полная версия

полная версияThe Life of Albert Gallatin

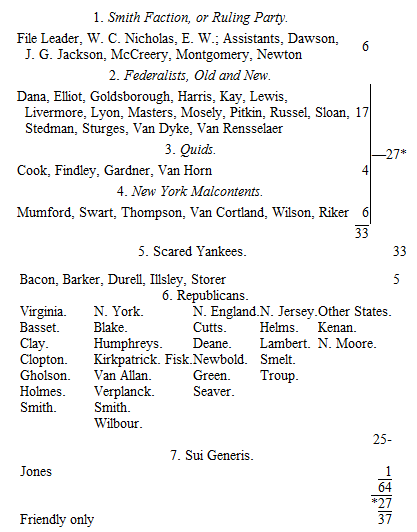

The votes of February 2 and February 4, 1809, carried a deeper significance to Mr. Gallatin than to any one else, for they did not stand alone. Congress had already shown that it meant to accept his control no longer, and this was no mere panic and no result of New England defection. He had at last to meet the experience of defeat where he had supposed himself strongest. As has been seen, the administration of naval affairs had always been repugnant to Mr. Gallatin’s wishes; the time when he had opposed a moderate navy had long passed, and, as Secretary of the Treasury, he had never wished to diminish the efficiency or lessen the force of the few frigates we had; but he conceived that the management of the Department under Mr. Robert Smith was wasteful and inefficient. Very large sums of money had been spent, for which there was little to show except one hundred and seventy gun-boats, which had cost on an average $9000 each to build and would cost $11,500 a year in actual service. At the beginning of the session it had been distinctly intimated by the Executive that no present increase of force was required; but suddenly, on the 4th January, 1809, the Senate adopted a bill which directed that all the frigates and other armed vessels of the United States, including the gun-boats, should be immediately fitted out, officered, manned, and employed. The law was mandatory; it required the immediate employment of some six thousand seamen and the appropriation of some six million dollars, and this excessive expenditure on the part of the navy was not accompanied by any corresponding measures for shore armaments and defences. If war did not take place the expense was entirely lost. Had these six millions been expended in buying arms, constructing fortifications and putting them in readiness for war, or in organizing and arming the militia, or in building frigates and ships of the line, the government would have had something to show for them; but to waste the small national treasure before war began; to support thousands of seamen in absolute idleness, with almost a certainty that the moment a British frigate came within sight they would have to run ashore for safety, seemed insane extravagance. Yet when the Senate’s amendment came before the House it was adopted on the 10th January by a vote of 64 to 59, in the teeth of Mr. Gallatin’s warm remonstrances. Among his papers is the following curious analysis of this vote.

THE NAVY COALITION OF 1809By whom were sacrificed Forty Republican members, nine Republican States, The Republican cause itself, and the people of the United States, To a system of Favoritism, extravagance, parade, and folly—

The meaning of all this confusion was soon made clear to Gallatin. A web of curious intrigue spun itself over the chair which Mr. Madison now left empty in the Department of State; there was no agreement upon the person who was to fill it, and who would, perhaps, be made thereby the most prominent candidate for succession to the throne itself. Not until his inauguration approached did Mr. Madison distinctly give it to be understood that he intended to make Mr. Gallatin his Secretary of State. This intention roused vehement opposition among Senators. Leib and the Aurora influence were of course hostile to Gallatin, and Leib now found a formidable ally in William B. Giles, Senator from Virginia. Giles made no concealment of his opposition. “From the first,” wrote Mr. Wilson Cary Nicholas, “Mr. Giles declared his determination to vote against Gallatin. I repeatedly urged and entreated him not to do it; for several days it was a subject of discussion between us. There was no way which our long and intimate friendship would justify, consistent with my respect for him, in which I did not assail him. To all my arguments he replied that his duty to his country was to him paramount to every other consideration, and that he could not justify to himself permitting Gallatin to be Secretary of State if his vote would prevent it.” “The objection to him that I understood had the most weight, and that was most pressed in conversation, was that he was a foreigner. I thought it was too late to make that objection. He had for eight years been in an office of equal dignity and of greater trust and importance.”

But Leib and Giles, separate or combined, were not strong enough to effect this object; they needed more powerful allies, and they found such in the Navy influence, represented in the Senate chiefly by General Smith, Senator from Maryland, brother of the Secretary of the Navy, and brother-in-law of Wilson Cary Nicholas. General Smith joined the opposition to Gallatin. An effort appears to have been made to buy off the vote of General Smith; it is said that he was willing to compromise if his brother were transferred to Mr. Gallatin’s place in the Treasury, and that Mr. Madison acquiesced in this arrangement, but Gallatin dryly remarked that he could not undertake to carry on both Departments at once, and requested Mr. Madison to leave him where he was. Mr. Madison then yielded, and Robert Smith was appointed Secretary of State.

Mr. J. Q. Adams, who at just this moment was rejected as minister to Russia by the same combination, has left an unpublished account of this affair:

MADISON AND GALLATIN. 1809“In the very last days of his [Jefferson’s] Administration there appeared in the Republican portion of the Senate a disposition to control him in the exercise of his power. This was the more remarkable, because until then nothing of that character had appeared in the proceedings of the Senate during his Administration. The experience of Mr. Burr and of John Randolph had given a warning which had quieted the aspirings of others, and, with the exception of an ineffectual effort to reject the nomination of John Armstrong as minister to France, there was scarcely an attempt made in the Senate for seven years to oppose anything that he desired. But in the summer of 1808, after the peace of Tilsit, the Emperor Alexander of Russia had caused it to be signified to Mr. Jefferson that an exchange of ministers plenipotentiary between him and the United States would be very agreeable to him, and that he waited only for the appointment of one from the United States to appoint one in return. Mr. Jefferson accordingly appointed an old friend and pupil of his, Mr. William Short, during the recess of the Senate, and Mr. Short, being furnished with his commission, credentials, and instructions, proceeded on his mission as far as Paris. Towards the close of the session of Congress he nominated Mr. Short to the Senate, by whom the nomination was rejected. This event occasioned no small surprise. It indicated the termination of that individual personal influence which Mr. Jefferson had erected on the party division of Whig and Tory. It was also the precursor of a far more extensive scheme of operations which was to commence, and actually did commence, with the Administration of Mr. Madison.

“He had wished and intended to appoint Mr. Gallatin, who had been Secretary of the Treasury during the whole of Mr. Jefferson’s Administration, to succeed himself in the Department of State, and Mr. Robert Smith, who had been Secretary of the Navy, he proposed to transfer to the Treasury Department. He was not permitted to make this arrangement. Mr. Robert Smith had a brother in the Senate. It was the wish of the individuals who had effected the rejection of Mr. Short that Mr. Robert Smith should be Secretary of State, and Mr. Madison was given explicitly to understand that if he should nominate Mr. Gallatin he would be rejected by the Senate.

“Mr. Robert Smith was appointed. This dictation to Mr. Madison, effected by a very small knot of association in the Senate, operating by influence over that body chiefly when in secret session, bears a strong resemblance to that which was exercised over the same body in 1798 and 1799, with this difference, that the prime agents of the faction were not then members of the body, and now they were.

“In both instances it was directly contrary to the spirit of the Constitution, and was followed by unfortunate consequences. In the first it terminated by the overthrow of the Administration and by a general exclusion from public life of nearly every man concerned in it. In the second its effect was to place in the Department of State, at a most critical period of foreign affairs and against the will of the President, a person incompetent, to the exclusion of a man eminently qualified for the office. Had Mr. Gallatin been then appointed Secretary of State, it is highly probable, that the war with Great Britain would not have taken place. As Providence shapes all for the best, that war was the means of introducing great improvements in the practice of the government and of redeeming the national character from some unjust reproaches, and of strongly cementing the Union. But if the people of the United States could have realized that a little cluster of Senators, by caballing in secret session, would place a sleepy Palinurus at the helm even in the fury of the tempest, they must almost have believed in predestination to expect that their vessel of state would escape shipwreck. This same Senatorial faction continued to harass and perplex the Administration of Mr. Madison during the war with Great Britain, till it became perceptible to the people, and the prime movers losing their popularity were compelled to retire from the Senate. They left behind them, however, practices in the Senate and a disposition in that body to usurp unconstitutional control, which have already effected much evil and threaten much more.”

Thus the Administration of Mr. Jefferson, whose advent had been hailed eight years before by a majority of the nation as the harbinger of a new era on earth; the Administration which, alone among all that had preceded or were to follow it, was freighted with hopes and aspirations and with a sincere popular faith that could never be revived, and a freshness, almost a simplicity of thought that must always give to its history a certain indefinable popular charm like old-fashioned music; this Administration, into which Mr. Gallatin had woven the very web of his life, now expired, and its old champion, John Randolph, was left to chant a palinode over its grave: “Never has there been any Administration which went out of office and left the nation in a state so deplorable and calamitous.”

Under such conditions, with such followers and such advisers, Mr. Madison patched up his broken Cabinet and his shattered policy; broken before it was complete, and shattered before it was launched. He had to save what he could, and by rallying all his strength in Congress he succeeded in preserving a tolerable appearance of energy towards the belligerent nations; but in fact the war-policy was defeated, and a small knot of men in the Senate were more powerful than the President himself. The Cabinet was an element not of strength but of weakness, for whatever might be Mr. Smith’s disposition he could not but become the representative of the group in the Senate which had forced him into prominence. Under such circumstances, until then without a parallel in our history, government, in the sense hitherto understood, became impossible.

Had Mr. Gallatin followed his own impulses, he would now have resigned his seat in the Cabinet and returned to his old place in Congress. That course, as the event proved, would have been the wisest for him, but his ultimate decision to remain in the Treasury was nevertheless correct. He had at least an even chance of regaining his ground and carrying out those ideas to which his life had been devoted; the belligerents might return to reason; the war in Europe could not last forever; the country might unite in support of a practicable policy; at all events there was no immediate danger that the government would go to pieces, and heroic remedies were not to be used but as a last resort. So far as Mr. Madison was concerned, the question was not whether he was to be deserted, but in what capacity Mr. Gallatin could render him the most efficient support.

Suddenly the skies seemed to clear, and the new Administration for a brief moment flattered itself that its difficulties were at an end. Mr. Erskine received the reply of Mr. Canning to his letters of December 3 and 4, and this reply declared in substance that if the United States would of her own accord abandon the colonial trade and allow the British fleet to enforce that abandonment, England would withdraw her orders in council. This was, it is true, a matter of course. Mr. Canning’s object in imposing the orders in council, though nominally retaliatory upon France, had been really to counteract Napoleon’s Continental policy and to save British shipping and commerce from American competition, and his condition of withdrawing the orders could only be that America should abandon her shipping and employ British ships of war in destroying her own trade. Mr. Erskine, however, conceived that a loose interpretation might be put on these conditions. After communicating their substance to the Secretary of State and receiving the reply that they were inadmissible, he “considered that it would be in vain to lay before the government of the United States the despatch in question, which I was at liberty to have done in extenso had I thought proper.”96 He therefore set aside his instructions and proceeded to act in what he conceived to be their spirit. A hint thrown out by Mr. Gallatin that the substitution of non-intercourse for embargo had so altered the situation as to put England in a more favorable position with reference to France, served as the ground for Mr. Erskine’s propositions; but these propositions, in fact, rested on no solid ground whatever, for in them Mr. Erskine entirely omitted all reference to an abandonment of the colonial trade, and while the American government professed its readiness to abandon that trade so far as it was direct from the West Indies to Europe, this was all the foundation Mr. Erskine had for considering as fulfilled that condition of his instructions by which America was to abjure all colonial trade, direct and indirect, and allow the British fleet to enforce this abjuration.

On this slender basis, and without communicating his authority, Mr. Erskine, early in April, 1809, made a provisional arrangement with the Secretary of State by which the outrage on the Chesapeake was atoned for, and the orders in council withdrawn. The President instantly issued a proclamation bearing date the 19th April, 1809, declaring the trade with Great Britain renewed. Great was the joy throughout America; so great as for the moment almost to obliterate party distinctions. When Congress met on May 22, for that session which had been called to provide for war, all was peace and harmony; John Randolph was loudest in singing praises of the new President, and no one ventured to gainsay him. The Federalists exulted in the demonstration of their political creed that Mr. Jefferson had been the wicked author of all mischief, and that the British government was all that was moderate, just, and injured.

The feelings of Mr. Canning on receiving the news were not of the same nature. The absurd and ridiculous side of things was commonly uppermost in his mind, and in the whole course of his stormy career there was probably no one event more utterly absurd than this. His policy in regard to the United States was simple even to crudeness; he meant that her neutral commerce, gained from England and France, should be taken away, and that, if possible, she should not be allowed to fight for it. In carrying out this policy he never wavered, and he was completely successful; even an American can now admire the clearness and energy of his course, though perhaps it has been a costly one in its legacy of hate. That one of his subordinates should undertake to break down his policy and give back to the United States her commerce, and that the United States should run wild with delight at this evidence of Mr. Canning’s defeat and the success of her own miserable embargo, was an event in which the ludicrous predominated over the tragic. Mr. Canning made very short work of poor Mr. Erskine; he instantly recalled that gentleman and disavowed his arrangement; but in order to prevent war he announced that a new minister would be immediately sent out. Even this civility, however, was conceded with very little pretence of a disposition to conciliate, and the minister chosen for the purpose was calculated rather to inspire terror than good-will. Mr. Rose had at least borne an exterior of civility, and had affected a decent though patronizing benevolence. Mr. Jackson made no such pretensions. His feelings and the object of his mission were odious enough at the time, and, now that his private correspondence has been published,97 it can hardly be said that, however insolent the American government may have thought him, he was in the least degree more insolent than his chief intended him to be.

The news of Mr. Canning’s disavowal reached America in July, and spread consternation and despair. Mr. Gallatin found himself involved in a sort of controversy with Mr. Erskine, resulting from the publication of Erskine’s despatches in England, and, although he extricated himself with skill, the result could at best be only an escape. The non-intercourse had to be renewed by proclamation, and the Administration could only look about and ask itself in blank dismay what it could do next.

GALLATIN TO JOSEPH H. NICHOLSONWashington, 20th April, 1809.Dear Sir, – I do not perceive, unless the President shall otherwise direct, anything that can now prevent my leaving this on Sunday for Baltimore. I fear that Mrs. Gallatin will not go; she is afraid to leave the children, who have all had slight indispositions. Yet she would, I think, be the better for a friendly visit to Mrs. Nicholson and croaking with you. As you belong to that tribe, I presume that, although you found fault yesterday with Mr. Madison because he did not make peace, you will now blame him for his anxiety to accommodate on any terms. Be that as it may, I hope that you will get 1 dollar and 60/100 for your wheat. And still you may say that you expected two dollars. Present my best respects to Mrs. Nicholson.

Yours truly.Eustis may have his faults, but I will be disappointed if he is not honorable and disinterested.

GALLATIN TO JOHN MONTGOMERYWashington, 27th July, 1809.… The late news from England has deranged our plans, public and private. I was obliged to give up my trip to Belair, have also postponed our Virginia journey, and have written to Mr. Madison that I thought it necessary that he should return here immediately. We have not yet received any letters from Mr. Pinckney nor any other official information on the subject. Even Mr. Erskine, who is, however, expected every moment, has not written. I will not waste time in conjectures respecting the true cause of the conduct of the British government, nor can we, until we are better informed, lay any permanent plan of conduct for ourselves. I will only observe that we are not so well prepared for resistance as we were one year ago. All or almost all our mercantile wealth was safe at home, our resources entire, and our finances sufficient to carry us through during the first year of the contest. Our property is now all afloat; England relieved by our relaxations might stand two years of privations with ease; we have wasted our resources without any national utility; and, our Treasury being exhausted, we must begin our plan of resistance with considerable and therefore unpopular loans. All these considerations are, however, for Congress; and at this moment the first question is, what ought the Executive to do? It appears to me from the laws and the President’s proclamation, that as he had no authority but that of proclaiming a certain fact on which alone rested the restoration of intercourse, and that fact not having taken place, the prohibitions of the Non-Intercourse Act necessarily revive in relation to England, and that a proclamation to that effect should be the first act of the Executive. If we do not adopt that mode, our intercourse with England must continue until the meeting of Congress, whilst her orders remain unrepealed and our intercourse with France is interdicted by our own laws. This would be so unequal, so partial to England and contrary to every principle of justice, policy, and national honor, that I hope the Attorney-General will accede to my construction and the President act accordingly.

The next question for the Executive is how we shall treat Mr. Jackson; whether and how we will treat with him. That must, it is true, depend in part on what he may have to say. But I have no confidence in Canning & Co., and if we are too weak or too prudent to resist England in the direct and proper manner, I hope at least that we will not make a single voluntary concession inconsistent with our rights and interest. If Mr. Jackson has any compromise to offer which would not be burthened with such, I will be very agreeably disappointed. But, judging by what is said to have been the substance of Mr. Erskine’s instructions, what can we expect but dishonorable and inadmissible proposals? He is probably sent out, like Mr. Rose, to amuse and to divide, and we will, I trust, by coming at once to the point, bring his negotiation to an immediate close…

One may reasonably doubt whether during the entire history of the United States government the difficulties of administration have ever been so great as during the years 1809-11. Peace usually allows great latitude of action and of opinion without endangering the national existence. War at least compels some kind of unity; the path of government is then clear. Even in 1814 and in 1861 the country responded to a call; but in 1809 and 1810 the situation was one of utter helplessness. The session of 1808-9 had proved two facts: one, that the nation would not stand the embargo; the other, that it could not be brought to the point of war. So far as Mr. Madison and his Administration are concerned, it is safe to say that they would at any time have accepted any policy, short of self-degradation, which would have united the country behind them. As for Mr. Gallatin, he had yielded to the embargo because it had the support of a great majority of Congress; he had done his utmost to support the only logical consequence of the embargo, which was war. Congress had rejected both embargo and war, and had in complete helplessness fallen back on a system of non-intercourse which had most of the evils of embargo, much of the expense of war, and all the practical disgrace of submission. He could do nothing else than make the best of this also. The country had lost its headway and was thoroughly at the mercy of events.

When studied as a mere matter of political philosophy, it is clear enough that this painful period of paralysis was an inevitable stage in the national development. The party which had come into power in 1801 held theories inconsistent with thorough nationality, and, as a consequence, with a firm foreign policy. The terrible treatment which the government received, while in its hands, from the great military powers of Europe came upon the Republican party before it had outgrown its theories, and necessarily disorganized that party, leaving the old States-rights, anti-nationalizing element where it stood, and forcing the more malleable element forward into a situation inconsistent with the party tenets. Another result was to give the mere camp-followers and mercenaries of both parties an almost unlimited power of mischief. Finally, the Federalist opposition, affected in the same manner by the same causes, also rapidly resolved itself into three similar elements, one of which seriously meditated treason, while the more liberal one maintained a national character. It was clear, therefore, or rather it is now clear, that until the sentiment of nationality became strong enough to override resistance and to carry the Administration on its shoulders, no effective direction could be given to government.

That Mr. Gallatin consciously and decidedly followed either direction, it would be a mistake to suppose. He too, like his party, was torn by conflicting influences. A man already fifty years old, whose life has been earnestly and arduously devoted to certain well-defined objects that have always in his eyes stood for moral principles, cannot throw those objects away without feeling that his life goes with them. So long as a reasonable hope was left of attaining the results he had aimed at, or of preventing the dangers he dreaded, it was natural that Mr. Gallatin should cling to it and fight for it; but, on the other hand, he was a man of very sound understanding, and little, if at all, affected by mere local prejudices; his ideal government was one which should be free from corruption and violence; which should interfere little with the individual; which should have neither debt, nor army, nor navy, nor taxes, beyond what its simplest wants required; and which should wish “to become a happy, and not a powerful, nation, or at least no way powerful except for self-defence.” On this side he was in sympathy with all moderate and sensible men in both parties, and was more naturally impelled to act with them than with his old allies, who were chiefly jealous of national power because it diminished the sovereignty of Virginia or South Carolina.