полная версия

полная версияTalkers: With Illustrations

You would do well to study the lesson, When to talk, and when to be silent. Silence is preferred by the wise and the good to superfluity of talking. You may read strange stories of some of the ancients, choosing silence to talking. St. Romualdus maintained a seven years’ silence on the Syrian mountains. It is said of a religious person in a monastery in Brabant, that he did not speak a word in sixteen years. Ammona lived with three thousand brethren in such silence as though he was an anchoret. Theona was silent for thirty years together. Johannes, surnamed Silentarius, was silent for forty-seven years. I do not mention these as examples for your imitation, and would not have you become such a recluse. These are cases of an extreme kind, – cases of moroseness and sullenness which neither reason nor Scripture justify. “This was,” as Taylor observes, “to make amends for committing many sins by omitting many duties; and, instead of digging out the offending eye, to pluck out both, that they might neither see the scandal nor the duty; for fear of seeing what they should not, to shut their eyes against all light.” The wiser course for you to adopt is the practice of silence for a time, as a discipline for the correction of the fault into which you have fallen. Pray as did the Psalmist, “Put a guard, O Lord, unto my mouth, and a door unto my lips.” “He did not ask for a wall,” as St. Gregory remarks, “but for a door, a door that might open and shut.” It is said of Cicero, he never spake a word which himself would fain have recalled; he spake nothing that repented him. Silence will be a cover to your folly, and a disclosure of your wisdom.

“Keep thy lips with all diligence.”

“A man that speaketh too much, and museth but little and lightly,Wasteth his mind in words, and is counted a fool among men:But thou when thou hast thought, weave charily the web of meditation,And clothe the ideal spirit in the suitable garments of speech.”Note well the discretion of silence. What man ever involved himself in difficulties through silence? Who thinks another a fool because he does not talk? Keep quiet, and you may be looked upon as a wise man; open your mouth and all may see at once that you are a simpleton. Ben Jonson, speaking of one who was taken for a man of judgment while he was silent, says, “This man might have been a Counsellor of State, till he spoke; but having spoken, not the beadle of the ward.”

Lord Lytton tells of a groom who married a rich lady, and was in fear as to how he might be treated by the guests of his new household, on the score of his origin and knowledge: to whom a clergyman gave this advice, “Wear a black coat, and hold your tongue.” The groom acted on the advice, and was considered a gentlemanly and wise man.

The same author speaks of a man of “weighty name,” with whom he once met, but of whom he could make nothing in conversation. A few days after, a gentleman spoke to him about this “superior man,” when he received for a reply, “Well, I don’t think much of him. I spent the other day with him, and found him insufferably dull.” “Indeed,” said the gentleman, with surprise; “why, then I see how it is: Lord – has been positively talking to you.”

This reminds one of the story told of Coleridge. He was once sitting at a dinner-table admiring a fellow guest opposite as a wise man, keeping himself in solemn and stately reserve, and resisting all inducements to join in the conversation of the occasion, until there was placed on the table a steaming dish of apple-dumplings, when the first sight of them broke the seal of the wise man’s intelligence, exclaiming with enthusiasm, “Them be the jockeys for me.”

Gay, in his fables, addressing himself to one of these talkers, says, —

“Had not thy forward, noisy tongueProclaim’d thee always in the wrong,Thou might’st have mingled with the rest,And ne’er thy foolish sense confess’d;But fools, to talking ever prone,Are sure to make their follies known.”Mr. Monopolist, can you refrain a little longer while I say a few more words? I have in my possession several recipes for the cure of much talking, that I have gathered in the course of my reading, four of which I will kindly lay before you for consideration.

1. Give yourself to private writing; and thus pour out by the hand the floods which may drown the head. If the humour for much talking was partly drawn forth in this way, that which remained would be sufficient to drop out from the tongue.

2. In company with your superiors in wisdom, gravity, and circumstances, restrain your unreasonable indulgence of the talking faculty. It is thought this might promote modest and becoming silence on all other occasions. “One of the gods is within,” said Telemachus; upon occasion of which his father reproved his talking. “Be thou silent and say little; let thy soul be in thy hand, and under command; for this is the rite of the gods above.”

3. Read and ponder the words of Solomon, “He that hath knowledge spareth his words; and a man of understanding is of excellent spirit. Even a fool when he holdeth his peace is counted wise: and he that shutteth his lips is esteemed a man of understanding” (Prov. xvii. 27, 28). Also the words of the Son of Sirach, “Be swift to hear, and if thou hast understanding, answer thy neighbour; if not, lay thy hand upon thy mouth. A wise man will hold his tongue till he see opportunity; but a babbler and a fool will regard no time. He that useth many words shall be abhorred; and he that taketh to himself authority therein shall be hated” (Ecclesiasticus v. 11-13). “In the multitude of words there wanteth not sin” (Prov. x. 19).

4. Attend more to business and action. It is thought that a diligent use of the muscles in physical labour may detract from the disposition, time, and power of excessive speech. Paul gives a similar suggestion, “And that ye study to be quiet, and to do your own business, and to work with your own hands as we commanded you” (1 Thes. iv. 11).

With these few words of advice I now leave you, my friend Monopolist, hoping they may have their due effect upon your talking faculty, and that when I meet you again in company I shall find you a “new edition, much amended and abridged:” “the half better than the whole.”

II.

THE FALSE HUMOURIST

“There are more faults in the humour than in the mind.”

– La Rochefoucauld.Among the various kinds of talk there is, perhaps, none in which talkers are more liable to fail than in humour. It is that in which most persons like to excel, but which comparatively few attain. It is not the man whose imagination teems with monsters, whose head is filled with extravagant conceptions, that furnishes innocent pleasure by humour. And yet there are those who claim to be humourists, whose humour consists only in wild irregular fancies and distortions of thought. They speak nonsense, and think they are speaking humour. When they have put together a round of absurd, inconsistent ideas, and produce them, they cannot do it without laughing. I have sometimes met with a portion of this class that have endeavoured to gain themselves the reputation of wits and humourists by such monstrous conceits as almost qualified them for Bedlam, rather than refined and intelligent society. They did not consider that humour should always lie under the check of reason; and requires the direction of the nicest judgment, by so much the more it indulges in unrestrained freedoms. There is a kind of nature in this sort of conversation, as well as in other; and a certain regularity of thought which must discover the speaker to be a man of sense, at the same time he appears a man given up to caprice. For my part, when I hear the delirious mirth of an unskilful talker, I cannot be so barbarous as to divert myself with it, but am rather apt to pity the man than laugh at anything he speaks.

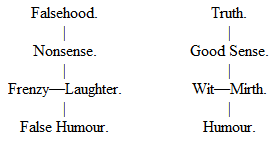

“It is indeed much easier,” says Addison, “to describe what is not humour than what is; and very difficult to define it otherwise than as Cowley has done wit, by negatives. Were I to give my own notions of it, I would deliver them after Plato’s manner, in a kind of allegory – and by supposing humour to be a person, deduce to him all his qualifications, according to the following genealogy. Truth was the founder of the family, and the father of Good Sense. Good Sense was the father of Wit, who married a lady of collateral line called Mirth, by whom he had issue, Humour. Humour, therefore, being the youngest of this illustrious family, and descendant from parents of such different dispositions, is very various and unequal in his temper: sometimes you see him putting on grave looks and a solemn habit, sometimes airy in his behaviour, and fantastic in his dress; inasmuch that at different times he appears as serious as a judge, and as jocular as a merry-andrew. But as he has a great deal of the mother in his constitution, whatever mood he is in, he never fails to make his company laugh.”

In carrying on the allegory farther, he says of the false humourists, “But since there is an impostor abroad, who takes upon him the name of this young gentleman, and would willingly pass for him in the world: to the end that well-meaning persons may not be imposed upon by cheats, I would desire my readers, when they meet with this pretender, to look into his parentage and examine him strictly, whether or no he be remotely allied to truth, and lineally descended from good sense; if not, they may conclude him a counterfeit. They may likewise distinguish him by a loud and excessive laughter, in which he seldom gets his company to join with him. For as true Humour generally looks serious, while everybody laughs about him; false Humour is always laughing, while everybody about him looks serious. I shall only add, if he has not in him a mixture of both parents, that is, if he would pass for the offspring of Wit without Mirth, or Mirth without Wit, you may conclude him to be altogether spurious and a cheat.

The impostor of whom I am speaking descends originally from Falsehood, who was the mother of Nonsense, who gave birth to a son called Frenzy, who married one of the daughters of Folly, commonly known by the name of Laughter, from whom came that monstrous infant of which I have been speaking. I shall set down at length the genealogical table of False Humour, and, at the same time, place by its side the genealogy of True Humour, that the reader may at one view behold their different pedigree and relations: —

I might extend the allegory, by mentioning several of the children of False Humour, who are more in number than the sands of the sea, and might in particular enumerate the many sons and daughters of which he is the actual parent. But as this would be a very invidious task, I shall only observe in general that False Humour differs from the True, as a monkey does from a man.

First of all, he is exceedingly given to little apish tricks and buffooneries.

Secondly, he so much delights in mimicry, that it is all one to him whether he exposes by it vice and folly, luxury and avarice; or, on the contrary, virtue and wisdom, pain and poverty.

Thirdly, he is wonderfully unlucky, inasmuch that he will bite the hand that feeds him, and endeavour to ridicule both friends and foes indifferently. For, having but small talents, he must be merry where he can, not where he should.

Fourthly, being entirely devoid of reason, he pursues no point either of morality or instruction, but is ludicrous only for the sake of being so.”

III.

THE FLATTERER

“Who flatters is of all mankind the lowest,Save him who courts the flattery.”Hannah More.The Flatterer is a false friend clothed in the garb of a true one. He speaks words from a foul heart through fair lips. His eyes affect to see only beauty and perfection, and his tongue pours out streams of sparkling praises. He is enamoured of your appearance, and your general character commands his admiration. You have no fault which he may correct, or delinquency which he may rebuke. The last time he met you in company, your manners pleased him beyond measure; and though you saw it not, yet he observed how all eyes were brightened by seeing you. If you occupy a position of authority whence you can bestow a favour which he requires, you are “most gracious, powerful, and good.” His titles are all in the superlative, and his addresses full of wondering interjections. His object is more to please than to speak the truth. His art is nothing but delightful trickery by means of smoothing words and complacent looks. He would make men fools by teaching them to overrate their abilities. Those who walk in the vale of humility amid the modest flowers of virtue and favoured with the presence of the Holy One, he would lift into the Utopian heights of vanity and pride, that they might fall into the condemnation of the Devil. He gathers all good opinions and approving sentiments that he might carry them to his prey, losing nothing in weight and number during their transit. He is one of Fame’s best friends, helping to furnish her with some of her strongest and richest rumours. But conscience has not a greater adversary; for when it comes forth to do its office in accusation or reproof, he anticipates its work, and bribes her with flattering speech. Like the chamelion, he changes his appearance to suit his purpose. He sometimes affects to be nothing but what pleases the object of his admiration, whose virtues he applauds and whose imperfections he pretends it to be an advantage to imitate. When he walks with his friend, he would feign have him believe that every eye looks at him with interest, and every tongue talks of him with praise – that he to whom he deigns to give his respects is graced with peculiar honour. He tells him he knows not his own worth, lest he should be too happy or vain; and when he informs him of the good opinions of others, with a mock-modesty he interrupts himself in the relation, saying he must not say any more lest he be considered to flatter, making his concealment more insinuating than his speech. He approaches with fictitious humility to the creature of his praise, and hangs with rivetted attention upon his lips, as though he spake with the voice of an oracle. He repeats what phrase or sentence may particularly gratify him, and both hands are little enough to bless him in return. Sometimes he extols the excellencies of his friend in his absence, but it is in the presence of those who he is pretty certain will convey it to his ears. In company, he sometimes whispers his commendations to the one next him, in such a way that his friend may hear him in the other part of the room.

The Flatterer is a talker who insinuates himself into every circle; and there are few but are fond of his fair speech and gaudy praise. He conceals himself with such dexterousness that few recognise him in his true character. Those with whom he has to do too frequently view him as a friend, and confide in his communications. What door is not open to the man who brings the ceremonious compliments of praise in buttery lips and sugared words – who carries in his hand a bouquet of flowers, and in his face the complacent smile, addressing you in words which feed the craving of vanity, and yet withal seem words of sincere friendship and sound judgment?

Where is the man who has the moral courage, the self-abnegation to throw back honied encomiums which come with apparent reality, although from a flatterer? “To tell a man that he cannot be flattered is to flatter him most effectually.”

“Honey’d assent,How pleasant art thou to the taste of man,And woman also! flattery directRarely disgusts. They little know mankindWho doubt its operation: ’tis my key,And opes the wicket of the human heart.”“The firmest purpose of a human heartTo well-tim’d artful flattery may yield.”“’Tis an old maxim in the schoolsThat flattery’s the food of fools;Yet now and then your men of witWill condescend to take a bit.”The Flatterer is a lurking foe, a dangerous friend, a subtle destroyer. “A flattering mouth worketh ruin.” “He that speaketh flattery to his friends, even the eyes of his children shall fail.” “A man that flattereth his neighbour spreadeth a net for his feet.” The melancholy results of flattery are patent before the world, both on the page of history and in the experience of mankind. How many thousand young men who once stood in the uprightness of virtue are now debased and ruined through the flattery of the “strange woman,” so graphically described by Solomon in Prov. vii., “With her much fair speech she caused him to yield, with the flattering of her lips she forced him. He goeth after her straightway, as an ox goeth to the slaughter, or as a fool to the correction of the stocks; till a dart strike through his liver; as a bird hasteth to the snare, and knoweth not that it is for his life” (vers. 21-23). “She hath cast down many wounded: yea, many strong men have been slain by her. Her house is the way to hell, going down to the chambers of death” (vers. 26, 27).

And as the virtuous young man is thus led into ruin by the flattering tongue of the strange woman; so the virtuous young female is sometimes led into ruin by the flattering tongue of the lurking enemy of beauty and innocence. I cannot give a more striking and pathetic illustration of this than the one portrayed by the incomparable hand of Pollok: —

“Take one example, one of female woe.Loved by her father, and a mother’s love,In rural peace she lived, so fair, so lightOf heart, so good and young, that reason scarceThe eye could credit, but would doubt, as sheDid stoop to pull the lily or the roseFrom morning’s dew, if it realityOf flesh and blood, or holy vision, saw,In imagery of perfect womanhood.But short her bloom – her happiness was short.One saw her loveliness, and with desireUnhallowed, burning, to her ear addressedDishonest words: ‘Her favour was his life,His heaven; her frown his woe, his night, his death.’With turgid phrase thus wove in flattery’s loom,He on her womanish nature won, and ageSuspicionless, and ruined and forsook:For he a chosen villain was at heart,And capable of deeds that durst not seekRepentance. Soon her father saw her shame;His heart grew stone; he drove her forth to wantAnd wintry winds, and with a horrid cursePursued her ear, forbidding her return.Upon a hoary cliff that watched the sea,Her babe was found – dead; on its little cheek,The tear that nature bade it weep had turnedAn ice-drop, sparkling in the morning beam;And to the turf its helpless hands were frozen:For she, the woeful mother, had gone mad,And laid it down, regardless of its fateAnd of her own. Yet had she many daysOf sorrow in the world, but never wept.She lived on alms; and carried in her handSome withering stalks, she gathered in the spring;When they asked the cause, she smiled, and said,They were her sisters, and would come and watchHer grave when she was dead. She never spokeOf her deceiver, father, mother, home,Or child, or heaven, or hell, or God; but stillIn lonely places walked, and ever gazedUpon the withered stalks, and talked to them;Till wasted to the shadow of her youth,With woe too wide to see beyond – she died;Not unatoned for by imputed blood,Nor by the Spirit that mysterious works,Unsanctified. Aloud her father cursedThat day his guilty pride which would not ownA daughter whom the God of heaven and earthWas not ashamed to call His own; and heWho ruined her read from her holy look,That pierced him with perdition manifold,His sentence, burning with vindictive fire.”The flattering talker possesses a power which turned angels into devils, and men into demons – which beguiled pristine innocence and introduced the curse – which has made half the world crazy with self-esteem and self-admiration. A power which has dethroned princes, involved kingdoms, degraded the noble, humbled the great, impoverished the rich, enslaved the free, polluted the pure, robbed the wise man of his wisdom, the strong man of his strength, the good man of his goodness. It is emphatically the power of the Destroyer, working havoc, devastation, woe, and death wherever it has sway, spreading disappointment, weeping, lamentation, and broken hearts through the habitations of the children of men. “He is,” as an old writer quaintly observes, “the moth of liberal men’s coats, the ear-wig of the mighty, the bane of courts, a friend and slave to the trencher, and good for nothing but to be a factor for the devil.”

Mr. Sharp was a young student of amiable spirit, and promising abilities. Soon after he left college he took charge of an important church in the large village of C – , in the county of M – . He had not been long among his people before he won the good-will of all; and his popularity soon extended beyond the pale of his own church. Meantime, he did not appear to think of himself more than he ought. He was unassuming in his spirit, and devoted to his work, apparently non-affected by the general favour with which he was received.

There was a member of his church whom we shall call Mr. Thoughtless; a man of good education, respectable intelligence, and in circumstances of moderate wealth. He was in the church an officer of considerable importance and weight. He was, however, given to the use of soft words, and complimentary speeches. In fact, he was a flatterer. He used little or no wisdom in his flattery, but generally poured it forth in fulsome measure upon all whom he regarded his friends. Mr. Sharp was a particular favourite with him, and he frequently invited him to his house. He did not observe the failing of his host, but considered him a very kind man, sweet-tempered, one of his best friends, the only member of his Church from whom he received any encouragement in his ministerial labours. Mr. Sharp became increasingly attached to him, and passed the greater part of his leisure hours in his company. The fact was, Mr. Thoughtless did not restrain his expressions of “great satisfaction” and “strong pleasure” in the “character and abilities” of Mr. Sharp. He was the “best minister ever among them” – “every one admired him” – “what a splendid sermon he preached last Sabbath morning” – “the congregations were doubled since he came” – he was “delighted with his general demeanour” – he “really thought his abilities were adequate to a larger Church in a city, than theirs in the country” – but he must not be “considered in speaking these things to flatter, for he should be ashamed to say anything to flatter a young minister whom he esteemed so highly,” and besides, he “thought him beyond the power of flattery.” Such were the flattering words which he poured into the undiscerning mind of Mr. Sharp at different times.

Not long after this close friendship and these frequent visits, Mr. Sharp began to manifest a change in his spirit and conduct, which gradually developed into such proportions that some of the Church could not help noticing it.

“I do not think,” said Mr. Smith – a truly godly man – to Mrs. Lane – who also was in repute for her piety – one day in conversation, “that our young pastor is so unassuming and devoted as when he first came among us.”

“Is it not all fancy on your part, Mr. Smith?” asked Mrs. Lane.

“I only hope it may be, but I fear it is true.”

“In what respects do you think he is changed?” asked Mrs. Lane.

“I do not, somehow or other, observe the same tone of spirituality in his preaching and company as were so obvious during the first part of his sojourn with us.”

“Well, do you know,” said Mrs. Lane, “although I asked whether it was not all fancy on your part, yet I have had my apprehensions and fears, similar to yours. I have never mentioned them to any one before. I have been very grieved to see the change, and have prayed much for him. How do you account for it, Mr. Smith?”

“I can only account for it by the supposition that he has been too much under the influence of Mr. Thoughtless, who, you know, is a man given to flattery, and who has by this flattery injured other young ministers who have been with us.”

“It is ten thousand pities,” said Mrs. Lane, “that Mr. Sharp was not warned of the dangers of his flattery.”

“It is just here, you know, Mrs. Lane. Mr. Thoughtless is a man of such influence in our Church, so bland in his way, so fair in his words, so wealthy in his means, that it is little use saying anything to warn against him. Besides, I fear that others have been too flattering in their addresses and compliments.”