полная версия

полная версияThe Orchestral Conductor: Theory of His Art

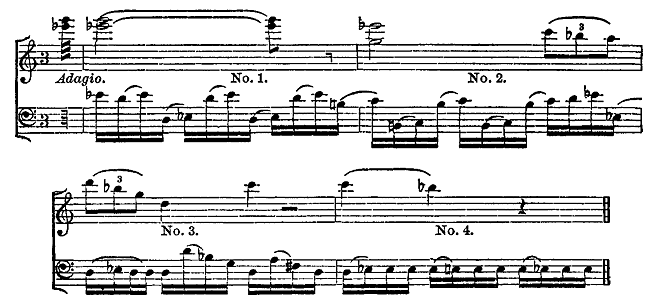

whereas the four previously maintained display the syncopation and make it better felt: —

This voluntary submission to a rhythmical form which the author intended to thwart is one of the gravest faults in style that a beater of the time can commit.

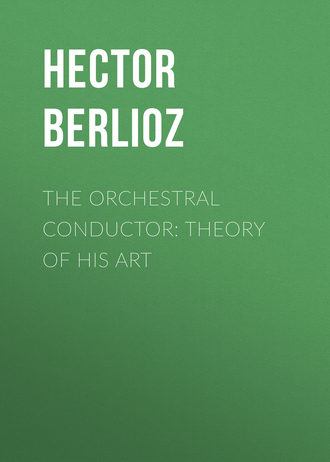

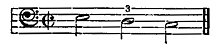

There is another dilemma, extremely troublesome for a conductor, and demanding all his presence of mind. It is that presented by the super-addition of different bars. It is easy to conduct a bar in dual time placed above or beneath another bar in triple time, if both have the same kind of movement. Their chief divisions are then equal in duration, and one needs only to divide them in half, marking the two principal beats: —

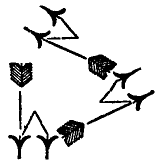

But if, in the middle of a piece slow in movement, there is introduced a new form brisk in movement, and if the composer (either for the sake of facilitating the execution of the quick movement, or because it was impossible to write otherwise) has adopted for this new movement the short bar which corresponds with it, there may then occur two, or even three short bars super-added to a slow bar: —

Bar No. 1.

Bars Nos. 2, 3, and so on.

The conductor's task is to guide and keep together these different bars of unequal number and dissimilar movement. He attains this by dividing the beats in the andante bar, No. 1, which precedes the entrance of the allegro in 6⁄8, and by continuing to divide them; but taking care to mark the division more decidedly. The players of the allegro in 6⁄8 then comprehend that the two gestures of the conductor represent the two beats of their short bar, while the players of the andante take these same gestures merely for a divided beat of their long bar.

It will be seen that this is really quite simple, because the division of the short bar, and the subdivisions of the long one, mutually correspond. The following example, where a slow bar is super-added to the short ones, without this correspondence existing, is more awkward: —

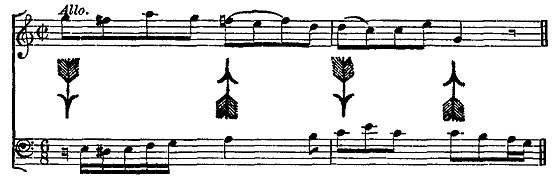

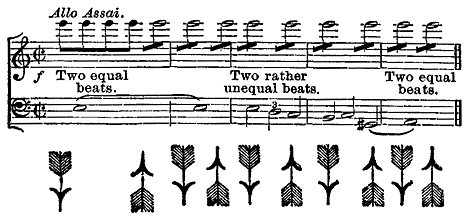

Here, the three bars allegro-assai preceding the allegretto are beaten in simple two time, as usual. At the moment when the allegretto begins, the bar of which is double that of the preceding, and of the one maintained by the violas, the conductor marks two divided beats for the long bar, by two equal gestures down, and two others up: —

The two large gestures divide the long bar in half, and explain its value to the hautboys, without perplexing the violas, who maintain the brisk movement, on account of the little gesture which also divides in half their short bar.

From bar No. 3, the conductor ceases to divide thus the long bar by 4, on account of the triple rhythm of the melody in 6⁄8, which this gesture interferes with. He then confines himself to marking the two beats of the long bar; while the violas, already launched in their rapid rhythm, continue it without difficulty, comprehending exactly that each stroke of the conductor's stick marks merely the commencement of their short bar.

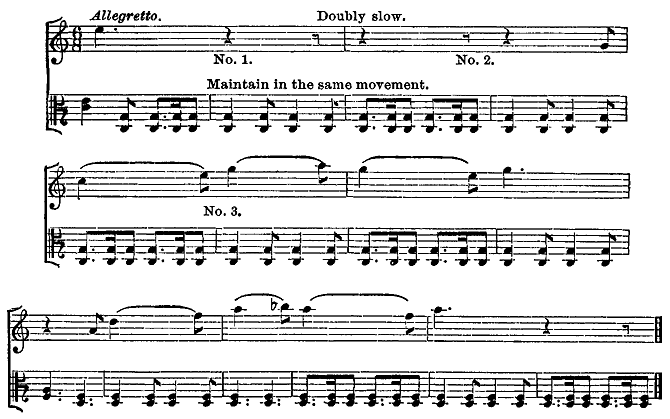

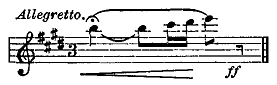

This last observation shows with what care dividing the beats of a bar should be avoided when a portion of the instruments or voices has to execute triplets upon these beats. The division, by cutting in half the second note of the triplet, renders its execution uncertain. It is even necessary to abstain from this division of the beats of a bar just before the moment when the rhythmical or melodic design is divided by three, in order not to give to the players the impression of a rhythm contrary to that which they are about to hear: —

In this example, the subdivision of the bar into six, or the division of beats into two, is useful; and offers no inconvenience during bar No. 1, when the following gesture is made: —

But from the beginning of bar No. 2 it is necessary to make only the simple gestures: —

on account of the triplet on the third beat, and on account of the one following it which the double gesture would much interfere with.

In the famous ball-scene of Mozart's Don Giovanni, the difficulty of keeping together the three orchestras, written in three different measures, is less than might be thought. It is sufficient to mark downwards each beat of the tempo di minuetto: —

Once entered upon the combination, the little allegro in 3⁄8, of which a whole bar represents one-third, or one beat of that of the minuetto, and the other allegro in 2⁄4, of which a whole bar represents two-thirds, or two beats, correspond with each other and with the principal theme; while the whole proceeds without the slightest confusion. All that is requisite is to make them come in properly.

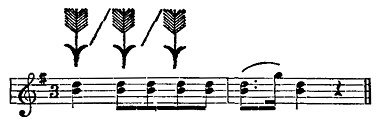

A gross fault that I have seen committed, consists in enlarging the time of a piece in common-time, when the author has introduced into it triplets of minims: —

In such a case, the third minim adds nothing to the duration of the bar, as some conductors seem to imagine. They may, if they please, and if the movement be slow or moderate, make these passages by beating the bar with three beats, but the duration of the whole bar should remain precisely the same. In a case where these triplets occur in a very quick bar in common-time (allegro-assai), the three gestures then cause confusion, and it is absolutely necessary to make only two, – one beat upon the first minim, and one upon the third. These gestures, owing to the quickness of the movement, differ little to the eye, from the two of the bar with two equal beats, and do not affect the movement of those parts of the orchestra which contain no triplets.

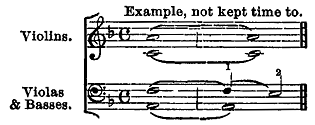

We will now speak of the conductor's method of beating in recitatives. Here, as the singer or the instrumentalist is reciting, and no longer subject to the regular division of the bar, it is requisite, while following him attentively, to make the orchestra strike, simultaneously and with precision, the chords or instrumental passages with which the recitative is intermingled; and to make the harmony change at the proper instant, when the recitative is accompanied either by holding-notes or by a tremolo in several parts, of which the least apparent, occasionally, is that which the conductor must most regard, since upon its motion depends the change of chord: —

In this example, the conductor, while following the reciting part, not kept time to, has especially to attend to the viola part, and to make it move, at the proper moment, from the F to the E, at the commencement of the second bar; because otherwise, as this part is executed by several instrumentalists playing in unison, some of them would hold the F longer than the rest, and a transient discord would be produced.

Many conductors have the habit, when directing the orchestra in recitatives, of paying no heed to the written division of the bar, and of marking an up beat before that whereon a brief orchestral chord occurs, even when this chord comes on an unaccented part of the bar: —

In a passage such as this, they raise the arm at the rest which commences the bar, and lower it at the time of the chord.

I cannot approve of such a method, which nothing justifies, and which may frequently occasion accidents in the execution. Neither do I see why, in recitatives, the bar should not be divided regularly, and the real beats marked in their place, as in music beaten in time. I therefore advise – for the preceding example – that the first beat should be made down, as usual, and the stick carried to the left for striking the chord upon the second beat; and so on for analogous cases; always dividing the bar regularly. It is very important, moreover, to divide it according to the time previously indicated by the author, and not to forget, – if this time is allegro or maestoso, and if the reciting part has been some time reciting unaccompanied, – to give to all the beats, when the orchestra comes in again, the value of those of an allegro or of a maestoso. For when the orchestra plays alone, it does so generally in time; it plays without measured time only when it accompanies a voice or instrument in recitative.

In the exceptional case where the recitative is written for the orchestra itself, or for the chorus, or for a portion of either orchestra or chorus, it being then requisite to keep together, whether in unison or in harmony, but without regular time, a certain number of performers, the conductor himself becomes the real reciter, and gives to each beat of the bar the duration he judges fit. According to the form of the phrase, he divides and subdivides the beats, now marks the accents, now the semiquavers, if there are any, and, in short, indicates with his stick the melodic form of the recitative.

It must of course be understood that the performers, knowing their parts almost by heart, keep their eye constantly upon him, otherwise, neither security nor unity can be obtained.

In general, even for timed music, the conductor should require the players he directs to look towards him as often as possible.

An orchestra which does not watch the conducting-stick has no conductor. Often, after a pedal-point for instance, the conductor is obliged to refrain from marking the decisive gesture which is to determine the coming in of the orchestra until he sees the eyes of all the performers fixed upon him. It is the duty of the conductor, during rehearsal, to accustom them to look towards him simultaneously at the important moment.

If the rule just indicated were not observed in the above bar, of which the first beat, marking a pedal-point, may be prolonged indefinitely, the passage —

could not be uttered with firmness and unity; the players, not watching the conductor's stick, could not know when he decides the second beat and resumes the movement suspended by the pedal-point.

The obligation upon the performers to look at their conductor necessarily implies an equal obligation on his part to let himself be well seen by them. He should, – whatever may be the disposal of the orchestra, whether on rows of steps, or on a horizontal plane, – place himself so as to form the centre of all surrounding eyes.

To place himself well in sight, a conductor requires an especial platform, elevated in proportion as the number of performers is large and occupies much space. His desk should not be so high that the portion sustaining the score shall hide his face for the expression of his countenance has much to do with the influence he exercises. If there is no conductor for an orchestra that does not and will not watch him, neither is there any if he cannot be well seen.

As to the employment of noises of any kind whatever, produced by the stick of the conductor upon his desk, or by his foot upon the platform, they call for no other than unreserved reprehension. It is worse than a bad method; it is a barbarism. In a theatre, however, when the stage evolutions prevent the chorus-singers from seeing the conducting-stick, the conductor is compelled – to ensure, after a pause, the taking up a point by the chorus – to indicate this point by marking the beat which precedes it by a slight tap of his stick upon the desk. This exceptional circumstance is the only one which can warrant the employment of an indicating noise, and even then it is to be regretted that recourse must be had to it.

While speaking of chorus-singers, and of their operations in theatres, it may here be observed that chorus-masters often allow themselves to beat time at the side-scenes, without seeing the conductor's stick, frequently even without hearing the orchestra. The result is that this time, beaten more or less ill, and not corresponding with that of the conductor, inevitably induces a rhythmical discordance between the choral and instrumental bodies, and subverts all unity instead of tending to maintain it.

There is another traditional barbarism which lies within the province of an intelligent and active conductor to abolish. If a choral or instrumental piece is performed behind the scenes, without accompaniment from the principal orchestra, another conductor is absolutely essential. If the orchestra accompany this portion, the first conductor, who hears the distant music, is then strictly bound to let himself be guided by the second, and to follow his time by ear. But if – as frequently happens in modern music – the sound of the chief orchestra hinders the conductor from hearing that which is being performed at a distance from him, the intervention of a special conducting mechanism becomes indispensable, in order to establish instantaneous communication between him and the distant performers. Many attempts, more or less ingenious, have been made of this kind, the result of which has not everywhere answered expectations. That of Covent Garden Theatre, in London, moved by the conductor's foot, acts tolerably well. But the electric metronome, set up by Mr. Van Bruge in the Brussels Theatre, leaves nothing to be desired. It consists of an apparatus of copper ribbons, leading from a Voltaic battery placed beneath the stage, attached to the conductor's desk, and terminating in a movable stick fastened at one end on a pivot before a board at a certain distance from the orchestral conductor. To this latter's desk is affixed a key of copper, something like the ivory key of a pianoforte; it is elastic, and provided on the interior side with a protuberance of about a quarter of an inch long. Immediately beneath this protuberance is a little cup, also of copper, filled with quicksilver. At the instant when the orchestral conductor, desiring to mark any particular beat of a bar, presses the copper key with the forefinger of his left hand (his right being occupied in holding, as usual, the conducting-stick) this key is lowered, the protuberance passes into the cup filled with quicksilver, a slight electric spark is emitted, and the stick placed at the other extremity of the copper ribbon makes an oscillation before its board. The communication of the fluid and the movement are quite simultaneous, no matter how great a distance is traversed.

The performers being grouped behind the scenes, their eyes fixed upon the stick of the electric metronome, are thus directly subject to the conductor, who could, were it needful, conduct, from the middle of the Opera orchestra in Paris, a piece of music performed at Versailles.

It is merely requisite to agree upon beforehand with the chorus-singers, or with their conductor (if as an additional precaution, they have one), the way in which the orchestral conductor beats the time – whether he marks all the principal beats, or, only the first of the bar – since the oscillations of the stick, moved by electricity, being always from right to left, indicate nothing precise in this respect.

When I first used, at Brussels, the valuable instrument I have just endeavored to describe, its action presented one objection. Each time that the copper key of my desk underwent the pressure of my left forefinger, it struck, underneath, another plate of copper, and, notwithstanding the delicacy of the contact, produced a little sharp noise, which, during the pauses of the orchestra, attracted the attention of the audience, to the detriment of the musical effect.

I pointed out the fault to Mr. Van Bruge, who substituted for the lower plate of copper the little cup filled with quicksilver, previously mentioned. Into this the protuberance so entered as to establish the electric current without causing the slightest noise.

Nothing remains now, as regards the use of this mechanism, but the crackling of the spark at the moment of its emission. This, however, is too slight to be heard by the public.

The metronome is not expensive to put up; it costs £16 at the most. Large lyric theatres, churches, and concert-rooms should long ago have been provided with one. Yet, save at the Brussels Theatre, it is nowhere to be found. This would appear incredible, were it not that the carelessness of the majority of directors of institutions where music forms a feature is well known; as are their instinctive aversion to whatever disturbs old-established customs, their indifference to the interests of art, their parsimony wherever an outlay for music is needed, and the utter ignorance of the principles of our art among those in whose hands rests the ordering of its destiny.

I have not yet said all on the subject of those dangerous auxiliaries named chorus-masters. Very few of them are sufficiently versed in the art, to conduct a musical performance, so that the orchestral conductor can depend upon them. He cannot therefore watch them too closely when compelled to submit to their coadjutorship.

The most to be dreaded are those whom age has deprived of activity and energy. The maintenance of vivacious times is an impossibility to them. Whatever may be the degree of quickness indicated at the head of a piece confided to their conducting, little by little they slacken its pace, until the rhythm is reduced to a certain medium slowness, that seems to harmonize with the speed at which their blood flows, and the general feebleness of their organization.

It must in truth be added, that old men are not the only ones with whom composers run this risk. There are men in the prime of life, of a lymphatic temperament, whose blood seems to circulate moderato. If they have to conduct an allegro assai, they gradually slacken it to moderato; if, on the contrary, it is a largo or an andante sostenuto, provided the piece is prolonged, they will, by dint of progressive animation, attain a moderato long before the end. The moderato is their natural pace, and they recur to it as infallibly as would a pendulum after having been a moment hurried or slackened in its oscillations.

These people are the born enemies of all characteristic music, and the greatest destroyers of style. May Fate preserve the orchestral conductor from their co-operation.

Once, in a large town (which I will not name), there was to be performed behind the scenes a very simple chorus, written in 6⁄8, allegretto. The aid of the chorus-master became necessary. He was an old man.

The time in which this chorus was to be taken having been first agreed upon by the orchestra, our Nestor followed it pretty decently during the first few bars; but, soon after, the slackening became such that there was no continuing without rendering the piece perfectly ridiculous. It was recommenced twice, thrice, four times; a full half-hour was occupied in ever-increasingly vexatious efforts, but always with the same result. The preservation of allegretto time was absolutely impossible to the worthy man. At last the orchestral conductor, out of all patience, came and begged him not to conduct at all; he had hit upon an expedient: – He caused the chorus-singers to simulate a march-movement, raising each foot alternately, without moving on. This movement, being in exactly the same time as the dual rhythm of the 6⁄8 in a bar, allegretto, the chorus-singers, who were no longer hindered by their director, at once performed the piece as though they had sung marching; with no less unity than regularity, and without slackening the time.

I acknowledge, however, that many chorus-masters, or sub-conductors of orchestras, are sometimes of real utility, and even indispensable for the maintenance of unity among very large masses of performers. When these masses are obliged to be so disposed as that one portion of the players or chorus-singers turn their back on the conductor, he needs a certain number of sub-beaters of the time, placed before those of the performers who cannot see him, and charged with repeating all his signals. In order that this repetition shall be precise, the sub-conductors must be careful never to take their eyes off the chief conductor's stick for a single instant. If, in order to look at their score, they cease to watch him for only three bars, a discrepancy arises immediately between their time and his, and all is lost.

In a festival where 1200 performers were assembled under my direction, at Paris, I had to employ four chorus-masters, stationed at the four corners of the vocal mass, and two sub-conductors, one of whom directed the wind-instruments, and the other the instruments of percussion. I had earnestly besought them to look towards me incessantly; they did not omit to do so, and our eight sticks, rising and falling without the slightest discrepancy of rhythm, established amidst our 1200 performers the most perfect unity ever witnessed.

With one or more electric metronomes, it seems no longer necessary to have recourse to this means. One might, in fact, thus easily conduct chorus-singers who turn their back towards the chief conductor; but attentive and intelligent sub-conductors are always preferable to a machine. They have not only to beat the time, like the metronomic staff, but they have also to speak to the groups around them, to call their attention to nice shades of execution, and, after bar-rests, to remind them when the moment of their re-entry comes.

In a space arranged as a semicircular amphitheatre, the orchestral conductor may conduct a considerable number of performers alone, all eyes then being able to look towards him. Nevertheless, the employment of a certain number of sub-conductors appears to me preferable to individual direction, on account of the great distance between the chief conductor and the extreme points of the vocal and instrumental body.

The more distant the orchestral conductor is from the performers he directs, the more his influence over them is diminished.

The best way would be to have several sub-conductors, with several electric metronomes beating before their eyes the principal beats of the bar.

And now, – should the orchestral conductor give the time standing or sitting down?

If, in theatres where they perform scores of immense length, it is very difficult to endure the fatigue of remaining on foot the whole evening, it is none the less true that the orchestral conductor, when seated, loses a portion of his power, and cannot give free course to his animation, if he possess any.

Then, should he conduct reading from a full score, or from a first violin part (leader's copy), as is customary in some theatres? It is evident that he should have before him a full score. Conducting by means of a part containing only the principal instrumental cues, the bass and the melody, demands a needless effort of memory from a conductor; and moreover, if he happens to tell one of the performers, whose part he cannot examine, that he is wrong, exposes him to the chance of the reply: “How do you know?”