Полная версия

Windflower Wedding

ELIZABETH ELGIN

Windflower Wedding

Dedication

For my own ‘Clan’

Sally, Tim, Maria

Joanne, David, Angela

Rachel, Rhiannon

Jayne and Rebecca

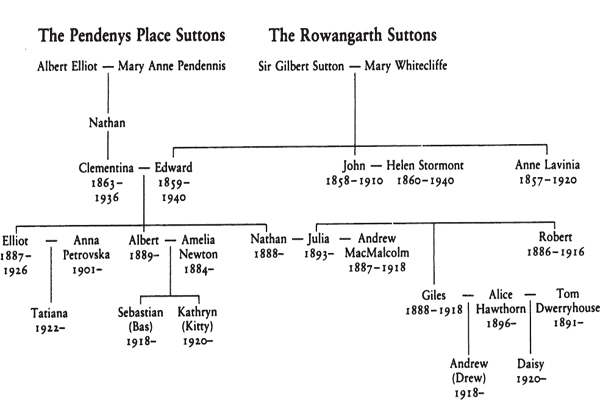

Family Tree

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Family Tree

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

About the Author

By the Same Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

1

1942

Home. Keth Purvis smiled with pure pleasure. Where he was being driven he had no idea, and cared still less, because this morning he had disembarked at Greenock. Not quite home. Holdenby in the North Riding of Yorkshire was home, but Scotland was near enough! Now he was only a telephone call away from Daisy; now, the Atlantic no longer separated them.

‘So do you want the good news first, or the bad?’ his superior in Washington had asked.

‘Whichever, sir.’

They had turned him down, he’d thought; turned down his request to return to England, but the bad news was that that request was approved – with conditions. The good news was that when he returned to England, when a passage could be arranged for him, he would be promoted to the rank of captain.

He wasn’t, he recalled, offered any details. It was a take-it-or-leave-it deal, with no questions asked and no answers given.

He had taken it; had grasped it eagerly, for what condition could be so demanding that Daisy was not worth it?

That had been on his birthday in July. Now it was September and the heather on the hills fading, the bracken turning to gold. Days of waiting became weeks, then months. His elation turned to dejection. They had forgotten him, he was sure of it, until one day he was on his way on a troopship filled with American soldiers and airmen and, though he only once glimpsed them, a score of nurses, carefully chaperoned.

They had not sailed in convoy. The Queen Mary was too fleet to be so confined. She sailed alone, keeping a zigzag course the whole way across the Atlantic to outwit submarine commanders who would give eyeteeth and more to sink her or her sister ship the Queen Elizabeth. The Mary and the Lizzie – and the Mary had borne him safely home. To Daisy.

‘Where are we?’ he asked of the woman driver.

‘Sir – I don’t rightly know …’

‘Somewhere in Scotland, surely?’

‘Yes, sir. Somewhere in Scotland.’ She stared ahead, her cheeks pinking.

‘So if you don’t know where we are,’ he teased, ‘how will you know when we get there?’

She could well be lost, he thought mischievously. It was two years since signposts had been removed – even the one at Holdenby crossroads – so that the enemy, when he parachuted in, should not know where he had landed. Then, Britain daily had expected invasion and though it was almost certain that invasion would never happen now, still the signposts and names of railway stations had not been put back.

‘Sir. I know approximately where I am.’ She glanced at him sideways and saw the smile on his face. ‘And I know exactly where we are going, but you know I can’t tell you!’

‘Of course, Sergeant.’ He didn’t care where they were going. He had always thought – when They had told him his request to return to England had been approved, but with conditions attached – that he would be sent to some out-of-the-way, hush-hush place. Another Bletchley, only in the wilds. Doing exactly the same thing he had done at Bletchley. And where more wild than this, with the road they travelled little wider than a cart track and getting narrower by the mile?

A beautiful wilderness, for all that. To their left, the head of a loch, circled with hills, and to their right, mile upon mile of pine trees and tangled undergrowth and the sun, big and orange, beginning to sink behind those purple hills.

He looked at his watch. Ten o’clock. Daylight lasted longer the further north they travelled. In London – and in Liverpool too – blackout conditions would already be in force, he supposed.

‘What time is blackout?’

‘Depending on where you are – and give or take a minute or two – round about ten o’clock.’

‘Should you have told me that, sergeant?’ he said with mock severity.

‘Oh yes, sir. I got it from the newspaper this morning.’

She was biting on her bottom lip to suppress a smile. She was really rather nice. Married, of course. Her wedding ring was the first thing he noticed about her capable left hand. There were many married women in the armed forces, he supposed, and soon, given luck and seven days’ marriage leave, Daisy would be another of them.

‘I don’t suppose,’ he hazarded, shifting his position the better to see her face, ‘that if we were to pass a phone box you could stop? I’d like to ring my fiancée. We haven’t spoken to each other for –’

‘Sir!’ She cut him short, her face all at once very serious. ‘There are no phone boxes around here. All removed. Security, see. But even if there were and you ordered me to stop – we-e-ll, I’d be bound to report it as soon as we arrived because it would be more than my stripes were worth if I didn’t!’

‘And you’ll report this conversation?’

‘No, sir.’ She was smiling again. ‘Not this time. Only you’ve got to realize the way it is.’

‘Yes. I realize.’ Phones, where they were going, would be listened-in to or scrambled, and every letter he wrote censored. He expected it and he didn’t care, ‘I suppose we are allowed to have phone calls?’

‘With permission, yes, sir. You’ll be able to phone out, sometimes, but there are no calls allowed in. I’ve been there a year now, and I still don’t know the phone number. And when you do phone, you’ll have to get used to the fact that someone will almost certainly be listening.’

‘Hmm.’ He folded his arms and stared ahead. More hush-hush than Bletchley Park, this new destination. At Bletchley he had at least been trusted with the phone.

Then he shifted in his seat, straightened his shoulders and allowed himself a small, secret smile. He was home and soon Daisy would know it in spite of all the petty restrictions.

And that was all that mattered!

Wren Daisy Dwerryhouse, summoned to the phone in the hall at Wrens’ Quarters, Hellas House, said, ‘Dwerryhouse,’ and waited, breath indrawn. It was always like this now, when anyone at all phoned.

Keth? whispered a voice inside her, even though she knew it would be Mam or Drew or Tatty.

‘Hi, Daiz!’ Only Drew called her Daiz. ‘Just thought I’d ring, see how you are and if there are any messages for Rowangarth.’

‘Drew! You’re going home!’

‘Only seventy-two hours. We’re getting de-gaussed again so most of us have got a spot of leave.’

‘Is Kitty going with you?’

‘She is. She managed to wangle it. Well – you know Kitty!’

Daisy knew her, and liked her; liked her a lot in spite of the fact that Kitty’s coming to England had resulted in near heartbreak for Lyndis, with whom Daisy shared a cabin.

‘Well, enjoy yourselves. I’m just fine, tell Mam and Dada. And give my love to Aunt Julia. I should be home on long leave myself before so very much longer. That’ll put a smile on Mam’s face. Oh – and give my love to Kitty too, won’t you?’

She smiled into the receiver as she replaced it; just as if she were smiling at Drew, her brother – her half-brother. Dear Drew who was so in love, just as she was, and planning a wedding as soon as They, the faceless ones, allowed it because in wartime, They could do anything they wanted and without so much as a by-your-leave.

She opened the door of Cabin 4A, closed it carefully, then paused to think about what she would say.

‘That was Drew on the phone.’ Leading-Wren Lyndis Carmichael said it for her. ‘And he’s in dock and taking Kitty out and not you and me.’ Not any more, since Kitty.

‘Yes, but they’re going home. He’s got seventy-two hours’ leave. He just phoned to see if there were any messages.’

‘I see. And you don’t have to look so guilty. I brought it on myself, didn’t I? Fell hook, line and sinker for him and then he ditches me for Kitty Sutton, one of your hallowed Clan!’

‘No, Lyn! Drew liked you a lot – then Kitty happened along and that was it! It was nothing to do with the Clan.’

‘You’re right. It wasn’t. And I should’ve got used to it by now, but being dropped still hurts, Daisy, because I still love him – more than ever, if that’s possible. Even though he’s going to marry Kitty, it doesn’t stop me wanting him.’

‘Lyn, love – what can I say? Both you and Drew are special to me, and Kitty too, so I’ve got to sit on the fence as far as you and he are concerned. Don’t ask me to take sides.’

‘I won’t. Only you can’t turn love off. You can try, but the loving is always there.’

‘I know. It would be the same for me if Keth found someone else. And don’t think I’m all smug, Lyn, because I’ve got a ring on my finger. I worry, sometimes, that we’ll be so long apart he’ll forget what I look like. I mean – why did he have to be sent back to Washington? Three years away, then one day, out of the blue, he’s on the phone – back home. And just when we think we’ll be getting married They send him away again. Who do They think They are, then? Almighty God?’

‘Of course they do! Has it taken you all this time for the penny to drop? We are only names and numbers to that lot! But I’ll tell you something, Dwerryhouse D. I’m going to have the time of my life cocking a snook at Authority the minute I get back to civvy street again. Just imagine seeing an officer and saying, “Hullo, mate,” to him instead of saluting! Or maybe even winking!’

‘“When I get back to civvy street again.” How many millions of times must that have been said, Lyn?’

‘Lord knows, and He won’t tell! Anyway, now that we’ve done our stint for King and Country for the day …’

‘And eaten a mediocre, kept-warm lunch.’

‘Very mediocre. So what say we take a walk in the park? There won’t be many more lovely afternoons left. We’re well into September, now.’

‘Mm. Had you realized that we’re three weeks into year four of the war?’

‘I had. But if it hadn’t been for the war, I wouldn’t have met Drew, had you thought?’

‘Drew is taboo!’

‘Okay. And worrying about Keth in Washington?’

‘That too.’

‘So what shall we talk about? Shortage of lipsticks and face cream?’

‘Or the blackout?’

‘And the pubs always running out of beer and never a bottle of gin to be seen!’

‘And my wedding dress, hanging at Rowangarth!’

‘Now we’re back to Keth again!’

They began to laugh, because it was best you laughed about things you were powerless to change, then pulled on hats and gloves and made for the park, just across the road.

Navy-blue woolly gloves and thick black stockings on a beautiful Indian summer day in September, Lyn thought. Yuk!

‘By the way,’ she said, when they had fallen into step and were making towards the Palm House, ‘I know it’s taboo, but what did you say they were doing to Drew?’

‘Not Drew – his ship! And surely you know what degaussing is?’

‘I don’t – except the entire ship’s company gets a seventy-two-hour leave pass when it happens.’

‘De-gaussing is passing an electric current through the copper wire that’s fixed round the ship. It neutralizes it, sort of, so that mines won’t go off when they sail over one.’

‘Clever stuff – especially if you happen to be on a minesweeper like Drew is. Does it really work?’

‘It has done, this far.’ Daisy crossed her fingers. ‘I suppose they’re having a top-up, or something. So what shall we talk about?’ Daisy said very firmly.

‘Heaven knows!’ What was there to talk about that didn’t lead back eventually to Keth or Drew? Lyn brooded. Or more to the point, how Drew Sutton was crazily in love with Kitty, his cousin from Kentucky and had proposed to her and spent the night with her within the space of twenty-four hours? ‘I suppose we could talk about what we would do with a hundred clothing coupons; if we were allowed clothing coupons, that is.’

‘I’d rather talk about pay parade tomorrow,’ Daisy said. After all, pay parade every two weeks was just about the only thing you could be sure about!

Unspeaking, they walked past the shattered Palm House and on towards the ornamental lake. Life got tedious, sometimes, for those serving in His Majesty’s Forces, and often – much, much too often – very lonely.

Alice Dwerryhouse was well pleased. She had been to a salvage sale and come away with enough flower-printed cotton to make two dresses – one for Daisy and one for herself. And after thinking long and hard she bought five yards of pale blue fine woollen material, smoke-stained and in parts water-marked too. She had worried about the pale blue wool, washing it carefully, thinking she had been a fool to waste good money on something that could shrink into nothing as well as wasting precious soap flakes.

She need not have worried. It had blown dry on the line and come up fluffy and soft – and stain-free and pre-shrunk, into the bargain. Now Daisy could have a nice going-away costume and the beauty of salvage sales was that material sold there came not only cheaply but without the need to hand over clothing coupons for it! You paid your money and you took pot luck, she supposed. And it wasn’t very nice, if you let yourself dwell on it overmuch, that such windfalls were the result of some fabric warehouse being bombed and the bolts of wool and cotton knocked down for salvage.

She pulled the iron carefully over the pale blue length, trying hard not to gloat that now Daisy would not only have a proper white wedding dress but a going-away outfit too. Indeed, she sighed, coming down to earth with a jolt, all her daughter lacked now was a bridegroom and Keth Purvis was miles away in Washington.

It was all Hitler’s fault, though. Evil Hitler who was the cause of it all, and why the air force lads didn’t bomb him to smithereens she didn’t know. Or maybe, she thought, smiling wickedly, how would it be if the good Lord worked a crafty one so that Hitler and half a dozen mothers of sons and daughters away in the forces could be locked in a room for ten minutes. Ten minutes, that’s all it would take!

‘Alice! You were miles away. Penny for them!’ Julia Sutton closed the kitchen door behind her – Julia never knocked – then sat down beside the fire.

‘A penny? No, they’re worth much more than that!’ They were too, considering what she had just done to Hitler. ‘But there’s good news written all over your face – so tell me.’

‘Good news indeed! Were you going to put the kettle on?’

‘You do it. Just want to finish pressing this material. It’s come up real well, though I can’t say I didn’t have second thoughts after I bought it. But what’s happened?’

‘Drew and Kitty, that’s what.’ Julia set the kettle to boil. ‘Kitty phoned. Can I put up with the pair of them for three days, she said. Drew’s been given leave!’

‘Leave? A bit sudden, isn’t it? He’s not –’

‘Not going overseas? No, I don’t think so. Something that had to be done to the ship, she said. Very vague. You know what Kitty’s like. She didn’t even get round to saying what time before the pips went, but I take it they’ll be arriving on the six-thirty into Holdenby – if not before, of course, if they hitch a lift from York.’

‘And you’re still pleased – about them getting married, I mean?’

‘Delighted. Kitty is so adorable – she always was, come to think of it. Quite the naughtiest of the Clan, but such a way with her. You like her, don’t you, Alice?’

‘You know I do. I always did. We’re very lucky, you and me both.’ Carefully she draped the precious material to air, then folded the ironing blanket carefully. ‘And I’ve got news for you too. Daisy’s leave has been approved. She’ll be home a week from now. And I’m not supposed to tell you, so you’ll have to be very surprised when you see him in uniform. Tom’s been made a sergeant. There’ll be no living with him now!’ Alice smiled fondly. Tom – a marksman in the Great War; now a sergeant in the Home Guard. Funny how being married to him got better with each year. Different, but better. Two more years would see their silver wedding anniversary. Mind, she sighed, if the war hadn’t happened she could well have been a grandmother now.

‘Why the sigh?’

‘Oh, just thinking about Keth and Daisy being apart. I ought to be glad he’s where he is and not in the thick of the fighting, but I would, just once, like to see the six of them together again, just like they used to be when they were growing up.’

‘My Clan? Drew, Daisy, Keth, Bas, Kitty and Tatty. And five of them are in England now. Only Keth to will and wish home, then I shall take their photo again, just as I did in the Christmas of ’thirty-six. ’Thirty-seven, remember, was the last summer they were all together. And I’m sure they’ll be together again one day.’

‘When the war is over, happen?’

‘No, Alice. Long before then. I know it!’

‘Then fingers crossed that you’ll be right.’

‘I am.’ Julia stirred her tea thoughtfully. ‘Did you see it in the paper, by the way, that the milk ration is being cut?’

‘I did. It’s down to five pints a week now, between the two of us!’

‘We-e-ll, I suppose Home Farm will slip us the odd pint, now and again. It isn’t as though milk has to be brought here by sea. I don’t feel so bad about getting extra milk – not like sugar, or tea or petrol. Wouldn’t touch those. Wouldn’t risk a seaman’s life.’

‘I should think not, and us with a sailor son!’ Alice drained her cup, then upended it into her saucer, gazing at the tea leaves clinging to the sides. ‘Wish Jinny Dobb were here to read our cups. Jin wasn’t often wrong, was she?’

‘No. Dear Jin. It’ll be a year on the fifth of October since they were all killed – and a year on the tenth since Mother died.’

‘I know.’ Alice reached out for Julia’s hand. ‘I loved her too, don’t forget – I loved all of them. But they wouldn’t want us to fret. None of them would.’

‘Mm. And we’ve still got each other, you and me. Sisters to the end?’

‘Sisters,’ Alice said, gravely and gratefully, ‘to the end …’

‘Have you ever stopped to think, Gracie Fielding, that if this dratted old war goes on much longer you’ll be a time-served gardener?’ Jack Catchpole, sitting on his upended apple box, blew on his tea. ‘That is, of course, provided you don’t go getting any ideas about getting wed and wasting all the knowledge I’ve passed on to you!’

‘Married, Mr Catchpole?’ Gracie blushed hotly. ‘Now whatever gave you an idea like that?’

‘Gave me? When it’s sticking out a mile and that young Sebastian never away? Don’t know how he manages to get so much leave!’

‘Well, he won’t be able to get away so often in future. It was quite easy, once, but now the aerodrome – er – airfield, is ready, Bas says the bombers will start arriving soon and things will be different.’ A whole new ball game, he said it would be.

‘Ar. I did hear as how the Americans down south are already going bombing, and serve those Nazis right, an’ all! But young Bas won’t be flying bombers, will he?’

‘No. He wanted to, but his hands – well, his left hand in particular, put paid to that.’ She added a silent thank goodness.

‘Never mind. His hands didn’t stop him getting to be a vet’nary with letters after his name, so they can’t be all that bad. And it was a miracle he wasn’t taken in that fire like Mrs Clementina was.’

‘I never notice his hands, truth known,’ Gracie smiled.

‘Of course you don’t. Just a few old scars. Mind, I shall want to know good and early when you and him set a date. I shall take it amiss if you don’t let me do the flowers and buttonholes for you. And think on! We want no winter weddings when there’s only chrysanths to make bouquets of. See that you plan it for the summer when there’s flowers about.’

‘Mr Catchpole!’ Gracie jumped to her feet. ‘I’ve told you time and time again that I don’t think it’s at all wise to get overfond of anyone in wartime. You could get hurt. Look what happened to Tatty.’

‘Aye, poor little wench. But wisdom has a habit of popping out of the window, Gracie lass, when love walks in at the door, and don’t you forget it.’

‘I won’t. I’m not likely to. I’ve told you that often enough!’

‘Aye, but it seems no one has told young Bas. He’s a grand lad, you can’t but admit it.’

‘Yes, and he can get pipe tobacco in their canteen and he brings you some every time he comes. You encourage him!’ Gracie said hotly. ‘But you’ve no need to worry about losing me. I want to do my apprenticeship. I want to be a lady gardener when the war is over. I don’t want ever to go back into an office so you’d better accept that you’re stuck with me, ’cos I’m not going to marry Bas Sutton.’

‘Now is that a fact?’ Jack Catchpole slurped noisily on his tea. ‘Well, you could’ve fooled me, Gracie Fielding,’ he chuckled throatily. Oh, my word, yes!

2

The army car, camouflaged in khaki and green and black, turned sharp left and the driver stopped at a guard post where a hefty red and white gate barred their way.

‘Hi,’ the driver said laconically, offering her identity pass, even though she obviously knew and was known by the soldiers who stood guard. ‘One passenger, male.’ She turned to Keth. ‘Your ID sir, please.’

Keth fished in his pocket, offering his pass. The corporal of the guard switched on his flashlight, studying it in great detail. He handed it back, then shone the light full in Keth’s face. ‘Carry on, driver!’ he rasped, satisfied with the likeness.

Saluting smartly he motioned an armed guard to open the gate, winked at the driver, who winked back, then waved them forward.

‘Very officious,’ Keth remarked mildly, blinking rapidly as black spots caused by the torch glare danced in front of his eyes.

‘Just a couple more miles – and another checkpoint,’ the sergeant smiled. ‘Have your ID ready.’

The black spots were fading and Keth looked around him. The sun had sunk behind the hills, and in the half-light a crescent moon hung silver white at the end of a long avenue of tall pines.