilty of that abominable treason, in the fore-knowledge and consent thereto.’ That you were privy to it, Lord Lindsay, I know not; and if you will say that I have specially spoken of you, you lie in your throat; and that I will defend as of my honour and duty becomes me. But let any of the principal that is of them subscribe the like writing you have sent to me, and I shall point them forth, and fight with some of the traitors therein; for meetest it is that traitors should pay for their own treason. Herries. London, 22d of December 1568.”

No answer appears to have been returned to this letter, and so the affair was dropped. – Goodall, vol. ii. p. 271.

174

Goodall, vol. ii. p. 313.

175

Chalmers, vol. i. p. 327.

176

Chalmers, vol. i. p. 332.

177

Anderson, vol. i. p. 80.

178

Strype, vol. i. p. 538. – Chalmers, vol. i. p. 337.

179

Stranguage, p. 114.

180

Goodall, vol. ii. p. 375. – Anderson, vol. ii. p. 261. – Stuart, vol. ii. p. 59. – Chalmers, vol. i. p. 349.

181

Anderson, vol. iii. p. 248.

182

See “An Account of the Life and Actions of the Reverend Father in God, John Lesley, Bishop of Ross,” in Anderson, vol. iii. p. vii.

183

Miss Benger, vol. ii. p. 439.

184

Additions to the Memoirs of Castelnau, p. 589, et seq.

185

Laing, vol. ii. p. 285.

Alas! what am I? – what avails my life?Does not my body live without a soul? —A shadow vain – the sport of anxious strife,That wishes but to die, and end the whole.Why should harsh enmity pursue me more?The false world’s greatness has no charms for me;Soon will the struggle and the grief be o’er; —Soon the oppressor gain the victory.Ye friends! to whose remembrance I am dear,No strength to aid you, or your cause, have I;Cease then to shed the unavailing tear, —I have not feared to live, nor dread to die;Perchance the pain that I have suffered here,May win me more of bliss thro’ God’s eternal year.186

See the whole of this letter in Whittaker, vol. iv. p. 399. Camden translated it into Latin, and introduced it into his History; but he published only an abridged edition of it, which Dr Stuart has paraphrased and abridged still further; and Mademoiselle de Keralio has translated Dr Stuart’s paraphrased abridgment into French, supposing it to have been the original letter. Stuart, vol. ii. p. 164. – Keralio, Histoire d’Elisabethe, vol. v. p. 349.

187

Chalmers, vol. i. p. 395.

188

They were hanged on two successive days, seven on each day; and the first seven, among whom were Ballard, Babington, and Savage, were cut down before they were dead, embowelled, and then quartered. —Stranguage, p. 177.

189

Stranguage, p. 176. – Chalmers, vol. i. p. 427 et seq.

190

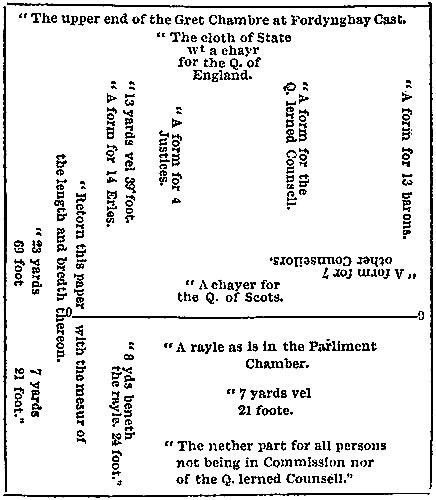

In the first series of Ellis’s Collection of “Original Letters illustrative of English History,” there is given a fac simile of the plan, in Lord Burleigh’s hand, for the arrangement to be observed at the trial of the Queen of Scots. As it is interesting, and brings the whole scene more vividly before us, the following explanatory copy of it will be perused with interest.

Below, in another hand, apparently in answer to Lord Burleigh’s direction, is the following:

“This will be most convenientlye in the greatt Chamber; the lengthe whereof is in all xxiij. yerds with the windowe: whereof there may be fr. the neither part beneth the barre viij. yerds: and the rest for the upper parte. The breadeth of the chamber is vij. yerds.

“There is another chambre for the Lords to dyne in, the lengthe is xiiij. yerds; the breadeth, vij. yerdes; and the deppeth iij. yerdes dim.”

191

As an example of some of the mistakes which the fabricators of these letters committed, it may be mentioned, that in one of them, dated the 27th of July 1586, Mary is made to say, – “I am not yet brought so low but that I am able to handle my cross-bow for killing a deer, and to gallop after the hounds on horseback, as this afternoon I intend to do, within the limits of this park, and could otherwhere if it were permitted.” Yet on the 3d of June previous, Sir Amias Paulet informed Walsingham – “The Scottish Queen is getting a little strength, and has been out in her coach, and is sometimes carried in a chair to one of the adjoining ponds to see the diversion of duck-hunting; but she is not able to walk without support on each side.” See Chalmers, vol. i. p. 426.

192

Camden, p. 519, et seq. – Stranguage, p. 192, et seq. – Robertson, Book VII. – Stuart, vol. ii. p. 268, et seq.

193

It deserves notice, that no particulars of the trial at Fotheringay have been recorded, either by Mary herself, or any of her friends, but are all derived from the narrative of two of Elizabeth’s notaries. If Mary’s triumph was so decided, even by their account, it may easily be conceived that it would have appeared still more complete, had it been described by less partial writers.

194

Camden, p. 525, et seq.

195

Murdin, p. 569.

196

Camden.

197

Jebb, vol. ii. p. 91.

198

Tytler, vol. ii. p. 319, et seq., and p. 403. – Chalmers, vol. i. p. 447. – Tytler gives a strong and just exposition of the shameful nature of the Queen’s correspondence with Paulet. The reader cannot fail to peruse the following passage with interest:

“The letters written by Elizabeth to Sir Amias Paulet, Queen Mary’s keeper in her prison at Fotheringay Castle, disclose to us the true sentiments of her heart, and her steady purpose to have Mary privately assassinated. Paulet, a rude but an honest man, had behaved with great insolence and harshness to Queen Mary, and treated her with the utmost disrespect. He approached her person without any ceremony, and usually came covered into her presence, of which she had complained to Queen Elizabeth. He was therefore thought a fit person for executing the above purpose. The following letter from Elizabeth displays a strong picture of her artifice and flattery, in order to raise his expectations to the highest pitch.

‘TO MY LOVING AMIAS‘Amias, my most faithful and careful servant, God reward thee treblefold for the most troublesome charge so well discharged. If you knew, my Amias, how kindly, beside most dutifully, my grateful heart accepts and praiseth your spotless endeavours and faithful actions, performed in so dangerous and crafty a charge, it would ease your travail, and rejoice your heart; in which I charge you to carry this most instant thought, that I cannot balance in any weight of my judgment the value that I prize you at, and suppose no treasure can countervail such a faith. And you shall condemn me in that fault that yet I never committed, if I reward not such desert; yea let me lack when I most need it, if I acknowledge not such a merit, non omnibus datum.’270

Having thus buoyed up his hopes and wishes, Walsingham, in his letters to Paulet and Drury, mentions the proposal in plain words to them. ‘We find, by a speech lately made by her Majesty, that she doth note in you both a lack of that care and zeal for her service, that she looketh for at your hands, in that you have not in all this time (of yourselves, without any other provocation) found out some way to shorten the life of the Scots Queen, considering the great peril she is hourly subject to, so long as the said Queen shall live.’ – In a Post-script: ‘I pray you, let both this and the enclosed be committed to the fire; as your answer shall be, after it has been communicated to her Majesty, for her satisfaction.’ In a subsequent letter: ‘I pray you let me know what you have done with my letters, because they are not fit to be kept, that I may satisfy her Majesty therein, who might otherwise take offence thereat.’

What a cruel snare is here laid for this faithful servant! He is tempted to commit a murder, and at the same time has orders from his Sovereign to destroy the warrant for doing it. He was too wise and too honourable to do either the one or the other. Had he fallen into the snare, we may guess, from the fate of Davidson, what would have been his. Paulet, in return, thus writes to Walsingham: – ‘Your letters of yesterday coming to my hand this day, I would not fail, according to your directions, to return my answer with all possible speed; which I shall deliver unto you with great grief and bitterness of mind, in that I am so unhappy, as living to see this unhappy day, in which I am required, by direction of my most gracious Sovereign, to do an act which God and the law forbiddeth. My goods and life are at her Majesty’s disposition, and I am ready to lose them the next morrow if it shall please her. But God forbid I should make so foul a shipwreck of my conscience, or leave so great a blot to my poor posterity, as shed blood without law or warrant.”

199

Mackenzie’s Lives of the Scottish Writers, vol. iii. p. 336. – Robertson, vol. ii. p. 194. – Chalmers, vol. i. p. 449.

200

La Mort de la Royne d’Ecosse in Jebb, vol. ii. p. 611.

201

Jebb, vol. ii. p. 622. et seq.

202

“Mary’s testament and letters,” says Ritson the antiquarian, “which I have seen, blotted with her tears in the Scotch College, Paris, will remain perpetual monuments of singular abilities, tenderness, and affection, – of a head and heart of which no other Queen in the world was probably ever possessed.”

203

Jebb, vol. ii. p. 628, et seq.

204

History of Fotheringay, p. 79.

205

Among these attendants were her physician Bourgoine, who afterwards wrote a long and circumstantial narrative of her death, and Jane Kennedy, formerly mentioned on the occasion of Mary’s escape from Loch-Leven.

206

Narratio Supplicii Mortis Mariae Stuart in Jebb, vol. ii. p. 163. – La Mort de la Royne d’Ecosse in Jebb, vol. ii. p. 636 and 639. – Camden, p. 535.

207

Jebb, vol. ii. p. 640, et seq.

208

See Mezeray, Histoire de France, tome iii.

209

“We may say of Mary, I believe, with strict propriety,” observes Whittaker, “what has been said of one of her Royal predecessors, – ‘the gracious Duncan,’ that she

“Had borne her faculties so meek, had beenSo clear in her great office, that her virtues,Will plead, like angels, trumpet-tongued, againstThe deep damnation of her taking off.”210

“Oraison Funebre” in Jebb, vol. ii. p. 671.

211

Anderson, vol. ii. p. 92.

212

Keith, p. 79.

213

Anderson, vol. i. p. 117. – Keith, p. 379.

214

Melville, p. 175. et seq.

215

Goodall, vol. ii. p. 90.

216

Keith, p. 406.

217

Anderson, vol. i. p. 139.

218

Keith, p. 417.

219

Haynes, p. 454. – Stuart, vol. i. p. 361.

220

Goodall, vol. ii. p. 66.

221

Keith, p. 467. – Anderson, vol. ii. p. 173.

222

Goodall, vol. ii. p. 140.

223

Goodall, vol. ii. p. 235.

224

Ibid. 256.

225

Tytler, vol. i. p. 144.

226

There is preserved at Hamilton Palace, a small silver box, said to be the very casket which once contained the Letters. Laing, who appears to believe in the genuineness of this relic somewhat too hastily, mentions, that “the casket was purchased from a Papist by the Marchioness of Douglas (a daughter of the Huntly family) about the period of the Restoration. After her death, her plate was sold to a goldsmith, from whom her daughter-in-law Anne, heiress and Dutchess of Hamilton, repurchased the casket.”

“For the following accurate and satisfactory account of the casket,” adds Mr Laing, “I am indebted to Mr Alexander Young, W. S., to whom I transmitted the description of it given in Morton’s receipt, and in the Memorandum prefixed to the Letters in Buchanan’s ‘Detection.’”

“‘The silver box is carefully preserved in the Charter-room at Hamilton Palace, and answers exactly the description you have given of it, both in size and general appearance. I examined the outside very minutely. On the first glance I was led to state, that it had none of those ornaments to which you allude, and, in particular, that it wanted the crowns, with the Italic letter F. Instead of these, I found on one of the sides the arms of the house of Hamilton, which seemed to have been engraved on a compartment, which had previously contained some other ornament. On the top of the lock, which is of curious workmanship, there is a large embossed crown with fleurs de lis, but without any letters. Upon the bottom, however, of the casket, there are two other small ornaments – one near each end, which, at first sight, I thought resembled our silver-smiths’ marks; but, on closer inspection, I found they consisted each of a royal crown above a fleur de lis, surmounting the Italic letter F.’” – Laing, vol. ii. p. 235.

Upon this description of the box, it may be remarked, that it does not exactly agree with the account given of it by Buchanan; for it would appear, that in the casket preserved at Hamilton, there are only two Italic F’s; while Buchanan describes it as “a small gilt coffer, not fully a foot long, being garnished in sundry places with the Roman letter F, under a king’s crown,” an expression he would not have used, had there been only two of these letters. Besides, there seems to have been a king’s crown above each; but on the coffer at Hamilton, there is only one crown on the top of the lock, and not above the letter F. Antiquarians, however, have investigated subjects of less curiosity, and have been willing to believe upon far more slender data.

227

Goodall, vol. ii. p. 87.

228

Goodall, vol. ii. p. 140.

229

Goodall, vol. ii. p. 235; and p. 257.

230

The authentic “Warrant” and “Consent,” has been already described, supra, vol. ii. p. 95, and may be seen at length in Anderson, vol. i. p. 87.

231

Laing, Appendix, vol. ii. p. 356.

232

See in further corroboration of the facts stated above, a Letter of Archibald Douglas to the Queen of Scots, in Robertson’s Appendix, or in Laing, vol. ii. p. 363.

233

“Nec ullam hac in causa reginæ accusationem intervenire.” – See the King of Denmark’s Letter in Laing, vol. ii. p. 328.

234

Goodall, vol. ii. p. 382.

235

Keith, Appendix, p. 141.

236

Jebb, vol. ii. p. 227. – Keith, Appendix, p. 143.

237

See the New Monthly Magazine, No. LIV. p. 521.

238

Lesley’s “Defence” in Anderson, vol. i. p. 40.

239

Miss Benger, Appendix, vol. ii. p. 494.

240

Buchanan, book xix. – Stuart, vol. i. p. 460.

241

Robertson, Appendix to vol. i. No. xxii.

242

Anderson, vol. iv. Part I. p. 120 and 125.

243

Keith, Appendix, p. 145.

244

Jebb, vol. ii. p. 671.

245

Anderson, vol. ii. p. 185.

246

Anderson, ibid. p. 187. – Laing, vol. ii. p. 296.

247

Laing, Appendix p. 323.

248

Laing, vol. ii. p. 298.

249

Ibid. p. 300.

250

Tytler, vol. i. p. 20.

251

It is unnecessary to enter into any discussion regarding the second Confession of Paris, which has been so satisfactorily proved to be spurious, by Tytler, Whittaker, and Chalmers, and on which Robertson acknowledges “no stress is to be laid,” on account of the “improbable circumstances” it contains. See Tytler, vol. i. p. 286. – Whittaker, vol. ii. p. 305. – Chalmers, vol. ii. p. 50. – Robertson, vol. iii. p. 20.

252

Robertson, vol. iii. p. 21.

253

Goodall, vol. ii. p. 371 and 375. – Robertson, vol. iii. p. 28.

254

The French edition of the Detection, p. 2. – Goodall, vol. i. p. 103.

255

Goodall, vol. ii. p. 235.

256

Laing, vol. i. p. 250.

257

See the Letter in Laing, vol. ii. p. 202; and an unsuccessful attempt to give a criminal interpretation to it, in vol. i. p. 311. It is quite unnecessary to allude here to several other flimsy forgeries which, at a later period, have been attempted to be palmed upon the world as genuine letters of Mary. In 1726, a book was published, entitled, “The genuine Letters of Mary Queen of Scots, to James Earl of Bothwell, found in his Secretary’s Closet after his Decease, and now in the Possession of a Gentleman at Oxford. Translated from the French by Edward Simmons, late of Christ-Church College, Oxford.” These had only to be read, to be seen to be fabrications. Yet so late as the year 1824, a compilation was published by Dr Hugh Campbell, containing, among other things, eleven letters, which the Doctor thought were original love-letters of the Queen to Bothwell, although, with a very trifling variation, they were the same as those published in 1726; only, not being described as translations, and being written in comparatively modern English, which Mary never could write, they bear still more evidently the stamp of forgery. This is put beyond a doubt, by a short Examination of them, published by Murray, London, 1825, and entitled, “A Detection of the Love-Letters, lately attributed, in Hugh Campbell’s Work, to Mary Queen of Scots; wherein his Plagiarisms are proved, and his fictions fixed.”

258

Whittaker, vol. ii. p. 79.

259

Goodall, vol. i. p. 79 – Laing, vol. i. p. 209.

260

Goodall, vol. ii. p. 342.

261

Jebb, vol. ii. 244.

262

Camden, p. 143. – Tytler, vol. i. p. 101.

263

Goodall, vol. ii. p. 31.

264

It is proper to state, that Robertson has considered this argument at some length; and though he has not overturned, he has certainly invalidated the strength of the evidence adduced by Goodall in support of it. – Goodall, vol. i. p. 118. – Whittaker, vol. i. p. 383. – Chalmers, vol. ii. p. 375. – Laing, vol. i. p. 315.

265

Whittaker, vol. i. p. 332.

266

Goodall, vol. ii. p. 64 & 67.

267

Whittaker, vol. i. p. 408.

268

Goodall, vol. ii. p. 51.

269

Regarding these sonnets, the curious reader may consult Whittaker, vol. iii. p. 55. – Stuart, vol. i. p. 395. – Jebb, vol. ii. p. 481 – and Laing, vol. i. p. 230. 347. 349. and 368. For remarks on the marriage-contracts, see Goodall, vol. ii. p. 54 & 56, and vol. i. p. 126. – Whittaker, vol. i, p. 392, and Stuart, vol, i. p. 397.

270

What a picture have we here, of the heroine of England! Wooing a faithful servant to commit a clandestine murder, which she herself durst not avow! The portrait of King John, in the same predicament, practising with Hubert to murder his nephew, then under his charge, shows how intimately the great Poet was acquainted with nature.

O my gentle Hubert,We owe thee much! Within this wall of flesh,There is a soul, counts thee her creditor,And with advantage means to pay thy love,And, my good friend, thy voluntary oathLives in this bosom dearly cherished.