полная версия

полная версияMemory: How to Develop, Train, and Use It

There are many cases of record in which extraordinary powers of memory of music have been manifested. Fuller relates the following instances of this particular phase of memory: Carolan, the greatest of Irish bards, once met a noted musician and challenged him to a test of their respective musical abilities. The defi was accepted and Carolan's rival played on his violin one of Vivaldi's most difficult concertos. On the conclusion of the performance, Carolan, who had never heard the piece before, took his harp and played the concerto through from beginning to end without making a single error. His rival thereupon yielded the palm, thoroughly satisfied of Carolan's superiority, as well he might be. Beethoven could retain in his memory any musical composition, however complex, that he had listened to, and could reproduce most of it. He could play from memory every one of the compositions in Bach's 'Well Tempered Clavichord,' there being forty-eight preludes and the same number of fugues which in intricacy of movement and difficulty of execution are almost unexampled, as each of these compositions is written in the most abstruse style of counterpoint.

"Mozart, at four years of age, could remember note for note, elaborate solos in concertos which he had heard; he could learn a minuet in half an hour, and even composed short pieces at that early age. At six he was able to compose without the aid of an instrument, and continued to advance rapidly in musical memory and knowledge. When fourteen years old he went to Rome in Holy Week. At the Sistine Chapel was performed each day, Allegri's 'Miserere,' the score of which Mozart wished to obtain, but he learned that no copies were allowed to be made. He listened attentively to the performance, at the conclusion of which he wrote the whole score from memory without an error. Another time, Mozart was engaged to contribute an original composition to be performed by a noted violinist and himself at Vienna before the Emperor Joseph. On arriving at the appointed place Mozart discovered that he had forgotten to bring his part. Nothing dismayed, he placed a blank sheet of paper before him, and played his part through from memory without a mistake. When the opera of 'Don Giovanni' was first performed there was no time to copy the score for the harpsichord, but Mozart was equal to the occasion; he conducted the entire opera and played the harpsichord accompaniment to the songs and choruses without a note before him. There are many well-attested instances of Mendelssohn's remarkable musical memory. He once gave a grand concert in London, at which his Overture to 'Midsummer Night's Dream' was produced. There was only one copy of the full score, which was taken charge of by the organist of St. Paul's Cathedral, who unfortunately left it in a hackney coach – whereupon Mendelssohn wrote out another score from memory, without an error. At another time, when about to direct a public performance of Bach's 'Passion Music,' he found on mounting the conductor's platform that instead of the score of the work to be performed, that of another composition had been brought by mistake. Without hesitation Mendelssohn successfully conducted this complicated work from memory, automatically turning over leaf after leaf of the score before him as the performance progressed, so that no feeling of uneasiness might enter the minds of the orchestra and singers. Gottschalk, it is said, could play from memory several thousand compositions, including many of the works of Bach. The noted conductor, Vianesi, rarely has the score before him in conducting an opera, knowing every note of many operas from memory."

It will be seen that two phases of memory must enter into the "memory of music" – the memory of tune and the memory of the notes. The memory of tune of course falls into the class of ear-impressions, and what has been said regarding them is also applicable to this case. The memory of notes falls into the classification of eye-impressions, and the rules of this class of memory applies in this case. As to the cultivation of the memory of tune, the principle advice to be given is that the student take an active interest in all that pertains to the sound of music, and also takes every opportunity for listening to good music, and endeavoring to reproduce it in the imagination or memory. Endeavor to enter into the spirit of the music until it becomes a part of yourself. Rest not content with merely hearing it, but lend yourself to a feeling of its meaning. The more the music "means to you," the more easily will you remember it. The plan followed by many students, particularly those of vocal music, is to have a few bars of a piece played over to them several times, until they are able to hum it correctly; then a few more are added; and then a few more and so on. Each addition must be reviewed in connection with that which was learned before, so that the chain of association may be kept unbroken. The principle is the same as the child learning his A-B-C – he remembers "B" because it follows "A." By this constant addition of "just a little bit more," accompanied by frequent reviews, long and difficult pieces may be memorized.

The memory of notes may be developed by the method above named – the method of learning a few bars well, and then adding a few more, and frequently reviewing as far as you have learned, forging the links of association as you go along, by frequent practice. The method being entirely that of eye-impression and subject to its rules, you must observe the idea of visualization – that is learning each bar until you can see it "in your mind's eye" as you proceed. But in this, as in many other eye-impressions, you will find that you will be greatly aided by your memory of the sound of the notes, in addition to their appearance. Try to associate the two as much as possible, so that when you see a note, you will hear the sound of it, and when you hear a note sounded, you will see it as it appears on the score. This combining of the impressions of both sight and sound will give you the benefit of the double sense impression, which results in doubling your memory efficiency. In addition to visualizing the notes themselves, the student should add the appearance of the various symbols denoting the key, the time, the movement, expression, etc., so that he may hum the air from the visualized notes, with expression and with correct interpretation. Changes of key, time or movement should be carefully noted in the memorization of the notes. And above everything else, memorize the feeling of that particular portion of the score, that you may not only see and hear, but also feel that which you are recalling.

We would advise the student to practice memorizing simple songs at first, for various reasons. One of these reasons is that these songs lend themselves readily to memorizing, and the chain of easy association is usually maintained throughout.

In this phase of memory, as in all others, we add the advice to: Take interest; bestow Attention; and Practice and Exercise as often as possible. You may have tired of these words – but they constitute the main principles of the development of a retentive memory. Things must be impressed upon the memory, before they may be recalled. This should be remembered in every consideration of the subject.

CHAPTER XVI

HOW TO REMEMBER OCCURRENCES

The phase of memory which manifests in the recording of and recollection of the occurrences and details of one's every-day life is far more important than would appear at first thought. The average person is under the impression that he remembers very well the occurrences of his every-day business, professional or social life, and is apt to be surprised to have it suggested to him that he really remembers but very little of what happens to him during his waking hours. In order to prove how very little of this kind is really remembered, let each student lay down this book, at this place, and then quieting his mind let him endeavor to recall the incidents of the same day of the preceding week. He will be surprised to see how very little of what happened on that day he is really capable of recollecting. Then let him try the same experiment with the occurrences of yesterday – this result will also excite surprise. It is true that if he is reminded of some particular occurrence, he will recall it, more or less distinctly, but beyond that he will remember nothing. Let him imagine himself called upon to testify in court, regarding the happenings of the previous day, or the day of the week before, and he will realize his position.

The reason for his failure to easily remember the events referred to is to be found in the fact that he made no effort at the time to impress these happenings upon his subconscious mentality. He allowed them to pass from his attention like the proverbial "water from the duck's back." He did not wish to be bothered with the recollection of trifles, and in endeavoring to escape from them, he made the mistake of failing to store them away. There is a vast difference between dwelling on the past, and storing away past records for possible future reference. To allow the records of each day to be destroyed is like tearing up the important business papers in an office in order to avoid giving them a little space in the files.

It is not advisable to expend much mental effort in fastening each important detail of the day upon the mind, as it occurs; but there is an easier way that will accomplish the purpose, if one will but take a little trouble in that direction. We refer to the practice of reviewing the occurrences of each day, after the active work of the day is over. If you will give to the occurrences of each day a mental review in the evening, you will find that the act of reviewing will employ the attention to such an extent as to register the happenings in such a manner that they will be available if ever needed thereafter. It is akin to the filing of the business papers of the day, for possible future reference. Besides this advantage, these reviews will serve you well as a reminder of many little things of immediate importance which have escaped your recollection by reason of something that followed them in the field of attention.

You will find that a little practice will enable you to review the events of the day, in a very short space of time, with a surprising degree of accuracy of detail. It seems that the mind will readily respond to this demand upon it. The process appears to be akin to a mental digestion, or rather a mental rumination, similar to that of the cow when it "chews the cud" that it has previously gathered. The thing is largely a "knack" easily acquired by a little practice. It will pay you for the little trouble and time that you expend upon it. As we have said, not only do you gain the advantage of storing away these records of the day for future use, but you also have your attention called to many important details that have escaped you, and you will find that many ideas of importance will come to you in your moments of leisure "rumination." Let this work be done in the evening, when you feel at ease – but do not do it after you retire. The bed is made for sleep, not for thinking. You will find that the subconsciousness will awaken to the fact that it will be called upon later for the records of the day, and will, accordingly, "take notice" of what happens, in a far more diligent and faithful manner. The subconsciousness responds to a call made upon it in an astonishing manner, when it once understands just what is required of it. You will see that much of the virtue of the plan recommended consists in the fact that in the review there is an employment of the attention in a manner impossible during the haste and rush of the day's work. The faint impressions are brought out for examination, and the attention of the examination and review greatly deepen the impression in each case, so that it may be reproduced thereafter. In a sentence: it is the deepening of the faint impressions of the day.

Thurlow Weed, a well-known politician of the last century, testifies to the efficacy of the above mentioned method, in his "Memoirs." His plan was slightly different from that mentioned by us, but you will at once see that it involves the same principles – the same psychology. Mr. Weed says: "Some of my friends used to think that I was 'cut out' for a politician, but I saw at once a fatal weakness. My memory was a sieve. I could remember nothing. Dates, names, appointments, faces – everything escaped me. I said to my wife, 'Catherine, I shall never make a successful politician, for I cannot remember, and that is a prime necessity of politicians. A politician who sees a man once should remember him forever.' My wife told me that I must train my memory. So when I came home that night I sat down alone and spent fifteen minutes trying silently to recall with accuracy the principal events of the day. I could remember but little at first – now I remember that I could not then recall what I had for breakfast. After a few days' practice I found I could recall more. Events came back to me more minutely, more accurately, and more vividly than at first. After a fortnight or so of this, Catherine said 'why don't you relate to me the events of the day instead of recalling them to yourself? It would be interesting and my interest in it would be a stimulus to you.' Having great respect for my wife's opinion, I began a habit of oral confession, as it were, which was continued for almost fifty years. Every night, the last thing before retiring, I told her everything I could remember that had happened to me, or about me, during the day. I generally recalled the very dishes I had for breakfast, dinner and tea; the people I had seen, and what they had said; the editorials I had written for my paper, giving her a brief abstract of them; I mentioned all the letters I had seen and received, and the very language used, as nearly as possible; when I had walked or ridden – I told her everything that had come within my observation. I found that I could say my lessons better and better every year, and instead of the practice growing irksome, it became a pleasure to go over again the events of the day. I am indebted to this discipline for a memory of unusual tenacity, and I recommend the practice to all who wish to store up facts, or expect to have much to do with influencing men."

The careful student, after reading these words of Thurlow Weed, will see that in them he has not only given a method of recalling the particular class of occurrences mentioned in this lesson, but has also pointed out a way whereby the entire field of memory may be trained and developed. The habit of reviewing and "telling" the things that one perceives, does and thinks during the day, naturally sharpens the powers of future observation, attention and perception. If you are witnessing a thing which you know that you will be called upon to describe to another person, you will instinctively apply your attention to it. The knowledge that you will be called upon for a description of a thing will give the zest of interest or necessity to it, which may be lacking otherwise. If you will "sense" things with the knowledge that you will be called upon to tell of them later on, you will give the interest and attention that go to make sharp, clear and deep impressions on the memory. In this case the seeing and hearing has "a meaning" to you, and a purpose. In addition to this, the work of review establishes a desirable habit of mind. If you don't care to relate the occurrences to another person – learn to tell them to yourself in the evening. Play the part yourself. There is a valuable secret of memory imbedded in this chapter – if you are wise enough to apply it.

CHAPTER XVII

HOW TO REMEMBER FACTS

In speaking of this phase of memory we use the word "fact" in the sense of "an ascertained item of knowledge," rather than in the sense of "a happening," etc. In this sense the Memory of Facts is the ability to store away and recollect items of knowledge bearing upon some particular thing under consideration. If we are considering the subject of "Horse," the "facts" that we wish to remember are the various items of information and knowledge regarding the horse, that we have acquired during our experience – facts that we have seen, heard or read, regarding the animal in question and to that which concerns it. We are continually acquiring items of information regarding all kinds of subjects, and yet when we wish to collect them we often find the task rather difficult, even though the original impressions were quite clear. The difficulty is largely due to the fact that the various facts are associated in our minds only by contiguity in time or place, or both, the associations of relation being lacking. In other words we have not properly classified and indexed our bits of information, and do not know where to begin to search for them. It is like the confusion of the business man who kept all of his papers in a barrel, without index, or order. He knew that "they are all there" but he had hard work to find any one of them when it was required. Or, we are like the compositor whose type has become "pied," and then thrown into a big box – when he attempts to set up a book page, he will find it very difficult, if not impossible – whereas, if each letter were in its proper "box," he would set up the page in a short time.

This matter of association by relation is one of the most important things in the whole subject of thought, and the degree of correct and efficient thinking depends materially upon it. It does not suffice us to merely "know" a thing – we must know where to find it when we want it. As old Judge Sharswood, of Pennsylvania, once said: "It is not so much to know the law, as to know where to find it." Kay says: "Over the associations formed by contiguity in time or space we have but little control. They are in a manner accidental, depending upon the order in which the objects present themselves to the mind. On the other hand, association by similarity is largely put in our own power; for we, in a measure, select those objects that are to be associated, and bring them together in the mind. We must be careful, however, only to associate together such things as we wish to be associated together and to recall each other; and the associations we form should be based on fundamental and essential, and not upon mere superficial or casual resemblances. When things are associated by their accidental, and not by their essential qualities, – by their superficial, and not by their fundamental relations, they will not be available when wanted, and will be of little real use. When we associate what is new with what most nearly resembles it in the mind already, we give it its proper place in our fabric of thought. By means of association by similarity, we tie up our ideas, as it were, in separate bundles, and it is of the utmost importance that all the ideas that most nearly resemble each other be in one bundle."

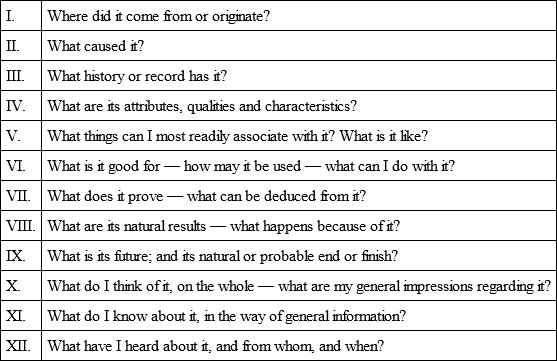

The best way to acquire correct associations, and many of them, for a separate fact that you wish to store away so that it may be recollected when needed – some useful bit of information or interesting bit of knowledge, that "may come in handy" later on – is to analyze it and its relations. This may be done by asking yourself questions about it – each thing that you associate it with in your answers being just one additional "cross-index" whereby you may find it readily when you want it. As Kay says: "The principle of asking questions and obtaining answers to them, may be said to characterize all intellectual effort." This is the method by which Socrates and Plato drew out the knowledge of their pupils, filling in the gaps and attaching new facts to those already known. When you wish to so consider a fact, ask yourself the following questions about it:

If you will take the trouble to put any "fact" through the above rigid examination, you will not only attach it to hundreds of convenient and familiar other facts, so that you will remember it readily upon occasion, but you will also create a new subject of general information in your mind of which this particular fact will be the central thought. Similar systems of analysis have been published and sold by various teachers, at high prices – and many men have considered that the results justified the expenditure. So do not pass it by lightly.

The more other facts that you manage to associate with any one fact, the more pegs will you have to hang your facts upon – the more "loose ends" will you have whereby to pull that fact into the field of consciousness – the more cross indexes will you have whereby you may "run down" the fact when you need it. The more associations you attach to a fact, the more "meaning" does that fact have for you, and the more interest will be created regarding it in your mind. Moreover, by so doing, you make very probable the "automatic" or involuntary recollection of that fact when you are thinking of some of its associated subjects; that is, it will come into your mind naturally in connection with something else – in a "that reminds me" fashion. And the oftener that you are involuntarily "reminded" of it, the clearer and deeper does its impression become on the records of your memory. The oftener you use a fact, the easier does it become to recall it when needed. The favorite pen of a man is always at his hand in a remembered position, while the less used eraser or similar thing has to be searched for, often without success. And the more associations that you bestow upon a fact, the oftener is it likely to be used.

Another point to be remembered is that the future association of a fact depends very much upon your system of filing away facts. If you will think of this when endeavoring to store away a fact for future reference, you will be very apt to find the best mental pigeon-hole for it. File it away with the thing it most resembles, or to which it has the most familiar relationship. The child does this, involuntarily – it is nature's own way. For instance, the child sees a zebra, it files away that animal as "a donkey with stripes;" a giraffe as a "long-necked horse;" a camel as a "horse with long, crooked legs, long neck and humps on its back." The child always attaches its new knowledge or fact on to some familiar fact or bit of knowledge – sometimes the result is startling, but the child remembers by means of it nevertheless. The grown up children will do well to build similar connecting links of memory. Attach the new thing to some old familiar thing. It is easy when you once have the knack of it. The table of questions given a little farther back will bring to mind many connecting links. Use them.

If you need any proof of the importance of association by relation, and of the laws governing its action, you have but to recall the ordinary "train of thought" or "chain of images" in the mind, of which we become conscious when we are day-dreaming or indulging in reverie, or even in general thought regarding any subject. You will see that every mental image or idea, or recollection is associated with and connected to the preceding thought and the one following it. It is a chain that is endless, until something breaks into the subject from outside. A fact flashes into your mind, apparently from space and without any reference to anything else. In such cases you will find that it occurs either because you had previously set your subconscious mentality at work upon some problem, or bit of recollection, and the flash was the belated and delayed result; or else that the fact came into your mind because of its association with some other fact, which in turn came from a precedent one, and so on. You hear a distant railroad whistle and you think of a train; then of a journey; then of some distant place; then of some one in that place; then of some event in the life of that person; then of a similar event in the life of another person; then of that other person; then of his or her brother; then of that brother's last business venture; then of that business; then of some other business resembling it; then of some people in that other business; then of their dealings with a man you know; then of the fact that another man of a similar name to the last man owes you some money; then of your determination to get that money; then you make a memorandum to place the claim in the hands of a lawyer to see whether it cannot be collected now, although the man was "execution proof" last year – from distant locomotive whistle to the possible collection of the account. And yet, the links forgotten, the man will say that he "just happened to think of" the debtor, or that "it somehow flashed right into my mind," etc. But it was nothing but the law of association – that's all. Moreover, you will now find that whenever you hear mentioned the term "association of mental ideas," etc., you will remember the above illustration or part of it. We have forged a new link in the chain of association for you, and years from now it will appear in your thoughts.