полная версия

полная версияThe Psychology of Salesmanship

An important factor in getting past the stockade of the outer office is the consciousness of Self Respect and the realization of the "I" of which we have spoken. This mental attitude impresses itself upon those who guard the outer works, and serves to clear the way. As Pierce says: "Remember, you are asking no favors; that you have nothing to apologize for, and that you have every reason in the world for holding your head high. And it is wonderful what this holding up of the head will do in the way of increasing sales. We have seen salesmen get entrance to the offices of Broadway buyers simply through the holding of the head straight up from the shoulders." But it is the Mental Attitude back of the physical expression that is the spirit of the thing – don't forget this.

The Mental Attitude and the physical expression thereof instinctively influence the conduct of other people toward one. We may see the same thing illustrated in the attitude and action of the street boy toward dogs. Let some poor cur trot along with drooping ears, timid expression, meek eyes, and tail between his legs, and the urchin will be apt to kick him or throw a rock at his retreating form. Note the difference when the self-respecting dog, with spirit in him, trots past, looking the boy fearlessly in the eye and showing his sense of self-respect and power to back it up in every movement. That dog is treated accordingly. There are certain people whose manner is such that they do not need to ask respect and consideration – it is given them as a matter of right and privilege. People stand aside to give them room, and move up in street cars that they may have a seat. And it does not necessarily follow that the person to whom this respect is shown is a worthy individual or a person of fine qualities – he may be a confidence man or a swindler. But whatever he is, or may be, he has certain outward mannerisms and characteristics which enable him to "put up a good front" and which carry him through. At the back of it all will be found certain mental states which produce the genuine outward characteristics and manner in the case of genuine instances of persons possessing authority and high position, the confidence man merely presenting a passable counterfeit, being a good actor.

It is often necessary for the salesman to send in a card to the inner office. It is well for him to have some cards, well engraved in the most approved manner, bearing simply his name: "Mr. John Jay Jones," with his business appearing thereon. If he is travelling from a large city, and is selling in smaller towns, he may have "New York," "Chicago," "Philadelphia," "Boston," etc., as the case may be in the corner of his card. If the name of his business appears on the card the prospect often goes over the matter of a possible sale, mentally, without the salesman being present to present his case, and then may decline to grant an interview. The name, without the business, often arouses interest or curiosity and thus, instead of hindering, really aids in securing the interview.

Regarding the discussion of the business with anyone other than the prospect himself, the authorities differ. As a matter of fact it would seem to depend largely upon the particular circumstances of each case, the nature of the articles to be sold, and the character and position of the subordinate in question.

One set of authorities hold that it is very poor policy to tell your business to a subordinate, and that it is far better to tell him courteously but firmly that your business is of such a nature that you can discuss it only with the prospect in person. Otherwise, it is held that the subordinate will tell you that the matter in question has already been considered by his principal, and that he is fully informed regarding the proposition, and has given orders that he is not to be disturbed further regarding it.

The other set of authorities hold that in many cases the subordinate may be pressed into service, by treating him with great respect, and an apparent belief in his judgment and authority, winning his good-will and getting him interested in your proposition, and endeavoring to have him "speak about it" to his superior during the day. It is claimed that a subsequent call, the day following, will often prove successful, as the subordinate will have paved the way for an interview and have actually done some work for you in the way of influence and selling talk. It is held that some salesmen have made permanent "friends in camp" of these subordinates who have been approached in this way.

It would seem, however, as we have said, to depend much upon the particular circumstances of the case. In some cases the subordinate is merely a "hold-off," or "breakwater;" while in others he is a confidential employee whose opinion has weight with the prospect, and whose good-will and aid are well worth securing. In any event, however, it is well to gain the respect and good-will of those in the "outer court," for they can often do much in the way of helping or injuring your chances. We have known cases in which subordinates "queered" a salesman who had offended them; and we have known other cases in which the subordinate being pleased by the salesman "put him next." It is always better to make a friend rather than an enemy – from the office-boy upward – on general principles. Many a fine warrior has been tripped up by a small pebble. Strong men have died from the bite of a mosquito.

The following advice from J.F. Gillen, the Chicago manager of the Burroughs Adding Machine Company, is very much to the point. Mr. Gillen, in the magazine "Salesmanship," says: "A salesman who has not proved his mettle – and who, unfortunately, is not sure of himself – is likely to be overcome by a sense of his own insignificance on entering the private domain of the great man, rich man, or influential man, from whom he hopes to get an order. The very hum and rush of business in this boss's office are very awe-inspiring. The fact that there exists an iron-clad rule, designed to protect the boss against intrusion, forbidding the admittance of an uninvited salesman – and the fact that the army of employees are bound by this rule to oppose the entrance of any such visitor – combine to make an untried salesman morally certain of his powerlessness; to make him feel that he has no justifiable reason for presenting himself at all. Indeed he has none, if the awe which he feels for red-tape, rules, dignitaries, has made him lose sight of the attractions of his own proposition; has swallowed up his confidence in what he has to offer and his ability to enthuse the prospect in regard to it. * * * If you believe that your proposition will prove interesting to the prospect and that he will profit by doing business with you, you have a right to feel that the rule barring salesmen from his presence was not intended to bar you. Convince yourself of this and the stern negative of the information clerk will not abash you. You will find yourself endowed with a courage and resourcefulness to cope with a slick secretary who gives glibly evasive replies when you try to find out whether Mr. Prospect is now in his office, whether he cannot see you at once, and what reason exists for supposing you could possibly tell your business to any subordinate in place of him. Once you are thus morally sure of your ground, the hardest part of the battle is won. * * * You can see the prospect and get speech with him, no matter what obstacles intervene, if your nerve holds out and you use your brains."

Remember this, always: The Psychology of Salesmanship applies not only to work with the prospect, but also to work with those who bar the way to him. Subordinates have minds, faculties, feelings and strong and weak points of mentality – they have their psychology just as their employer has his. It will pay you to make a careful study of their psychology – it has its rules, laws and principles. This is a point often overlooked by little salesmen, but fully recognized by the "big" ones. The short cut to the mind of many a prospect is directly through the mind of the man in the outer office.

CHAPTER VII

THE PSYCHOLOGY OF PURCHASE

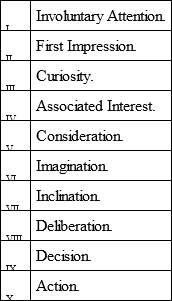

There are several stages or phases manifested by the buyer in the mental process which results in a purchase. While it is difficult to state a hard and fast rule regarding the same, because of the variety of temperament, tendencies and mental habits possessed in several degrees by different individuals, still there are certain principles of feeling and thought manifested alike by each and every individual buyer, and a certain logical sequence is followed by all men in each and every original purchase. It follows, of course, that these principles, and this sequence, will be found to be operative in each and every original purchase, whether that purchase be the result of an advertisement, display of goods, recommendation, or the efforts of a salesman. The principle is the same in each and every case, and the sequence of the mental states is the same in each and every instance. Let us now consider these several mental states in their usual sequence.

The several mental states manifested by every buyer in an original purchase are given below in the order of sequence in which they are usually manifested: —

We use the term "original purchase" in this connection in order to distinguish the original purchase from a repeated order or subsequent purchase of the same article, in which latter instance the mental process is far more simple and which consists merely in recognizing the inclination, or habit, and ordering the goods, without repeating the original complex mental operation. Let us now proceed to a consideration of the several mental stages of the original purchase, in logical sequence: —

I. Involuntary Attention. This mental state is the elementary phase of attention. Attention is not a faculty of the mind, but is instead the focusing of the consciousness upon one object to the temporary exclusion of all other objects. It is a turning of the mind on an object. The object of attention may be either external, such as a person or thing; or internal, such as a feeling, thought, memory, or idea. Attention may be either voluntary, that is, directed consciously by the will; or involuntary, that is, directed unconsciously and instinctively and apparently independently of the will. Voluntary attention is an acquired and developed power and is the attribute of the thinker, student and intellectual individual in all walks of life. Involuntary attention, on the contrary, is but little more than a reflex action, or a nervous response to some stimulus. As Halleck says: "Many persons scarcely get beyond the reflex stage. Any chance stimulus will take their attention away from their studies or their business." Sir William Hamilton made a still finer distinction, which is, however, generally overlooked by writers on the subject, but which is scientifically correct and which we shall follow in this book. He holds that there are three degrees or kinds of attention: (1) the reflex or involuntary, which is instinctive in nature; (2) that determined by desire or feeling, which partakes of both the involuntary and voluntary nature, and which although partly instinctive may be resisted by the will under the influence of the judgment; and (3) that determined by deliberate volition in response to reason, as in study, scientific games, rational deliberation, etc.

The first mental step of the purchase undoubtedly consists of involuntary or reflex attention, such as is aroused by a sudden sound, sight, or other sensation. The degree of this involuntary attention depends upon the intensity, suddenness, novelty, or movement of the object to which it responds. All persons respond to the stimuli arousing this form of attention, but in different degrees depending upon the preoccupation or concentration of the individual at the time. The striking or novel appearance of an advertisement; the window-display of goods; the appearance of the salesman – all these things instinctively arouse the involuntary attention, and the buyer "turns his mind on" them. But this turning the mind on belongs to Hamilton's first class – that of the instinctive response to the sight or sound, and not that aroused by desire or deliberate thought. It is the most elemental form of attention or mental effort, and to the salesman means simply: "Well, I see you!" Sometimes the prospect is so preoccupied or concentrated on other things that he barely "sees" the salesman until an added stimulus is given by a direct remark.

II. First Impression. This mental state is the hasty generalization resulting from the first impression of the object of attention – the advertisement, suggestion, display of goods, or the Salesman – depending in the last case upon the general appearance, action, manner, etc., as interpreted in the light of experience or association. In other words, the prospect forms a hasty general idea of the thing or person, either favorable or unfavorable, almost instinctively and unconsciously. The thing or person is associated or classed with others resembling it in the experience and memory of the prospect, and the result is either a good, bad or indifferent impression resulting from the suggestion of association. For this reason the ad. man and the window dresser endeavor to awaken favorable and pleasing associated memories and suggestions, and "puts his best foot foremost." The Salesman endeavors to do the same, and seeks to "put up a good front" in his Approach, in order to secure this valuable favorable first impression. People are influenced more than they will admit by these "first impressions," or suggestions, of appearance, manner, etc., and the man who understands psychology places great importance upon them. A favorable first impression smooths the way for the successful awakening of the later mental states. An unfavorable first impression, while it may be removed and remedied later, nevertheless is a handicap which the Salesman should avoid.

(Note: The mental process of the purchase now passes from the stage of involuntary attention, to that of attention inspired by desire and feeling which partakes of both the voluntary and involuntary elements. The first two stages of this form of attention are known as Curiosity and Associated Interest, respectively. In some cases Curiosity precedes, in others Associated Interest takes the lead, as we shall see. In other cases the manifestation of the two is almost simultaneous.)

III. Curiosity. This mental state is really a form of Interest, but is more elemental than Associated Interest, being merely the interest of novelty. It is the strongest item of interest in the primitive races, in children, and in many adults of elemental development and habits of thought. Curiosity is the form of Interest which is almost instinctive, and which impels one to turn the attention to strange and novel things. All animals possess it to a marked degree, as trappers have found out to their profit. Monkeys possess it to an inordinate degree, and the less developed individuals of the human race also manifest it to a high degree. It is connected in some way with the primitive conditions of living things, and is probably a heritage from earlier and less secure conditions of living, where inquisitiveness regarding new, novel and strange sights and sounds was a virtue and the only means of acquiring experience and education. At any rate, there is certainly in human nature a decided instinctive tendency to explore the unknown and strange – the attraction of the mysterious; the lure of the secret things; the tantalizing call of the puzzle; the fascination of the riddle.

The Salesman who can introduce something in his opening talk that will arouse Curiosity in the prospect has done much to arouse his attention and interest. The street-corner fakir, and the "barker" for the amusement-park show, understand this principle in human nature, and appeal largely to it. They will blindfold a boy or girl, or will make strange motions or sounds, in order to arouse the curiosity of the crowd and to cause them to gather around – all this before the actual appeal to interest is made. In some buyers Curiosity precedes Associated Interest – the interest in the unknown and novel precedes the practical interest. In others the Associated Interest – the practical interest inspired by experience and association – precedes Curiosity, the latter manifesting simply as inquisitiveness regarding the details of the object which has aroused Associated Interest. In other cases, Curiosity and Associated Interest are so blended and shaded into each other that they act almost as one and simultaneously. On the whole, though, Curiosity is more elemental and crude than Associated Interest, and may readily be distinguished in the majority of cases.

IV. Associated Interest. This mental state is a higher form of interest than Curiosity. It is a practical interest in things relating to one's interests in life, his weal or woe, loves or hates, instead of being the mere interest in novelty of Curiosity. It is an acquired trait, while Curiosity is practically an instinctive trait. Acquired Interest develops with character, occupation, and education, while Curiosity manifests strongly in the very beginnings of character, and before education. Acquired Interest is manifested more strongly in the man of affairs, education and experience, while Curiosity has its fullest flower in the monkey, savage, young child and uncultured adult. Recognizing the relation between the two, it may be said that Curiosity is the root, and Associated Interest the flower.

Associated Interest depends largely upon the principle of Association or Apperception, the latter being defined as "that mental process by which the perceptions or ideas are brought into relation to our previous ideas and feelings, and thus are given a new clearness, meaning and application." Apperception is the mental process by which objects and ideas presented to us are perceived and thought of by us in the light of our past experience, temperament, tastes, likes and dislikes, occupation, interest, prejudices, etc., instead of as they actually are. We see everything through the colored glasses of our own personality and character. Halleck says of Apperception: "A woman may apperceive a passing bird as an ornament to her bonnet; a fruit grower, as an insect killer; a poet, as a songster; an artist, as a fine bit of coloring and form. The housewife may apperceive old rags as something to be thrown away; a ragpicker, as something to be gathered up. A carpenter, a botanist, an ornithologist, a hunter, and a geologist walking through a forest would not see the same things." The familiar tale of the text-books illustrates this principle. It relates that a boy climbed up a tree in a forest and watched the passers-by, and listened to their conversation. The first man said: "What a fine stick of timber that tree would make." The boy answered: "Good morning, Mr. Carpenter." The second man said: "That is fine bark." The boy answered: "Good morning, Mr. Tanner." The third man said: "I'll bet there's squirrels in that tree." The boy answered: "Good morning, Mr. Hunter." Each and every one of the men saw the tree in the light of his personal Apperception or Associated Interest.

Psychologists designate by the term "the apperceptive mass" the accumulated previous experiences, prejudices, temperament, inclination and desires which serve to modify the new perception or idea. The "apperceptive mass" is really the "character" or "human nature" of the individual. It necessarily differs in each individual, by reason of the great variety of experiences, temperament, education, etc., among individuals. Upon a man's "apperceptive mass," or character, depends the nature and degree of his interest, and the objects which serve to inspire and excite it.

It follows then that in order to arouse, induce and hold this Associated Interest of the prospect, the Salesman must present things, ideas or suggestions which will appeal directly to the imagination and feelings of the man before him, and which are associated with his desires, thoughts and habits. If we may be pardoned for the circular definition we would say that one's Associated Interest is aroused only by interesting things; and that the interesting things are those things which concern his interests. A man's interests always interest him – and his interests are usually those things which concern his advantage, success, personal well-being – in short his pocketbook, social position, hobbies, tastes, and satisfaction of his desires. Therefore the Salesman who can throw the mental spot-light on these interesting things, may secure and hold one's Associated Interest. Hence the psychology of the repeated statement: "I can save you money;" "I can increase your sales;" "I can reduce your expenses;" "I have something very choice;" or "I can give you a special advantage," etc.

It may as well be conceded that business interest is selfish interest, and not altruistic. In order to interest a man in a business proposition he must be shown how it will benefit him in some way. He is not running a philanthropic institution, or a Salesman's Relief Fund, nor is he in business for his health – he is there to make money, and in order to interest him you must show him something to his advantage. And the first appeal of Associated Interest is to his feeling of Self Interest. It must be in the nature of the mention of "rats!" to a terrier, or "candy!" to a child. It must awaken pleasant associations in his mind, and pleasing images in his memory. If this effect is produced, he can be speedily moved to the succeeding phases of Imagination and Inclination. As Halleck says: "All feeling tends to excite desire. * * * A representative image of the thing desired is the necessary antecedent to desire. If the child had never seen or heard of peaches he would have no desire for them." And, following this same figure, we may say that if the child has a taste for peaches he will be interested in the idea of peaches. And so when you say "peaches!" to him you have his Associated Interest, which will result in a mental image of the fruit followed by a desire to possess it, and he will listen to your talk regarding the subject of "peaches."

The following are the general psychological rules regarding Associated Interests:

I. Associated Interest attaches only to interesting things – that is to things associated with one's general desires and ideas.

II. Associated Interest will decline in force and effect unless some new attributes or features are presented – it requires variety in presentation of its object.

Macbain says: "One of the old time salesmen who used to sell the trade in the Middle West, beginning some thirty years ago, and following that vocation for several decades, used as his motto, 'I am here to do you good.' He did not make his statement general, either, in telling his customers how he could do it. He got right down to the vital affairs which touched his customers. He demonstrated it to them, and this personal demonstration is the kind that makes the sales."

Remember, always, that the phase of Associated Interest in a purchase is not the same as the phase of Demonstration and Proof. It is the "warming up" process, preceding the actual selling talk. It is the stage of "thawing out" the prospect and melting the icy covering of prejudice, caution and reluctance which encases him. Warm up your prospect by general statements of Associated Interest, and blow the coals by positive, brief, pointed confident statements of the good things you have in store for him. And, finally, remember that the sole purpose of your efforts at this state is to arouse in him the mental state of INTERESTED EXPECTANT ATTENTION! Keep blowing away at this spark until you obtain the blaze of Imagination and the heat of Desire.

V. Consideration. This mental state is defined as: "An examination, inquiry, or investigation into anything." It is the stage following Curiosity and Associated Interest, and tends toward an inquiry into the thing which has excited these feelings. Consideration, of course, must be preceded and accompanied by Interest. It calls for the phase of Attention excited by feeling, but a degree of voluntary attention is also manifested therewith. It is the "I think I will look into this matter" stage of the mental process of purchase. It is usually evidenced by a disposition to ask questions regarding the proposition, and to "see what there is to it, anyway." In Salesmanship, this stage of Consideration marks the passing from the stage of Approach on the Salesman's part, to that of the Demonstration. It marks the passage from Passive Interest to Active Interest – from the stage of being "merely interested" in a thing, to that of "interested investigation." Here is where the real selling work of the salesman begins. Here is where he begins to describe his proposition in detail, laying stress upon its desirable points. In the case of an advertisement, or a window display, the mental operation goes on in the buyer's mind in the same way, but without the assistance of the salesman. The "selling talk" of the advertisement must be stated or suggested by its text. If the Consideration is favorable and reveals sufficiently strong attractive qualities in the proposition or article, the mind of the buyer passes on to the next stage of the process which is known as: