полная версия

полная версияThe Browning Cyclopædia: A Guide to the Study of the Works of Robert Browning

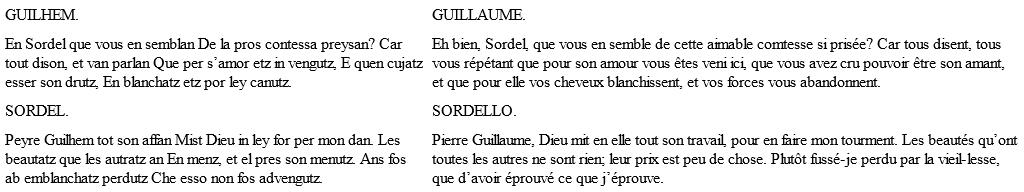

The poem of Sordello is a picture of the troublous times of the early part of the thirteenth century in North Italy, and is the history of the development of Sordello’s soul. Frederick II. is Emperor and Honorius III. is Pope. Frederick II., the noblest of mediæval princes, the man who suffered much because he was centuries in advance of his time, is too well known to need any description. To understand the causes of the conflicts in which Lombardy was engaged, we must go back to the time of Charlemagne, who took the Lombard king Desiderius prisoner, in 774, and destroyed the Lombard kingdom. Luitprand, the sovereign of the Lombards from 713 to 726, had extended the dominion of Lombardy into Middle Italy. The Popes found this dominion too formidable, so they solicited the assistance of the Frankish kings. The whole of Upper Italy had been conquered by the Lombards in the sixth century. “Charles, with the title of King of the Franks and Lombards, then became the master of Italy. In 800, the Pope, who had crowned Pepin King of the Franks, claimed to bestow the Roman Empire, and crowned his greater son Emperor of the Romans” (Encyc. Brit.). Now began a vast system in North Italy of episcopal “immunities,” which made the bishops temporal sovereigns. In the eleventh century the Lombard cities had become communes and republics, managing their own affairs and making war on their troublesome neighbours. Leagues and counter-leagues were formed, and confederacies of cities even dared to challenge the strength of Germany. Otto the Great’s empire, in the early years of the tenth century, consisted of Germany and Lombardy, with the Romagna and Burgundy; and it was Otto who fixed the principle, that to the German king belonged the Roman crown. The crown of Germany was at this period elective, although it often passed in one family for several generations. Struggles for supremacy between the two powers took place in the reign of the Emperor Henry IV. of Franconia and the papacy of Gregory VII., the famous Hildebrand. It was the struggle between Church and State destined to be fraught with so much misery. The contest ended at this period in a compromise; but most of the gains were on the side of the Pope. It was renewed with great fierceness in the reign of Frederick I. of Hohenstaufen, called Barbarossa or “Red Beard,” who came to the throne in 1152. He bestowed on the Empire the title of Holy. The cities of Lombardy were commonwealths, somewhat after the fashion of those of ancient Greece; they had grown very rich and powerful, and whilst they admitted the Emperor’s authority in theory, were averse to the practice of submission. The city of Milan, by her attacks on a weaker neighbour, who appealed to Frederick for aid, began a war which resulted in the Peace of Constance in 1183, by which the Emperor abandoned all but a nominal authority over the Lombard League. The son and successor of Frederick – Henry VI. – began to reign in 1190; he married Constance, heiress of the Norman kingdom of Sicily, which was a fief of the papal crown. After the death of Henry VI., Philip, his brother, began to reign, in 1198. In 1208, Otho IV., surnamed the Superb, ascended the throne, and was crowned Emperor. The next year he was excommunicated and deposed. In 1212, Frederick II., King of Sicily, who was the son of Henry VI., began his reign, he received the German crown at Aix-la-Chapelle, 1215, and the Imperial crown of Rome, 1230. When he died he possessed no fewer than six crowns, – the Imperial crown, and the crowns of Germany, Burgundy, Lombardy, Sicily, and Jerusalem. He had assumed the cross, and in 1220 he left his Empire for a space of fifteen years, to accomplish the crusade and to carry on the war with the Lombard cities and the Pope (Gregory IX.). John of Brienne, the dethroned King of Jerusalem, who was afterwards Emperor of the East, had a daughter named Yolande, whom Frederick married. He sent a bunch of dates to Frederick to remind him of his promised crusade. When that sovereign formed the army of the East, he left his young son Henry to represent him in Germany. Frederick was deposed by his subjects, and died in 1250, naming his son Conrad as his successor. In the beginning of the reign of Conrad III., 1138, the Imperial crown was contested by Henry the Proud Duke of Saxony. It was at this time that the contests between the factions, afterwards so famous in history as those of the Guelfs and the Ghibellines, began. Duke Henry had a brother named Welf, the leader of the Saxon forces. They used his name as their battle cry, and the Swabians responded by crying out the name of the village where their leader, the brother of Conrad, had been born – namely, Waibling. The Welfs and the Waiblings were therefore the originals of the terms Guelfs and Ghibellines. – “The Romano Family.” During the reign of Conrad II. (1024-39) a German gentleman, named Eccelino, accompanied that Emperor to Italy, with a single horse, and so distinguished himself that, as a reward for his services, he received the lands of Onaro and Romano in the Trevisan marches. This founder of a powerful house, famous for its crimes, was succeeded by Alberic, and he by another Eccelino, called the First and also le Bègue – ‘the Stammerer.’ These gentlemen largely augmented their patrimony, acquiring Bassano, Marostica, and many other estates situated to the north of Vicenza, Verona, and Padua; so that their fief formed a small principality, equal in power to either of its neighbouring republics; and as the factions of the towns sought to strengthen themselves by alliances with them, the Seigneurs de Romano were soon regarded as the chiefs of the Ghibelline party in all Venetia. Eccelin le Bègue and Tisolin de Campo St. Pierre, a Paduan noble, were warm friends, and the latter was married to a daughter of the former, and had a son grown to manhood. Cecile, orphan daughter and heiress of Manfred Ricco d’Abano, was offered in marriage, by her guardians, to the young St. Pierre; but the father before concluding the advantageous alliance, thought it proper to consult his friend and father-in-law, Eccelino. That gentleman, however, wished to obtain this great fortune for his own son, and secretly bribed the lady’s guardians to deliver her up to him, when he carried her off to his castle of Bassano and then hurriedly married her to his son. This treachery made the whole family of Campo St. Pierre indignant, and they vowed vengeance. They had not long to wait for their opportunity. Several months after the marriage, the wife of the young Eccelino went on a visit to her estates in the Paduan territory, with a suite more brilliant than valiant. Tisolin’s son, Gerard, who was to have been Cecile’s husband, and was now her nephew, seized her and carried her off from the midst of her retinue to his castle of St. André. Cecile, escaping after a time, returned to Bassano and related her terrible misfortune to her husband, who at once repudiated her, and she afterwards married a Venetian nobleman. The two families had, however, thus founded a mutual hate, which descended from father to son, and cost many lives and much blood. In the meantime, Eccelino II.’s power was augmented by this marriage and the one he afterwards contracted. He made alliances with the republics of Verona and Padua; and he soon required their aid, for in 1194, when one of his enemies was chosen podesta of Vicenza, he, his family, and the whole faction of Vivario, were exiled from the city. Before submitting, he undertook to defend himself by setting fire to his neighbours’ houses; and a great portion of the town was destroyed during the insurrection. These were the first scenes of disorder and bloodshed which greeted the eyes of Eccelino III. or the Cruel, who was born a few weeks before. Exile from Vicenza was not a severe sentence for the lords of Romano; for they retired to Bassano, in the midst of their own subjects, and called around them their partisans, who were persecuted as they themselves were, without the same resources. By the aid thus given with apparent generosity, they degraded their associates, transforming their fellow-citizens into mercenary satellites, and increasing their influence in the town, from which their exile could not be of long duration. The Veronese interfered to establish peace in Vicenza. They had the Romanos recalled, with all their party; and an arrangement was made by which two podestas were chosen at the same time, one by each party. In 1197, however, the Vicenzese again chose a single podesta, hostile to Eccelino, and this time not only banished the Romanos, but declared war against them, and sent troops to besiege Marostica. Eccelino, placed between three republics, could choose his own allies; and decided now upon Padua. The Paduan army attacked that of Vicenza, near Carmignano, and took two thousand prisoners. The Vicenzese called upon the Veronese to assist them, and together they invaded the Paduan territory, desolating it up to the very walls of the city, and so frightening the Paduans that they delivered up all of their prisoners without waiting to consult Eccelino. That prince took this opportunity to break with Padua, and called upon Verona to arbitrate between him and Vicenza, giving them as hostages his young daughter and his strongest two castles, Bassano and Anganani. By this thorough confidence he so won the affection of the podesta of Verona that he concluded peace for him with Vicenza and the whole Guelf party, and then returned his castles to him. The Paduans revenged themselves by confiscating Onaro, the first estate possessed by the Romano family in Italy. —Salinguerra. William Marchesella des Adelard, chief of the Guelf party in Ferrara, had the misfortune to see all the male heirs of his house, his brother and all his sons, perish before him. An only daughter of his brother, named Marchesella, remained, and he declared her the sole heiress to his immense estates, naming the son of his sister as heir should Marchesella die without children. Tired of warfare, and hoping to ensure peace to his distracted country, he determined to do so by uniting the leading families of the two factions. Salinguerra, son of Torrello, was at the head of the Ghibellines in Ferrara; and William not only offered his niece to him in marriage, but actually before his death placed her, then a child of seven years, in his hands to be reared and educated. The Guelfs were, however, unwilling to permit the heiress of their leading family to remain in the hands of their enemies; and they could not consent to transfer their affection and allegiance to those with whom they had fought for so long a time. They therefore found an opportunity to surprise Salinguerra’s palace, and abduct Marchesella, whom they placed in the palace of the Marquis d’Este, choosing Obizzo d’Este to be her husband, and placing her property in the hands of the Marquis. In the end Marchesella died before she was married; her cousins, designated by William, in this event, to be his heirs, were afraid to claim the estates, and the whole property continued in the hands of the Este family. In the meantime the insult offered to Salinguerra was keenly resented. The abduction took place in 1180, and for nearly forty years afterwards civil war continued within the walls of Ferrara without ceasing. During those years, ten times one faction drove the other out of the city, ten times all the property of the vanquished was given up to pillage, and all their houses razed to the ground. —Eccelino and Salinguerra. In 1209 Otho IV. entered Italy, and held his court near Verona. All the chief lords of Venetia – but especially Eccelino II., de Romano, and Azzo VI., Marquis d’Este – were summoned to attend. Those two gentlemen had profited by the long interregnum which preceded Otho’s reign to increase their influence in the marches, and the factions were more bitter against each other than ever. These factions had different reasons for existing in the different towns; but they quickly adopted the newly introduced names of Guelf and Ghibelline, and a common tie was thus suddenly formed between the factions in the various places. Thus, by the mere adoption of a name, Salinguerra in Ferrara and the Montecci in Verona, found themselves allies of Eccelino; and, on the other hand, the Adelards of Ferrara, Count St. Bonifazio at Verona and Mantua, and the Campo St. Pierre at Padua, were all allies of the Marquis d’Este. The year before, Este, after a short banishment, had re-entered Ferrara, and had succeeded in being declared lord of that city, – the first time that an Italian republic abandoned its rights for the purpose of voluntarily submitting to a tyrant. About the same time the Marquis had gained an important victory over Eccelino and his party; but, at the moment when the Emperor entered Italy, Eccelino had gained some advantages over the Vicenzese, and thought himself on the point of capturing the city. Azzo marched against him, whereupon Salinguerra entered Ferrara and drove out all of Azzo’s adherents. The summons sent to the chiefs to meet the Emperor no doubt prevented a bloody battle and a useless massacre. (See note, p. 500; see also the article, Taurello Salinguerra, in this work.) In 1235, after a long and turbulent reign, full of vicissitudes, Eccelino II. retired into a monastery, and divided his principality between his two sons, Eccelino III. and Alberic. The latter remained at Treviso; but Eccelino III. became very powerful, kept all Italy in turmoil, and was notorious for his infamous tyrannies and cruelties. In 1255 he was excommunicated by the Pope, Alexander IV., and a crusade was preached against him. He fought against his enemies from that time, with varying success and stubborn courage, until 1259, when he was wounded in battle and taken prisoner. The leaders of the enemy with difficulty protected him from the fury of the soldiers and the people; but he himself tore the bandages from his wounds, and died on the eleventh day of his captivity. All the cities which he had conquered and oppressed at once revolted; and Treviso, where Alberic had reigned ever since his fathers abdication, revolted and drove him out. Alberic, with his family, took refuge in his fortress of San Zeno, in the Euganean mountains; but the league of Guelf cities declared against him, and the troops of Venice, Treviso, Vicenza, and Padua surrounded the castle, where they were soon joined by the Marquis d’Este. Traitors delivered up the outworks; but Alberic and his wife, two daughters and six sons, took refuge on the top of a tower. After three days, compelled by hunger, he delivered himself up to the Marquis, at the same time reminding him that one of his daughters was the wife of Renaud d’Este. In spite of this, however, he and his family were all murdered and torn to pieces, and their dismembered bodies divided among all the cities over which the hated Romano family had tyrannised. In 1240 Gregory IX. preached a crusade against the Emperor Frederick II., and a crusading army surrounded Ferrara, where Salinguerra, then more than eighty years old, had reigned for some time as prince and as head of the Ghibellines. He successfully defended the city for some time; but when attending a conference, to which he was invited by his enemies, he was treacherously captured and sent to Venice, where, after five years’ imprisonment, he died.” [S.]

[The Poem.] Sordello is Browning’s Hamlet, and is the most obscure of all Mr. Browning’s poems. It has been aptly compared to a vast palace, in which the architect has forgotten to build a staircase. Its difficulties are not merely those which are inseparable from an attempt to trace the development of a soul, – such a work without obscurity could only deal with a very simple soul, – but are consequent on the remoteness of time in which the political events and historical circumstances which formed the environment of Sordello’s existence took place, and the partial interest which the majority of readers feel concerning those events. The work deals with the struggles of the Guelfs and Ghibellines; and it is necessary to possess a fair knowledge of the history of the times, places, and persons concerned before we can grasp the mere outlines of the story. It must be admitted, whether we allow the charge of obscurity or not, that Mr. Browning never helps his reader. He may or may not actually hinder him: it is certain that he does not go out of his way to assist him. The first step towards understanding Sordello, then, is to gain some acquaintance with the period and personages of the story. The work is full of beauty. Probably no poet ever poured out such wealth of richest thought with such princely liberality as Mr. Browning has done in this much discussed poem. It is like a Brazilian forest, in which, though we shall almost certainly lose our way, it will be amidst such profusion of floral loveliness that it will be a delight to be buried in its depths.

Book I. – The poem in its first scene places us in imagination in Verona six hundred years ago. A restless group has gathered in its market-place to discuss the news which has arrived, – that their prince, Count Richard of St. Boniface, the great supporter of the cause of the Guelfs, who had joined Azzo, the lord of Este, to depose the Ghibelline leader, Tauzello Salinguerra, from his position in Ferrara, has become prisoner in Ferrara; and in consequence immediate aid is demanded from the “Lombard League of fifteen cities that affect the Pope.” The Pope supported the Guelf cause, the Kaiser that of the Ghibellines. The leaders of the two causes are described, and the principles of which each was the representative. We are next introduced to Sordello; not in his youth, but in a supreme moment before the end of his career – a moment which has to determine his future. How this pregnant moment has come about, and how the past has fashioned the present, the poet now proceeds to explain. We are taken back to the castle of Goïto, when Sordello was a boy already of the regal class of poets, musing by the marble figures of the fountain, and finding companions in the embroidered figures on the arras. Adelaide, wife of Eccelino da Romano, the Ghibelline prince, was mistress of the castle. Sordello was only a page, known only as the orphan of Elcorte, an archer, who, in the slaughter of Vicenza, had saved his mistress and her new-born son at the cost of his own life. The son was afterwards known as Eccelin the Cruel. Sordello led the ideal life of a poet child at Goïto. All nature was a scene of enchantment to him, was endowed with form and colour from his own rich fancy. But Sordello was not content with living his own life, he must combine in his person the lives of his imaginary heroes. He will be perfect: he chooses Apollo as his ideal: he must love a woman to match his high ambition. He aims at Palma, Eccelin’s only child by his former wife, Agnes Este, but who has been already set apart, for reasons of state, as the wife of Count Richard of St. Boniface, the Guelf. Palma, however, it is reported in the castle, will refuse him. Sordello anxiously awaits his opportunity. The return of Adelaide to the castle demands the services of the troubadours: Sordello’s chance lies this way.

Book II. shows us Sordello setting forth on a bright spring day, full of hope that he will meet Palma. Arriving at Mantua, he finds a Court of Love, in which his lady sits enthroned as queen, and the troubadour Eglamor contending for her prize against all comers. Eglamor seems to make but a poor affair of the story he is singing. He ceases. Sordello knows the story too, and feels that he can do better with it. He springs forward, and with true inspiration sings a new song to the old idea transfigured. He has won the prize from Palma’s hands. Swooning with joy, he is carried back to Goïto, the poet’s crown on his brow and Palma’s scarf round his neck. Eglamor is dead with spite, and the troubadours have a new chief. Thus was Sordello poet, Master of the Realms of Song. He will slumber: he can arise in his strength any day. He is summoned to Mantua to sing to order. He finds the idea of work distasteful; but he conquers, and is crowned with honours. But he feels he has only been loving song’s results, not song for its own sake; his failure to reach his ideal destroys the pleasure derived from his success. Soon the true Sordello vanished, sundered in twain, the poet thwarting the man. The man and bard was gone; internal struggles frittered his soul; he became too contemptuous, and so he neither pleased his patrons nor himself. He falls lower and lower, abjures the soul in his songs, and contents himself with body. His degradation is complete. Meanwhile Adelaide dies, and Eccelin resolves to forsake the world and the Emperor, and come to terms with the Pope. Taurello rages furiously at this news, and returns to Mantua. Sordello is chosen to sound his praises. “’Tis a test, remember,” says Naddo. But Sordello loathes the task: he will not sing at all, and runs away to Goïto.

Book III. – Once more at his old home, Mantua becomes but a dream. Sordello, well or ill, is exhausted: rather than imperfectly reveal himself, he will remain unrevealed. He will remain himself, instead of attempting to project his soul into other men. He spent a year with Nature at Goïto, but as one defeated, – youth gone, love and pleasure foregone, and nothing really done. With an all-embracing sympathy he has not himself really lived. When Nature makes a mistake she can rectify it. He must perish once, and perish utterly. He should have brought actual experience of things obtained by sterling work to correct his mere reflections and observations. He may do something yet: though youth is gone, life is not all spent. He has the will to do, – what of the means? Resolution having thus been taken, the means are suddenly discovered. Naddo arrives as messenger from Palma, telling how Eccelin has distributed his wealth to his two sons, has married them to Guelf brides, and has retired to a monastery; that Palma is betrothed to Richard of St. Boniface, and Sordello must compose a marriage hymn. Sordello seizes the opportunity, and hastens to meet Palma at Verona. We have now arrived at the point at which the poem of Sordello opens in Book I. He has to hear a strange confession from the lips of Palma. If Sordello had been paralysed by indecision, she too had done nothing, because she was awaiting an “out-soul.” Weary with waiting for her complement, which should enable her to live her proper life, she had conceived a great love for Sordello when he burst upon the scene at the Love Court. To win Sordello for herself and her cause henceforth was her life-object. When Adelaide died this became practicable. She had heard the astonishing dying confession of Adelaide, and had witnessed Eccelin’s visit to the death-chamber when he came to undo everything which Adelaide had done. He had resolved to reconcile the Guelf and Ghibelline factions. Taurello determined to use Palma to support the Ghibellines. Palma, as head of the house, agreed to this; but it was arranged that the project should not at present be made public. She must profess her intention to carry out the arrangement which Taurello had made, before he entered on the religious life, of marrying the Guelf, Count Richard. Taurello has thus entrapped the Count, and has him in prison at Ferrara. Palma’s father, Eccelin, blots out all his old engagements. All now rests with Palma, and she arranges to fly with Sordello on the morrow as arbitrators to Taurello at Ferrara. Now is one round of Sordello’s life accomplished. Mr. Browning here makes a long digression, beginning, “I muse this on a ruined palace-step at Venice.” The City in the Sea seems to him a type of life: —

“Life, the evil with the good,Which make up living, rightly understood;Only do finish something!”No evil man is past hope; if he has not truth, he has at least his own conceit of truth; he sees it surely enough: his lies are for the crowd. Good labours to exist; though Evil and Ignorance thwart it. In this life we are but fitting together an engine to work in another existence. He sees profound disclosures in the most ordinary type of face: the world will call him dull for this, as being obscure and metaphysical. There are poets who are content to tell a simple story of impressions; another class presents things as they really are in a general, and not, as in the previous class, in an individual sense; but the highest class of all brings out the deeper significance of things which would never have been seen without the poet’s aid. These are the Makers-see – obviously a higher type of genius than the Seers. “But,” asks the objector, “what is the use of this?” It is quite true that men of action, like Salinguerra, are not unwisely preferred to dreamers like Sordello: they, at least, do the world’s work somehow; this is better than talking about it. But, at any rate, there is no harm done in compelling the Makers-see to do their duty. It is their province to gaze through the “door opened in heaven,” and tell the world what they see, and make us see it too, as did John in Patmos Isle. And so Mr. Browning has analysed for us the soul of Sordello; but he expects no reward for it. The world is too indolent to look into heaven with John, or into hell with Dante.