полная версия

полная версияCheckers: A Hard-luck Story

"Poor Arthur!" sighed Sadie.

"Poor Pert," echoed Pert.

VI

The following afternoon Arthur complained of feeling ill. On the way home from the store he was taken with a violent chill, which was followed by a raging fever. The doctor was summoned, and pronounced it malaria, but typhoid symptoms developed later, and for weeks his life hung in the balance.

Meanwhile Checkers worked early and late at the store, to make up for Arthur's absence. He felt this loss of a companion keenly, and soon the long drive home alone, and the air of apprehension and lonesomeness, which pervaded the house, became so irksome to him that he arranged to stay in town with Mr. Bradley, who kept house with a maiden sister in their little home just next to the store.

It was from this same sister, who disliked Arthur, but had taken to Checkers, as every one did, that Pert at last learned the reason of Checkers coming to Clarksville.

Mr. Bradley had told his sister the bare facts as he had learned them from Arthur, and these she had enlarged upon in relating them to Pert, embellishing the story to suit her fancy.

The discovery of this attempt upon Arthur's part to shield himself, and belittle his friend, checked the growing pity and tenderness Pert felt for him because of his illness, and killed every possible vestige of regard she might have had remaining for him. Checkers, on the contrary, grew in favor. He had discovered that it was but a pleasant and picturesque walk from town to the Barlow place, and evening after evening found him seated under the trees with the girls, banjo in hand, singing for them, and telling them interesting tales of his many and varied experiences.

Sadie's father returned, and she went back to town to be with him. But Checkers still took his evening walk out the country road, except when Pert came in to spend the night with her cousin, as she often did.

Under such conditions friendships quickly ripen, and Checkers, at least, soon found himself upon the borderland of a warmer sentiment; but his manner continued one of purely good-natured interest and friendship, for, in spite of what Sadie had told him, he still felt that Pert belonged to Arthur.

One night he stayed somewhat later than usual. It had been dreadfully hot all day, but now it was gratefully cool. The stars were bright, as he had never seen them bright before; the scent of the magnolias was delicious, and he and Pert had been singing together. She looked more than sweet in her thin, white dress, and the night, the perfume and the music had stirred him strangely. He longed for the power to tell her in beautiful words, he knew not what. But he had the good sense to realize that he and poetry were far apart. Nevertheless, as he said good night, he held her small white hand in his, till she forcibly withdrew it, but not with any sign of anger.

How his heart swelled as he walked along. How he still thrilled with the gentle pressure he fancied he had felt returned. Here was the faintest opening to possibilities which might end, who could tell where? He had never before known a girl like this. In fact, with the one exception previously mentioned, girls had never in any way entered his life. Still he had learned in his fight with the world to look at everything from a practical standpoint, and he had not gone very far before his natural shrewdness asserted itself.

"It won't do, Campbell," he soliloquized, with an unconscious sigh. "You 're 'playing a dead one.' It's a hundred-to-one shot in the first place, and there is Arthur in the second. I wonder how he is to-day. I wonder if he's going to get well. If he shouldn't – but, my God, I hope he does – ain't it awful what thoughts will come to a fellow?

"I wonder if he 's got her 'nailed;' she does n't act much like it to me. But I do n't believe I 'm acting on the square to try to 'do' him when he ain't around to look after his trade. I 'll go up home to-morrow night and see the old man, if he 's able to sit up. I had my nerve with me to hold her hand – I wonder what she 'd have done if I 'd have kissed it? Gee! but it's tough to be on the tram," he continued with a sigh. "With a couple of thou. what could n't I do? But a man without money hasn't got 'openers;' he draws four to a queen and never betters."

He found Arthur convalescent and jealous of all the time that could be spared to him. So, much to Checkers' disgust, his only opportunity of now seeing Pert lay in her occasional visits to the store, when shopping, generally accompanied by Sadie.

As soon as Arthur was strong enough to be about the house, Aunt Deb, as a little surprise for him, asked Sadie and Pert to one o'clock Sunday dinner.

Arthur's hollow eyes beamed lovingly from his thin, pale face, as Pert entered the room. Checkers saw it, and his conscience smote him. "I 'll scratch my entry," he inwardly resolved, "and leave Arthur a walk-over."

The afternoon passed uneventfully. The day was warm, the sun shone bright, and they all sat under the shade of the trees, enjoying the air and the beautiful view of the mountains, now made gorgeous by the brilliant and variegated colors of the changing autumn leaves.

Pert so managed that she was not left alone with Arthur at any time, and she and Sadie left somewhat early in order to reach home well before dark.

After their departure Checkers and Arthur sat together in the hammock. Arthur was monosyllabic. Checkers talked for a while against time, but not with any brilliant success. "Come, 'smoke up,' old man – you 're going out!" he exclaimed, slapping Arthur on the back, a figure doubtless suggested to him by the dying cigarette-stump between his fingers.

"I wish to heaven I had 'gone out;' instead of getting well," was the answer; "I am no good to myself, nor to any one else, and the only being in the world I love, except my father, cares no more for me than she does for a yellow dog."

There was an embarrassing silence.

"Girls are funny," said Checkers, musingly.

Arthur saw no grounds for argument, and Checkers continued, "I never had much time for them, myself, but my friend 'Push' Miller had them coming his way in carriages. You never saw such a fellow for girls; he always had three or four on his staff. He used to play a system on them. I think he called it the Fabian System, after some old joker in the war, who used to win his battles by running away. You see, the other guys would come chasing after this joker, and when he got them where he wanted, he 'd go out and nail them – easy thing.

"Well, this Fabian System was a dead sure winner for Push, and if I were you, I 'd try it. The next time you get together, 'jolly up' Sadie. Don't push it too strong; but just enough so that Pert will notice it – she'll get jealous. 'Jolly' Sadie harder, but be polite to Pert, and pretty soon you 'll have her guessing. The chances are that before long she 'll make a play at you – give her the frozen face. Put up a talk about how much you used to love her; work in something about the past, and what might have been. But keep a little up your sleeve; you do n't want her to think you 're coming too easy, and after things are all fixed up, do n't treat her too well again. Push used to say 'there was nothing that really spoiled a girl like treating her too well.' He used to make a date every once in a while, and then break it without sending any excuse, just to show the girl that he was 'good people,' and teach her to have a proper respect for him."

Arthur smiled wearily. "Yes;" he said, "that may have done all very well for Push, but it would n't do for me. The girl does n't love me, and there's the end of it. Perhaps some day – well, there's no use discussing it; besides, it would n't be fair to Sadie to use her merely as a cat's-paw. She is a true little girl, with a big, warm heart, and I would n't deceive her for the world."

"Well, what's the matter with going out after Sadie in earnest, then?" said Checkers. "Now there 's a scheme that fixes things up all around." Checkers waxed enthusiastic.

Arthur did not reply immediately. "Sadie is an earnest, capable girl," he said at length, "and she 'll make some man a splendid wife. I would cheerfully recommend her to my very best friend, but – "

"But your friend could have her without a struggle," suggested Checkers; and then they both laughed.

This, Checkers afterwards told me was the nearest approach to a joke he ever heard Arthur make.

A week passed by uneventfully. Arthur continued to improve in health. Checkers drove home each evening tired from his hard day's work. Saturday night a note from Pert arrived, inviting them both to dinner on the following day; a return of courtesies which they accepted with pleasure.

Sadie drove up that morning to spend a day or two with her cousin. The dinner passed off pleasantly, and in the afternoon the four took a stroll through the neighboring woods, to a beautiful spot where from the top of a cliff of massive rock they could gaze for miles up the dark, thickly wooded ravine, lying sheer many feet below.

Sadie and Arthur walked off together. Checkers and Pert followed leisurely.

"Do you think you deserve to be treated so well, after neglecting me as you have lately?" asked Pert.

"I have n't been able to get here, Miss Pert," replied Checkers. "The Broadway cable isn't in it with the way I've been pulling to get away; but if Arthur had known I was coming here, we would only have had a speaking acquaintance. I'll tell you, Miss Pert, that poor boy is all broke up about you, and to come down to cases, it ain't very safe for me to be seeing so much of you, when – well, you know he saw you first, and the rights of property – "

"Now, listen to me," interrupted Pert, with a stamp of her foot, "Arthur is nothing to me; I do n't love him and I shall never marry him. I 've told him so, and I 'll tell you so. I 've enjoyed having you call here very much, and there 's no reason why you shouldn't come – unless, of course, you would rather not."

Ahead, Arthur was carefully helping Sadie over a fallen tree which lay across the path. "He 's playing the system, after all," thought Checkers, "I'll help him push it along. May I come to-morrow night?" he said; "it's the first night I 've got disengaged."

"Certainly," laughed Pert. "Sadie is going to stay until Tuesday morning, and – "

"Make it Tuesday night."

Pert assented with an audible chuckle.

And now they had come to the fallen tree, an ancient pine of huge dimensions. Checkers clambered atop of it, and, taking both of Perl's hands, pulled her up; then, from the other side, he supported her tenderly as she jumped to the ground. 'Twas a rapturous moment. The fair, sweet face above him, and the bright, roguish eyes looking down into his; the warm, red lips, half parted in a smile, and coming so near as he carefully lowered her, tempted him sorely. But he resisted; not from any strength of virtue, but because he did not dare to do otherwise.

"Thank you," said Pert. Checkers was silent. His emotions of mingled excitement and regret were such that he could not trust his voice; but as they drew near to where Arthur and Sadie were sitting, he purposely drew away from Pert, and feigned a look of general indifference, which was masterly in its way.

"I may possibly stay down to-night, Arthur," called Checkers, as he drove out of the door-yard Tuesday morning.

Tuesday night found him seated with Pert in the cozy, old-fashioned little sitting-room, before the blazing embers of a large, wood fire, for it had suddenly turned cold.

Checkers had brought up the illustrated papers, and with these and the banjo, with nuts and apples, pop-corn and cider, for refection, time sped merrily on.

Now, just how it all came about that night, Checkers never adequately explained to me. He always claimed, shamefacedly, to have a confused recollection of the matter. But suffice it to say, there came an opportunity, and, forgetting his former resolutions, forgetting his poverty – everything, he told as best he could the story of his love to the listening girl beside him. What matter how he told it? She cared not for that, so long as the tale rang true to her ears; and of Checkers' whole-hearted sincerity, there was never a doubt, as after events proved.

The strangeness of a woman's love has been a prolific source of wonder and remark for philosophers of every age. It should not, therefore, seem incongruous that Checkers, penniless, slangy, illiterate, should have won, in a few, short weeks, the love of a girl whom Arthur, a higher type, from a worldly standpoint, had tried for years to make his own, without success. Perhaps the explanation lay in the fact that Checkers possessed two qualities in which Arthur was wholly lacking – tact and magnetism; and again, Pert was too young and inexperienced to let worldly advantages weigh with her.

At all events, they sat there together, blissful in their new-found happiness, talking the love all lovers talk, and heedless of the speeding hours.

As Checkers rather coyly put it, "There was n't very much room in the room." The fire had died almost to ashes, and for the hundredth time he had said, "I must go," when suddenly he was jerked from his seat by a rough hand which had laid hold of his collar.

With a violent effort he broke away, and, turning about, faced Mr. Barlow.

"So!" snorted the old man, angrily, "so this is what ye 're doin', is it, settin' here philanderin'? I reckoned somethin' was goin' on. You go to yer room, girl; come, git along. And you, my young jack-snipe, mosey off afore I wear ye out with a switch."

Checkers' surprise had been so complete that for a moment he could not collect himself. Then such was his sense of anger at the indignity that had been put upon him that only Pert's hand upon his arm restrained him from making a fight of it. As it was, the two men stood with an armchair between them, grimly glaring at each other.

"Father," cried Pert, peeping timidly from behind Checkers, "Mr. Campbell and I are engaged to be married."

"To be what?" howled the old man, dancing with rage.

"To be married," said Checkers. "Now, listen to me, and don't you get so gay with yourself. I love your daughter; she loves me; we are going to be married, and that's the end of it."

Checkers stepped back. It was well that he did, for the old man suddenly reached for him, "and if he 'd have got me," said Checkers, afterwards, relating the incident to me, "he would n't have done a thing to me. We made a few laps around the room," he continued, "with the chairs and table in the middle. The old man ran a bang-up second, but he was 'carrying weight for age,' and I fouled him in the stretch, by pulling a rocker in the way, that he stumbled over; then, I opened the door, kissed Pert good by, grabbed my hat, and did the slide for the road. The old joker tried to 'sic' the dogs on me, but they knew me so well they would n't 'sic.'"

It had long been a pet scheme of Mr. Barlow's to marry Pert to Arthur Kendall. In fact, he considered the matter settled, and had often congratulated himself upon his prospects of securing a wealthy son-in-law. The presumption, therefore, of this "little pauper" drove him nearly beside himself.

Pert thought it wise to spend most of her time in her room next day, until the first burst of his anger should have subsided.

As Checkers drove home the following evening, he was met by Tobe, the hired man, about a mile from the house. "Hello, Tobe," he called, "what's up?"

"Thar's hell out, Mr. Checkers," said Tobe.

"Has old Barlow been up here?'

"He ain't gone two hours."

Checkers smiled. He was glad to know the worst. "I suppose I 'm not very popular with Arthur?"

"He swars he 'll fill ye full o' lead. I overheern the hull conversation atween 'em, and I 'lowed I 'd come down and warn ye. Mr. Kendall and Aunt Deb 's gone to Little Rock, and won't be back afore to-morrow night."

"Thank you, Tobe; get in and ride."

"Wal, till we gits in sight o' the house; but don't you 'low you 'd better go back?"

"No; I'll go on and face the music."

"Thar never was nawthin' but trouble come o' foolin' with women, anyhow," said Tobe. "I 've had four on 'em in my time, and they've worn the soul-case off'n me."

"Four!" exclaimed Checkers.

"Yes, I 've had four. My first woman spent me out o' house and home, and then run away – I was glad to get shet o' her. The second un I jest nachally could n't live with, she hed sech a pizen-bad temper; and I 've had two others to die on me. I 've worked like a nigger airnin' 'em money fer cloes, and doctor's bills and sich, and not one on 'em but what 'ud claim she wa'n't well treated. The trouble with women is that a man takes and treats 'em so well when he's a-courtin' of 'em, that after they 're married, plain, ordinary, every-day treatment seems like cruelty to 'em."

This was a phase of the woman question which had never before occurred to Checkers; but the weight of suspense at his heart prevented his encouraging Tobe to further reminiscence.

As he drove into the door-yard, Arthur came out of the house, trembling and pale with anger and excitement.

"Hello, Arthur?" called Checkers, cheerily.

"Traitor, hypocrite," was the answer; "how can you look me in the face?"

"Oh, get used to it."

"Ha! you make a jest of it, do you?"

"Of what, your face?"

Arthur grew livid. "It's easy and safe for you to taunt a man who is just recovering from a weakening sickness," he said. "If it were n't for my father, I 'd shoot you like the cur that you are, if I hanged for it."

Checkers jumped to the ground. "Now, look here, Arthur Kendall," he said threateningly. "I won't stand any such talk from any one. If you 're making your roar about Miss Barlow, and I suppose you are, I'll tell you this: The girl doesn't love you and never did, and why you should want to do the dog-in-the-manger act is more than I can see."

"No; of course she does n't love me, if a sneaking Judas goes and betrays me to her."

"I never mentioned your name to her, unless it was to say something good about you."

"You lie! You told her all about our affair at Hot Springs."

"I did no such thing."

"You did. She told her father about it, and he told me this very afternoon."

"Did he say I told her?"

"Who else could have told her? do you think I told her?"

"I do n't know, and, what's more, I don't care a damn. I do n't want any trouble with you, but I have n't got the temper of an angel, and I 'd advise you to take a tumble to yourself until I 'm gone – and that won't be longer than it takes me to get my stuff into my trunk."

"It can't be any too quick to suit me."

Checkers started for the house, but stopped half-way, and turned for a parting word, while Arthur stood still, and eyed him malignantly.

"Now, listen, Arthur Kendall," said Checkers earnestly; "and these are the last words I 'm going to say. I 've been on the square with you from the day I met you, and if our positions were reversed, I 'd take you by the hand and wish you all kinds of happiness, but as it is, you show the yellow streak I always thought you had in you – it's wider than I thought it was, that's all. But just keep saying this over to yourself: 'I love that girl and I 'm going to have her, in spite of her father, or you, or the world.'" And turning on his heel, Checkers went into the house to collect his few, poor, little belongings.

VII

That same night Pert, after another stormy interview with her father, had gone to her room, and, throwing herself on her little white bed, in a paroxysm of bitter grief, had softly sobbed herself to sleep.

Gradually into her dreams there came the whistled notes of a familiar little cadence, faint and far away at first, but growing louder and nearer until she awoke with a start.

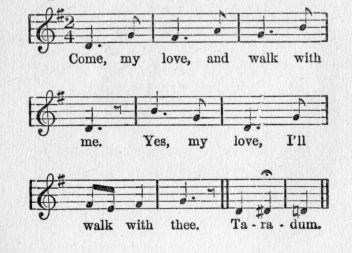

It was "a whistle" which Checkers had taught her weeks before, and ran as follows:

Come, my love, and walk with me.Yes, my love, I'll walk with thee.Ta-ra-dum.

At this time, however, Checkers, standing down in the road outside, had cut the "ta-ra-dum" as flippant and irrelevant – a delicacy which, in her trepidation, Pert failed to remark. But, jumping up, she lighted her lamp, and cautiously exposed it at the window for a moment. Then, thanking fortune that she chanced to be dressed, she slipped a warm wrap over her shoulders, and stole down the stairs, out into the night.

Checkers folded her in his arms, and kissed her gently. "My darling," he murmured, "you haven't let them turn you against me, have you?"

"Why, Checkers dear," she answered looking into his eyes, "the whole world could n't turn me against you – I love you." Checkers kissed her again.

In the bright starlight they sat together, once more on the little rustic bench under the tree, listening with ready sympathy, as each related to each the trials of the day.

"No, little sweetheart," said Checkers finally, "there is no possible way for me to stay in Clarksville. The old man is practically right, I am a pauper, but I won't be long. Pert, I can hustle, when I want to; I 've got enough money to take me to Chicago, and keep me till I can get a job. When I get to work I 'll salt every cent, and with any kind of luck, I 'll come back and get you within a year. A year is not such a very long while." And with a show of genuine enthusiasm, Checkers ended by talking the downcast girl into a happy confidence in himself and the future.

"And now, Pert," he said, solicitously, "it's too cold for you to stay out here longer; come, we must be brave, and say good-bye."

"O, Checkers," she exclaimed, with a choking sob, suddenly throwing her arms around his neck, "I can't bear to let you go; I shall be miserable, miserable without you."

Tenderly Checkers soothed and reasoned with her. Once more their plans were gone over. Checkers was to leave in the morning for Chicago. He was to write to her as often as possible, addressing the letters to Sadie, whom Pert knew she could depend upon. Checkers was to bend every effort towards getting a position and saving money; and Pert was to be brave, and wait – the common lot of women.

With his arm around her, lovingly, he led her slowly to the house. Again and again they said good-bye; but there is something in the word which makes us linger.

"Some little keepsake, sweetheart," he whispered – "this ribbon, or your handkerchief."

"No; wait here a minute," she answered. Carefully entering the house, she crept to her room, and from its hiding-place brought forth a fifty-dollar gold piece. It was of California gold, octagonal in shape, and minted many years before.

"Here, dear," she said, returning noiselessly. "Here is a coin that was given me long ago by my grandfather – take it as a lucky-piece. And whenever you see it, think of one who loves you and is praying for you. And, Checkers, if you should have misfortune, and should really need to, don't hesitate to spend it; because, you see, if you don't have good luck, so that you do n't need to spend it, why it is n't a lucky piece, and you 'd better get rid of it – that is, if – if you have to."

Checkers embraced her passionately. "My darling," he protested, "I shall have to be nearer starving to death than I 've ever been, or expect to be, before I part with this. I shall treasure it as a keepsake from the dearest, sweetest, prettiest, sandiest girl in the world; the one that I love and the one that loves me; and here – here's a scarfpin that once was my father's. They say opals are unlucky. Well, father got shot, but I wore it the lucky day I met you; so that does n't prove anything – wear it for my sake. Now, dear, I must go. Keep a stiff upper lip, and do n't let the old man get in his bluff on you. Win your mother over – she'll help you out. I think she likes me; I am sure I do her. I 'll write to you every day. Good-bye, my precious – I 'll be back for you soon; good-bye, good-bye."

One last fond embrace, one lingering kiss, and Checkers turned and walked resolutely away.

The next morning early he bid the Bradleys a sorrowful farewell, and boarded the train for Little Rock. Mr. Bradley gave him letters to a number of merchants there, but he was unable to find employment. In fact, he only sought it in a half-hearted way; Little Rock was too small, too near Clarksville. Chicago was his Mecca. He felt a happy presentiment that once there circumstances would somehow solve for him the problem of existence. But, alas, for vain hopes! Day after day, from door to door, he sought employment without success. The answers he received to his inquiries for work were ever the same: "Business was dull; they were reducing rather than increasing their forces; sorry, but if anything turned up they would let him know." At times he received just enough encouragement to make his eventual failure the more disheartening and cruel.