полная версия

полная версияThe Mirror of Taste, and Dramatic Censor

Of the few who lived to see him and Garrick, the far greater number gave him the palm, with the exception of Garrick’s excellence in low comedy. Indeed he seems to have combined in himself the various powers of the three greatest modern actors, of Garrick, except as before excepted, of Barry, and of Mossop; add to which, he played Falstaff as well as Quin. The present writer got this from old Macklin, who was stored with anecdotes of his predecessors.

Of Betterton, Colley Cibber speaks thus, in his apology for his own life:

“Betterton was an actor, as Shakspeare was an author, both without competitors! formed for the mutual assistance, and illustration of each other’s genius! how Shakspeare wrote, all men who have a taste for nature may read, and know – but with what higher rapture would he still be read, could they conceive how Betterton played him! Then might they know, the one was born alone to speak what the other only knew to write! pity it is, that the momentary beauties flowing from a harmonious elocution, cannot, like those of poetry, be their own record! that the animated graces of the player can live no longer than the instant breath and motion that presents them; or at best can but faintly glimmer through the memory, or imperfect attestation of a few surviving spectators. Could how Betterton spoke be as easily known as what he spoke, then might you see the Muse of Shakspeare in her triumph, with all her beauties in their best array, rising into real life, and charming her beholders. But alas! since all this is so far out of the reach of description, how shall I show you Betterton? Should I therefore tell you, that all the Othellos, Hamlets, Hotspurs, Mackbeths, and Brutuses, whom you may have seen since his time, have fallen far short of him; this still would give you no idea of his particular excellence. Let us see then what a particular comparison may do! whether that may yet draw him nearer to you?

“You have seen a Hamlet perhaps, who, on the first appearance of his father’s spirit, has thrown himself into all the straining vociferation requisite to express rage and fury, and the house has thundered with applause; though the misguided actor was all the while (as Shakspeare terms it) tearing a passion into rags – I am the more bold to offer you this particular instance, because the late Mr. Addison, while I sate by him, to see this scene acted, made the same observation, asking me with some surprize, if I thought Hamlet should be in so violent a passion with the ghost, which though it might have astonished, it had not provoked him? for you may observe that in this beautiful speech, the passion never rises beyond an almost breathless astonishment, or an impatience, limited by filial reverence, to inquire into the suspected wrongs that may have raised him from his peaceful tomb! and a desire to know what a spirit so seemingly distressed, might wish or enjoin a sorrowful son to execute towards his future quiet in the grave! this was the light into which Betterton threw this scene; which he opened with a pause of mute amazement! then rising slowly, to a solemn, trembling voice, he made the ghost equally terrible to the spectator, as to himself! and in the descriptive part of the natural emotions which the ghastly vision gave him, the boldness of his expostulation was still governed by decency, manly, but not braving; his voice never rising into that seeming outrage, or wild defiance of what he naturally revered. But alas! to preserve this medium, between mouthing, and meaning too little, to keep the attention more pleasingly awake, by a tempered spirit, than by mere vehemence of voice, is of all the master-strokes of an actor the most difficult to reach. In this none yet have equalled Betterton. But I am unwilling to show his superiority only by recounting the errors of those, who now cannot answer to them, let their farther failings therefore be forgotten! or rather, shall I in some measure excuse them! For I am not yet sure, that they might not be as much owing to the false judgment of the spectator, as the actor. While the million are so apt to be transported, when the drum of their ear is so roundly rattled; while they take the life of elocution to lie in the strength of the lungs, it is no wonder the actor, whose end is applause, should be also tempted, at this easy rate, to excite it. Shall I go a little farther? and allow that this extreme is more pardonable than its opposite error? I mean that dangerous affectation of the monotone, or solemn sameness of pronunciation, which to my ear is insupportable; for of all faults that so frequently pass upon the vulgar, that of flatness will have the fewest admirers. That this is an error of ancient standing seems evident by what Hamlet says, in his instructions to the players, viz.

Be not too tame, neither, &c.The actor, doubtless, is as strongly tied down to the rules of Horace as the writer:

Si vis me flere, dolendum estPrimum ipsi tibi —He that feels not himself the passion he would raise, will talk to a sleeping audience: but this never was the fault of Betterton; and it has often amazed me to see those who soon came after him, throw out in some parts of a character, a just and graceful spirit, which Betterton himself could not but have applauded. And yet in the equally shining passages of the same character, have heavily dragged the sentiment along like a dead weight; with a long-toned voice, and absent eye, as if they had fairly forgot what they were about. If you have never made this observation, I am contented you should not know where to apply it.

“A farther excellence in Betterton, was, that he could vary his spirit to the different characters he acted. Those wild impatient starts, that fierce and flashing fire, which he threw into Hotspur, never came from the unruffled temper of his Brutus (for I have more than once, seen a Brutus as warm as Hotspur) when the Betterton Brutus was provoked, in his dispute with Cassius, his spirit flew only to his eye; his steady look alone supplyed that terror, which he disdained an intemperance in his voice should rise to. Thus, with a settled dignity of contempt, like an unheeding rock, he repelled upon himself the foam of Cassius. Perhaps the very works of Shakspeare will better let you into my meaning:

Must I give way, and room, to your rash choler?Shall I be frighted when a madman stares?And a little after,

There is no terror, Cassius, in your looks! &c.Not but in some part of this scene, where he reproaches Cassius, his temper is not under this suppression, but opens into that warmth which becomes a man of virtue; yet this is that hasty spark of anger, which Brutus himself endeavours to excuse.

“But with whatever strength of nature we see the poet show, at once, the philosopher and the hero, yet the image of the actor’s excellence will be still imperfect to you, unless language could put colours in our words to paint the voice with.

“Et, si vis similem pingere, pinge sonum, is enjoining an impossibility. The most that a Vandyke can arrive at, is to make his portraits of great persons seem to think; a Shakspeare goes farther yet, and tells you what his pictures thought; a Betterton steps beyond them both, and calls them from the grave, to breathe, and be themselves again, in feature, speech, and motion. When the skilful actor shows you all these powers at once united, and gratifies at once your eye, your ear, your understanding. To conceive the pleasure rising from such harmony, you must have been present at it! ’tis not to be told you!

“There cannot be a stronger proof of the charms of harmonious elocution, than the many, even unnatural scenes and flights of the false sublime it has lifted into applause. In what raptures have I seen an audience, at the furious fustian and turgid rants in Nat. Lee’s Alexander the Great! for though I can allow this play a few great beauties, yet it is not without its extravagant blemishes. Every play of the same author has more or less of them. Let me give you a sample from this. Alexander, in a full crowd of courtiers, without being occasionally called or provoked to it, falls into this rhapsody of vainglory:

Can none remember? Yes, I know all must!And therefore they shall know it again.

When Glory, like a dazzling eagle, stoodPerched on my beaver, in the Granic flood,When Fortune’s self, my standard trembling bore,And the pale Fates stood frighted on the shore,When the immortals on the billows rode,And I myself appeared the leading god.When these flowing numbers come from the mouth of a Betterton, the multitude no more desired sense to them, than our musical connoisseurs think it essential in the celebrated airs of an Italian opera. Does not this prove, that there is very near as much enchantment in the well-governed voice of an actor, as in the sweet pipe of a eunuch? If I tell you, there was no one tragedy, for many years, more in favour with the town than Alexander, to what must we impute this its command of public admiration? not to its intrinsic merit, surely, if it swarms with passages like this I have shown you! If this passage has merit, let us see what figure it would make upon canvas, what sort of picture would rise from it. If Le Brun, who was famous for painting the battles of this hero, had seen this lofty description, what one image could he have possibly taken from it? In what colours would he have shown us Glory perched upon a beaver? how would he have drawn Fortune trembling? or, indeed, what use could he have made of pale Fates, or immortals riding upon billows, with this blustering god of his own making at the head of them! where, then, must have lain the charm, that once made the public so partial to this tragedy? why plainly, in the grace and harmony of the actor’s utterance. For the actor himself is not accountable for the false poetry of his author; that, the hearer is to judge of; if it passes upon him, the actor can have no quarrel to it; who, if the periods given him are round, smooth, spirited, and high-sounding, even in a false passion, must throw out the same fire and grace, as may be required in one justly rising from nature; where those his excellencies will then be only more pleasing in proportion to the taste of his hearer. And I am of opinion, that to the extraordinary success of this very play, we may impute the corruption of so many actors, and tragic writers, as were immediately mislead by it. The unskilful actor, who imagined all the merit of delivering those blazing rants, lay only in the strength, and strained exertion of the voice, began to tear his lungs, upon every false, or slight occasion, to arrive at the same applause. And it is hence I date our having seen the same reason prevalent, for above fifty years. Thus equally misguided too, many a barren-brained author has streamed into a frothy flowing style, pompously rolling into sounding periods, signifying – roundly nothing; of which number, in some of my former labours, I am something more than suspicious, that I may myself have made one, but to keep a little closer to Betterton.

“When this favourite play I am speaking of, from its being too frequently acted, was worn out, and came to be deserted by the town, upon the sudden death of Monfort, who had played Alexander with success, for several years, the part was given to Betterton, which, under this great disadvantage of the satiety it had given, he immediately revived with so new a lustre, that for three days together it filled the house; and had his then declining strength been equal to the fatigue the action gave him, it probably might have doubled its success; an uncommon instance of the power and intrinsic merit of an actor. This I mention not only to prove what irresistible pleasure may arise from a judicious elocution, with scarce sense to assist it; but to show you too, that though Betterton never wanted fire, and force, when his character demanded it; yet, where it was not demanded, he never prostituted his power to the low ambition of a false applause. And further, that when, from a too advanced age, he resigned that toilsome part of Alexander, the play, for many years after never was able to impose upon the public; and I look upon his so particularly supporting the false fire and extravagancies of that character, to be a more surprizing proof of his skill, than his being eminent in those of Shakspeare; because there, truth and nature coming to his assistance he had not the same difficulties to combat, and consequently, we must be less amazed at his success, where we are more able to account for it.

(To be continued.)DRAMATIC CENSOR

I have always considered those combinations which are formed in the playhouse as acts of fraud or cruelty: He that applauds him who does not deserve praise, is endeavouring to deceive the public; He that hisses in malice or in sport is an oppressor and a robber.

Dr. Johnson’s Idler, No. 25.PHILADELPHIA THEATRE

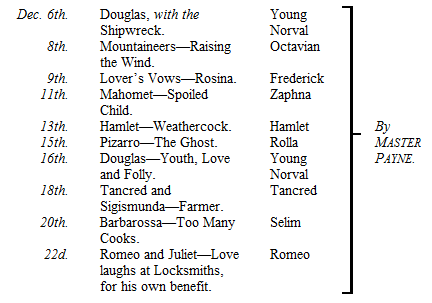

All those plays are well known. From the peculiar circumstances attending their performance they call for a share of particular attention, which would otherwise be superfluous. Where there is something new, and much to be admired, it would be inexcusable to be niggard of our labour, even were the labour painful, which in this instance it is not. The performance of Master Payne pleased us so much that we have often since derived great enjoyment from the recollection of it; and to retrace upon paper the opinions with which it impressed us, we now sit down with feelings very different from those, which, at one time, we expected to accompany the task. Without the least hesitation we confess, that when we were assured it would become our duty to examine that young gentleman’s pretensions, and compare his sterling value with the general estimate of it, as reported from other parts of the union, we felt greatly perplexed. On one hand strict critical justice with the pledge which is given in our motto, imperiously forbidding us to applaud him who does not deserve it, stared us in the face with a peremptory inhibition from sacrificing truth to ceremony, or prostrating our judgment before the feet of public prejudice: while, on the other we were aware that nothing is so obstinate as error – that fashionable idolatry is of all things the most incorrigible by argument, and the least susceptible of conviction – that while the dog-star of favouritism is vertical over a people, there is no reasoning with them to effect; and that all the efforts of common sense are but given to the wind, if employed to undeceive them, till the brain fever has spent itself, and the public mind has settled down to a state of rest. We had heard Master Payne’s performances spoken of in a style which quite overset our faith. Not one with whom we conversed about him spoke within the bounds of reason: few indeed seemed to understand the subject, or, if they did, to view it with the sober eye of plain common rationality. The opinions of some carried their own condemnation in their obvious extravagance; and hyperbolical admiration fairly ran itself out of breath in speaking of the wonders of this cisatlantic young Roscius.

While we knew that half of what was said was utterly impossible, we thought it due to candor to believe that such a general opinion could not exist without some little foundation; that in all likelihood the boy had merit, considerable for his years and means, to which his puerility might have given a peculiar recommendation, and that when he came to be unloaded by time and public reflection of that injurious burthen of idolatrous praise, which to our thinking had all the bad effects of calumny, we should be able to find at bottom something that could be applauded without impairing our veracity, deceiving the public, or joining the multitude in burning the vile incense of flattery under the boy’s nose, and hiding him from the world and from himself in a cloud of pernicious adulation.

But how to encounter this reigning humour was the question: to render his reasoning efficacious, the critic must take care not to make it unpalatable. And here the general taste seemed to be in direct opposition to our reason and experience; for we had not yet (even in the case of young Betty, with the aggregate authority of England, Ireland, and Scotland in his favour) been free from scepticism: the Roscio-mania contagion had not yet infected us quite so much: in a word, we had no faith in miracles, nor could we, in either the one case or the other, screw up our credulity to any sort of unison with the pitch of the multitude. We shall not readily forget the mixed sensations of concern and risibility with which, day after day, from the first annunciation of Master Payne’s expected appearance at Philadelphia, we were obliged to listen to the misjudging applause of his panegyrists. There is a narrowness of heart, and a nudity of mind too common in our nature, under the impulse of which few people can bring themselves to do homage to one person without magnifying their incense by the depreciation of some other. According to these a favourite has not his proper station, till all others are put below him; as if there was no merit positive, but all was good but by comparison. In this temper there certainly is at least as much malice to one as kindness to the other: but an honourable and beneficent wisdom gives other laws for human direction, and dictates that in the house of merit there are not only many stories, but many apartments in each story: and that every man may be fairly adjudicated all the praise he deserves without thrusting others down into the ground floor to make room for him. Yet not one in twenty could we find to praise Master Payne, without doing it at the expense of others. “He is superior to Cooper,” said one; “he speaks better than Fennell,” said a second: these sagacious observations too, are rarely accompanied by a modest qualification, such as “I think,” or “it is my opinion” – but nailed down with a peremptory is. This is the mere naked offspring of a muddy or unfinished mind, which, for want of discrimination to point out the particular beauties it affects to admire, accomplishes its will by a sweeping wholesale term of comparison, more injurious to him they praise than to him they slight. Nay, so far has this been carried, that some who never were out of the limits of this union have, by a kind of telescopical discernment, viewed Cooke and Kemble in comparison with their new favourite, and found them quite deficient. We cannot readily forget one circumstance: a person said to another in our hearing at the playhouse, “You have been in England, sir, don’t you think Master Payne superior to young Betty?” “I don’t know, sir, having never seen Master Betty,” answered the man; “I think he is very much superior,” replied the former – “You have seen Master Betty then, sir,” said the latter; “No, I never did,” returned he that asked the first question, “but I am sure of it – I have heard a person that was in England say so!!” – This was the pure effusion of a mind subdued to prostration by wonder. In England this was carried to such lengths, that the panegyrists of young Betty seemed to vie with each other in fanatical admiration of that truly extraordinary boy. One, in a public print, went so far as to assert, that Mr. Fox (who, as well as Mr. Pitt, was at young Betty’s benefit when he played Hamlet) declared the performance was little, if at all, inferior to that of his deceased friend Garrick. With the very same breath in which we read the paragraph we declared it to be a falsehood. Mr. Fox had too much judgment to institute the comparison – Mr. Fox had too much benignity to utter such a malicious libel upon that noble boy.

These considerations naturally augmented our anxiety, and we did most heartily wish, if it were possible, to be relieved from the task of giving an opinion of Master Payne. For in addition to his youthfulness, we knew that he wanted many advantages which young Betty possessed. The infant Roscius of England, had, from his very infancy, been in a state of the best discipline; being from the time he was five years of age, daily exercised in recitation of poetry, by his mother, who shone in private theatricals; and having been afterwards prepared for the stage, and hourly tutored by Mr. Hough, an excellent preceptor. By his father too, who is one of the best fencers in Europe, he was improved in gracefulness of attitude – and nature had uncommonly endowed him for the reception of those instructions. Of such means of improvement Master Payne was wholly destitute, for there was not a man that we could hear of in America who was at once capable and willing to instruct him. Self-dependent and self-taught as he must be, we could see no feasible means by which he could evolve his powers, be they what they might, to adequate effect for the stage. We deemed it scarcely possible that he could have got rid of the innumerable provincialisms which must cling to his youth: and we laid our account at the best with meeting a fine forward boy who would speak, perhaps not very well either, by rote; and taking the most prominent favourite actor of his day, as a model, be a mere childish imitator. We considered that when young people do any thing with an excellence disproportioned to their years, they are viewed through a magnifying medium; and that being once seen to approach to the perfection of eminent adults, they are, by a transition sufficiently easy to a wondering mind, readily concluded to excel them. Thus Betty was said to surpass Kemble and Cooke; and thus young Payne was roundly asserted to surpass Cooper and Fennell. Such were the feelings and opinions with which we met Master Payne on his first appearance, for which the tragedy of Douglas was judiciously selected; and we own that the first impression he made upon our minds was favourable to his talents in this way: He appeared to be just of that age which we should think least advantageous to him; too young to enforce approbation by robust manly exertion of talents; too far advanced to win over the judgment by tenderness; or by a manifest disproportion between his age and his efforts, to excite that astonishment which, however shortlived, is, while it lasts, despotic over the understanding. Labouring, therefore, under most of the disadvantages without any of the advantages of puerility, candor and common sense pronounced at once that much less of the estimation in which he was held, was to be ascribed to his boyishness, and of course much more to his talents than we had been led to imagine. If, therefore, he got through the character handsomely, and still carried the usual applause along with him, we directly conceived that there would be just ground for thinking it not entirely the result of prejudice, nor by any means undeserved.

At his entrance he seemed a little intimidated, as if he were dubious of his reception; nor could he for some minutes devest himself of that feeling, though he was received with the most flattering welcome; – this transient perturbation gave a very pleasing effect to his first words; and when he said, “My name is Norval,” he uttered it with a pause which seemed to be the effect of the modest diffidence natural to such a character upon being introduced into a higher presence than he had ever before approached. Had this been the effect of art it would have been fine – perhaps it was – but we thought it was accidental.

The utter impossibility of a beardless boy of sixteen or seventeen years, at all assimilating to the character of a warrior and mighty slayer of men, is of itself an insuperable obstacle to the complete personification of certain characters by a young gentleman of the age and stature of Master Payne. He might speak them with strict propriety – he might act them with feeling and spirit; but had he the general genius of Garrick – the energies of Mossop – the beauty of Barry, the elocution of Sheridan, and the art of Kemble, he could not with the feminine face and voice, and the unfinished person inseparable from such tender years, personate them: nor so long as he is seen or heard can the perception of his nonage be excluded, or he be thought to represent that character, to the formation of which, not gristle, nor fair, round soft lineaments, but huge bone and muscle, well-knit joints, knotty limbs, and the hard face of Mars are necessary. If we find, as we do in many great works of criticism, objections made to the performance of several characters by actors of high renown merely for their deficiency in personal appearance – if the externals of Mr. Garrick are stated by his warmest panegyrists as unfitting him for characters of dignity or heroism, even to his exclusion from Faulconbridge, Hotspur, &c. and if we find that the greatest admirers of Barry considered the harmony and softness of his features, as reducing his Macbeth, Pierre, &c. to poor lukewarm efforts, how can it be expected that a boy, just started from childhood, should present a true picture of a warrior or a philosopher? We premise this for the purpose of having it understood that what we are to say of Master Payne is to be subject to these deductions, and that in the praise which it is but just to bestow upon him, we exclude all idea of external resemblance to the characters. Of the mental powers, the informing spirit, the genius, the feeling which he now discloses, and the rich promise they afford of future greatness – of these it is, we profess to speak: further we cannot go without insincerity, untruth, and manifest absurdity.