полная версия

полная версияIreland as It Is, and as It Would Be Under Home Rule

"I used to regard Mr. Gladstone as an honest man. Now I think otherwise. As for the ruck that follow him – well, if they were intelligent when honest, or honest when intelligent, nobody could understand their deviation from the path of reason and rectitude. But the rogues will of course do anything they think will suit them best, no matter what befalls their country; and as for the rest, why of course no reasonable man would blame people for not thinking, when Providence has not provided them with the requisite machinery."

Ballyshannon, August 5th.

No. 58. – THE TRUTH ABOUT BUNDORAN

There is no railway between Donegal and Ballyshannon, fifteen miles away. The largest town in the county is not connected with the principal port. But you can steam from Ballyshannon to Bundoran, the favourite watering-place of Donegal, quaint and romantic, with a deep bay and grassy cliffs. The bathing-grounds have a smooth floor of limestone, and the Atlantic rolls in majestically, sending aloft columns of white spray as its waters strike the outlying islands of rock, each with a green crown of vegetation. The bare-headed and bare-legged natives walk side by side with the fashionably-dressed citizens of Dublin, Belfast, and Londonderry. The poorest folks are tolerably clean, and, unlike the Southerners, occasionally wash their feet. The town is small, but there is plenty of good accommodation for holiday makers. Bundoran is Catholic and intolerant. Although depending on their Protestant countrymen for nine-tenths of their livelihood, the people of Bundoran object to Protestantism, and the intensity of their antipathy to the Black-mouths has impelled them to quarrel with their bread-and-butter. Of late the question of tolerance has been much discussed. Sapient persons whose assumption is equal to their ignorance of the subject, affect to despise the fears of the scattered Protestant population whose alarm is based on the experience of a lifetime. English Home Rulers who wish to create effect unblushingly affirm that the Protestants are the only intolerants, and that the Papists are as distinguished for affectionate toleration as for industry and honesty. In direct opposition to daily experience and the evidence of history, they assert that the Papists are the persecuted party, and that they only practise their religion with fear and trembling. Notwithstanding the well-known doctrine of the Roman Church, which preserves heaven exclusively for those within its own pale, these eccentric politicians aver that under a Roman Catholic Parliament, elected by the clergy alone, the isolated Protestants of Catholic Ireland, known in the Papist vernacular as Black-faces, Black-mouths, Heretics, Soupers, and Jumpers, would be treated with perfect consideration, would enjoy the fullest freedom, the most indulgent toleration, would, in short, be placed in a position of equality with the predestined inhabitants of Paradise, or, to quote Catechism, the inheritors of the Kingdom of Heaven. The persons most nearly concerned know better. The shrewd farmers of Ulster, like the Puritan brethren of Leinster, Munster, and Connaught, are entirely devoid of faith in the promised Papist toleration. Protestant equality under a Home Rule Parliament! You might as well tell them to plant potatoes and expect therefrom a crop of oats. Men do not gather grapes off thorns nor figs off thistles.

The Bundoran Protestants have evidence to offer. The date is recent. Not two hundred years ago, but in the year of grace eighteen-hundred-and-ninety-three. Seeing that the little seaside resort was full of holiday-makers from the Protestant counties of Fermanagh and Tyrone, two young Protestant clergymen determined to hold Gospel services in a tent which was pitched in a field the property of Mr. James A. Hamilton, J.P. For about a week beforehand handbills announcing the services for July 21 had been distributed in the town and suburbs, but no controversial topic was mentioned, nor was it intended that the services should be other than strictly evangelical. The tent was erected solely to accommodate the great influx of visitors, after the manner so familiar in England. Here was a test of Papal toleration. The tent was on private ground, and if Papists did not like it they could easily keep away, making a wry face and spitting out the abomination as they passed, after their liberal custom. This, however, was not enough. No sooner had the handbills been issued, than a most scurrilous placard appeared, calculated to inflame the passions of the ignorant, and to make them act after their kind. The Gospellers were accused of an attempt to poach on the Papal preserves, and it was mockingly stated that they had at last come to Christianise the benighted Papists. The effect of this placard was soon evident. It became known that the Roman Catholics of the district had determined that they would allow no Gospel services in Bundoran. The police authorities, who know all about Papist "tolerance," increased the small village force to twenty-five men, but, as the result proved, these were absolutely useless. A mob of more than a thousand pious ruffians gathered early in the evening, and attacked in a brutal and merciless manner every person they suspected of being on the way to the meeting. The two Evangelists went to the tent under the escort of the twenty-five policemen, but before they could commence the service the apostles of toleration made a desperate rush on the congregation, most of whom were struck with bludgeons and stones, knocked down, kicked, and otherwise maltreated. The constabulary with great determination, but with much difficulty, protected the two young clergymen, upon whom a most venomous attack was made. The Protestants defended themselves with umbrellas, walking-sticks, and the like, but being strongly charged these proved of little avail against the wild onslaught of the party of toleration. Well may the local paper say that "a regular panic pervades the resident and visiting Protestant families."

Mr. Morley, replying to a question in the House, said the reports were exaggerated. The hapless Irish Secretary, unable to meet this and similar charges with denial, always relies on the plea of "exaggeration." The statement given above is derived from eye-witnesses of both creeds, and from an official source. One word as to the plea of exaggeration.

When I had investigated the fifteen moonlighting atrocities of four weeks in County Limerick, the County Inspector, who had just returned from a conference with Mr. Morley, said to me: —

"Everything is ve-ry quiet. We're going on very nicely now." But the Gazette gave particulars of the shooting in the legs of the four members of the Quirke family, and Mr. Morley was obliged to admit the fifteen outrages which constituted County Inspector Moriarty's idea of "quiet." Subordinates will say there is peace when there is no peace, if the master requires it. The Bundoran outrage is not susceptible of exaggeration. Call another witness.

The Sligo Independent, which being published on the spot can speak with authority, says that "the intolerant and bigoted Roman Catholics of Bundoran and surrounding districts look upon Protestantism as a kind of leprosy which ought at all hazards to be stamped out," and further states that "even the ladies did not escape their fanatical hatred and fury. Several people were severely injured, and a clergyman who was coming to the meeting with his Bible in his hand, was thrown down and badly beaten, the Book being torn from him and destroyed. What may Protestants expect should the Home Rule Bill ever become law, when such disgraceful outbursts of religious bigotry are quite common under the existing régime? The natural conclusion is that all such Gospel meetings would be put down with a strong hand, and Protestant religious liberty trampled under foot by their unscrupulous Roman Catholic fellow-countrymen. And yet Loyalists are told to trust in them and all will be well!" Thus the Sligo journal; and its editor may perhaps, under the circumstances, be pardoned for suggesting that "it were better for Loyalists not to put themselves in the power of men who have proved themselves unfit even to associate with civilised beings. Bundoran will feel the evil effects of these insane attacks upon defenceless people next season when tourists and pleasure-seekers will avoid this seat of stupid bigotry, and visit some other summer resort where they will at least be allowed to worship their Maker according to their own desires." Exactly. Many visitors left at once, and will never return. During my six hours' stay I heard complaints of the falling-off of business. If the place be empty next summer the people will attribute the loss to the British Government, and especially to the machinations of the Tory party. An old fisherman said the fish had left the bay. I assured him they would return under a Dublin Parliament. He refused to be comforted, because they were not.

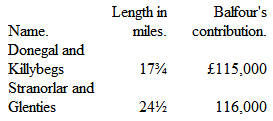

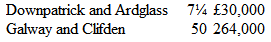

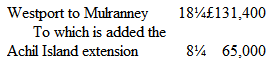

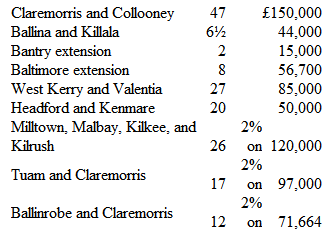

There is no railway from Bundoran to Sligo, that is, no direct railway. The great lines mostly run from east to west, but the west lacks connecting links. Look at the map of Ireland. Cast your eye on the west coast. If you would go by rail from Westport to Sligo, you must first go east to Mullingar. If you would go by rail from Sligo to Bundoran, you must first go east to Enniskillen. If from Bundoran to Donegal, less than twenty miles, you must again go to Enniskillen, thence to Strabane, where you arrive after the best part of a day's journey, ten miles further away than when you started, thence to Stranorlar, changing there to the narrow-gauge railway for your final trip. Travelling on the west coast is tedious and expensive, whether you go round by rail or drive direct. Many of the most attractive tourist districts are almost inaccessible. To open them up is to enrich the neighbourhood. Few Englishmen know what the Balfour railways really mean. The following statement gives particulars respecting the Light Railways authorised by the Salisbury Government, and constructed either wholly or in part by the nation. These railways introduce tourists to those parts of Ireland which are best worth visiting, and the economy of time, money, and muscular tissue effected by them would be hard to overestimate. But this is not all, nor was this their primary purpose. They gave and still give employment to the people of the district, and besides bringing the money of the tourists into the country, enable the natives to send their produce out of it, to place it on the market, to turn it into gold. There is no railway from Dugort, in Achil, to any market. Fish caught in Blacksod Bay are therefore worth nothing except as food for the fisherman's family. Large crabs were offered to me for one halfpenny each. Does this fact impress the usefulness of Balfour's railways? Here they are complete: —

On this line you run for twelve miles from Stranorlar without seeing a single cottage. There are none within sight on either side.

This will run in connection with the splendid system of the Midland and Western Railway, opening up the grand scenery of Connemara, which to the average Britisher is like a new world. No end of fishing here among virgin shoals of trout and salmon, and nearly always for nothing. It was along the first sixteen miles of this line, still unopened, that I ran on the engine to Oughterard.

This will enable travellers to steam from Dublin to Achil Island viâ Midland and Western, instead of the ten hours on an open car, which on their arrival at Westport now awaits visitors to Dugort. It was on this line that I had the startling adventures on a fiery untamed bogey engine, lent to the Gazette by Mr. Robert Worthington, of Dublin. But I must condense.

Besides these, similar lines have been constructed, and are now working between Tralee, Dingle, and Castlegregory; Skibbereen and Skull; Ballinscarty, Timoleague, and Courtmacsherry. The Cork and Muskerry Railway, which runs through the groves of Blarney, owes its completion and success to Mr. Balfour's administration.

Driving from Bray to the Dargle, my jarvey pointed to the ruins of a light railway undertaken without the aid of the British intellect. "'Tis a nice mess they made iv it, the quarrelin' pack o' consated eejits! They must run a chape little thing to the Dargle, about two miles away, along the roadside, just as Balfour showed them the way. What have they done? Desthroyed the road. Lost all the money they could raise. Got the maker to take back the rails (for they bought thim afore they wanted thim), an' the only thing they now have in the shape of shareholders' property is a lawsuit wid the Wicklow folks about desthroyin' the road. Faix, an iligant dividend is that same. An' them's the chaps that's to rule the counthry. That's the sort of thim, I mane. Many's the time I seen the Irish mimbers. Sorra a thing can they do, barrin' dhrink an' talk. I wouldn't thrust one of thim to rub down a horse, nor wid a bottle of poteen. Divil a one of thim but would dhrink as much whiskey as would wash down a car, an' if they could run as fast as they can talk, begorra, ye might hunt hares wid thim. Rule the counthry, would ye. Whe-w-w-w!" He whistled with a "dying fall," like the strain in Twelfth Night.

I drove from Bundoran to Sligo, the sea on the right, the Benbulben mountains on the left, singularly shaped but splendid. The round towers and ancient Irish crosses, the lakes and rivers of Sligo, are full of interest and beauty. The Abbey ruins are exceptionally fine. The town is fairly well built, but it is easy to realise that once more it is Connaught. During a turn round Bridge Street, a country cart heaves alongside, steered by a stalwart man in hodden gray. He notes the stranger, and politely says,

"Can I be of any use? I see you are a visitor."

We fell into conversation. Presently I said, "Everything will be well when you get Home Rule."

He stopped the cart and protested against this statement. Unknowingly I had tapped a celebrity. My hodden-gray friend was none other than the famous Detective James Magee, who arrested James Stephens, the Number One, the Head Centre of the Irish Revolutionary Brotherhood; also John O'Leary, editor of the Fenian Irish People, of which O'Donovan Rossa was business manager. O'Leary was a doctor hailing from Tipperary. He asked Magee if he might have his "night-cap," and his captor allowed him to call for the whiskey at a well-known Dublin resort, on parole of honour. Later, as a crowded street was reached, O'Leary said, "There are three thousand of my friends there. If you go that way I cannot save you. Better try a back street." "That was handsome," said Mr. Magee. "O'Leary was a gentleman. Stephens was only a 'blower.'" My friend was unalterably set against Home Rule, which he regards as an empty, foolish cry. Being a pensioner he wishes to be reticent, but his opinion is pronounced, and the Sligo people know it. He has a high opinion of the law-abiding instincts of his compatriots, and believes that "if they were left to themselves" the district would need no police. "A better-hearted, kinder, more obliging people never lived," said this excellent judge, who after twenty-seven years of police service, returned to end his days among them. And my short experience of the Sligo folks confirms this statement. They were not all so reserved as Detective-sergeant Magee. A thriving shopkeeper said: – "The majority, if you count noses, are for Home Rule, but if you count only brains and intelligence you would find an overwhelming majority against it. Mr. Gladstone and his set of blockheads seem quite impervious to reason, and even the constituencies of England seem to lack information. The reason is plain. While we have been minding our work the Nationalists have been agitating. For thirteen years they have been on the stump, and have stolen a march on us and they take a lot of catching up. We allowed them to empty their wind-bags, forgetting that the English people were not so conversant with the facts or with the character of the orators as we are. We thought that no precautions were required, and that their preposterous statements would be received in England as intelligent, enlightened people would receive them here. Their strength in Ireland is almost entirely among the illiterates, who in the polling booths are coerced by their priests. I have seen a man crying because he had not been allowed to vote for the candidate supported by his employer. Such a ridiculous thing could not happen in England, and Englishmen who do not know Ireland and the Irish will scarcely credit it. This shows how unable most Saxons are to understand Irish character and motive.

"All our civilisation is from England, all our progress, all our enlightenment, and nearly all our money. As a poor, helpless, semi-barbaric country, we ought to cleave to England with all our might and main. A more and more complete and perfect unity is our best hope. To ask for separation is the wildest absurdity. And just as we were beginning to go along smoothly! That was entirely due to the just but firm administration of the Balfour period.

"Among Irishmen justice with firmness is always appreciated in the long run. An Irish Secretary needs the hand of iron in the velvet glove. Paddy spots the philanthropic fumbler in a moment, and uses him, laughing the while at what he rightly calls his 'philandering.' Morley means well, but nobody here respects him. He knows no more of Irish character than a blind bull-pup. His master in my opinion is worse, if possible. He is deaf to all the arguments of Irish sense and Irish culture, and proposes to finally resolve the unresolvable, to settle the Irish difficulty by a Catholic Parliament. As well go out with a net to catch the wind. He listens to the representatives of ruffianism, counting them first. We kept silent too long. We thought the donkeys might bray for ever without shaking down the stars. We were wrong. Now we are almost powerless. For what are a handful of reasonable men against a crowd of blackguards with big sticks?"

While conversing with Detective Magee, that astute gentleman pointed out The O'Connor, lineal King of Connaught, and a staunch Unionist! A devout Catholic and intensely Irish, yet the uncrowned King is a loyalist. But The O'Connor is a man of superior understanding. After this I saw three Home Rulers – yea, I conversed with four, one a positive person whom I mistook for a farm labourer, but who proved to be a National schoolmaster who absorbed whiskey like the desert sands. A decent farmer who thought the Land League the finest thing in the wuruld, complained that while the British Government have contracted for hay at £8 15s., yet he and his friends could only get £3 for "best saved." His idea of Home Rule was – No Rent to pay. A ferocious commercial traveller, whose jaw and cheekbones were as much too large as his eyes and forehead were too small, wanted to know "what right had England to rule Ireland? Ye have no more right to rule Ireland than to rule France." This was his only idea. He was a patriot of the sentimental type, and wished that Ireland might take her place as an independent nation with Belgium, Switzerland, Holland. His hero was Paddy O'Donnell, of Bedlam —clarum et venerabile nomen– who for five days held his house, since called the Fort, against a strong force of police. "If all was like O'Donnell, we'd soon have the counthry to ourselves," said my commercial friend. "An' if ye don't let us go, we'll make ye wish ye did. Wait till ye get into throuble with France. The Siam business may yet turn up thrumps." He was very voluble, very loud, very illiterate, and I declined to discuss the question except in Irish, which he did not speak. Like most of the patriot orators of Ireland, he was as ignorant of his native language as of his native literature, and every other. This is the class from whom the political speakers who infest country places are drawn. At first sight they seem unworthy of notice, but contempt may be pushed too far. Even wasps become dangerous when in swarms. And Hatred is like fire: it makes even light rubbish deadly.

Sligo, August 8th.

No. 59. – IRISH NATIONALISM IS NOT PATRIOTISM

My tour through Ireland having now come to an end, I propose to sum up the conclusions I have formed in this and the three following articles. In connection with the Home Rule Bill, we have heard much of the "aspirations of a people." Mr. Gladstone has taken up the cry, and his subservient followers at once brought their speeches and facial expressions into harmony with the selected sentiment. These anti-English Englishmen would fain pose as persons in advance of their time, determined to do justice though the heavens should fall. They agree with Mr. Labouchere that John Bull is a tyrant, a robber, and a hypocrite, and that it is high time justice should be done to Ireland. As no substantial injustice exists, it is necessary to fall back on sentiment, and to quote the "aspirations of a people." The desire for a system of Irish autonomy is praised as a manifestation of patriotism which in all ages of the world has been honoured by worthy men. The English supporters of Mr. Gladstone, with their assumption of superior virtue, their Pharasaic We are not as other men, nor even as these Tories, would have us believe that with the granting of self-rule Ireland will be satisfied, that the gratification of a laudable sentiment is all that is now required to bind together the peoples in an infrangible Union of Hearts, and that peace and prosperity will at once follow in the wake of this merely sentimental concession.

The great mass of the Irish electorate know nothing of all this. Tap them wherever you will, north, south, east, or west, and you find one dominant thought – that of pecuniary gain. They know nothing of the proposed bill, and are totally incapable of comprehending its scope and effect. The peasantry of Ireland are actuated by motives entirely different from those affecting the rural constituencies of England. The Briton is proud of his country, believes in its might, justice, supremacy; and despite occasional grumbling is satisfied that the powers that be will do him right in the long run. The Irish peasant is essentially inimical to England. He is always "agin the Government" – that is, the rule of England. He regards the landlord as trebly an enemy – firstly as a heretic, secondly as the representative of British rule, and last, but by no means least, as the person to whom rent is due. He desires to abolish the landlord, not in the interests of religion – I speak now of the peasantry, and not the clergy – and not in the interests of patriotism, for if a Dublin Parliament were to cost him sixpence, the priests themselves could hardly drag him to the poll; but purely and simply to avoid any further payment of what he regards as the accursed impost on the land. Phillip Fahy, the leading light of Carnaun, near Athenry, is exactly typical of rural Irish Patriotism. "Did ye hear of the Home Rule Bill? What does it mane, at all, at all? Not one o' us knows more than that lump o' stone ye sit on. Will it give us the land for nothin', for that's all we hear? We'll be obliged av ye could explain it a thrifle, for sorra one but's bad off, an' Father O'Baithershin says 'Howld yer whist,' says he 'till ye see what'll happen,' says he. Will we get the bit o' ground widout rint, yer honner's glory?" Mr. Tynan, of Monivea, said that his landlord was liberal and good, and admitted that his land was not too highly rented, but, said he, "We have no objection to do better still." The run on the Irish Post Office Savings Banks at once illustrates the patriotism of the people and their confidence in the proposed Dublin Parliament. It was well known and understood, so far as the poorer classes are capable of understanding anything, that the floating balance of the Post Office Banks would constitute the only working capital of the Irish Legislature. Here was an opportunity for self-sacrifice. Here was a chance of manifesting the faith animating the lovers of their country. But at the same time it was made known that the Post Office would pass from the British control to that of the Irish people's chosen representatives. It might have been supposed that the electors would rejoice thereat with exceeding great joy, and that in order to show their trust in an Irish Parliament they would increase their deposits, and at considerable personal inconvenience refrain from withdrawals. Nothing of the kind. The "aspirations of a people" were at once strongly defined, but this time not in the direction of patriotism. It availed not to urge upon them the argument that the four millions of the Post Office Savings Banks were absolutely necessary to the successful administration of an Irish Parliament. In patriotic Dublin the run on the Post Office was tremendous. The master of a small sub-office told me that the withdrawals over his counter had for some time amounted to £200 per week, and that they were increasing to £70 per day. There was not enough gold in Dublin to meet the demands, and cash was being forwarded from London. The patriots who had no money deposited in the Post Office made no secret of their indignation, stigmatising their fellow-countrymen as recreants and traitors, but without perceptible effect. The Dublin Savings Bank became the trusted depositary of the money. This institution is managed by an association of Dublin merchants, not for profit, but for the encouragement of thrift, and the confidence reposed in them was doubtless due to the fact that the directors, on the introduction of the Home Rule Bill, had publicly announced their intention, on the bill becoming law, to pay twenty shillings in the pound and at once to close the bank. The patriot depositors were not deterred by this announcement, nor by the directors' letter to Mr. Gladstone, in which they declared that their determination to wind up the affairs of the bank was due to the fact that in the interest of their depositors they felt themselves unable to accept the security of an Irish Legislature. Patriotism would surely have resented this imputation. But Nationalism in its present phase is nothing more than selfish cupidity and lust of gain. This is made abundantly manifest by the freely-uttered sentiments of all classes of the Nationalist party. The first answer I received to an inquiry as to what advantages would be derived from a patriot Parliament was elicited from an ancient Dubliner, whose extraordinary credulity was equal to anything afterwards met with in the rural districts: – "The millions an' millions that John Bull dhrags out iv us, to kape up his grandeur, an' to pay sojers to grind us down, we'll put into our own pockets, av you plaze." The complaint about the British Government veto on Irish mining, which I fondly believed to be sporadic, proved to be chronic, universal. Here again the notion of easily acquired wealth was the impulse, and not the pure and self-denying influence of patriotism. "The British Government won't allow us to work the gold mines in the Wicklow mountains. Whin we get the bill every man can take a shpade, an', begorra! can dig what he wants. The Phaynix Park is all cram-full o' coal that the Castle folks won't allow us to dig, bad scran to them! Whin we get the bill we'll sink them mines an' send the Castle to blazes." The coal under the Phœnix Park is a matter of pious belief with every back-slum Dubliner. The gold of the Wicklow mountains is proverbial all over Ireland. There is not a nobleman's demesne that does not cover untold wealth in some shape or form. It may be gold, silver, copper, lead, or only coal or iron. But it is there, and the people of the neighbourhood want an Irish Parliament in order that the treasures may be turned into money. The more intelligent Nationalists foster these beliefs, although they know them to be without foundation. They know that the treasures do not exist in paying quantities, and also that if they did exist their fellow-countrymen are too lazy to dig them up. The Nationalist orators never rely on patriotic sentiment. They promise the land for nothing. Mr. William O'Brien has unceasingly offered as a bribe the promise of prairie rents for the farmers, but Tim Healy went one better when at Limerick he said that "The people of this country never ought to be satisfied so long as a single penny of rent is paid for a sod of land in the whole of Ireland." Well might Sir George Trevelyan say that Irish agitators have done much to demoralise the country, and that in many parts of Ireland they gained their livelihood by criminal agitation. The same authority tells us that "an Irish Parliament will be independent of the Parliament of this country, but will be dependent on the votes of the small farmers, who have been taught that rent is robbery." That is a precise statement of the position so far as the agricultural voters are concerned. Their patriotism is nothing more nor less than a sure and certain hope of pecuniary advantage. The green flag of Ireland has no charms for them. The ancient glories of Hibernia are sung to them in vain. They care not for the Onward march to Freedom. They will make no sacrifices on the shrine of their country. The subscriptions furnished by the Irish peasantry for the furtherance of the cause amount to almost nothing, although extorted partly by compulsion and partly by the hope of future profit. The following facts will show how spontaneous is their patriotism. At a Sunday meeting at Gurteen in 1887, the Very Reverend Canon O'Donohoe in the chair, it was resolved, "That a collection for the defence of Messrs. Dillon and O'Brien be made during the ensuing week in this locality, and that not less than sixpence be accepted from any person. Anyone not subscribing will be considered not in sympathy with the Branch." Those only who know Ireland well will be able to appreciate the terrible significance of the last sentence of this resolution, which for the information of the peasantry was made public in the Nationalist Sligo Champion. A similar incentive to patriotism seems to have been required by the Kilshelan Branch, for at another Sunday Meeting, the Reverend Father Dunphy in the chair, it was unanimously resolved, "That all members who do not pay in subscriptions on or before the next meeting, which will be held on the last Sunday of this month, shall have their names published and posted on the chapel gate for two consecutive Sundays." This quotation is from the Munster Express, published in Limerick. At a meeting reported by the Kerry Sentinel "the conduct of several members, who had not renewed their subscriptions, was strongly condemned, the reverend president, Father T. Enright, giving orders to have a list, with their names, sent to him before the next meeting." The chapel doors are used as instruments of boycotting. The priest sits in judgment on all who are not sufficiently patriotic. The people are compelled to subscribe to the cause, whether they like it or not. These cases could be multiplied to infinity. They not only give an excellent illustration of the conduct of the Irish clergy in political affairs, but they also furnish a curious commentary on the enthusiasm which is supposed to mark the Aspirations of a People, who, as Mr. Gladstone might say are "rightly struggling to be free." I have conversed with hundreds of Irish farmers and I never yet met one who was willing to sacrifice a sixpence on "the altar of his country," or to trust an Irish Parliament with his own property, or to invest a penny on purely Irish security. He loves his ease, no man likes it better, and No Rent means less exertion. Mr. O'Doherty, of County Donegal, a Catholic Home Ruler, said the landlords were all right now under compulsion, but what the tenantry demanded was to be released entirely from the landlords' yoke. The farmers, he said, cared nothing for Home Rule, but the Nationalists had preached prairie value, and the people expected to drive out the landowners and Protestants. Mr. John Cook, of Londonderry, a Protestant Home Ruler and a man of culture, did not claim patriotism for the Nationalists, and unconsciously put his finger on the real incentive when he said: – "The landlords will be wronged under the present bill. It is a bad bill, an unjust bill, and will do more harm than good. England should have a voice in fixing the price of the land, for if the matter be left to the Irish Parliament gross injustice will be done. The tenants were buying their land, aided by the English loans, for they found that their two-and-three-quarter per cent. interest came lower than their rent. But they have quite ceased to buy, because they expect the Irish Legislature to give them even better terms – or even to get the land for nothing." Patriotism had meanwhile received another sop. Mr. Healy advised the farmers to think twice before they bought their land, and hinted that their patience was likely to be well rewarded. Father J. Corcoran at Mullahoran, when consulted by a body of tenant farmers whose landlord offered to sell, distinctly advised them not to purchase, and gave a practical instruction on the subject, in which he endeavoured to prove that seventeen or eighteen years' purchase was at present unworthy of consideration, and advising the greatest caution in buying at all under present circumstances. The farmers' conception of Nationalism is plunder and confiscation. They vote for Home Rule because they thereby expect to make money, to become freeholders, landlords themselves, in short. They are taught that they have an inherent right to the land, and that an Irish Parliament will restore them their own. Father B. O'Hagan, addressing a meeting in company with William O'Brien, said: – "We have two classes of landlords, in brief. We have the royal scoundrels who took the land of our forefathers. I ask any of those noble ruffians to show me the title by which they lay claim to the soil of my ancestors. Then we have the landlords who have purchased their estates in the Land Courts. But they bought stolen goods, and they knew that the land was stolen. We must get rid of the landlords." Paddy is perfectly safe. The landlords who claim in descent and those who buy in the open market are equally denounced. Let him support the Nationalist party, and the land becomes his own. He does so, and his motive is by the unthinking called patriotism and by Mr. Gladstone the Aspirations of a People.