полная версия

полная версияThe Arawack Language of Guiana in its Linguistic and Ethnological Relations

As it is thus rendered extremely probable that the Arawack is closely connected with the great linguistic families of South America, it becomes of prime importance to trace its extension northward, and to determine if it is in any way affined to the tongues spoken on the West India Islands, when these were first discovered.

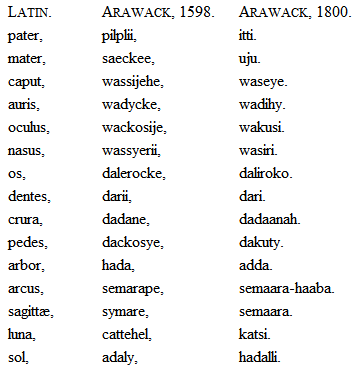

The Arawacks of to-day when asked concerning their origin point to the north, and claim at some not very remote time to have lived at Kairi, an island, by which generic name they mean Trinidad. This tradition is in a measure proved correct by the narrative of Sir Walter Raleigh, who found them living there in 1595,10 and by the Belgian explorers who in 1598 collected a short vocabulary of their tongue. This oldest monument of the language has sufficient interest to deserve copying and comparing with the modern dialect. It is as follows:

The syllables wa our, and da my, prefixed to the parts of the human body, will readily be recognized. When it is remembered that the dialect of Trinidad no doubt differed slightly from that on the mainland; that the modern orthography is German and that of De Lact’s list is Dutch; and that two centuries intervened between the first and second, it is really a matter of surprise to discover such a close similarity. Father and mother, the only two words which are not identical, are doubtless different expressions, relationship in this, as in most native tongues, being indicated with excessive minuteness.

The chain of islands which extend from Trinidad to Porto Rico were called, from their inhabitants, the Caribby islands. The Caribs, however, made no pretence to have occupied them for any great length of time. They distinctly remembered that a generation or two back they had reached them from the mainland, and had found them occupied by a peaceful race, whom they styled Ineri or Igneri. The males of this race they slew or drove into the interior, but the women they seized for their own use. Hence arose a marked difference between the languages of the island Caribs and their women. The fragments of the language of the latter show clearly that they were of Arawack lineage, and that the so-called Igneri were members of that nation. It of course became more or less corrupted by the introduction of Carib words and forms, so that in 1674 the missionary De la Borde wrote, that “although there is some difference between the dialects of the men and women, they readily understand each other;”11 and Father Breton in his Carib Grammar (1665) gives the same forms for the declensions and conjugations of both.

As the traces of the “island Arawack,” as the tongue of the Igneri may be called, prove the extension of this tribe over all the Lesser Antilles, it now remains to inquire whether they had pushed their conquests still further, and had possessed themselves of the Great Antilles, the Bahama islands, and any part of the adjacent coasts of Yucatan or Florida.

All ancient writers agree that on the Bahamas and Cuba the same speech prevailed, except Gomara, who avers that on the Bahamas “great diversity of language” was found.12 But as Gomara wrote nearly half a century after those islands were depopulated, and has exposed himself to just censure for carelessness in his statements regarding the natives,13 his expression has no weight. Columbus repeatedly states that all the islands had one language though differing, more or less, in words. The natives he took with him from San Salvador understood the dialects in both Cuba and Haiti. One of them on his second voyage served him as an interpreter on the southern shore of Cuba.14

In Haiti, there was a tongue current all over the island, called by the Spaniards la lengua universal and la lengua cortesana. This is distinctly said by all the historians to have been but very slightly different from that of Cuba, a mere dialectic variation in accent being observed.15 Many fragments of this tongue are preserved in the narratives of the early explorers, and it has been the theme for some strange and wild theorizing among would-be philologists. Rafinesque christened it the “Taino” language, and discovered it to be closely akin to the “Pelasgic” of Europe.16 The Abbé Brasseur de Bourbourg will have it allied to the Maya, the old Norse or Scandinavian, the ancient Coptic, and what not. Rafinesque and Jegor von Sivors17 have made vocabularies of it, but the former in so uncritical, and the latter in so superficial a manner, that they are worse than useless.

Although it is said there were in Haiti two other tongues in the small contiguous provinces of Macorix de arriba and Macorix de abajo, entirely dissimilar from the lengua universal and from each other, we are justified in assuming that the prevalent tongue throughout the whole of the Great Antilles and the Bahamas, was that most common in Haiti. I have, therefore, perused with care all the early authorities who throw any light upon the construction and vocabulary of this language, and gathered from their pages the scattered information they contain. The most valuable of these authorities are Peter Martyr de Angleria, who speaks from conversations with natives brought to Spain by Columbus, on his first voyage,18 and who was himself, a fine linguist, and Bartolomé de las Casas. The latter came as a missionary to Haiti, a few years after its discovery, was earnestly interested in the natives, and to some extent acquainted with their language. Besides a few printed works of small importance, Las Casas left two large and valuable works in manuscript, the Historia General de las Indias Occidentales, and the Historia Apologetica de las Indias Occidentals. A copy of these, each in four large folio volumes, exists in the Library of Congress, where I consulted them. They contain a vast amount of information relating to the aborigines, especially the Historia Apologetica, though much of the author’s space is occupied with frivolous discussions and idle comparisons.

In later times, the scholar who has most carefully examined the relics of this ancient tongue, is Señor Don Estevan Richardo, a native of Haiti, but who for many years resided in Cuba. His views are contained in the preface to his Diccionario Provincial casi-razonado de Voces Cubanas, (Habana, 2da ed, 1849). He has found very many words of the ancient language retained in the provincial Spanish of the island, but of course in a corrupt form. In the vocabulary which I have prepared for the purpose of comparison, I have omitted all such corrupted forms, and nearly all names of plants and animals, as it is impossible to identify these with certainty, and in order to obtain greater accuracy, have used, when possible, the first edition of the authors quoted, and in most instances, given under each word a reference to some original authority.

From the various sources which I have examined, the alphabet of the lengua universal appears to have been as follows: a, b, d, e, (rarely used at the commencement of a word), g, j, (an aspirated guttural like the Catalan j, or as Peter Martyr says, like the Arabic ch), i (rare), l (rare), m, n, o (rare,) p, q, r, s, t, u, y. These letters, it will be remembered, are as in Spanish.

The Spanish sounds z, ce, ci (English th,) ll, and v, were entirely unknown to the natives, and where they appear in indigenous words, were falsely written for l and b. The Spaniards also frequently distorted the native names by writing x for j, s, and z, by giving j the sound of the Latin y, and by confounding h, j, and f, as the old writers frequently employ the h to designate the spiritus asper, whereas in modern Spanish it is mute.19

Peter Martyr found that he could reduce all the words of their language to writing, by means of the Latin letters without difficulty, except in the single instance of the guttural j. He, and all others who heard it spoken, describe it as “soft and not less liquid than the Latin,” “rich in vowels and pleasant to the ear,” an idiom “simple, sweet, and sonorous.”20

In the following vocabulary I have not altered in the least the Spanish orthography of the words, and so that the analogy of many of them might at once be preceived, I have inserted the corresponding Arawack expression, which, it must be borne in mind, is to be pronounced by the German alphabet.

Vocabulary of the Ancient Language of the Great Antilles

Aji, red pepper. Arawack, achi, red pepper.

Aon, dog (Las Casas, Hist. Gen. lib. I, c. 120). Island Ar. ánli, dog.

Arcabuco, a wood, a spot covered with trees (Oviedo, Hist. Gen. de las Indias, lib. VI, c, 8). Ar. arragkaragkadin the swaying to and fro of trees.

Areito, a song chanted alternately by the priests and the people at their feasts. (Oviedo, Hist. Gen. lib. V, c. 1.) Ar. aririn to name, rehearse.

Bagua, the sea. Ar. bara, the sea.

Bajaraque, a large house holding several hundred persons. From this comes Sp. barraca, Eng. barracks. Ar. bajü, a house.

Bajari, title applied to sub-chiefs ruling villages, (Las Casas, Hist. Apol. cap. 120). Probably “house-ruler,” from Ar. bajü, house.

Barbacoa, a loft for drying maize, (Oviedo, Hist. Gen. lib. VII, cap. 1). From this the English barbacue. Ar. barrabakoa, a place for storing provisions.

Batay, a ball-ground; bates, the ball; batey, the game. (Las Casas, Hist. Apol. c. 204). Ar. battatan, to be round, spherical.21

Batea, a trough. (Las Casas, Hist. Apol. c. 241.)

Bejique, a priest. Ar. piaye, a priest.

Bixa, an ointment. (Las Casas, Hist. Apol. cap. 241.)

Cai, cayo, or cayco, an island. From this the Sp. cayo, Eng. key, in the “Florida keys.” Ar. kairi, an island.

Caiman, an alligator, Ar. kaiman, an alligator, lit. to be strong.

Caona or cáuni, gold. (Pet. Martyr, Decad. p. 26, Ed. Colon, 1564). Ar. kaijaunan, to be precious, costly.

Caracol, a conch, a univalve shell. From this the Sp. caracol. (Richardo, Dicc. Provin. s. v). Probably from Galibi caracoulis, trifles, ornaments. (See Martius, Sprachenkunde, B. II, p. 332.)

Caney or cansi, a house of conical shape.

Canoa, a boat. From this Eng. canoe. Ar. kannoa, a boat.

Casique, a chief. This word was afterwards applied by Spanish writers to the native rulers throughout the New World. Ar. kassiquan (from ussequa, house), to have or own a house or houses; equivalent, therefore, to the Eng. landlord.

Cimu or simu, the front, forehead; a beginning. (Pet. Martyr, Decad. p. 302.) Ar. eme or uime, the mouth of a river, uimelian, to be new.

Coaibai, the abode of the dead.

Cohóba, the native name of tobacco.

Conuco, a cultivated field. (Oviedo, Hist. Gen. lib. VII, cap. 2.)

Duhos or duohos, low seats (unas baxas sillas, Las Casas, Hist. Gen. lib. I, cap 96. Oviedo, Hist. Gen. lib. V. cap. 1. Richardo, sub voce, by a careless reading of Oviedo says it means images). Ar. dulluhu or durruhu, a seat, a bench.

Goeiz, the spirit of the living (Pane, p. 444); probably a corruption of Guayzas. Ar. akkuyaha, the spirit of a living animal.

Gua, a very frequent prefix: Peter Martyr says, “Est apud eos articulus et pauca sunt regum praecipue nominum quae non incipiant ab hoc articulo gua.” (Decad. p. 285.) Very many proper names in Cuba and Hayti still retain it. The modern Cubans pronounce it like the English w with the spiritus lenis. It is often written oa, ua, oua, and hua. It is not an article, but corresponds to the ah in the Maya, and the gue in the Tupi of Brazil, from which latter it is probably derived.22

Guaca, a vault for storing provisions.

Guacabiua, provisions for a journey, supplies.

Guacamayo, a species of parrot, macrocercus tricolor.

Guanara, a retired stop. (Pane, p. 444); a species of dove, columba zenaida (Richardo, S. V.)

Guanin, an impure sort of gold.

Guaoxeri, a term applied to the lowest class of the inhabitants (Las Casas, Hist. Apol. cap. 197.) Ar. wakaijaru, worthless, dirty, wakaijatti lihi, a worthless fellow.

Guatiao, friend, companion (Richardo). Ar. ahati, companion, playmate.

Guayzas, masks or figures (Las Casas, Hist. Apol. cap. 61). Ar. akkuyaha, living beings.

Haba, a basket (Las Casas, Hist. Gen. lib. III, cap. 21). Ar. habba, a basket.

Haiti, stony, rocky, rough (Pet. Martyr, Decades). Ar. aessi or aetti, a stone.

Hamaca, a bed, hammock. Ar. hamaha, a bed, hammock.

Hico, a rope, ropes (Oviedo, Hist. Gen. lib. V, cap. 2).

Hobin, gold, brass, any reddish metal. (Navarrete Viages, I, p. 134, Pet. Martyr, Dec. p. 303). Ar. hobin, red.

Huiho, height. (Pet. Martyr, p. 304). Ar. aijumün, above, high up.

Huracan, a hurricane. From this Sp. huracan, Fr. ouragan, German Orkan, Eng. hurricane. This word is given in the Livre Sacré des Quichès as the name of their highest divinity, but the resemblance may be accidental. Father Ximenes, who translated the Livre Sacrè, derives the name from the Quiché hu rakan, one foot. Father Thomas Coto, in his Cakchiquel Dictionary, (MS. in the library of the Am. Phil. Soc.) translates diablo by hurakan, but as the equivalent of the Spanish huracan, he gives ratinchet.

Hyen, a poisonous liquor expressed from the cassava root. (Las Casas, Hist. Apol. cap. 2).

Itabo, a lagoon, pond. (Richardo).

Juanna, a serpent. (Pet. Martyr, p. 63). Ar. joanna, a lizard; jawanaria, a serpent.

Macana, a war club. (Navarrete, Viages. I, p. 135).

Magua, a plain. (Las Casas, Breviss. Relat. p. 7).

Maguey, a native drum. (Pet. Martyr, p. 280).

Maisi, maize. From this Eng. maize, Sp. mais, Ar. marisi, maize.

Matum, liberal, noble. (Pet. Martyr, p. 292).

Matunheri, a title applied to the highest chiefs. (Las Casas, Hist. Apol. cap. 197).

Mayani, of no value, (“nihili,” Pet. Martyr, p. 9). Ar. ma, no, not.

Naborias, servants. (Las Casas, Hist. Gen. lib. III, cap. 32).

Nacan, middle, center. Ar. annakan, center.

Nagua, or enagua, the breech cloth made of cotton and worn around the middle. Ar. annaka, the middle.

Nitainos, the title applied to the petty chiefs, (regillos ò guiallos, Las Casas, Hist. Apol. cap, 197); tayno vir bonus, taynos nobiles, says Pet. Martyr, (Decad. p. 25). The latter truncated form of the word was adopted by Rafinesque and others, as a general name for the people and language of Hayti. There is not the slightest authority for this, nor for supposing, with Von Martius, that the first syllable is a pronominal prefix. The derivation is undoubtedly Ar. nüddan to look well, to stand firm, to do anything well or skilfully.

Nucay or nozay, gold, used especially in Cuba and on the Bahamas. The words caona and tuob were in vogue in Haiti (Navarrete, Viages, Tom. 1, pp. 45, 134).

Operito, dead, and

Opia, the spirit of the dead (Pane, pp. 443, 444). Ar. aparrün to kill, apparahun dead, lupparrükittoa he is dead.

Quisquéia, a native name of Haiti; “vastitas et universus ac totus. Uti Græci suum Panem,” says Pet. Martyr (Decad. p. 279). “Madre de las tierras,” Valverde translates it (Idea del valor de la Isla Espanola, Introd. p. xviii). The orthography is evidently very false.

Sabana, a plain covered with grass without trees (terrano llano, Oviedo, Hist. Gen. lib. vi. cap. 8). From this the Sp. savana, Eng. savannah. Charlevoix, on the authority of Mariana, says it is an ancient Gothic word (Histoire de l’Isle St. Domingue, i. p. 53). But it is probably from the Ar. sallaban, smooth, level.

Semi, the divinities worshipped by the natives (“Lo mismo que nosotros llamamos Diablo,” Oviedo, Hist. Gen. lib. v. cap. 1. Not evil spirits only, but all spirits). Ar. semeti sorcerers, diviners, priests.

Siba, a stone. Ar. siba, a stone.

Starei, shining, glowing (relucens, Pet. Martyr, Decad. p. 304). Ar. terén to be hot, glowing, terehü heat.

Tabaco, the pipe used in smoking the cohoba. This word has been applied in all European languages to the plant nicotiana tabacum itself.

Taita, father (Richardo). Ar. itta father, daitta or datti my father.

Taguáguas, ornaments for the ears hammered from native gold (Las Casas, Hist. Apol. cap. 199).

Tuob, gold, probably akin to hobin, q. v.

Turey, heaven. Idols were called “cosas de turey” (Navarrete, Viages, Tom. i. p. 221). Probably akin to starei, q. v.

The following numerals are given by Las Casas (Hist. Apol. cap. 204).

1 hequeti. Ar. hürketai, that is one, from hürkün to be single or alone.

2 yamosa. Ar. biama, two.

3 canocum. Ar. kannikún, many, a large number, kannikukade, he has many things.

4 yamoncobre, evidently formed from yamosa, as Ar. bibiti, four, from biama, two.

The other numerals Las Casas had unfortunately forgotten, but he says they counted by hands and feet, just as the Arawacks do to this day.

Various compound words and phrases are found in different writers, some of which are readily explained from the Arawack. Thus tureigua hobin, which Peter Martyr translates “rex resplendens uti orichalcum,”23 in Arawack means “shining like something red.” Oviedo says that at marriages in Cuba it was customary for the bride to bestow her favors on every man present of equal rank with her husband before the latter’s turn came. When all had thus enjoyed her, she ran through the crowd of guests shouting manícato, manícato, “lauding herself, meaning that she was strong, and brave, and equal to much.”24 This is evidently the Ar. manikade, from mân, manin, and means I am unhurt, I am unconquered. When the natives of Haiti were angry, says Las Casas,25 they would not strike each other, but apply such harmless epithets as buticaco, you are blue-eyed (anda para zarco de los ojos), xeyticaco, you are black-eyed (anda para negro de los ojos), or mahite, you have lost a tooth, as the case might be. The termination aco in the first two of these expressions is clearly the Ar. acou, or akusi, eyes, and the last mentioned is not unlike the Ar. márikata, you have no teeth (ma negative, ari tooth). The same writer gives for “I do not know,” the word ita, in Ar. daitta.26

Some of the words and phrases I have been unable to identify in the Arawack. They are duiheyniquen, dives fluvius, maguacochíos vestiti homines, both in Peter Martyr, and the following conversation, which he says took place between one of the Haitian chieftians and his wife.

She. Teítoca teítoca. Técheta cynáto guamechyna. Guaibbá.

He. Cynáto machabuca guamechyna.

These words he translated: teitoca be quiet, técheta much, cynato angry, guamechyna the Lord, guaibba go, machabuca what is it to me. But they are either very incorrectly spelled, or are not Arawack.

The proper names of localities in Cuba, Hayti and the Bahamas, furnish additional evidence that their original inhabitants were Arawacks. Hayti, I have already shown has now the same meaning in Arawack which Peter Martyr ascribed to it at the discovery. Cubanacan, a province in the interior of Cuba, is compounded of kuba and annakan, in the center;27 Baracoa, the name of province on the coast, is from Ar. bara sea, koan to be there, “the sea is there;” in Barajagua the bara again appears; Guaymaya is Ar. waya clay, mara there is none; Marien is from Ar. maran to be small or poor; Guaniguanico, a province on the narrow western extremity of the island, with the sea on either side, is probably Ar. wuini wuini koa, water, water is there. The names of tribes such as Siboneyes, Guantaneyes, owe their termination to the island Arawack, eyeri men, in the modern dialect hiaeru, captives, slaves. The Siboneyes are said by Las Casas, to have been the original inhabitants of Cuba.28 The name is evidently from Ar. siba, rock, eyeri men, “men of the rocks.” The rocky shores of Cuba gave them this appellation. On the other hand the natives of the islets of the Bahamas were called lukku kairi, abbreviated to lukkairi, and lucayos, from lukku, man, kairi an island, “men of the islands;” and the archipelago itself was called by the first explorers “las islas de los Lucayos,” “isole delle Lucaí.”29 The province in the western angle of Haiti was styled Guacaiarima, which Peter Martyr translates “insulae podex;” dropping the article, caiarima is sufficiently like the Ar. kairuina, which signifies podex, Sp. culata, and is used geographically in the same manner as the latter word.

The word Maya frequently found in the names of places in Cuba and Haiti, as Mayaba, Mayanabo, Mayajigua, Cajimaya, Jaimayabon, is doubtless the Ar. negative ma, mân, mara. Some writers have thought it indicative of the extension of the Maya language of Yucatan over the Antilles. Prichard, Squier, Waitz, Brasseur de Bourbourg, Bastian and other ethnologists have felt no hesitation in assigning a large portion of Cuba and Haiti to the Mayas. It is true the first explorers heard in Cuba and Jamaica, vague rumors of the Yucatecan peninsula, and found wax and other products brought from there.30 This shows that there was some communication between the two races, but all authorities agree that there was but one language over the whole of Cuba. The expressions which would lead to a different opinion are found in Peter Martyr. He relates that in one place on the southern shore of Cuba, the interpreter whom Columbus had with him, a native of San Salvador, was at fault. But the account of the occurrence given by Las Casas, indicates that the native with whom the interpreter tried to converse simply refused to talk at all.31 Again, in Martyr’s account of Grijalva’s voyage to Yucatan in 1517, he relates that this captain took with him a native to serve as an interpreter; and to explain how this could be, he adds that this interpreter was one of the Cuban natives “quorum idioma, si non idem, consanguineum tamen,” to that of Yucatan. This is a mere fabrication, as the chaplain of Grijalva on this expedition states explicitly in the narrative of it which he wrote, that the interpreter was a native of Yucatan, who had been captured a year before.32

Not only is there a very great dissimilarity in sound, words, and structure, between the Arawack and Maya, but the nations were also far asunder in culture. The Mayas were the most civilized on the continent, while the Arawacks possessed little besides the most primitive arts, and precisely that tribe which lived on the extremity of Cuba nearest Yucatan, the Guanataneyes, were the most barbarous on the island.33

The natives of the greater Antilles and Bahamas differed little in culture. They cultivated maize, manioc, yams, potatoes, corn, and cotton. The latter they wove into what scanty apparel they required. Their arms were bows with reed arrows, pointed with fish teeth or stones, stone axes, spears, and a war club armed with sharp stones called a macana. They were a simple hearted, peaceful, contented race, “all of one language and all friends,” says Columbus; “not given to wandering, naked, and satisfied with little,” says Peter Martyr; “a people very poor in all things,” says Las Casas.

Yet they had some arts. Statues and masks in wood and stone were found, some of them in the opinion of Bishop Las Casas, “very skilfully carved.” They hammered the native gold into ornaments, and their rude sculptures on the face of the rocks are still visible in parts of Cuba and Haiti. Their boats were formed of single trunks of trees often of large size, and they managed them adroitly; their houses were of reeds covered with palm leaves, and usually accommodated a large number of families; and in their holy places, they set up rows of large stones like the ancient cromlechs, one of which is still preserved in Hayti, and is known as la cercada de los Indios.