полная версия

полная версияCardinal Newman as a Musician

For good operatic music Cardinal Newman had, we believe, more of a liking than for the more modern oratorio. Rossini, as a religious composer, was, we fear, in his bad books, yet when the choice had to be made at the 1879 Festival as to what performance he would attend, he at first said, "I shall go once, and I choose Mosé in Egitto." He was, he continued, fond of operatic music, and heard very little of it. "However," he added to two of the Fathers, "there's no reason why you shouldn't go to all." Perhaps there was one reason against that course; it would be expensive. There is an amusing notice of Rossini in the Anglican Letters of Mr. Newman. "Bowden tells me," he wrote in March, 1824, "that Sola, his sister's music-master, brought Rossini to dine in Grosvenor Place not long since; and that as far as they could judge (for he does not speak English) he is as unassuming and obliging a man as ever breathed. He seemed highly pleased with everything, and anxious to make himself agreeable. Labouring, indeed, under a severe cold, he did not sing, but accompanied two or three of his own songs in the most brilliant manner… As he came in a private, not a professional, way, Bowden called on him, and found him surrounded, in a low, dark room, by about eight or nine Italians, all talking as fast as possible, who, with the assistance of a great screaming macaw, and of Madame Rossini in a dirty gown and her hair in curl papers, made such a clamour that he was glad to escape as fast as he could."34

The revised Latin play, and music in conjunction, and all played by the boys themselves, were two striking traditions (not, we trust, to die out) of the Oratory School in our time, and they were institutions introduced by Dr. Newman there, and rooted in his affections from boyhood's associations. "Music was a family taste and pursuit," writes the late Miss Mozley, "Mr. Newman, the father, encouraged it in his children. In those early days they could get up performances among themselves, operatic or simply dramatic."35 At Ealing School he took the parts of Davus in the Andria, Cyrus in the Adelphi, and Pythias in the Eunuchus, as he told us himself; a varied répertoire, i. e. the confidential family servant, the young man about town, and the maid of all work! We see not only plays, and then music, and lastly the two together, but original composition also, early engaging his attention. He tells us, "In the year 1812 I think I wrote a mock drama of some kind… And at one time I wrote a dramatic piece in which Augustus comes on. Again, I wrote a burlesque opera in 1815, composing tunes for the songs."36

As to composing, he writes to his mother in March, 1821: "I am glad to be able to inform you that Signor Giovanni Enrico Neandrini has finished his first composition. The melody is light and airy, and is well supported by the harmony."37 We may add that Mr. Newman, Mr. Walker (afterwards Canon of Westminster), and Mr. Bowles, played together at Littlemore instrumental trios written by the Cardinal himself, and which Father Bowles once told us were "most pleasing." What has become of them?38 On our showing the Father in 1869 an original song to his words "The Haven,"39 he pointed to the second chord, exclaiming, "Ah, a diminished seventh!" We had no notion at that time what perpetrated iniquity that might be, but two years later he wrote: "Every beginner deals in diminished sevenths. At least, I did as a boy. I first learnt the chord from the overture to Zauberflöte; and henceforth it figured with powerful effect in my compositions. You must try to make a melody. Without it you cannot compose. Perhaps, however, it is that which makes a musical genius." If you have no ideas, in fact, go in con amore, for the chord of the diminished seventh.

On receiving a march, written by a pupil in 1873, he gently indicated faults while giving encouragement, and wrote in July, "It shows you are marching in your accomplishments. It is a very promising beginning… On reading it, I thought I had found some grammatical faults, but perhaps more is discovered in the province of discords, concords, and coincidences of notes than when I was a boy." And in September of the same year, "Thank you for your new edition of St. Magnus. On what occasion did he march? I know Bishops were warlike in the middle ages. However, whenever it was, his march is very popular here, and it went off with great éclat." Then he wrote to his correspondent in April, 1880, who talked about not being "skilled," "Why should you not qualify yourself to deserve the title of a 'skilled musician?' 'Skilled' is another word for 'grammatical' or 'scholarlike.'"

When an Oratory organist in the early days was shown a hymn with tune and accompaniment all composed by Dr. Newman himself (for insertion in the printed Birmingham Oratory Hymn Book), unaware of the authorship he at once corrected some of the chords. The Father Superior noticed this, and asked him why he had made the changes. The organist proceeded to advert to some consecutive fifths in the harmony. But, urged the Father, Beethoven and others make use of them. "Ah," came the answer, "it's all very well for those great men to do as they like, but that don't make it right for ordinary folk to do as they like." Dr. Newman therefore learned that musically he was only an ordinary folk, and he would have been the first to laugh down the notion that he was anything else; for a modest estimate of himself in many things was a very marked characteristic with him, and made him call his beautiful verse "ephemeral effusions" to Badeley, and write in May, 1835, apropos of a suggested uniform edition of his revised Latin plays, "I have not that confidence in my own performance to think I can compete with a classical Jesuit" (i. e. Father Jouvency). In 1828 he had contemplated writing an article on music for the London Review, along with one on poetry. The latter, in the event, alone saw the day; the former "seems to have remained an idea only."40 He is apologetic in the Idea of a University, when about to descant so eloquently upon music: "If I may speak," he says, "of matters which seem to lie beyond my own province;"41 but in very early Oratory days at Edgbaston, he essayed some lectures on music to some of the community in the practice-room. And at the opening of the new organ there in August, 1877, he "preached a most beautiful discourse [taken down at the time], upon the event of the day; and on music, first as a great natural gift, then as an instrument in the hands of the Church; its special prominence in the history of St. Philip and the Oratory; the part played by music in the history of God's dealings with man from first to last, from the thunders of Mount Sinai to the trumpets of the Judgment; the mysterious and intimate connection with the unseen world established by music, as it were the unknown language of another state. Its quasi-sacramental efficacy, e. g., in driving away the evil spirit in Saul and in bringing upon Eliseus the spirit of prophecy; the grand pre-eminence of the organ in that it gave the nearest representation of the voice of God, while the sound of strings might be taken as more fitted to express the varying emotions of man's state here on earth."42

At Oxford, in his time, he said, there were none of the facilities for music that now form part of the institutions of the place; there was little to encourage individual musical talent. At St. Clement's we only learn, "I had a dispute with my singers in May, which ended in their leaving the church, and we now sing en masse,"43 and in June still, "My singers are quite mute."44 At St. Mary's, Mr. Bennett, who was killed on his way to Worcester Festival by the upsetting of a coach,45 and after him Mr. Elvey, elder brother of Sir George Elvey, sometime organist at St. George's Chapel, Windsor, were Mr. Newman's organists. "I shall never forget," writes a hearer, "the charm it was to hear Elvey play the organ for the hymn at Newman's afternoon parochial service at St. Mary's on a Sunday. The method was to play the tune completely through on the organ before the voices took it up, and the way he did it was simply perfect."

Still the Anglican service, taken as a whole, was scarcely then calculated to stir artistic fervour, and this listener, so delighted with Elvey at St. Mary's, went home to his village parish church only to hear the hymn murdered, or if it were Advent, Christmas, or Easter, a tradesman shout from the gallery, "We will now sing to the praise and glory of God a hanthem!" when a motet would be sacrificed to incompetency with every circumstance of barbarity attending the execution. Mr. Newman in language of appalling force, written a year after his conversion, has described the Anglican service as "a ritual dashed upon the ground, trodden on, and broken piecemeal; prayers clipped, pieced, torn, shuffled about at pleasure, until the meaning of the composition perished, and offices which had been poetry were no longer even good prose; antiphons, hymns, benedictions, invocations, shovelled away; Scripture lessons turned into chapters; heaviness, feebleness, unwieldiness, where the Catholic rites had had the lightness and airiness of a spirit; vestments chucked off, lights quenched, jewels stolen, the pomp and circumstances of worship annihilated; a dreariness which could be felt, and which seemed the token of an incipient Socinianism, forcing itself upon the eye, the ear, the nostrils of the worshipper; a smell of dust and damp, not of incense; a sound of ministers preaching Catholic prayers, and parish clerks droning out Catholic canticles; the royal arms for the crucifix; huge ugly boxes of wood, sacred to preachers, frowning on the congregation in the place of the mysterious altar; and long cathedral aisles unused, railed off, like the tombs (as they were) of what had been and was not; and for orthodoxy, a frigid, unelastic, inconsistent, dull, helpless dogmatic, which could give no just account of itself, yet was intolerant of all teaching which contained a doctrine more or a doctrine less, and resented every attempt to give it a meaning."46 The Catholic Church's ritual he found very different.

"What are her ordinances and practices," he asks, "but the regulated expression of keen, or deep, or turbid feeling, and thus a 'cleansing' as Aristotle would word it, of the sick soul? She is the poet of her children; full of music to soothe the sad, and control the wayward – wonderful in story for the imagination of the romantic; rich in symbol and imagery, so that gentle and delicate feelings, which will not bear words, may in silence intimate their presence, or commune with themselves. Her very being is poetry; every psalm, every petition, every collect, every versicle, the cross, the mitre, the thurible, is a fulfillment of some dream of childhood, or aspiration of youth. Such poets as are born under her shadow, she takes into her service, she sets them to write hymns, or to compose chants, or to embellish shrines, or to determine ceremonies, or to marshal processions; nay, she can even make schoolmen of them, as she made St. Thomas, till logic becomes poetical."47

And, of course, as the Catholic poet that he now was, he duly set about to "write hymns" and "to compose chants." Since 1834, it will be found, his original muse, amid the "encircling gloom," had been entirely silent, but once emerging into the light of the true faith, it struck the lyre again with those most lovely notes of "Candlemas" —

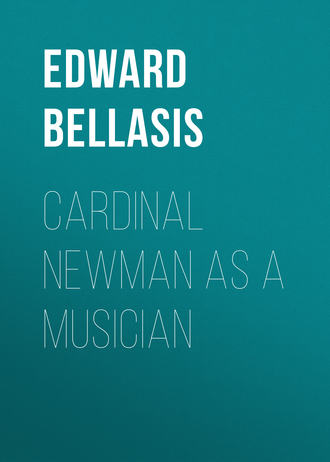

The Angel-lights of Christmas-morn,Which shot across the sky,Away they pass at Candlemas,They sparkle and they die.48In 1849 appeared his most original and pathetic "Pilgrim Queen," or No. 38, Regina Apostolorum, in the Hymn Book, the sweet music thereto being his own composition, (or in part adaptation?)

[Listen]

There sat a Lady all on the ground,Rays of the morning circled her round;Save thee, and hail to thee, gracious and fair,In the chill twilight what wouldst thou there?

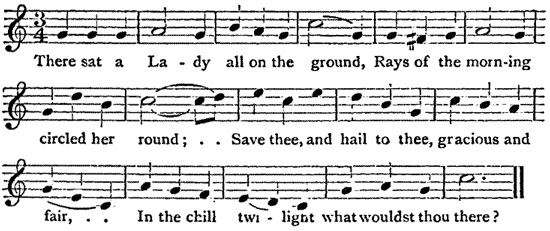

In 1850 came two more exquisite hymns in honour of the Mother of God, i. e., the "Month of Mary," and the "Queen of Seasons," both headed Rosa Mystica in the hymn-book. The hymns and tunes of two others, of No. 51. "Regulars and St. Philip," (an expressive melody),

[Listen]

The holy monks conceal'd from menIn midnight choir or studious cell,In sultry field or wintry glen,The holy monks, I love them well,In sultry field or wintry glen,The holy monks, I love them well.

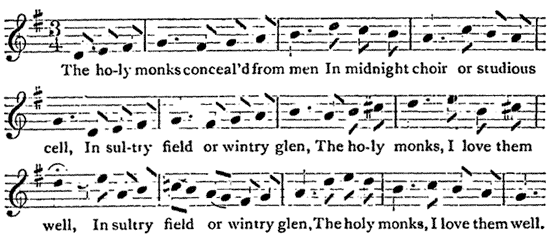

and No. 81, "Night" ("The red sun is gone," from the Breviary),

[Listen]

The red sun is gone,Thou light of the heart,Blessed Three Holy One,To Thy servants a sunEverlasting impart.

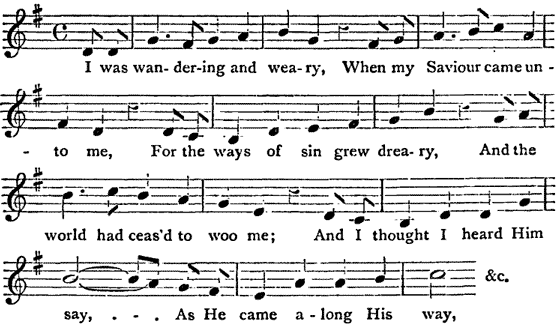

are also by him; and there may be others. And though this tune to No. 81 has been irreverently referred to as being "just like an old sailor's song," the same critic has extolled its effect, and told us how he loved to sing its long note at eventide. No. 61, "Conversion," is Father Faber's hymn, "I was wandering and weary" (No. 66 in the London Oratory Hymn Book49), but the original air in both Oratory books is the same, and the composition of Cardinal Newman.

[Listen]

I was wandering and weary,When my Saviour came unto me,For the ways of sin grew dreary,And the world had ceas'd to woo me;And I thought I heard Him say,As He came along His way, &c.

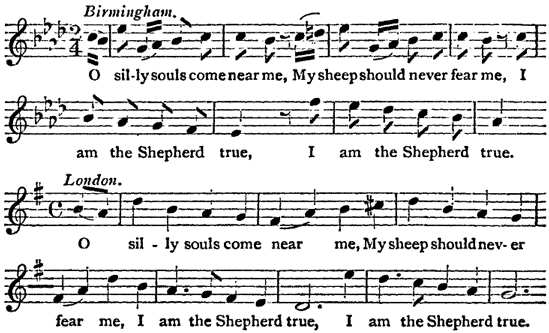

Its peculiar merits grow upon familiar acquaintance, and a devoted lover of plain chant, rather to our surprise, once expressed his affection for it. It has been termed "briny," like No. 81. Its expressiveness and "go" are unquestionable,50 and it is becoming popular without the public in general knowing who the composer is. The study of the application of music to words was interesting enough, as the Cardinal remarked in April, 1886. Sometimes the music could not quite fit in with the words,51 and one or other had to give way, and on our referring to this music to Father Faber's hymn "Conversion," he said he had an idea that the words had been somewhat altered to suit his tune. The reverse would appear to be the case. At least the refrain, "O silly souls," &c., is not identical in the Birmingham and London books.

[Listen]

BirminghamO silly souls come near me,My sheep should never fear me,I am the Shepherd true,I am the Shepherd true.LondonO silly souls come near me,My sheep should never fear me,I am the Shepherd true,I am the Shepherd true.

Mr. W. Pitts, the compiler of the latter, sends us word that "the melody only came into my hands, and it stands in the London book exactly as I received it. I think it was sent by one of the Birmingham Fathers, or by Mr. Edward Plater." This is satisfactory, and points to a smoother and far more effective version of the refrain by the composer himself.52

Altogether we have ever felt that there is an indescribable brightness, a radiant cheerfulness, which might have pleased St. Philip, about the Birmingham selection of hymns and tunes, with Beethoven, Mozart, Mendelssohn, Pleyell, Crookall, Webbe, Moorat, and others laid under contribution. In the Saint's time, we know, "there were sung at the Oratory many Laudi, motets, madrigals, and sacred songs in the vulgar tongue, and these gave scope for composers to essay a simpler, and more popular and stirring style of music."53 Take up then the Father's book, hear the people at the May devotions sing such winning songs as the "Pilgrim Queen" (No. 38, Regina Apostolorum), and the "Month of Mary" (No. 32, Rosa Mystica), or listen during St. Philip's Novena, to "St. Philip in his School" (No. 49), "in his Mission" (No. 50), "in Himself" (No. 51, "Regulars and St. Philip"), and "in his Disciples" (No. 54, "Philip and the Poor"), and we conclude that, as with the Saint, so with his distinguished son, it has been his "aim to make sacred music popular;"54 and may we not further say that the Cardinal, without any parade whatever, but in the simplest fashion, has somehow succeeded at Birmingham in his aim?

The Birmingham Oratory Book, with the tunes, only privately printed for local use, came, nevertheless, as a surprise to Messrs. Burns and Westlake, who made merry over the occasional simplicity, not to say meagreness of the harmonies. A quick movement, too, from a Beethoven Rasoumousky quartet, is rather awkward, albeit taken slow, for No. 74, "Death," and Leporello's song for Nos. 22 and 23, is possibly not over suitable, however intrinsically appropriate, looking to the associations it might arouse, not so much, however, among the poor, who cannot afford to patronize opera, as among the rich. "Just look at the harmony," says one of No. 51; and of the famous No. 61, "there is a strange want of unity, the first part has no second harmony." A noble lord, too, disapproved of No. 51, the notes being, said he, all over the key-board, but such are the strains of some of the best music in the world, and the notice to this anonymous collection is almost an answer to particular criticism, as Burns felt at once, i. e.: "Neither the following tunes themselves, nor the hymns to which they belong, have been brought together on any one principle of selection, or to fulfil any ideal of what such composition ought to be. Many of them have grown into use insensibly, without any one being directly responsible for them; the rest have been adapted as the most appropriate, under circumstances, to complete the set, and to answer the needs of our people."55

Like St. Philip, too, "he took the word music in its widest sense, and made use of both vocal and instrumental music, and of their blended harmony."56 While we believe that he would have been the first to admit the beauty of large portions of the old chant, its incomparable hymns in the liturgy, the familiar accentus dear to every Catholic ear, for the Preface, the Pater noster, &c., the modes for Holy week, the tones for the Psalms of the Divine Office, &c., we question whether he could have made much of a mass of antiphons that seem to illustrate the sacred text, "All we like sheep have gone astray." "In Gregorian music," said a writer in 1890, speaking more positively than we are able to do, "Newman could see no beauty whatever – none, at any rate, in the usual antiphons and 'tones.' An exception must be made in favour of those familiar chants occurring in the Mass… I recollect his telling me, after we had heard one of Cherubini's Masses admirably performed at a Birmingham Festival, that the music, though so beautiful, needed the interspersing of those quaint old chants to make it really devotional," but "I believe," writes a friend, "it is very difficult for one who has heard only Mozart and Beethoven, &c., in all his early years ever to get a liking for Gregorian tones. It used to drive Canon Oakeley wild when he heard his nephew, the present Sir H. Oakeley, play a fugue of Bach's even on the organ. The Cardinal, however, liked the modus peregrinus to the In exitu Israel (that was only natural), and I remember once he seemed quite put out because once we followed the Rubrics in Easter week (when the In exitu is used) by having all the Psalms to one tone. For a moment it seemed as if he would contradict himself in his strict rule of going by authority against what he liked, and would change the tones so as to have the peregrinus." He somewhere, however, calls Gregorian an "inchoate science." Could mediæval work, largely out of touch with the times, claim for itself a monopoly of existence to the exclusion of the modern? So loyal a son of Holy Church as Dr. Ward had let fall that a plain chant Gloria reminded him of "original sin." "And, if sometimes," writes a friend of old Oratory days, "we were so unfortunate as to have on some week-day festival of our Lady, only the Gregorian Mass, Father Darnell used to say we were 'burying our Lady,' and though he would make no remark, I have little doubt the Father thought so too." Perhaps, then, Cardinal Newman's love for vocal and instrumental ecclesiastical music in combination (especially at Christmas, Easter, and Pentecost) was a true instinct recognizing the undoubted needs of another day, and is best labelled for a motto with some verses of the 149th and 150th Psalms, which we recommend to the attention of a few purists in case they may have forgotten them? Thus, acknowledging in January, 1859, the Gothic to be "the most beautiful of architectural styles," he "cannot approve of the intolerance of some of its admirers," and he would "claim the liberty of preferring, for the purposes of worship and devotion, a description of building which, though not so beautiful in outline, is more in accordance with the ritual of the present day, which is more cheerful in its exterior, and which admits more naturally of rich materials, of large pictures or mosaics, and of mural decorations."57

"My quarrel with Gothic and Gregorian when coupled together," says Campbell, in Loss and Gain, "is that they are two ideas not one. Have figured music in Gothic churches, keep your Gregorian for Basilicas." Bateman: "… You seem oblivious that Gregorian chants and hymns have always accompanied Gothic aisles, Gothic copes, Gothic mitres, and Gothic chalices." Campbell: "Our ancestors did what they could, they were great in architecture, small in music. They could not use what was not yet invented. They sang Gregorian because they had not Palestrina." Bateman: "A paradox, a paradox." Campbell: "Surely there is a close connection between the rise and nature of the Basilica and of Gregorian unison. Both existed before Christianity, both are of Pagan origin; both were afterwards consecrated to the service of the Church." Bateman: "Pardon me, Gregorians were Jewish, not Pagan." Campbell: "Be it so, for argument sake, still, at least, they were not of Christian origin.58 Next, both the old music and the old architecture were inartificial and limited, as methods of exhibiting their respective arts. You can't have a large Grecian temple, you can't have a long Gregorian Gloria." Bateman: "Not a long one, why there's poor Willis used to complain how tedious the old Gregorian compositions were abroad." Campbell: "… Of course you may produce them to any length, but merely by addition, not by carrying on the melody. You can put two together, and then have one twice as long as either. But I speak of a musical piece, which must, of course, be the natural development of certain ideas, with one part depending on another. In like manner, you might make an Ionic temple twice as long or twice as wide as the Parthenon; but you would lose the beauty of proportion by doing so. This, then, is what I meant to say of the primitive architecture and the primitive music, that they soon come to their limit; they soon are exhausted, and can do nothing more. If you attempt more, it's like taxing a musical instrument beyond its powers."… Campbell: "This is literally true as regards Gregorian music, instruments did not exist in primitive times which could execute any other."… Reding: "… Modern music did not come into existence till after the powers of the violin became known. Corelli himself, who wrote not two hundred years ago, hardly ventures on the shift. The piano, again, I have heard, has almost given birth to Beethoven." Campbell: "Modern music, then, could not be in ancient times for want of modern instruments, and, in like manner, Gothic architecture could not exist until vaulting was brought to perfection. Great mechanical inventions have taken place both in architecture and in music, since the age of Basilicas and Gregorians; and each science has gained by it." Reding: "… When people who are not musicians have accused Handel and Beethoven of not being simple I have always said, 'is Gothic architecture simple?' A Cathedral expresses one idea, but is indefinitely varied and elaborated in its parts; so is a symphony or quartet of Beethoven." Campbell: "Certainly, Bateman, you must tolerate Pagan architecture, or you must in consistency exclude Pagan or Jewish Gregorians, you must tolerate figured music, or reprobate tracery windows." Bateman: "And which are you for, Gothic with Handel, or Roman with Gregorian?" Campbell: "For both in their place. I exceedingly prefer Gothic architecture to classical. I think it is the one true child and development of Christianity; but I won't for that reason discard the Pagan style which has been sanctified by eighteen centuries, by the exclusive love of many Christian countries, and by the sanction of a host of saints. I am for toleration. Give Gothic an ascendancy; be respectful towards classical."… Reding: "Much as I like modern music, I can't quite go the length to which your doctrine would lead me. I cannot, indeed, help liking Mozart; but surely his music is not religious?" Campbell: "I have not been speaking in defence of particular composers, figured music may be right, yet Mozart or Beethoven inadmissible. In like manner you don't suppose, because I tolerate Roman architecture, that therefore I like naked cupids to stand for cherubs, and sprawling women for the cardinal virtues… Besides, as you were saying yourself just now, we must consult the genius of our country, and the religious associations of our people." Bateman: "Well, I think the perfection of sacred music is Gregorian set to harmonies; there you have the glorious old chants, and just a little modern richness." Campbell: "And I think it just the worst of all, it is a mixture of two things, each good in itself, and incongruous together. It's a mixture of the first and second courses at table. It's like the architecture of the façade at Milan, half-Gothic, half-Grecian." Reding: "It's what is always used, I believe." Campbell: "Oh, yes, we must not go against the age, it would be absurd to do so. I only spoke of what was right and wrong on abstract principles; and to tell the truth, I can't help liking the mixture myself, though I can't defend it."59