полная версия

полная версияOperas Every Child Should Know

"Truly the young knight is a poet," he mused. Hans himself was a true poet, tender and loving, and he could think of nothing but Eva's good. Becoming nervous and apprehensive while thinking of her he began to hammer at a shoe, but again he ceased to work and tried to think. "I still hear that strain of the young knight's" and he tried to recall some part of the song. While he mused thus alone, Eva stole shyly over to the shop. It had now become quite dark and the neighbours were going to bed.

"Good evening, Master Sachs! You are still at work?" she asked softly. Hans started.

"Yes, my child, my dear Evchen. I am still at work. Why are you still awake? Ah, I know – it is about your fine new shoes that you have come, those for to-morrow!"

"Nay, they look so rich and fine, I have not even tried them on."

"Yet to-morrow you must wear them as a bride, you know."

"Whose shoes are these that you work upon, Master Sachs," she asked, wishing to change the subject.

"These are the shoes of the great Master Beckmesser," Sachs answered, smiling a little at the thought of the bumptious old fellow.

"In heaven's name put plenty of pitch in them, that he may stick, and not be able to come after me," she cried.

"What – you do not favour Beckmesser, then?"

"That silly old man," she said scornfully.

"Well, there is a very scanty batch of bachelors to sue for thee, or sing for thee," Hans answered, looking lovingly at her, with a little smile.

"Well, there are some widowers," Eva said returning his friendly look. Hans laughed outright.

"Ah, dear Evchen, it is not for an old chap like me to snare a young bird like thee. At the trial to-day, things did not go well," he ventured, trying to turn the conversation.

Instantly Eva was all attention, and she got from him the story of Walther's failure and unfair treatment, just as Magdalene called from the house over the way.

"St – st," she whispered. "Thy father has called for thee."

"I'll come presently," Eva answered. Then to Hans: "But tell me, dear Hans, was there not one who was his friend? Is there no hope?"

"No master has hope among other masters," Hans replied, sorrowfully. "I fear there is nothing for him but to give thee up." Hans knew well that Eva loved the knight.

"What man has a friend, whose own greatness makes other men feel small?" he asked still more sadly. "It is the way with men."

"It is shameful," she cried angrily, and hurried across the street. Hans closed the upper half of his door, so that he was almost shut in, and only a little light showed through.

"Eva," Magdalene called at the house door, "that Beckmesser has been here to say he is coming to serenade you, and to win your love. Did ever one hear of such a ridiculous rascal."

"I will not hear him," Eva declared angrily. "I will not. I am going to see Walther to-night, and I will not see Beckmesser. Look out and see if any one is coming." Walther was at that moment coming round the corner of the path, and Eva rushed toward him.

"You have heard – that I may not sing to win thee?" he said under his breath, for fear Pogner should hear him. At that moment the horn of the Night Warder was heard, which assured them that the town was all quiet and people gone to bed.

"It does not matter, I have made up my mind. I will never give the victor's crown to any one but thee, and so we shall flee together – this night, at once, before it is too late." Walther, beside himself with joy, looked after her while she hurried into the house to get ready for flight. The Night Warder came round the house corner.

Hear all folk, the Warder's ditty,'Tis ten o'clock in our city;Heed well your fire and eke your light,That none may be harmed this night!Praise ye God, the Lord!He blew a long loud blast upon his trumpet.

Hans Sachs had heard the plan concocted between the lovers, from behind his nearly closed door; so he put out the lamp, that he might not be seen, and opened his door a little way. He could never permit them to elope; it would cause no end of trouble. After a moment Eva and Magdalene came from Pogner's house with a bundle, while at the same moment Walther came from the shadow of the lime tree to meet them. They were hurrying off together when the clever shoemaker caught up his lamp from its place of concealment and turned it full upon the alley-way, so that it shone directly upon the path of the lovers.

Eva and Walther found themselves standing together in a bright light, when they had thought to escape unseen in the darkness. Again the Warder's horn was heard at a distance.

"Oh, good gracious! We shall be caught," Eva whispered, frightened half to death, as Walther drew her out of the streaming light.

"Which way shall we go?" he whispered, uneasily.

"Alas! look there – at that old rascal, Beckmesser," she returned, distracted with fright and anger, as she saw the old fool come in sight with his lute strung over his shoulder, while he twanged it lightly.

The moment Hans saw Beckmesser he had a new thought. He withdrew the light a little and opened the door. Then in the half light he placed his bench in the doorway and began to work upon a pair of shoes.

"It is that horrible Marker who counted me out this morning," Walther murmured, looking at Beckmesser as he stole along the pathway. Then almost at once, Beckmesser began to bawl under Eva's window.

He looked up where he supposed her to be, in the most languishing manner, so that Walther and Eva would have laughed outright, if they had not been in such a coil.

He no sooner had struck the first notes, than Hans Sachs gave a bang upon his shoe-last. Thus began an awful scrimmage. Hans Sachs, disliking the absurd old Beckmesser as much, if not more, than others did, banged away at Beckmesser's shoes, in a most energetic way. He made such a frightful din that Beckmesser could hardly hear himself sing.

The town clerk tried by every device to stop the shoemaker, – to get him to put aside his cobbling for the night, but Hans answered that he had to work lively if he hoped to get the shoes done for the fête. Beckmesser did not dare tell why he was there, singing at that hour. Walther and Eva remained prisoners under the lime tree, wondering what on earth to do. After a while, poor Beckmesser, making the most frantic efforts to hear his own voice, pleaded with Hans to stop.

"I'll tell thee what to do – it will make the time pass pleasantly for me as well, you see," Hans cried. "Do thou go ahead and sing, and I'll be Marker. For every mistake of thine, I'll hammer the shoe. Of course there will be so few mistakes that there will then be but little pounding." Beckmesser caught at that suggestion. Of course it was imprudent, but then Beckmesser was in a bad way, and it was his only chance. So he began his serenade once more. Then Hans began to "mark" him. Before he had sung a line, Hans's hammer was banging away in the most remarkable manner. Even Walther and Eva had to laugh, frightened as they were. Beckmesser became so furious he could hardly speak. Sachs pretended to see nothing, and "marked" away valiantly. Then the Night Watch could be heard coming. Hans banged louder. Beckmesser put his fingers in his ears, that he might drown the sound of Hans and the Warder, and keep on the key. Hans too began to sing as he waxed his threads and banged upon his shoes. Meantime windows were going up, the people who had gone to bed having wakened.

"Stop your bawling there," one shouted.

"Leave off howling," another screamed.

"What's the matter? Have you gone crazy down there," others yelled, but Beckmesser still shrieked, unable to hear anybody but himself and Hans.

"Listen to that donkey bray," a neighbour called.

"Hear the wild-cat," another bawled; and in the midst of the singing Magdalene stuck her head out of the window. Beckmesser, thinking it was Eva, was encouraged to keep on, but David, who had come out at the rumpus, believed that Beckmesser was serenading Magdalene, and instantly became jealous. So out he rushed with a cudgel. The neighbours then began to come from their houses in their night-gowns and caps; some wearing red flannel about their heads and some in very short gowns, and all looking very funny. Meanwhile, Hans, who had got the row started, withdrew into his house and shut the door. Walther and Eva were still trembling under the lime tree, sure of being discovered, now that all Nuremberg was aroused and on the spot.

Beckmesser was surrounded by the neighbours, the apprentices came from every shop to swell the crowd, also the journeymen, while all the women bawled from the house windows where they were hanging out half way. David and Beckmesser were wrestling all over the place, Beckmesser's lute being smashed and his clothes torn off him. At last the Mastersingers themselves arrived.

Walther, at last deciding that the time had come when he must rescue Eva, drew his sword and rushed forth. Hans, who had been watching behind his door, then ran out, pushed his way through the mob and caught Walther by the arm. At that moment – Poof! Bist! the women in the windows threw down buckets of water over all the people, and Beckmesser was half drowned in the streams. This added to the confusion, so that Hans grasped Walther, and Pogner his daughter; Sachs and Walther retired into Sachs's house and Eva was dragged within her own. As Sachs disappeared, he gave David a kick which sent him flying, to pay him for his part in the fight.

Beckmesser, battered half to pieces, limped off, while the crowd, dripping wet and with ardour cooled, slunk out. When all was perfectly quiet and safe, and not a sound stirring, on came the Night Warder. It was comical to see the way he looked all about the deserted place, as if he had been taking a little nap, while all Nuremberg had been fighting like wild-cats, and he quavered out in a shaky voice:

Hear, all folks, the Warder's ditty,Eleven strikes in our city,Defend yourselves from spectre and sprite,That no evil imp your soul affright.He finished with a long-drawn cry:

Praise ye God, the Lord,and all was still.

ACT IIIThe morning of the song festival dawned clear and fine. Early in the morning, Hans Sachs seated himself in his shop, beside his sunny window, his work on the bench before him, but he let it go unheeded as he fell to reading. David found his master thus employed when he stole into the shop, after peeping to make sure that Hans would pay no attention to him. David was not at all sure of the reception his master would give him after the riot in which he had taken a hand the night before. As Hans did not look up, David set the basket he carried upon the table, and began to take out the things in it. First there were flowers and bright-coloured ribbons, and at the very bottom a cake and a sausage. He was just beginning to eat the sausage when Hans Sachs turned a page of his book noisily. David, knowing his guilty part in the fight, looked warily at his master.

"Master, I have taken the shoes to Beckmesser and – " Sachs looked at him abstractedly.

"Do not disturb our guest, Sir Walther," he said, seeming to forget David's misbehaviour. "Eat thy cakes and be happy – only do not wake our guest."

Soon David went out while Sachs still sat thinking of the situation and half decided to take a part in the contest himself – since it were a shame to have Beckmesser win Eva. While he was thus lost in contemplation, Walther woke and came from his room.

"Ah, dear Hans – I have had a glorious dream," he cried. "It is so splendid that I hardly dare think of it."

"Can it be thou hast dreamed a song?" Sachs asked breathlessly.

"Even if I had, what help would it bring me, friend Sachs, since the Mastersingers will not treat me fairly?"

"Stay, stay, Walther, not so fast! I want to say of yesterday's experience: the Mastersingers are, after all, men of honour. They were hard on thee yesterday, but thou hast troubled them much. Thy song was as strange, its kind as new to them as it was beautiful, and they have thought of it again and again since then. If they can make themselves familiar with such beauty they will not fail to give thee credit. I own I am much troubled and know not what to do for you."

"I wonder could it be possible that I have had an inspiration in my sleep that might lead me to win my dear Eva?" the knight said, taking heart.

"That we shall soon know. Sir Walther, stand thou there, and sing thy song, and I will sit here and write it down. So it shall not escape thee. Come, begin, Sir Knight," Sachs cried, becoming hopeful for the young man. Trembling with anxiety Walther took his stand and began his song, while Hans placed himself at the table to write it down.

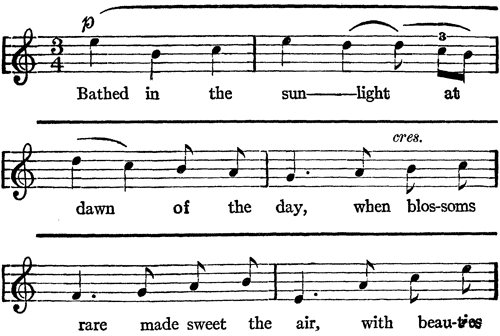

[Listen]

Bathed in the sunlight at dawn of the day,when blossoms raremade sweet the air,with beauties teeming,past all dreaming,a glorious garden lay, cheering my way.

As the knight sang he became more and more inspired and when he had finished Hans Sachs was wild with delight.

"It is true! – you have had a wonderful inspiration. Go now to your room, and there you will find clothing gay enough for this great occasion. No matter how it came there! – it is there! I have all along believed in you, and that you would sing, and I have provided for it." The knight went rejoicing to put on his new clothes.

Now Hans, when he went with Walther to his bedroom, had left the manuscript of the great song upon the table, and no sooner had he gone out than Beckmesser, looking through the window and finding the place empty, slipped in. He was limping from the effects of the fight and altogether cut a most ridiculous figure. He was very richly dressed, but that did not conceal his battered appearance. Every step he took he rubbed first his back and then his shins. He should have been in bed and covered with liniments. Suddenly he espied the song upon Hans's table. He believed that after all Hans was going to sing, and if he should, all would be up with himself. Wild with rage, Beckmesser picked up the song and stuffed it into his pocket. No sooner had he done so than the bedroom door opened, and Hans Sachs came out in gala dress, ready for the festival; seeing Beckmesser, he paused in surprise.

"What, you? Sir Marker? Surely those shoes of yours do not give you trouble so soon?"

"Trouble! The devil! Such shoes never were. They are so thin, I can feel the smallest cobblestone through them. No matter about the shoes, however – though I came to complain to you about them – for I have found another and far worse cause of complaint. I thought you were not to sing."

"Neither am I."

"What, you deny it – when I have just found you out!" Beckmesser cried in a foaming rage. Hans looked at the table and saw that the manuscript was gone. He grinned.

"So, you took the song, did you?" he asked.

"The ink was still wet."

"True, I'll be bound!"

"So then I've caught you deceiving!"

"Well, at least you never caught me stealing, and to save you from the charge I'll just give you that song," Hans replied, still smiling. Beckmesser stared at him.

"I'll warrant you have the song by heart," he said, narrowly eyeing the shoemaker.

"No, that I haven't. And further than that, I'll promise you not to lay any claim to it that shall thwart your use of it – if you really want it." Hans spoke carelessly, watching the greedy town clerk from the tail of his eye.

"You mean truly, that I may use that song as I like?"

"Sing it if you like – and know how," Sachs said obligingly.

"A song by Hans Sachs!" he exclaimed, unable to hide his joy – because no one in Nuremberg could possibly write a song like Sachs. "Well, well, this is very decent of you, Sachs! I can understand how anxious you are to make friends with me, after your bad treatment last night." Beckmesser spoke patronizingly, while his heart was fairly bursting with new hope. Any song by Hans Sachs would certainly win him the prize, even if he could but half sing it.

"If I am to oblige you by using this song," he hesitated, "then swear to me you will not undo me by laying claim to it." After all, he was feeling considerable anxiety about it. That he should be saved in this manner was quite miraculous.

"I'll give my oath never to claim it so long as I live," Sachs answered earnestly, thinking all the while what a rascal Beckmesser was. "But, friend Beckmesser, one word; I am no scoffer, but truly, knowing the song as I do, I have my doubts about your being able to learn it in an hour or so. The song is not easy."

"Have no fear, Hans Sachs. As a poet, your place is first, I know; but believe me, friend, when it comes to 'tone' and 'mode,' and the power to sing, I confess I have no fear – nor an equal," the conceited ass declared. "I tell you, confidentially, I have now no fear of that presumptuous fellow, Walther. With this song and my great genius, we shall no longer fear his bobbing upon the scene and doing harm." Assured of success at last, away went Beckmesser, limping and stumbling, to learn his song.

"Well, never did I see so malicious a fellow," Hans declared, as Beckmesser stumbled out of sight. "And there comes Evchen – hello, my Evchen, thou art dressed very fine. Well, well, it is to be thy wedding day, to be sure."

"Yes – but the shoe pinches," she said putting her little foot upon the bench.

"That will never do. That must be fixed," Hans answered gravely, his eyes twinkling. He fell to examining the shoes. "Why, my child, what is wrong with it? I find it a very fine fit?"

"Nay, it is too broad."

"Tut, tut, that is thy vanity. The shoe fits close, my dear."

"Well, then I think it is the toes that hurt – or maybe the heel, or maybe – " she looked all about, hoping to see Walther. At that moment he entered, and Eva cried out. Then Hans said:

"Ah, ah! Ho, ho! That is where the shoe pinches, eh? Well, be patient, that fault I shall mend very soon," he declared, thinking of the song that Beckmesser had stolen, while he took off the shoe and sat once more at his bench. Then he said slyly:

"Lately I heard a beauteous song. I would I might hear its third verse once more." Immediately, Walther, looking at Eva, began softly to sing the famous song. As it magically swelled, Sachs came to her and again fitted the shoes. When the song was rapturously finished, Eva burst into hysterical sobbing, and threw herself into the shoemaker's arms. But this scene was interrupted by the coming of Lena and David, all dressed for the fête.

"Come, just in time!" Sachs cried. "Now listen to what I have to say, children. In this room, a song has just been made by this knight, who duly sang it before me and before Eva. Now, do not forget this, I charge you; so let us be off to hear him christened a Mastersinger."

All then went out into the street except David, who lingered a moment to fasten up the house. All the way to the meadow where the fête was to be held were sounding trumpets and horns, glad shouts and laughter. Very soon the little group from Sachs's reached the fête, and there they found a gala sight.

Many guilds had arrived and were constantly arriving. Colours were planted upon the raised benches which each guild occupied by itself. A little stream ran through the meadow, and upon its waters boats were continually being rowed, full of laughing men and women, girls and boys. As each new guild disembarked, it planted its colours. Refreshment stands were all about, and apprentices and journeymen were having great sport.

The apprentices and girls began a fine dance, while the people kept landing at the dock and coming from their boats.

There came the bakers, the tailors, and the smiths; then the informal gaiety came to a sudden pause and the cry went up that the great Mastersingers themselves had arrived. They disembarked and formed a long procession, Kothner going ahead bearing the banner, which had the portrait of King David and his harp upon it.

At sight of the banner all waved their hats, while the Masters proceeded to their platform.

When they had reached their place, Pogner led Eva forward, and at the same moment Hans Sachs arrived and again all waved and cheered loudly. Eva took the place of honour, and behind them all was – Beckmesser, wildly struggling to learn his great song. He kept taking the manuscript from his pocket and putting it back, sweating and mumbling, standing first on one of his sore feet and then upon the other, a ridiculous figure, indeed.

At length, Sachs stood up and spoke to those who had welcomed him so graciously.

"Friends, since I am beloved of thee, I have one favour to ask. The prize this day is to be a unique one, and I ask that the contest be open. It is no more than fair, since so much is to be won. I ask that no one who shall ask for a chance to sing for this fair prize be denied. Shall this be so?"

While he waited for an answer, every one was in commotion.

"Say, Marker," he asked of Beckmesser, "is this not as it should be?"

That rascal was wiping his face from which the sweat was streaming and trying in despair to conquer the knight's song.

"You know you need not sing that song unless you wish," Hans reminded him, aside.

"My own is abandoned, and now it is too late for me to make another," Beckmesser moaned; "but with you out of the contest – well, I shall surely win with anything. You must not desert me now."

"Well, let it be agreed," Hans cried aloud, "that the contest shall be open to all; so now begin."

"The oldest first," Kothner cried, thus calling attention to the age of Beckmesser. "Begin, Beckmesser," another shouted.

"Oh, the devil," Beckmesser moaned, trying to peep again at the song which he had not been able to learn. He desperately ascended the mound which was reserved for the singers, escorted by an apprentice. He stumbled and nearly fell, so excited was he, and so frightened at his plight, for he did not know the song, and he had none of his own. Altogether he was in a bad way – but he was yet to be in a worse!

"Come and make this mound more firm," he snarled, nearly falling down. At that everybody laughed. Finally he placed himself, and all waited for him to begin. This is how he sang the words of the first stanza:

Bathing in sunlight at dawning of the day,With bosom bare,To greet the air;My beauty steaming,Faster dreaming,A garden roundelay wearied my way.Only compare this with the words of the song as Walther sang them! The music matched the words for absurdity.

"Good gracious! He's lost his senses," one Mastersinger said to another. Beckmesser, realizing that he was not getting the song right, became more and more confused. He felt the amazement of the people, and that made him desperate. At last, half crazed with rage and shame, he pulled the song from his pocket and peeped at it. Then he tried again, but turned giddy, and at last tottered down from the mound, while people began to jeer at him. Hans Sachs might have been sorry for the wretch, had he not known how dishonest he had been, willing to use another's song that he might gain the prize.

Beckmesser rushed furiously toward Sachs and shook his fist at him:

"Oh, ye accursed cobbler! Ye have ruined me," he screamed, and rushing madly away he lost himself in the crowd. In his rage, he had screamed that the song was Sachs's, but nobody would believe him, because, as Beckmesser had sung it, it had sounded so absurd.

Sachs took the manuscript quietly up, after Beckmesser had thrown it down.

"The song is not mine," he declared. "But I vow it is a most lovely song, and that it has been sung wrong. I have been accused of making this, and now I deny it. I beg of the one who wrote it to come forth now and sing it as it should be sung. It is the song of a great master, believe me, friends and Mastersingers. Poet, come forth, I pray you," he called, and then Walther stepped to the mound, modestly. Every one beheld him with pleasure. He was indeed a fine and gallant-looking fellow.

"Now, Masters, hold the song; and since I swear that I did not write it, but know the one who did – let my words be proved. Stand, Sir Knight, and prove my truth." Then Kothner took the manuscript that the Mastersingers might follow the singing and know if the knight was honest; and Walther, standing in the singers' place, began the song a little fearfully.