полная версия

полная версияVoyage of the Paper Canoe

Finding that the wind usually rose and fell with the sun, we now made it a rule to anchor our boat during most of the day and pull against the current at night. The moon and the bright auroral lights made this task an agreeable one. Then, too, we had Coggia's comet speeding through the northern heavens, awakening many an odd conjecture in the mind of my old salt.

In this high latitude day dawned before three o'clock, and the twilight lingered so long that we could read the fine print of a newspaper without effort at a quarter to nine o'clock p. m. The lofty shores that surrounded us at Quebec gradually decreased in elevation, and the tides affected the river less and less as we approached Three Rivers, where they seemed to cease altogether. We reached the great lumber station of Three Rivers, which is located on the left bank of the St. Lawrence, on Friday evening, and moved our canoe into quiet waters near the entrance of Lake of St. Peter. Rain squalls kept us close under our hatch-cloth till eleven o'clock a. m. on Saturday, when, the wind being fair, we determined to make an attempt to reach Sorel, which would afford us a pleasant camping-ground for Sunday.

Lake of St. Peter is a shoal sheet of water twenty-two miles long and nearly eight miles wide, a bad place to cross in a small boat in windy weather. We set our sail and sped merrily on, but the tempest pressed us sorely, compelling us to take in our sail and scud under bare poles until one o'clock, when we double-reefed and set the sail. We now flew over the short and swashy seas as blast after blast struck our little craft. At three o'clock the wind slackened, permitting us to shake out our reefs and crowd on all sail. A labyrinth of islands closed the lake at its western end, and we looked with anxiety to find among them an opening through which we might pass into the river St. Lawrence again. At five o'clock the wind veered to the north, with squalls increasing in intensity. We steered for a low, grassy island, which seemed to separate us from the river. The wind was not free enough to permit us to weather it, so we decided to beach the boat and escape the furious tempest. But when we struck the marshy island we kept moving on through the rushes that covered it, and fairly sailed over its submerged soil into the broad water on the other side. Bodfish earnestly advised the propriety of anchoring here for the night, saying, "It is too rough to go on;" but the temptation held out by the proximity to Sorel determined me to take the risk and drive on. Again we bounded out upon rough water, with the screeching tempest upon us. David took the tiller, while I sat upon the weather-rail to steady the boat. The Mayeta was now to be put to a severe test; she was to cross seas that could easily trip a boat of her size; but the wooden canoe was worthy of her builder, and flew like an affrighted bird over the foaming waves across the broad water, to the shelter of a wooded, half submerged island, out of which rose, on piles, a little light-house. Under this lee we crept along in safety. The sail was furled, never to be used in storm again. The wind went down with the sinking sun, and a delightful calm favored us for our row up the narrowing river, eight miles to the place of destination.

Soon after nine o'clock we came upon the Acadian town, Sorel, with its bright lights cheerily flashing out upon us as we rowed past its river front. The prow of our canoe was now pointed southward toward the goal of our ambition, the great Mexican Gulf; and we were about to ascend that historic stream, the lovely Richelieu, upon whose gentle current, two hundred and sixty-six years before, Champlain had ascended to the noble lake which bears his name, and up which the missionary Jogues had been carried an unwilling captive to bondage and to torture.

We ascended the Richelieu, threading our way among steam-tugs, canal-boats, and rafts, to a fringe of rushes growing out of a shallow flat on the left bank of the river, just above the town. There, firmly staking the Mayeta upon her soft bed of mud, secure from danger, we enjoyed a peaceful rest through the calm night which followed; and thus ended the rough passage of one week's duration – from Quebec to Sorel.

CHAPTER III

FROM THE ST. LAWRENCE RIVER TO TICONDEROGA, LAKE CHAMPLAIN

THE RICHELIEU RIVER. – ACADIAN SCENES. – ST. OURS. – ST. ANTOINE. – ST. MARKS. – BELŒIL. – CHAMBLY CANAL. – ST. JOHNS. – LAKE CHAMPLAIN. – THE GREAT SHIP-CANAL. – DAVID BODFISH'S CAMP. – THE ADIRONDACK SURVEY. – A CANVAS BOAT. – DIMENSIONS OF LAKE CHAMPLAIN. – PORT KENT. – AUSABLE CHASM. – ARRIVAL AT TICONDEROGA.

QUEBEC was founded by Champlain, July 3, 1680. During his first warlike expedition into the land of the Iroquois the following year, escorted by Algonquin and Montagnais Indian allies, he ascended a river to which was afterwards given the name of Cardinal Richelieu, prime minister of Louis XIII. of France. This stream, which is about eighty miles long, connects the lake (which Champlain discovered and named after himself) with the St. Lawrence River at a point one hundred and forty miles above Quebec, and forty miles below Montreal. The waters of lakes George and Champlain flow northward, through the Richelieu River into the St. Lawrence. The former stream flows through a cultivated country, and upon its banks, after leaving Sorel, are situate the little towns of St. Ours, St. Rock, St. Denis, St. Antoine, St. Marks, Belœil, Chambly, and St. Johns. Small steamers, tug-boats, and rafts pass from the St. Lawrence to Lake Champlain (which lies almost wholly within the United States), following the Richelieu to Chambly, where it is necessary, to avoid rapids and shoals, to take the canal that follows the river's bank twelve miles to St. Johns, where the Canadian custom-house is located. Sorel is called William Henry by the Anglo-Saxon Canadians. The paper published in this town of seven thousand inhabitants is La Gazette de Sorel. The river which flows past the town is called, without authority, by some geographers, Sorel River, and by others St. Johns, because the town nearest its source is St. Johns, and another town at its mouth is Sorel. There are about one hundred English-speaking families in Sorel. The American Waterhouse Machinery supplies the town with water pumped from the river at a cost of one ton of coal per day. At ten o'clock on Monday morning we resumed our journey up the Richelieu, the current of which was nothing compared with that of the great river we had left. The average width of the stream was about a quarter of a mile, and the grassy shores were made picturesque by groves of trees and quaintly constructed farm-houses.

It was a rich, pastoral land, abounding in fine herds of cattle. The country reminded me of the Acadian region of Grand Pré, which I had visited during the earlier part of the season. Here, as there, were delightful pastoral scenes and rich verdure; but here we still had the Acadian peasants, while in the land of beautiful Evangeline no longer were they to be found. The New Englander now holds the titles to those deserted old farms of the scattered colonists. Our rowing was frequently interrupted by heavy showers, which drove us under our hatch-cloth for protection. The same large, two-steepled stone churches, with their unpainted tin roofs glistening like silver in the sunlight, marked out here, as on the high banks of the St. Lawrence River, the site of a village.

Twelve miles of rowing brought us to St. Ours, where we rested for the night, after wandering through its shaded and quaint streets. The village boys and girls came down to see us off the next morning, waving their kerchiefs, and shouting "Bon voyage!" Two miles above the town we encountered a dam three feet high, which deepened the water on a shoal above it. We passed through a single lock in company with rafts of pine logs which were on the way to New York, to be used for spars. A lockage fee of twenty-five cents for our boat the lock-master told us would be collected at Chambly Basin. It was a pull of nearly six miles to St. Denis, where the same scene of comfort and plenty prevailed. Women were washing clothes in large iron pots at the river's edge, and the hum of the spinning-wheels issued from the doorways of the farm-houses. Beehives in the well-stocked gardens were filled with honey, and the straw-thatched barns had their doors thrown wide open, as though waiting to receive the harvest. At intervals along the highway, over the grassy hills, tall, white wooden crosses were erected; for this people, like the Acadians of old, are very religious. Down the current floated "pin-flats," a curious scow-like boat, which carries a square sail, and makes good time only when running before the wind. St. Antoine and St. Marks were passed, and the isolated peak of St. Hilaire loomed up grandly twelve hundred feet on the right bank of the Richelieu, opposite the town of Belœil. One mile above Belœil the Grand Trunk Railroad crosses the stream, and here we passed the night. Strong winds and rain squalls interrupted our progress. At Chambly Basin we tarried until the evening of July 16, before entering the canal. Chambly is a watering-place for Montreal people, who come here to enjoy the fishing, which is said to be fair.

We had ascended one water-step at St. Ours. Here we had eight steps to ascend within the distance of one mile. By means of eight locks, each one hundred and ten feet long by twenty-two wide, the Mayeta was lifted seventy-five feet and one inch in height to the upper level of the canal. The lock-masters were courteous, and wished us the usual "bon voyage!" This canal was built thirty-four years prior to my visit. By ten o'clock p. m. we had passed the last lock, and went into camp in a depression in the bank of the canal. The journey was resumed at half past three o'clock the following morning, and the row of twelve miles to St. Johns was a delightful one. The last lock (the only one at St. Johns) was passed, and we had a full clearance at the Dominion custom-house before noon.

We were again on the Richelieu, with about twenty-three miles between us and the boundary line of the United States and Canada, and with very little current to impede us. As dusk approached we passed a dismantled old fort, situated upon an island called Ile aux Noix, and entered a region inhabited by the large bull-frog, where we camped for the night, amid the dolorous voices of these choristers. On Saturday, the 18th, at an early hour, we were pulling for the United States, which was about six miles from our camping-ground. The Richelieu widened, and we entered Lake Champlain, passing Fort Montgomery, which is about one thousand feet south of the boundary line. Champlain has a width of three fourths of a mile at Fort Montgomery, and at Rouse's Point expands to two miles and three quarters. The erection of the fort was commenced soon after 1812, but in 1818 the work was suspended, as some one discovered that the site was in Canada, and the cognomen of Fort Blunder was applied. In the Webster treaty of 1842, England ceded the ground to the United States, and Fort Montgomery was finished at a cost of over half a million of dollars.

At Rouse's Point, which lies on the west shore of Lake Champlain about one and one-half miles south of its confluence with the Richelieu, the Mayeta was inspected by the United States custom-house officer, and nothing contraband being discovered, the little craft was permitted to continue her voyage.

At the northern end of the harbor of Rouse's Point is the terminus of the Ogdensburg and the Champlain and St. Lawrence railroads. The Vermont Central Railroad connects with the above by means of a bridge twenty-two hundred feet in length, which crosses the lake. Before proceeding further it may interest the reader of practical mind to know that a very important movement is on foot to facilitate the navigation of vessels between the great Lakes, St. Lawrence River, and Champlain, by the construction of a ship-canal. The Caughnawaga Ship Canal Company, "incorporated by special act of the Dominion of Parliament of Canada, 12th May, 1870," (capital, three million dollars; shares, one hundred dollars each,) with a board of directors composed of citizens of the United States and Canada, has issued its prospectus, from which I extract the following:

"The commissioners of public works, in their report of 1859, approved by government, finally settled the question of route, by declaring that, 'after a patient and mature consideration of all the surveys and reports, we are of opinion that the line following the Chambly Canal and then crossing to Lake St. Louis near Caughnawaga, is that which combines and affords in the greatest degree all the advantages contemplated by this improvement, and which has been approved by Messrs. Mills, Swift, and Gamble.'

"The company's Act of Incorporation is in every respect complete and comprehensive in its details. It empowers the company to survey, to take, appropriate, have and hold, to and for the use of them and their successors, the line and boundaries of a canal between the St. Lawrence and Lake Champlain, to build and erect the same, to select such sites as may be necessary for basins and docks, as may be considered expedient by the directors, and to purchase and dispose of same, with any water-power, as may be deemed best by the directors for the use and profit of the company.

"It also empowers the company to cause their canal to enter into the Chambly Canal, and to widen, deepen, and enlarge the same, not less in size than the present St. Lawrence canals; also the company may take, hold, and use any portion of the Chambly Canal, and the works therewith connected, and all the tolls, receipts, and revenues thereof, upon terms to be settled and agreed upon between the company and the governor in council.

"The cost of the canal, with locks of three hundred feet by forty-five, and with ten feet six inches the mitre-sill, is now estimated at two million five hundred thousand dollars, and the time for its construction may not exceed two years after breaking ground.

"Probably no question is of more vital importance to Canada and the western and eastern United States than the subject of transportation. The increasing commerce of the Great West, the rapidity with which the population has of late flowed into that vast tract of country to the west and northwest of lakes Erie, Michigan, Huron, and Superior, have served to convince all well-informed commercial men that the means of transit between that country and the seaboard are far too limited even for the present necessities of trade; hence it becomes a question of universal interest how the products of the field, the mine, and the forest can be most cheaply forwarded to the consumer. Near the geographical centre of North America is a vast plateau two thousand feet above the level of the sea, drained by the Mississippi to the south, by the St. Lawrence to the east, and by the Saskatchewan and McKenzie to the north. This vast territory would have been valueless but for the water lines which afford cheap transport between it and the great markets of the world.

"Canada has improved the St. Lawrence by canals round the rapids of the St. Lawrence, and by the Welland Canal, connecting lakes Erie and Ontario, twenty-eight miles in length with a fall of two hundred and sixty feet, capable of passing vessels of four hundred tons. The St. Lawrence, from the east end of Lake Ontario, has a fall of two hundred and twenty feet, overcome by seven short canals of an aggregate length of forty-seven miles, capable of passing vessels of six hundred and fifty tons. The Richelieu River is connected with Lake Champlain by a canal of twelve miles from Chambly. A canal of one mile in length, at the outlet of Lake Superior, connects that lake with Lake Huron, and has two locks, which will pass vessels of two thousand tons. New York has built a canal from Buffalo, on Lake Erie, and from Oswego, on Lake Ontario, to Albany, on the Hudson River, of three hundred and sixty and of two hundred and nine miles, capable of passing boats of two hundred and ten tons; and she has also constructed a canal from the Hudson River into Lake Champlain of sixty-five miles, which can pass boats of eighty tons.

"Such is the nature of the navigation between tide-water on the Hudson and St. Lawrence and the upper lakes. The magnitude of the commerce of the Northwest has compelled the enlargement of the Erie and Oswego canals from boats of seventy-eight to two hundred and ten tons, while the St. Lawrence and Welland canals have also been enlarged since their first construction. A further enlargement of the Erie and Champlain canals is now strongly urged in consequence of the want of the necessary facilities of transport for the ever increasing western trade. The object of the Caughnawaga Ship-canal is to connect Lake Champlain with the St. Lawrence by the least possible distance, and with the smallest amount of lockage. When built, it will enable the vessel or propeller to sail from the head of lakes Superior or Michigan without breaking bulk, and will enable such vessels to land and receive cargo at Burlington and Whitehall, from whence western freights can be carried to and from Boston, and throughout New England, by railway cheaper than by any other route.

"It will possess the advantage, when the Welland Canal is enlarged and the locks of the St. Lawrence Canal lengthened, of passing vessels of eight hundred and fifty tons' burden, and with that size of vessel (impossible on any other route) of improved model, with facilities for loading and discharging cargoes at both ends of the route, in the length of the voyage without transshipment, in having the least distance between any of the lake ports and a seaport, and in having the shortest length of taxed canal navigation. The construction of the Caughnawaga Canal, when carried out, will remedy the difficulties which now exist and stand in the way of an uninterrupted water communication between the western states and the Atlantic seaboard."

From Rouse's Point we proceeded to a picturesque point which jutted into the lake below Chazy Landing, and was sheltered by a grove of trees into which we hauled the Mayeta. Bodfish's woodcraft enabled him to construct a wigwam out of rails and rubber blankets, where we quietly resided until Monday morning. The owner of the point, Mr. Trombly, invited us to dinner on Sunday, and exhibited samples of a ton of maple sugar which he had made from the sap of one thousand trees.

On Monday, July 20th, we rowed southward. Our route now skirted the western shore of Lake Champlain, which is the eastern boundary of the great Adirondack wilderness. Several of the tributaries of the lake take their rise in this region, which is being more and more visited by the hunter, the fisherman, the artist, and the tourist, as its natural attractions are becoming known to the public. The geodetical survey of the northern wilderness of New York state, known as the Adirondack country, under the efficient and energetic labors of Mr. Verplanck Colvin, will cover an area of nearly five thousand square miles. In his report of the great work he eloquently says:

"The Adirondack wilderness may be considered the wonder and the glory of New York. It is a vast natural park, one immense and silent forest, curiously and beautifully broken by the gleaming waters of a myriad of lakes, between which rugged mountain-ranges rise as a sea of granite billows. At the northeast the mountains culminate within an area of some hundreds of square miles; and here savage, treeless peaks, towering above the timber line, crowd one another, and, standing gloomily shoulder to shoulder, rear their rocky crests amid the frosty clouds. The wild beasts may look forth from the ledges on the mountain-sides over unbroken woodlands stretching beyond the reach of sight – beyond the blue, hazy ridges at the horizon. The voyager by the canoe beholds lakes in which these mountains and wild forests are reflected like inverted reality; now wondrous in their dark grandeur and solemnity, now glorious in resplendent autumn color of pearly beauty. Here – thrilling sound to huntsman – echoes the wild melody of the hound, awakening the solitude with deep-mouthed bay as he pursues the swift career of deer. The quavering note of the loon on the lake, the mournful hoot of the owl at night, with rarer forest voices, have also to the lover of nature their peculiar charm, and form the wild language of this forest.

"It is this region of lakes and mountains – whose mountain core is well shown by the illustration, 'the heart of the Adirondacks' – that our citizens desire to reserve forever as a public forest park, not only as a resort of rest for themselves and for posterity, but for weighty reasons of political economy. For reservoirs of water for the canals and rivers; for the amelioration of spring floods by the preservation of the forests sheltering the deep winter snows; for the salvation of the timber, – our only cheap source of lumber supply should the Canadian and western markets be ruined by fires, or otherwise lost to us, – its preservation as a state forest is urgently demanded. To the number of those chilly peaks amid which our principal rivers take their rise, I have added by measurement a dozen or more over four thousand feet in height, which were before either nameless, or only vaguely known by the names given them by hunters and trappers.

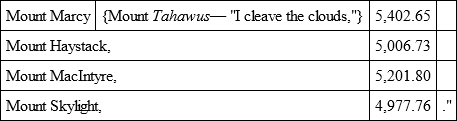

"It is well to note that the final hypsometrical computations fully affirm my discovery that in Mount Haystack we have another mountain of five thousand feet altitude. It may not be uninteresting also to remark that the difference between the altitudes of Mount Marcy and Mount Washington of the White Mountains of New Hampshire is found to be quite eight hundred feet. Mount Marcy, Mount MacIntyre, and Mount Haystack are to be remembered as the three royal summits of the state.

"The four prominent peaks are —

If the general reader will pardon a seeming digression to gratify the curiosity of some of my boating friends, I will give from the report of the Adirondack Survey Mr. Colvin's account of his singular boat, – one of the lightest yet constructed, and weighing only as much as a hunter's double-barrelled gun.

Mr. Colvin says:

"I also had constructed a canvas boat, of my own invention, for use in the interior of the wilderness on such of the mountain lakes as were inaccessible to boats, and which it would be necessary to map. This boat was peculiar; no more frame being needed than could be readily cut in thirty minutes in the first thicket. It was twelve feet long, with thin sheet brass prows, riveted on, and so fitted as to receive the keelson, prow pieces, and ribs (of boughs), when required; the canoe being made water-proof with pure rubber gum, dissolved in naphtha, rubbed into it."

Page 43 of Mr. Colvin's report informs the reader how well this novel craft served the purpose for which it was built.

"September 12 was devoted to levelling and topographical work at Ampersand Pond, a solitary lake locked in by mountains, and seldom visited. There was no boat upon its surface, and in order to complete the hydrographical work we had now, of necessity, to try my portable canvas boat, which had hitherto done service as bed or tent. Cutting green rods for ribs, we unrolled the boat and tied them in, lashing poles for gunwales at the sides, and in a short time our canvas canoe, buoyant as a cork, was floating on the water. The guides, who had been unable to believe that the flimsy bag they carried could be used as a boat, were in ecstasies. Rude but efficient paddles were hastily hewn from the nearest tree, and soon we were all gliding in our ten-pound boat over the waves of Ampersand, which glittered in the morning sunlight. To the guides the boat was something astonishing; they could not refrain from laughter to find that they were really afloat in it, and pointed with surprise at the waves, which could be seen through the boat, rippling against its sides. With the aid of the boat, with prismatic compass and sextant, I was able to secure an excellent map of the lake; and we almost succeeded in catching a deer, which was driven into the lake by a strange hound. The dog lost the trail at the water, and desiring to put him on the track, we paddled to him. He scrambled into the boat with an air of satisfaction, as if he had always travelled in just such a thing. Soon we had regained the trail, and making the mountains echo to his voice, he again pursued the deer on into the trackless forest.