полная версия

полная версияThe Browning Cyclopædia: A Guide to the Study of the Works of Robert Browning

Waring. Waring was the name given by the poet to his friend Mr. Alfred Domett, C.M.G., son of Mr. Nathaniel Domett, born at Camberwell, May 20th, 1811. He matriculated at Cambridge in 1829, as a member of St. John’s College. In 1832 he published a volume of poems. He then travelled in America for two years, and after his return to London, about 1836-7, he contributed some verses to Blackwood’s Magazine. Mr. Domett afterwards spent two years in Italy, Switzerland, and other continental countries. He was called to the bar in 1841. Having purchased some land of the New Zealand Company, he went as a settler to New Zealand in 1842. In 1851 he became Secretary for the whole of that country. He accepted posts as Commissioner of Crown Lands and Resident Magistrate at Hawke’s Bay. Subsequently he was elected to represent the town of Nelson in the House of Representatives. In 1862 Mr. Domett was called upon to form a Government, which he did. Having held various important offices in the Legislature, and rendered great services to the country, he was created a Companion of the Order of St. Michael and St. George (1880). He returned to England and published several volumes of poems. His chief work is Ranolf and Amohia, full of descriptions of New Zealand scenery, and paying a warm tribute to Mr. Browning, whom he calls

“Subtlest assertor of the soul in song.”Mr. Domett suddenly disappeared from London life in the manner described in the poem. He shook off, by an overpowering impulse, the restraints of conventional life, and without a word to his dearest friends, vanished into the unknown. As the story is told in the poem, we see a man with large ideas, ambitious, full of great thoughts, inspired by a passion for great things, a man born to rule, and fretting against the restraints of the petty conventionalities of civilised life. Those about him cannot understand, and if they did could in no wise help him; he chafes and longs to break his bonds and live the freer life in which his energies can expand. The poem tells of the cold and unsympathetic criticism he received amongst his friends; and now that he has disappeared, the poet’s spirit yearns for his society once more. He wonders where he has pitched his tent, and in fancy runs through the world to seek him. He has been heard of in a ghostly sort of way. A vision of him has been narrated by one who for a few moments caught sight of him and lost him again in the setting sun. The poet reflects that the stars which set here, rise in some distant heaven. The following obituary notice of Alfred Domett, by Dr. Furnivall, appeared in the Pall Mall Gazette of November 9th, 1887. It has had the advantage of being revised and corrected in a few small details by Mr. F. Young, “Waring’s” cousin. See also an article in Temple Bar, Feb., 1896, p. 253, entitled “A Queen’s Messenger.”

“What’s Become of Waring?”– In Memoriam. (By a Member of the Browning Society.) “What’s become of Waring?” is the first line of one of Mr. Browning’s poems of 1842 (Bells and Pomegranates, Part II.), which, from its dealing with his life in London in early manhood, is a great favourite with his readers. Alas! the handsome and brilliant hero of the Browning set in the thirties died last Wednesday, at the house in St. Charles’s Square, North Kensington, where he had for many years lived near his artist son. Alfred Domett was the son of one of Nelson’s middies, a gallant seaman. He was called to the bar, and lived in the Temple with his friend ‘Joe Arnold,’ a man of great ability, afterwards Sir Joseph, Chief Justice of Bombay, who ultimately settled at Naples, where he died. Having an independency, Alfred Domett lingered in London society for a time, – one of the handsomest and most attractive men there, – till he was induced to emigrate to New Zealand, to join his cousin, William Young, the son of the London shipowner, George Frederick Young, who had bought a large tract of land in the islands. Alfred Domett landed to find his cousin drowned. He was himself soon after appointed to a magistracy with £700 a year. He had a successful career in New Zealand, – where Mr. Browning alludes to him in The Guardian Angel– became Premier, married a handsome English lady, and then returned to England. He first lived at Phillimore Place or Terrace, Kensington, and while there saw a good deal of his old friend Mr. Browning; but after he moved to St. Charles’s Square, the former companions seldom met. On the foundation of the Browning Society, Alfred Domett declined any post of honour, but became an interested member of the body. His grand white head was to be seen at all the Society’s performances and at several of its meetings. He naturally preferred Mr. Browning’s early works to the later ones. He could not be persuaded to write any account of his early London days, but said he would try to find the letters in which his friend ‘Joe Arnold’ reported to him in New Zealand the doings of their London set. Mr. Domett produced with pride his sea-stained copy of Browning’s Bells and Pomegranates, now worth twenty or thirty times its original price. Before he left England, his poem on Venice was printed in Blackwood, and very highly praised by Christopher North. (The reprint is in the British Museum.) His longer and chief poem, Ranolf and Amohia (1872), full of New Zealand scenery, and paying a warm tribute to Mr. Browning, was reprinted by him in two volumes, revised and enlarged, some four or five years ago. A lucky accident to a leg, which permanently lamed him, soon after his arrival in New Zealand, saved his life; for it prevented his accepting the invitation of some treacherous native chiefs to a banquet at which all the English guests were killed. A sterling, manly, independent nature was Alfred Domett’s. He impressed every one with whom he came in contact, and is deeply regretted by his remaining friends. We hope that Mr. Browning will in his next volume give a few lines to the memory of his early friend. Not many of the old set remain, possibly not one save the poet himself; and all his readers will rejoice to hear again of Waring, “Alfred, dear friend.” The Guardian Angel question —

“Where are you, dear old friend?”needs other answer now than that of 1855 —

“How rolls the Wairoa at your world’s far end?This is Ancona, yonder is the sea.”Notes. – Canto iv., “Monstr’ – inform’ – ingens – horren-dous”: from Vergil’s Æn. iii. 657 – “Monstrum horrendum, informe, ingens, cui lumen ademtum”: a horrid monster, misshapen, huge, from whom sight had been taken away. vi., Vishnu-land: India, where Vishnu is worshipped; the second person of the modern Hindu Trinity. He is regarded as a member of the Triad whose special function is to preserve. To do this he has nine times in succession become incarnate, and will do so once more. Avatar: the incarnation of a deity. The ten incarnations of Vishnu are – 1. Matsya-Avatar, as a fish; 2. Kurm-Avatar, as a tortoise; 3. Varaha, as a boar; 4. Nara-Sing, as a man-lion, last animal stage; 5. Vamuna, as a dwarf, first step toward the human form; 6. Parasu-Rama, as a hero, but yet an imperfect man; 7. Rama-Chandra, as the hero of Ramayána, physically a perfect man, his next of kin, friend and ally Hamouma, the monkey-god, the monkey endowed with speech; 8. Christna-Avatar, the son of the virgin Devanaguy, one formed by God; 9. Gautama-Buddha, Siddhârtha, or Sakya-muni; 10. This avatar has not yet occurred. It is expected in the future; when Vishnu appears for the last time he will come as a “saviour.” (Blavatzky, Isis Unveiled, vol. ii., p. 274.) Kremlin, the citadel of Moscow, Russia. serpentine: a rock, often of a dull green colour, mantled and mottled with red and purple. syenite: a stone named from Syene, in Egypt, where it was first found. “Dian’s fame”: Diana was worshipped by the inhabitants of Taurica Chersonesus. Taurica Chersonesus is now the country called the Crimea. Hellenic speech == Greek. Scythian strands: Taurica is joined by an isthmus to Scythia, and is bounded by the Bosphorus, the Euxine Sea, and the Palus Mæotis. Caldara Polidore da Caravaggio (1495-1543): he was a celebrated painter of frieze, etc., at the Vatican. Raphael discovered his talents when he was a mere mortar carrier to the other artists. The “Andromeda” picture, of which Browning speaks in Pauline, was an engraving from a work of this artist. “The heart of Hamlet’s Mystery”: few characters in literature have been more discussed than that of Hamlet. Schlegel thought he exhausted the power of action by calculating consideration. Goethe thought he possessed a noble nature without the strength of nerve which forms a hero. Many say he was mad, others that he was the founder of the pessimistic school. Junius: the mystery of the authorship of the famous letters of Junius is referred to. Chatterton, Thomas (1752-70): the boy poet who deceived the credulous scholars of his day by pretending that he had discovered some ancient poems in the parish chest of Redcliffe Church, Bristol. Rowley, Thomas: the hypothetical priest of Bristol, said by Chatterton to have lived in the reigns of Henry VI. and Edward IV., and to have written the poems of which Chatterton himself was the author. ii. 2, Triest: the principal seaport of the Austro-Hungarian empire, situated very picturesquely at the north-east angle of the Adriatic Sea, in the Gulf of Trieste. lateen sail: a triangular sail commonly used in the Mediterranean. “’long-shore thieves”: “along-shore men” are the low fellows who hang about quays and docks, generally of bad character.

“When I vexed you and you chid me.” (Ferishtah’s Fancies.) The first line of the seventh lyric.

Which? (Asolando, 1889.) Three court ladies make

“Trial of all who judged bestIn esteeming the love of a man.”An abbé sits to decide the wager and say who was to be considered the best Cupid catcher. First, the Duchesse maintains that it is the man who holds none above his lady-love save his God and his king. The Marquise does not care for saint and loyalist, so much as a man of pure thoughts and fine deeds who can play the paladin. The Comtesse chooses any wretch, any poor outcast, who would look to her as his sole saviour, and stretch his arms to her as love’s ultimate goal. The abbé had to reflect awhile. He took a pinch of snuff to clear his brain, and then, after deliberation, said —

“The love which to one, and one only, has reference,Seems terribly like what perhaps gains God’s preference.”White Witchcraft. (Asolando, 1889.) Magic is defined to be of two kinds – Divine and evil. Divine is white magic; black magic is of the devil. Amongst the ancients magic was considered a Divine science, which led to a participation in the attributes of Divinity itself. Philo-Judæus, De Specialibus Legibus, says: “It unveils the operations of Nature, and leads to the contemplation of celestial powers.” When magic became degraded into sorcery it was naturally abhorred by all the world, and the evil reputation attaching to the word, even at the present day, must be attributed to the fact that white witchcraft had a singular affinity for the black arts. Perhaps what is now termed “science” expresses all that was originally intended by the term white magic. The men of science of the past were not unacquainted with black arts, according to their enemies. Hence Pietro d’Abano, John of Halberstadt, Cornelius Agrippa, and other learned men of the middle ages, incurred the hatred of the clergy. Paracelsus is made expressly by Browning to abjure “black arts” in his struggles for knowledge. Burton, in his Anatomy of Melancholy, speaks of white witches. He says (Part II., sec. i.): “Sorcerers are too common: cunning men, wizards, and white-witches, as they call them, in every village, which, if they be sought to, will help almost all infirmities of body and mind —servatores, in Latin; and they have commonly St. Catherine’s wheel printed in the roof of their mouth, or in some part about them.”

[The Poem.] One says if he could play Jupiter for once, and had the power to turn his friend into an animal, he would decree that she should become a fox. The lady, if invested with the same power, would turn him into a toad. He bids Canidia say her worst about him when reduced to this condition. The Canidia referred to is the sorceress of Naples in Horace, who could bring the moon from heaven. The witch boasts of her power in this respect: —

“Meæque terra cedit insolentiæ.(Ut ipse nosti curiosus) et PoloAn quæ movere cereas imagines,Diripere Lunam.”(Horat., Canid. Epod., xvii. 75, etc.)Hudibras mentions this (Part II., 3); —

“Your ancient conjurors were wontTo make her (the moon) from her sphere dismount,And to their incantations stoop.”The Zoophilist for July 1891 gives the following, from Mrs. Orr’s Life of Browning, as the origin of the reference to the toad in the poem: “About the year 1835, when Mr. Browning’s parents removed to Hatcham, the young poet found a humble friend “in the form of a toad, which became so much attached to him that it would follow him as he walked. He visited it daily, where it burrowed under a white rose tree, announcing himself by a pinch of gravel dropped into its hole; and the creature would crawl forth, allow its head to be gently tickled, and reward the act with that loving glance of the soft, full eyes which Mr. Browning has recalled in one of the poems of Asolando.” The lines are: —

“He’s loathsome, I allow;There may or may not lurk a pearl beneath his puckered brow;But see his eyes that follow mine – love lasts there, anyhow.”“Why from the World.” The first words of the twelfth lyric in Ferishtah’s Fancies.

Why I am a Liberal was a poem written for Cassell & Co. in 1885, who published a volume of replies by English men of letters, etc., to the question, “Why I am a Liberal?”

“Why I am a Liberal“‘Why?’ Because all I haply can and do,All that I am now, all I hope to be, —Whence comes it save from future setting freeBody and soul the purpose to pursueGod traced for both? If fetters, not a few,Of prejudice, convention, fall from me,These shall I bid men – each in his degree,Also God-guided – bear, and gayly, too?But little do or can, the best of us:That little is achieved through Liberty.Who, then, dares hold, emancipated thus,His fellow shall continue bound? Not I,Who live, love, labour freely, nor discussA brother’s right to freedom. That is ‘Why.’”Will, The. (Sordello.) Mr. Browning uses the term “will” to express Sordello’s effort to “realise all his aspirations in his inner consciousness, in his imagination, in his feeling that he is potentially all these things.” See Professor Alexander’s Analysis of “Sordello,” lvii., p. 406 (Browning Society’s Papers); “The Body, the machine for acting Will” (Sordello, Book II., line 1014, and p. 477 of this work). Mr. Browning’s early opinions were so largely formed by his occult and theosophical studies that it is necessary for the full understanding of his theory of the will and its power, to study the following axioms from the work of an occult writer, Eliphas Levi, as a good summary of the teaching so largely imbibed by the poet.

“Theory of Will-Power“Axiom 1. Nothing can resist the will of man when he knows what is true and wills what is good. Axiom 2. To will evil is to will death. A perverse will is the beginning of suicide. Axiom 3. To will what is good with violence is to will evil, for violence produces disorder and disorder produces evil. Axiom 4. We can and should accept evil as the means to good; but we must never practise it, otherwise we should demolish with one hand what we erect with the other. A good intention never justifies bad means; when it submits to them it corrects them, and condemns them while it makes use of them. Axiom 5. To earn the right to possess permanently we must will long and patiently. Axiom 6. To pass one’s life in willing what it is impossible to retain for ever is to abdicate life and accept the eternity of death. Axiom 7. The more numerous the obstacles which are surmounted by the will, the stronger the will becomes. It is for this reason that Christ has exalted poverty and suffering. Axiom 8. When the will is devoted to what is absurd it is reprimanded by eternal reason. Axiom 9. The will of the just man is the will of God Himself, and it is the law of nature. Axiom 10. The understanding perceives through the medium of the will. If the will be healthy, the sight is accurate. God said, ‘Let there be light!’ and the light was. The will says: ‘Let the world be such as I wish to behold it!’ and the intelligence perceives it as the will has determined. This is the meaning of Amen, which confirms the acts of faith. Axiom 11. When we produce phantoms we give birth to vampires, and must nourish these children of nightmare with our own blood and life, with our own intelligence and reason, and still we shall never satiate them. Axiom 12. To affirm and will what ought to be is to create; to affirm and will what should not be is to destroy. Axiom 13. Light is an electric fire, which is placed by man at the disposition of the will; it illuminates those who know how to make use of it, and burns those who abuse it. Axiom 14. The empire of the world is the empire of light. Axiom 15. Great minds with wills badly equilibrated are like comets, which are abortive suns. Axiom 16. To do nothing is as fatal as to commit evil, and it is more cowardly. Sloth is the most unpardonable of the deadly sins. Axiom 17. To suffer is to labour. A great misfortune properly endured is a progress accomplished. Those who suffer much live more truly than those who undergo no trials. Axiom 18. The voluntary death of self-devotion is not a suicide, – it is the apotheosis of free-will. Axiom 19. Fear is only indolence of will; and for this reason public opinion brands the coward. Axiom 20. An iron chain is less difficult to burst than a chain of flowers. Axiom 21. Succeed in not fearing the lion, and the lion will be afraid of you. Say to suffering, ‘I will that thou shalt become a pleasure,’ and it will prove such, and more even than a pleasure, for it will be a blessing. Axiom 22. Before deciding that a man is happy or otherwise seek to ascertain the bent of his will. Tiberius died daily at Caprea, while Jesus proved His immortality, and even His divinity, upon Calvary and the Cross.”

“Wish no word unspoken.” (Ferishtah’s Fancies.) The first words of the lyric to the second poem.

Woman’s Last Word, A. (Men and Women, 1855; Lyrics, 1863; Dramatic Lyrics, 1868.) In the presence of perfect love words are often superfluous, wild, and hurtful; words lead to debate, debate to contention, striving, weeping. Even truth becomes falseness; for if the heart is consecrated by a pure affection, love is the only truth; and the chill of logic and the precision of a definition can be no other than harmful; therefore hush the talking, pry not after the apples of the knowledge of good and evil, or Eden will surely be in peril. The only knowledge is the charm of love’s protecting embrace, the only language is the speech of love, the only thought to think the loved one’s thought – the absolute sacrifice of the whole self on the altar of love; but before the altar can be approached sorrow must be buried, a little weeping has to be done; the morrow shall see the offering presented, – “the might of love” will drown alike both hopes and fears.

Women and Roses. (Men and Women, 1855; Lyrics, 1863; Dramatic Lyrics, 1868.) The singer dreams of a red rose tree with three roses on its branches; one is a faded rose whose petals are about to fall, – the bees do not notice it as they pass; the second is a rose in its perfection, its cup “ruby-rimmed,” its heart “nectar-brimmed,” – the bee revels in its nectar; the third is a baby rosebud. And in these flowers the poet sees types of the women of the ages, – the past, the present, and the future: the shadows of the noble and beautiful, or wicked women in history and poetry dance round the dead rose; round the perfect rose of the present dance the spirits of the women of to-day; round the bud troop the little feet of maidens yet unborn; and all dance to one cadence round the dreamer’s tree. The dance will go on as before when the dreamer has departed, roses will bloom then for other beholders, and other dreamers will see and remember their loveliness; the creations of the poet even must join the dance. As the love of the past, so the love to come, must link hands and trip to the measure.

Women of Browning. The best are Pompilia, in The Ring and the Book, the lady in the Inn Album, and the heroine in Colombe’s Birthday; the others, good and bad, are the wife in Any Wife to any Husband; James Lee’s Wife, Michal, Pippa, Mildred, Gwendolen, Polixena, Colombe, Anael, Domizia, “The Queen,” Constance; and the heroines of The Laboratory, The Confessional, A Woman’s Last Word, In a Year, A Light Woman, and A Forgiveness.

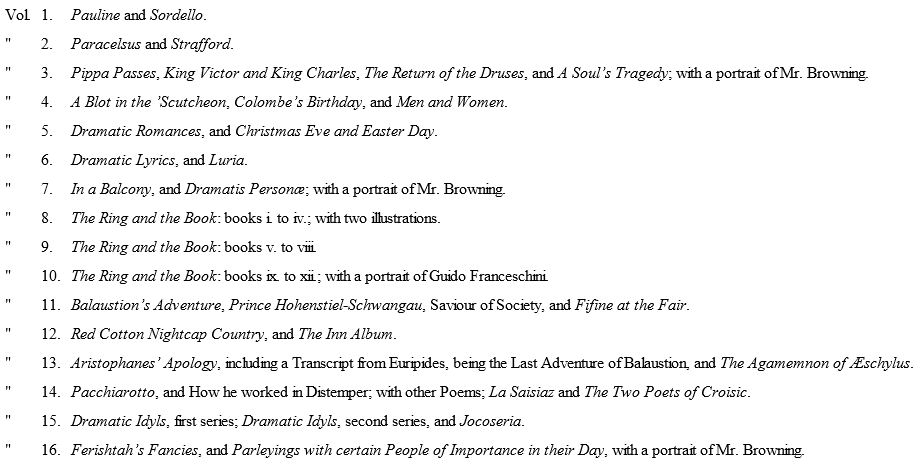

Works of Robert Browning. The new and uniform edition of the works of Robert Browning is published in sixteen volumes, small crown 8vo. This edition contains three portraits of Mr. Browning, at different periods of life, and a few illustrations. Contents of the volumes: —

Also Mr. Browning’s last volume, Asolando, Fancies and Facts.

Worst of it, The. (Dramatis Personæ, 1864.) A fleck on a swan is beauty spoiled; a speck on a mottled hide is nought. A man had angel fellowship with a young wife who proved false to him; he loves her still, and mourns that she ruined her soul in stooping to save his; he made her sin by fettering with a gold ring a soul which could not blend with his. He sorrows, not for his own loss, but that his swan must take the crow’s rebuff. He desires her good, and hopes she may work out her penance, and reach heaven’s purity at last. He will love on, but if they meet in Paradise, will pass nor turn his face.

Xanthus. (A Death in the Desert.) One of the disciples of St. John in attendance upon the dying apostle in the cave.

“You groped your way across my room.” (Ferishtah’s Fancies.) The first line of the third lyric.

“You’ll love me yet.” (Pippa Passes.) A song.

Youth and Art. (Dramatis Personæ, 1864.) A meditation on what might have been, had two young people who had the chance not missed it and lost it for ever. They lodged in the same street in Rome. The man was a sculptor who had dreams of demolishing Gibson some day, and putting up Smith to reign in his stead; the woman was a singer who hoped to trill bitterness into the cup of Grisi, and make her envious of Kate Brown. The warbler earned in those days as little by her voice as the chiseller by his work. They were poor, lived on a crust apiece, and for fun watched each other from their respective windows. She was evidently dying for an introduction to him; she fidgeted about with the window plants, and did her best to attract his attention in a quiet sort of way; she did not like his models always tripping up his stairs, which she could not ascend, and was glad to have the opportunity of showing off the foreign fellow who came to tune the piano. But life passed, he made no advances, and so in process of time she married a rich old lord, and he is a knight, R.A., and dines with the Prince. With all this show of success neither life is complete, neither soul has achieved the sole good of its earth wanderings. Their lives hang patchy and scrappy; they have not sighed, starved, feasted, despaired, and been happy. There was once the chance of these things; they were missed, and eternity cannot make good the loss. As for life “Love,” as Browning is always telling us, “is the sole good of it.” This poem may be compared with the moral of The Statue and the Bust. In the one case reasons of prudence and the restrictions of religion and society prevented the duke and the lady from following the inclinations of their hearts; in the other case mere worldly motives operated to the same end – the missing of the union of the actors’ souls. In both cases the lives were spoiled. In Youth and Art the woman’s character cuts a very poor figure: love is subordinated to her art, and that to the mere worldly advantage of a rich marriage and the opportunity of becoming “queen at bals-parés.” The man was cold, not because his art made him so, but because of his overwhelming prudence, which we may be sure did not make him a Gibson after all.