полная версия

полная версияMemorial Address on the Life and Character of Abraham Lincoln

The assassination of LINCOLN, who was so free from malice, has, by some mysterious influence, struck the country with solemn awe, and hushed, instead of exciting, the passion for revenge. It seems as if the just had died for the unjust. When I think of the friends I have lost in this war – and every one who hears me has, like myself, lost some of those whom he most loved – there is no consolation to be derived from victims on the scaffold, or from anything but the established union of the regenerated nation.

In his character LINCOLN was through and through an American. He is the first native of the region west of the Alleghanies to attain to the highest station; and how happy it is that the man who was brought forward as the natural outgrowth and first fruits of that region should have been of unblemished purity in private life, a good son, a kind husband, a most affectionate father, and, as a man, so gentle to all. As to integrity, Douglas, his rival, said of him: "Lincoln is the honestest man I ever knew."

The habits of his mind were those of meditation and inward thought, rather than of action. He delighted to express his opinions by an apothegm, illustrate them by a parable, or drive them home by a story. He was skilful in analysis, discerned with precision the central idea on which a question turned, and knew how to disengage it and present it by itself in a few homely, strong old English words that would be intelligible to all. He excelled in logical statement more than in executive ability. He reasoned clearly, his reflective judgment was good, and his purposes were fixed; but, like the Hamlet of his only poet, his will was tardy in action, and, for this reason, and not from humility or tenderness of feeling, he sometimes deplored that the duty which devolved on him had not fallen to the lot of another.

LINCOLN gained a name by discussing questions which, of all others, most easily lead to fanaticism; but he was never carried away by enthusiastic zeal, never indulged in extravagant language, never hurried to support extreme measures, never allowed himself to be controlled by sudden impulses. During the progress of the election at which he was chosen President he expressed no opinion that went beyond the Jefferson proviso of 1784. Like Jefferson and Lafayette, he had faith in the intuitions of the people, and read those intuitions with rare sagacity. He knew how to bide time, and was less apt to run ahead of public thought than to lag behind. He never sought to electrify the community by taking an advanced position with a banner of opinion, but rather studied to move forward compactly, exposing no detachment in front or rear; so that the course of his administration might have been explained as the calculating policy of a shrewd and watchful politician, had there not been seen behind it a fixedness of principle which from the first determined his purpose, and grew more intense with every year, consuming his life by its energy. Yet his sensibilities were not acute; he had no vividness of imagination to picture to his mind the horrors of the battle-field or the sufferings in hospitals; his conscience was more tender than his feelings.

LINCOLN was one of the most unassuming of men. In time of success, he gave credit for it to those whom he employed, to the people, and to the Providence of God. He did not know what ostentation is; when he became President he was rather saddened than elated, and his conduct and manners showed more than ever his belief that all men are born equal. He was no respecter of persons, and neither rank, nor reputation, nor services overawed him. In judging of character he failed in discrimination, and his appointments were sometimes bad; but he readily deferred to public opinion, and in appointing the head of the armies he followed the manifest preference of Congress.

A good President will secure unity to his administration by his own supervision of the various departments. LINCOLN, who accepted advice readily, was never governed by any member of his cabinet, and could not be moved from a purpose deliberately formed; but his supervision of affairs was unsteady and incomplete, and sometimes, by a sudden interference transcending the usual forms, he rather confused than advanced the public business. If he ever failed in the scrupulous regard due to the relative rights of Congress, it was so evidently without design that no conflict could ensue, or evil precedent be established. Truth he would receive from any one, but when impressed by others, he did not use their opinions till, by reflection, he had made them thoroughly his own.

It was the nature of LINCOLN to forgive. When hostilities ceased, he, who had always sent forth the flag with every one of its stars in the field, was eager to receive back his returning countrymen, and meditated "some new announcement to the South." The amendment of the Constitution abolishing slavery had his most earnest and unwearied support. During the rage of war we get a glimpse into his soul from his privately suggesting to Louisiana, that "in defining the franchise some of the colored people might be let in," saying: "They would probably help, in some trying time to come, to keep the jewel of liberty in the family of freedom." In 1857 he avowed himself "not in favor of" what he improperly called "negro citizenship," for the Constitution discriminates between citizens and electors. Three days before his death he declared his preference that "the elective franchise were now conferred on the very intelligent of the colored men, and on those of them who served our cause as soldiers;" but he wished it done by the States themselves, and he never harbored the thought of exacting it from a new government, as a condition of its recognition.

The last day of his life beamed with sunshine, as he sent, by the Speaker of this House, his friendly greetings to the men of the Rocky mountains and the Pacific slope; as he contemplated the return of hundreds of thousands of soldiers to fruitful industry; as he welcomed in advance hundreds of thousands of emigrants from Europe; as his eye kindled with enthusiasm at the coming wealth of the nation. And so, with these thoughts for his country, he was removed from the toils and temptations of this life, and was at peace.

Hardly had the late President been consigned to the grave when the prime minister of England died, full of years and honors. Palmerston traced his lineage to the time of the conqueror; LINCOLN went back only to his grandfather. Palmerston received his education from the best scholars of Harrow, Edinburg, and Cambridge; LINCOLN'S early teachers were the silent forest, the prairie, the river, and the stars. Palmerston was in public life for sixty years; LINCOLN for but a tenth of that time. Palmerston was a skilful guide of an established aristocracy; LINCOLN a leader, or rather a companion, of the people. Palmerston was exclusively an Englishman, and made his boast in the House of Commons that the interest of England was his Shibboleth; LINCOLN thought always of mankind, as well as his own country, and served human nature itself. Palmerston, from his narrowness as an Englishman, did not endear his country to any one court or to any one nation, but rather caused general uneasiness and dislike; LINCOLN left America more beloved than ever by all the peoples of Europe. Palmerston was self-possessed and adroit in reconciling the conflicting factions of the aristocracy; LINCOLN, frank and ingenuous, knew how to poise himself on the ever-moving opinions of the masses. Palmerston was capable of insolence towards the weak, quick to the sense of honor, not heedful of right;

LINCOLN rejected counsel given only as a matter of policy, and was not capable of being wilfully unjust. Palmerston, essentially superficial, delighted in banter, and knew how to divert grave opposition by playful levity; LINCOLN was a man of infinite jest on his lips, with saddest earnestness at his heart. Palmerston was a fair representative of the aristocratic liberality of the day, choosing for his tribunal, not the conscience of humanity, but the House of Commons; LINCOLN took to heart the eternal truths of liberty, obeyed them as the commands of Providence, and accepted the human race as the judge of his fidelity. Palmerston did nothing that will endure; LINCOLN finished a work which all time cannot overthrow. Palmerston is a shining example of the ablest of a cultivated aristocracy; LINCOLN is the genuine fruit of institutions where the laboring man shares and assists to form the great ideas and designs of his country. Palmerston was buried in Westminster Abbey by the order of his Queen, and was attended by the British aristocracy to his grave, which, after a few years, will hardly be noticed by the side of the graves of Fox and Chatham; LINCOLN was followed by tho sorrow of his country across the continent to his resting place in the heart of the Mississippi valley, to be remembered through all time by his countrymen, and by all the peoples of the world.

As the sum of all, the hand of LINCOLN raised the flag; the American people was the hero of the war; and, therefore, the result is a new era of republicanism. The disturbances in the country grew not out of anything republican, but out of slavery, which is a part of the system of hereditary wrong; and the expulsion of this domestic anomaly opens to the renovated nation a career of unthought-of dignity and glory. Henceforth our country has a moral unity as the land of free labor. The party for slavery and the party against slavery are no more, and are merged in the party of Union and freedom. The States which would have left us are not brought back as subjugated States, for then we should hold them only so long as that conquest could be maintained; they come to their rightful place under the Constitution as original, necessary, and inseparable members of the Union.

We build monuments to the dead, but no monuments of victory. We respect the example of the Romans, who never, even in conquered lands, raised emblems of triumph. And our generals are not to be classed in the herd of vulgar warriors, but are of the school of Timoleon, and William of Nassau, and Washington. They have used the sword only to give peace to their country and restore her to her place in the great assembly of the nations.

SENATORS AND REPRESENTATIVES of America: as I bid you farewell, my last words shall be words of hope and confidence; for now slavery is no more, the Union is restored, a people begins to live according to the laws of reason, and republicanism is intrenched in a continent.

APPENDIX

ABRAHAM LINCOLN was assassinated at 10.30 p.m. on the 14th of April, 1865, and died at 7.20 a.m. the next day. Congress was not in session, but a large number of members hastened to the Capitol on the receipt of the startling intelligence, and on the 17th a card was published by Senator Foot, inviting those Senators and Representatives who might be in the city the next day to meet at the Capitol, to consider what action they would take in relation to the funeral ceremonies.

The members of the 39th Congress then in Washington met in the Senate reception room, at the Capitol, on the 17th of April, 1865, at noon. Hon. LAFAYETTE S. FOSTER of Connecticut, President pro tem. of the Senate, was called to the chair, and the Hon. SCHUYLER COLFAX of Indiana, Speaker of the House in the 38th Congress, was chosen secretary.

Senator FOOT, of Vermont, who was visibly affected, stated that the object of the meeting was to make arrangements relative to the funeral of the deceased President of the United States.

On motion of Senator SUMNER, of Massachusetts, a committee of four members from each house was ordered to report at 4 p.m., what action would be fitting for the meeting to take. The Chairman appointed Senators Sumner of Massachusetts, Harris of New York, Johnson of Maryland, Ramsey of Minnesota, and Conness of California, and Representatives Washburne of Illinois, Smith of Kentucky, Schenck of Ohio, Pike of Maine, and Coffroth of Pennsylvania; and on motion of Mr. Schenck, the Chairman and Secretary of the meeting were added to the Committee, and then the meeting adjourned until 4 p.m.

The meeting re-assembled at 4 p.m., pursuant to adjournment.

Mr. SUMNER, from the Committee heretofore appointed, reported that they had selected as pall-bearers on the part of the Senate: Mr. Foster of Connecticut; Mr. Morgan of New York; Mr. Johnson of Maryland; Mr. Yates of Illinois; Mr. Wade of Ohio, and Mr. Conness of California. On the part of the House: Mr. Dawes of Massachusetts; Mr. Coffroth of Pennsylvania; Mr. Smith of Kentucky; Mr. Colfax of Indiana; Mr. Worthington of Nevada, and Mr. Washburne of Illinois. They also recommended the appointment of one member of Congress from each State and Territory to act as a Congressional Committee to accompany the remains of the late President to Illinois, and presented the following names as such Committee, the Chairman of the meeting to have the authority of appointing hereafter for the States and Territories not represented to-day from which members may be present at the Capitol by the day of the funeral:

Maine, Mr. Pike; New Hampshire, Mr. E. H. Rollins; Vermont, Mr. Foot; Massachusetts, Mr. Sumner; Rhode Island, Mr. Anthony; Connecticut, Mr. Dixon; New York, Mr. Harris Pennsylvania, Mr. Cowan; Ohio, Mr. Schenck; Kentucky, Mr. Smith; Indiana, Mr. Julian; Illinois, the delegation; Michigan, Mr. Chandler; Iowa, Mr. Harlan; California, Mr. Shannon; Minnesota, Mr. Ramsey; Oregon, Mr. Williams; Kansas, Mr. S. Clarke; West Virginia, Mr. Whaley; Nevada, Mr. Nye; Nebraska, Mr. Hitchcock; Colorado, Mr. Bradford; Dakota, Mr. Todd; Idaho, Mr. Wallace.

The Committee also recommended the adoption of the following resolution:

Resolved, That the Sergeants-at-Arms of the Senate and House with their necessary assistants be requested to attend the Committee accompanying the remains of the late President, and to make all the necessary arrangements.

All of which was concurred in unanimously.

Mr. SUMNER from the same Committee also reported the following, which was unanimously agreed to:

The members of the Senate and House of Representatives now assembled in Washington, humbly confessing their dependence upon Almighty God who rules all that is done for human good, make haste, at this informal meeting, to express the emotions with which they have been filled by the appalling tragedy which has deprived the Nation of its head and covered the land with mourning; and in further declaration of their sentiments unanimously resolve:

1. That in testimony of their veneration and affection for the illustrious dead, who has been permitted under Providence to do so much for his country and for liberty, they will unite in the funeral services, and by an appropriate Committee will accompany his remains to their place of burial in the State from which he was taken for the national service.

2. That in the life of Abraham Lincoln, who, by the benignant favor of Republican institutions, rose from humble beginnings to the heights of power and fame, they recognize an example of purity, simplicity and virtue, which should be a lesson, to mankind; while in his death they recognize a martyr, whose memory will become more precious as men learn to prize those principles of constitutional order and those rights, civil, political, and human, for which he was made a sacrifice.

3. That they invite the President of the United States, by solemn proclamation, to recommend to the people of the United States to assemble on a day to be appointed by him, publicly to testify their grief, and to dwell on the good which has been done on earth by him whom we now mourn.

4. That a copy of these resolutions be communicated to the President of the United States; and also, that a copy be communicated to the afflicted widow of the late President, as an expression of sympathy in her great bereavement.

The meeting then adjourned.

–The funeral ceremonies took place in the East room of the Executive Mansion, at noon, on the 19th of April, and the remains were then escorted to the Capitol, where they lay in state in the rotundo.

On the morning of April 21, the remains were taken from the Capitol and placed in a funeral car, in which they were taken to Springfield, Illinois, accompanied by the Congressional Committee. Halting at the principal cities along the route, that appropriate honors might be paid to the deceased, the funeral cortege arrived on the 3d of May at Springfield, Illinois, and the next day the remains were deposited in Oak Ridge cemetery near that city.

President JOHNSON, in his annual message to Congress at the commencement of the session of 1865-'66, thus announced the death of his predecessor:

"To express gratitude to God, in the name of the people, for the preservation of the United States, is my first duty in addressing you. Our thoughts next revert to the death of the late President by an act of parricidal treason. The grief of the nation is still fresh; it finds some solace in the consideration that-he lived to enjoy the highest proof of its confidence by entering on the renewed term of the Chief Magistracy to which he had been elected that he brought the civil war substantially to a close; that his loss was deplored in all parts of the Union; and that foreign nations have rendered justice to his memory."

Hon. E. B. WASHBURNE, of Illinois, immediately after the President's message had been read in the House of Representatives, offered the following wing joint resolution, which was unanimously adopted:

Resolved, That a committee of one member from each State represented in this House be appointed on the part of this House, to join such committee as may be appointed on the part of the Senate, to consider and report by what token of respect and affection it may be proper for the Congress of the United States to express tho deep sensibility of the nation to the event of the decease of their late President, Abraham Lincoln, and that so much of the message of the President as refers to that melancholy event be referred to said committee.

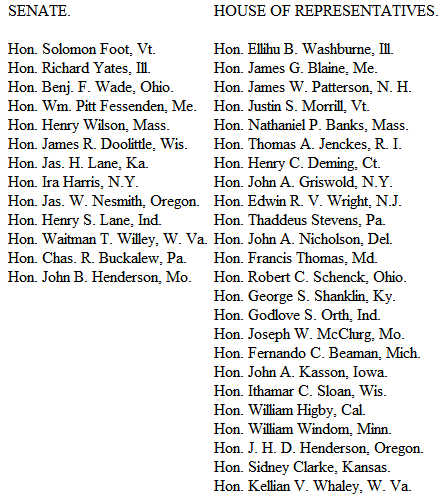

On motion of Hon. SOLOMON FOOT, the Senate unanimously concurred in the passage of the resolution, and the following joint committee was appointed – thirteen on the part of the Senate and one for every State represented (twenty-four) on the part of the House of Representatives:

That committee, by Hon. Mr. FOOT, made the following report, which was concurred in by both Houses nem. con.

Whereas the melancholy event of the violent and tragic death of Abraham Lincoln, late President of the United States, having occurred during the recess of Congress, and the two Houses sharing in the general grief and desiring to manifest their sensibility upon the occasion of the public bereavement: Therefore,

Be it resolved by the Senate, (the House of Representatives concurring,) That the two Houses of Congress will assemble in the Hall of the House of Representatives, on Monday, the 12th day of February next, that being his anniversary birthday, at the hour of twelve meridian, and that, in the presence of the two Houses there assembled, an address upon the life and character of Abraham Lincoln, late President of the United States, be pronounced by Hon. Edwin M. Stanton; and that the President of the Senate pro tempore and the Speaker of the House of Representatives be requested to invite the President of the United States, the heads of the several Departments, the judges of the Supreme Court, the representatives of the foreign governments near this Government, and such officers of the army and navy as have received the thanks of Congress who may then be at the seat of Government, to be present on the occasion.

And be it further resolved, That the President of the United States be requested to transmit a copy of these resolutions to Mrs. Lincoln, and to assure her of the profound sympathy of the two Houses of Congress for her deep personal affliction, and of their sincere condolence for the late national bereavement.

The Hon. GEORGE BANCROFT of New York, in response to an invitation from the joint committee, consented to deliver the address, (Mr. Stanton having previously declined.)

–On the morning of the 12th of February, 1865, the Capitol was closed to all except the members of Congress. At ten o'clock the doors leading to the rotundo were opened to those to whom tickets of admission had been extended, and the spacious galleries of the House of Representatives were soon crowded. The Speaker's desk was draped in mourning, and chairs were placed upon the floor for the invited guests.

At 12.30 p.m., the members of the Senate, following their President pro tempore and their Secretary, and preceded by their Sergeant-at-Arms, entered the Hall of the House of Representatives and occupied the seats reserved for them on the right and left of the main aisle.

The President pro tempore occupied the Speaker's chair, the Speaker of the House sitting at his left. The Chaplains of the Senate and of the House were seated on the right and left of the Presiding Officers of their respective Houses.

Shortly afterward the President of the United States, with the members of his Cabinet, entered the Hall and occupied seats, the President in front of the Speaker's table, and his Cabinet immediately on his right.

Immediately after the entrance of the President, the Chief Justice and the Associate Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States entered the Hall and occupied seats next to the President, on the right of the Speaker's table.

The others present were seated as follows:

The Heads of Departments, with the Diplomatic Corps, next to the President, on the left of the Speaker's table;

Officers of the Army and Navy, who, by name, have received the thanks of Congress, next to the Supreme Court, on the right of the Speaker's table;

Assistant Heads of Departments, Governors of States and Territories, and the Mayors of Washington and Georgetown, directly in the rear of the Heads of Departments;

The Chief Justice and Judges of the Court of Claims, and the Chief Justice and Associate Justices of the Supreme Court of the District of Columbia, directly in the rear of the Supreme Court;

The Heads of Bureaus in the Departments, directly in the rear of the officers of the Army and Navy;

Representatives on either side of the Hall, in the rear of those invited, four rows of seats on either side of the main aisles being reserved for Senators;

The Orator of the day, Hon. George Bancroft, at the table of the Clerk of the House;

The Chairmen of the Joint Committee of Arrangements, at the right and left of the orator, and next to them the Secretary of the Senate and the Clerk of the House;

The other officers of the Senate and of the House, on the floor at the right and the left of the Speaker's platform.

When order was restored, at twelve o'clock and twenty minutes p.m., the Marine band, stationed in the vestibule, played appropriate dirges.

Hon. LAFAYETE S. FOSTER, President pro tempore of the Senate, called the two Houses of Congress to order at 12.30.

Rev. DR. BOYNTON, Chaplain of the House, offered the following prayer:

Almighty God, who dost inhabit eternity, while we appear but for a little moment and then vanish away, we adore The Eternal Name. Infinite in power and majesty, and greatly to be feared art Thou. All earthly distinctions disappear in Thy presence, and we come before Thy throne simply as men, fallen men, condemned alike by Thy law, and justly cut off through sin from communion with Thee. But through Thy infinite mercy, a new way of access has been opened through Thy Son, and consecrated by His blood. We come, in that all-worthy Name, and plead the promise of pardon and acceptance through Him. By the imposing solemnities of this scene we are carried back to the hour when the nation heard, and shuddered at the hearing, that Abraham Lincoln was dead – was murdered. We would bow ourselves submissively to Him by whom that awful hour was appointed. We bow to the stroke that fell on the country in the very hour of its triumph, and hushed all its shouts of victory to one voiceless sorrow. "The Lord gave and the Lord hath taken away. Blessed be the name of the Lord." The shadow of that death has not yet passed from the heart of the nation, as this national testimonial bears witness to-day. The gloom thrown from these surrounding emblems of death is fringed, we know, with the glory of a great triumph, and the light of a great and good man's memory. Still, O Lord, may this hour bring to us the proper warning! "Be ye also ready; for in such an hour as ye think not, the Son of Man cometh." Any one of us may be called as suddenly as he whom we mourn.