полная версия

полная версияCurious Epitaphs, Collected from the Graveyards of Great Britain and Ireland.

[In one of our articles in Chambers’s Journal we furnished the foregoing sketch, and it has since been reproduced in many newspapers and in several volumes.]

In “Yorkshire Longevity,” compiled by Mr. William Grainge, of Harrogate, a most painstaking writer on local history, will be found an interesting account of Henry Jenkins, a celebrated Yorkshireman. It is stated: “In the year 1743, a monument was erected, by subscription, in Bolton churchyard, to the memory of Jenkins; it consists of a square base of freestone, four feet four inches on each side, by four feet six inches in height, surmounted by a pyramid eleven feet high. On the east side is inscribed: —

This monument waserected by contribution,in ye year 1743, to ye memoryof Henry JenkinsOn the west side: —

Henry Jenkins,Aged 169In the church, on a mural tablet of black marble, is inscribed the following epitaph, composed by Dr. Thomas Chapman, Master of Magdalen College, Cambridge: —

Blush not, marble,to rescue from oblivionthe memory ofHenry Jenkins:a person obscure in birth,but of a life truly memorable;forhe was enrichedwith the goods of nature,if not of fortune, and happyin the duration, if not variety,of his enjoyments:and,tho’ the partial world despised anddisregarded his low and humble state,the equal eye of Providencebeheld, and blessed itwith a patriarch’s health and length of days:to teach mistaken man,these blessings were entailed on temperance,or, a life of labour and a mind at easeHe lived to the amazing age of 169;was interred here, Dec. 6, (or 9,) 1670,and had this justice done to his memory 1743This inscription is a proof that learned men, and masters of colleges, are not always exempt from the infirmity of writing nonsense. Passing over the modest request to the black marble not to blush, because it may feel itself degraded by bearing the name of the plebeian Jenkins, when it ought only to have been appropriated to kings and nobles, we find but questionable philosophy in this inappropriate composition.

The multitude of great events which took place during the lifetime of this man are truly wonderful and astonishing. He lived under the rule of nine sovereigns of England – Henry VII.; Henry VIII.; Edward VI.; Mary; Elizabeth; James I.; Charles I.; Oliver Cromwell; and Charles II. He was born when the Roman Catholic religion was established by law. He saw the dissolution of the monasteries, and the faith of the nation changed – Popery established a second time by Queen Mary – Protestantism restored by Elizabeth – the Civil War between Charles and the Parliament begun and ended – Monarchy abolished – the young Republic of England, arbiter of the destinies of Europe – and the restoration of Monarchy under the libertine Charles II. During his time, England was invaded by the Scots; a Scottish King was slain, and a Scottish Queen beheaded in England; a King of Spain and a King of Scotland were Kings in England; three Queens and one King were beheaded in England in his days; and fire and plague alike desolated London. His lifetime appears like that of a nation, more than an individual, so long was it extended and so crowded was it with such great events.”

The foregoing many incidents remind us of the well-known Scottish epitaph on Marjory Scott, who died February 26th, 1728, at Dunkeld, at the extreme age of one hundred years. According to Chambers’s “Domestic Annals of Scotland,” the following epitaph was composed for her by Alexander Pennecuik, but never inscribed, and it has been preserved by the reverend statist of the parish, as a whimsical statement of historical facts comprehended within the life of an individual: —

Stop, passenger, until my life you read,The living may get knowledge from the dead.Five times five years I led a virgin life,Five times five years I was a virtuous wife;Ten times five years I lived a widow chaste,Now tired of this mortal life I rest.Betwixt my cradle and my grave hath beenEight mighty kings of Scotland and a queen.Full twice five years the Commonwealth I saw.Ten times the subjects rise against the law;And, which is worse than any civil war,A king arraigned before the subject’s bar.Swarms of sectarians, hot with hellish rage,Cut off his royal head upon the stage.Twice did I see old prelacy pulled down,And twice the cloak did sink beneath the gown.I saw the Stuart race thrust out; nay, more,I saw our country sold for English ore;Our numerous nobles, who have famous been,Sunk to the lowly number of sixteen.Such desolation in my days have been,I have an end of all perfection seen!A foot-note states: “The minister’s version is here corrected from one of the Gentleman’s Magazines for January 1733; but both are incorrect, there having been during 1728 and the one hundred preceding years no more than six kings of Scotland.”

In Scott’s “Tales of a Grandfather,” there is an account of the Battle of Lillyard’s Edge, which was fought in 1545. The spot on which the battle occurred is so called from an Amazonian Scottish woman, who is reported, by tradition, to have distinguished herself in the fight. An inscription which was placed on her tombstone was legible within the present century, and is said to have run thus: —

Fair Maiden Lillyard lies under this stane,Little was her stature, but great was her fame;Upon the English louns she laid many thumps,And when her legs were cutted off, she fought upon her stumps.The tradition says that a beautiful young lady, called Lillyard, followed her lover from the little village of Maxton, and when she saw him fall in battle, rushed herself into the heat of the fight, and was killed, after slaying several of the English.

On one of the buttresses on the south side of St. Mary’s Church, at Beverley, is an oval tablet, to commemorate the fate of two Danish soldiers, who, during their voyage to Hull, to join the service of the Prince of Orange, in 1689, quarrelled, and having been marched with the troops to Beverley, during their short stay there sought a private meeting to settle their differences by the sword. Their melancholy end is recorded in a doggerel epitaph, of which we give an illustration.

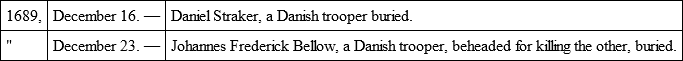

In the parish registers the following entries occur: —

In a note from the Rev. Jno. Pickford, M.A., we are told: “The mode of execution was, it may be presumed, by a broad two-handed sword, such a one as Sir Walter Scott has particularly described in “Anne of Geierstein,” as used at the decapitation of Sir Archibald de Hagenbach, “and which the executioner is described as wielding with such address and skill. The Danish culprit was, like the oppressive knight, probably bound and seated in a chair; but such swords as those depicted on the tablet could not well have been used for the purpose, for they are long, narrow in the blade, and perfectly straight.”

We have in the “Diary of Abraham de la Pryme,” the Yorkshire Antiquary, some very interesting particulars respecting the Danes. Writing in 1689, the diarist tells us: “Towards the latter end of the aforegoing year, there landed at Hull about six or seven thousand Danes, all stout fine men, the best equip’d and disciplin’d of any that was ever seen. They were mighty godly and religious. You would seldom or never hear an oath or ugly word come out of their mouths. They had a great many ministers amongst them, whome they call’d pastours, and every Sunday almost, ith’ afternoon, they prayed and preach’d as soon as our prayers was done. They sung almost all their divine service, and every ministre had those that made up a quire whom the rest follow’d. Then there was a sermon of about half-an-houre’s length, all memoratim, and then the congregation broke up. When they adminstered the sacrament, the ministre goes into the church and caused notice to be given thereof, then all come before, and he examined them one by one whether they were worthy to receive or no. If they were he admitted them, if they were not he writ their names down in a book, and bid them prepare against the next Sunday. Instead of bread in the sacrament, I observed that they used wafers about the bigness and thickness of a sixpence. They held it no sin to play at cards upon Sundays, and commonly did everywhere where they were suffered; for indeed in many places the people would not abide the same, but took the cards from them. Tho’ they loved strong drink, yet all the while I was amongst them, which was all this winter, I never saw above five or six of them drunk.”

The diarist tells us that the strangers liked this country. It appears they worked for the farmers, and sold tumblers, cups, spoons, &c., which they had imported, to the English. They acted in the courthouse a play in their own language, and realised a good sum of money by their performances. The design of the piece was “Herod’s Tyranny – The Birth of Christ – The Coming of the Wise Men.”

In Bolton churchyard, Lancashire, is a gravestone of considerable historical interest. It has been incorrectly printed in several books and magazines, but we are able to give a literal copy drawn from a carefully compiled “History of Bolton,” by John D. Briscoe: —

John Okey,The servant of God, was borne in London, 1608, came into this toune in 1629, married Mary, daughter of James Crompton, of Breightmet, 1635, with whom he lived comfortably 20 yeares, & begot 4 sons and 6 daughters. Since then he lived sole till the da of his death. In his time were many great changes, & terrible alterations – 18 yeares Civil Wars in England, besides many dreadful sea fights – the crown or command of England changed 8 times, Episcopacy laid aside 14 yeares; London burnt by Papists, & more stately built againe; Germany wasted 300 miles; 200,000 protestants murdered in Ireland, by the papists; this toune thrice stormed – once taken, & plundered. He went throw many troubles and divers conditions, found rest, joy, & happines only in holines – the faith, feare, and loue of God in Jesus Christ. He died the 29 of Ap and lieth here buried, 1684. Come Lord Jesus, o come quickly. Holiness is man’s happines.

[THE ARMS OF OKEY.]We gather from Mr. Briscoe’s history that Okey was a woolcomber, and came from London, to superintend some works at Bolton, where he married the niece of the proprietor, and died in affluence.

Bradley, the “Yorkshire Giant,” was buried in the Market Weighton church, and on a marble monument the following inscription appears: —

In memory ofWilliam Bradley,(Of Market Weighton,)Who died May 30th, 1820,Aged 33 yearsHe MeasuredSeven feet nine inches in Height,and Weighedtwenty-seven stonesIn “Celebrities of the Yorkshire Wolds,” by Frederick Ross, an interesting sketch of Bradley is given. Mr Ross states that he was a man of temperate habits, and never drank anything stronger than water, milk, or tea, and was a very moderate eater.

In Hampsthwaite churchyard was interred a “Yorkshire Dwarf.” Her gravestone states: —

In memory of Jane Ridsdale, daughter of George and Isabella Ridsdale, of Hampsthwaite, who died at Swinton Hall, in the parish of Masham, on the 2nd day of January, 1828, in the 59th year of her age. Being in stature only 31½ inches high.

Blest be the hand divine which gently laidMy head at rest beneath the humble shade;Then be the ties of friendship dear;Let no rude hand disturb my body here.In the burial-ground of St. Martin’s, Stamford, Lincolnshire, is a gravestone to Lambert of surprising corpulency: —

In remembrance of that prodigy in nature,Daniel Lambert,a native of Leicester,who was possessed of an excellent and convivial mind, andin personal greatness had no competitorHe measured three feet one inch round the leg, nine feet fourinches round the body, and weighed 52 stones 11lbs(14lb. to the stone)He departed this life on the 21st of June, 1809, aged 39 yearsAs a testimony of respect, this stone was erected by hisfriends in LeicesterRespecting the burial of Lambert we gather from a sketch of his life the following particulars: “His coffin, in which there was a great difficulty to place him, was six feet four inches long, four feet four inches wide, and two feet four inches deep; the immense substance of his legs made it necessarily a square case. This coffin, which consisted of 112 superficial feet of elm, was built on two axle-trees, and four cog-wheels. Upon these his remains were rolled into his grave, which was in the new burial ground at the back of St. Martin’s Church. A regular descent was made by sloping it for some distance. It was found necessary to take down the window and wall of the room in which he lay to allow of his being taken away.”

In St. Peter’s churchyard, Isle of Thanet, a gravestone bears the following inscription: —

In memory of Mr. Richard Joy called theKentish SamsonDied May 18th 1742 aged 67Hercules Hero Famed for StrengthAt last Lies here his Breadth and LengthSee how the mighty man is fallenTo Death ye strong and weak are all oneAnd the same Judgment doth BefallGoliath Great or David small.Joy was invited to Court to exhibit his remarkable feats of strength. In 1699 his portrait was published, and appended to it was an account of his prodigious physical power.

The next epitaph is from St. James’s cemetery, Liverpool: —

Reader pause. Deposited beneath are the remains ofSarah Biffin,who was born without arms or hands, at Quantox Head, County of Somerset, 25th of October, 1784, died at Liverpool, 2nd October, 1850. Few have passed through the vale of life so much the child of hapless fortune as the deceased: and yet possessor of mental endowments of no ordinary kind. Gifted with singular talents as an Artist, thousands have been gratified with the able productions of her pencil! whilst versatile conversation and agreeable manners elicited the admiration of all. This tribute to one so universally admired is paid by those who were best acquainted with the character it so briefly portrays. Do any inquire otherwise – the answer is supplied in the solemn admonition of the Apostle —

Now no longer the subject of tears,Her conflict and trials are o’er,In the presence of God she appears*****Our correspondent, Mrs. Charlotte Jobling, from whom we received the above, says: “The remainder is buried. It stands against the wall, and does not appear to now mark the grave of Miss Biffin.” Mr. Henry Morley, in his carefully prepared and entertaining “Memoirs of Bartholomew Fair,” writing about the fair of 1799, mentions Miss Biffin. “She was found,” says Mr. Morley, “in the Fair, and assisted by the Earl of Morton, who sat for his likeness to her, always taking the unfinished picture away with him when he left, that he might prove it to be all the work of her own shoulder. When it was done he laid it before George III., in the year 1808; obtained the King’s favour for Miss Biffin; and caused her to receive, at his own expense, further instruction in her art from Mr. Craig. For the last twelve years of his life he maintained a correspondence with her; and, after having enjoyed favour from two King Georges, she received from William IV. a small pension, with which, at the Earl’s request, she retired from a life among caravans. But fourteen years later, having been married in the interval, she found it necessary to resume, as Mrs. Wright, late Miss Biffin, her business as a skilful miniature painter, in one or two of our chief provincial towns.”

The following on Butler, the author of “Hudibras,” merits a place in our pages. The first inscription is from St. Paul’s, Covent Garden: —

Butler, the celebrated author of “Hudibras,” was buried in this church. Some of the inhabitants, understanding that so famous a man was there buried, and regretting that neither stone nor inscription recorded the event, raised a subscription for the purpose of erecting something to his memory. Accordingly, an elegant tablet has been put up in the portico of the church, bearing a medallion of that great man, which was taken from his monument in Westminster Abbey.

The following lines were contributed by Mr. O’Brien, and are engraved beneath the medallion: —

A few plain men, to pomp and pride unknown,O’er a poor bard have rais’d this humble stone,Whose wants alone his genius could surpass,Victim of zeal! the matchless “Hudibras.”What, tho’ fair freedom suffer’d in his page,Reader, forgive the author – for the age.How few, alas! disdain to cringe and cant,When ’tis the mode to play the sycophant.But oh! let all be taught, from Butler’s fate,Who hope to make their fortunes by the great;That wit and pride are always dangerous things,And little faith is due to courts or kings.The erection of the above monument was the occasion of this very good epigram by Mr. S. Wesley: —

Whilst Butler (needy wretch!) was yet alive,No gen’rous patron would a dinner give;See him, when starv’d to death and turn’d to dust,Presented with a monumental bust!The poet’s fate is here in emblem shown,He ask’d for bread, and he received a stone.It is worth remarking that the poet was starving, while his prince, Charles II., always carried a “Hudibras” in his pocket.

The inscription on his monument in the Abbey is as follows: —

Sacred to the Memory ofSamuel Butler,Who was born at Strensham, in Worcestershire, 1612, and died at London, 1680; a man of uncommon learning, wit, and probity: as admirable for the product of his genius, as unhappy in the rewards of them. His satire, exposing the hypocrisy and wickedness of the rebels, is such an inimitable piece, that, as he was the first, he may be said to be the last writer in his peculiar manner. That he, who, when living, wanted almost everything, might not, after death, any longer want so much as a tomb, John Barber, citizen of London, erected this monument 1721.

Here are a few particulars respecting an oddity, furnished by a correspondent: “Died, at High Wycombe, Bucks, on the 24th May, 1837, Mr. John Guy, aged 64. His remains were interred in Hughenden churchyard, near Wycombe. On a marble slab, on the lid of his coffin, is the following inscription: —

Here, without nail or shroud, doth lieOr covered by a pall, John GuyBorn May 17th, 1773Died – 24th, 1837On his grave-stone these lines are inscribed: —

In coffin made without a nail,Without a shroud his limbs to hide;For what can pomp or show avail,Or velvet pall, to swell the pride.Here lies John Guy beneath this sod,Who lov’d his friends, and fear’d his God.This eccentric gentleman was possessed of considerable property, and was a native of Gloucestershire. His grave and coffin were made under his directions more than a twelvemonth before his death; the inscription on the tablet on his coffin, and the lines placed upon his gravestone, were his own compositions. He gave all necessary orders for the conducting of his funeral, and five shillings were wrapped in separate pieces of paper for each of the bearers. The coffin was of singular beauty and neatness in workmanship, and looked more like a piece of tasteful cabinet work intended for a drawing-room, than a receptable for the dead.

Near the great door of the Abbey of St. Peter, Gloucester, says Mr. Henry Calvert Appleby, at the bottom of the body of the building, is a marble monument to John Jones, dressed in the robes of an alderman, painted in different colours. Underneath the effigy, on a tablet of black marble, are the following words: —

John Jones, alderman, thrice mayor of the city, burgess of the Parliament at the time of the gunpowder treason; registrar to eight several Bishops of this diocese.

He died in the sixth year of the reign of King Charles, on the first of June, 1630. He gave orders for his monument to be raised in his lifetime. When the workmen had fixed it up, he found fault with it, remarking that the nose was too red. While they were altering it, he walked up and down the body of the church. He then said that he had himself almost finished, so he paid off the men, and died the next morning.

The next epitaph from Newark, Nottinghamshire, furnishes a chapter of local history: —

Sacred to the memoryOf Hercules Clay, Alderman of Newark,Who died in the year of his Mayoralty,Jan. 1, 1644On the 5th of March, 1643,He and his family were preservedBy the Divine ProvidenceFrom the thunderbolt of a terrible cannonWhich had been levelled against his houseBy the Besiegers,And entirely destroyed the sameOut of gratitude for this deliverance,He has taken careTo perpetuate the remembrance thereofBy an alms to the poor and a sermon;By this meansRaising to himself a MonumentMore durable than BrassThe thund’ring Cannon sent forth from its mouth the devouring FlamesAgainst my Household Gods, and yours, O Newark.The Ball, thus thrown, Involved the House in Ruin;But by a Divine Admonition from Heaven I was saved,Being thus delivered by a strength Greater than that of Hercules,And having been drawn out of the deep Clay,I now inhabit the stars on high.Now, Rebel, direct thy unavailing Fires at Heaven,Art thou afraid to fight against God – thouWho hast been a Murderer of His People?Thou durst not, Coward, scatter thy FlamesWhilst Charles is lord of earth and skies.Also of his beloved wifeMary (by the gift of God)Partaker of the same felicity.Wee too made one by his decreeThat is but one in Trinity,Did live as one till death came inAnd made us two of one agen;Death was much blamed for our divorce,But striving how he might doe worseBy killing th’ one as well as th’ other,He fairely brought us both togeather,Our soules together where death dare not come,Our bodyes lye interred beneath this tomb,Wayting the resurrection of the just,O knowe thyself (O man), thou art but dust.1It is stated that Charles II., in a gay moment asked Rochester to write his epitaph. Rochester immediately wrote: —

Here lies the mutton-eating king,Whose word no man relied on;Who never said a foolish thing,Nor ever did a wise one.On which the King wrote the following comment: —

If death could speak, the king would say,In justice to his crown,His acts they were the minister’s,His words they were his own.Our friend, Mr. Thomas Broadbent Trowsdale, F.R.H.S., who has written much and well in history, folk-lore, etc., tells us: “In the fine old church of Chepstow, Monmouthshire, nearly opposite the reading desk, is a memorial stone with the following curious acrostic inscription, in capital letters: —

Here Sept. 9th, 1680,was buriedA True Born Englishman,Who, in Berkshire, was well knownTo love his country’s freedom ’bove his own:But being immured full twenty yearHad time to write, as doth appear —HIS EPITAPH.H ere or elsewhere (all’s one to you or me)E arth, Air, or Water gripes my ghostly dust,N one knows how soon to be by fire set free;R eader, if you an old try’d rule will trust,Y ou’ll gladly do and suffer what you must.M y time was spent in serving you and you,A nd death’s my pay, it seems, and welcome too;R evenge destroying but itself, while IT o birds of prey leave my old cage and fly;E xamples preach to the eye – care then, (mine says)N ot how you end, but how you spend your days.This singular epitaph points out the last resting place of Henry Marten, one of the judges who condemned King Charles I. to the scaffold. On the Restoration, Marten was sentenced to perpetual imprisonment, Chepstow Castle being selected as the place of his incarceration. There he died in 1680, in the twenty-eighth year of his captivity, and seventy-eighth of his age. He was originally interred in the chancel of the church; but a subsequent vicar of Chepstow, Chest by name, who carried his petty party animosities even beyond the grave, had the dead man’s dust removed, averring that he would not allow the body of a regicide to lie so near the altar. And so it was that Marten’s memorial came to occupy its present position in the passage leading from the nave to the north aisle. We are told that one, Mr. Downton, a son-in-law of this pusillanimous parson, touched to the quick by his relative’s harsh treatment of poor Marten’s inanimate remains, retorted by writing this satirical epitaph for the Rev. Mr. Chest’s tombstone: —

Here lies at rest, I do protest,One Chest within another!The chest of wood was very good, —Who says so of the other?Some doubt has been thrown on the probability of a man of Marten’s culture having written, as is implied in the inscription, the epitaph which has a place on his memorial.

The regicide was a son of Sir Henry Marten, a favourite of the first James, and by him appointed Principal Judge of the Admiralty and Dean of Arches. Young Henry was himself a prominent person during the period of the disastrous Civil War, and was elected Member of Parliament for Berkshire in 1640. He was, in politics, a decided Republican, and threw in his lot with the Roundhead followers of sturdy Oliver. When the tide of popular favour turned in Charles II.’s direction, and Royalty was reinstated, Marten and the rest of the regicides were brought to judgment for signing the death warrant of their monarch. The consequence, in Marten’s case, was life-long imprisonment, as we have seen, in Chepstow Castle.”