полная версия

полная версияThe Awakening of the Desert

On the following morning, while riding our horses over a slight elevation, we came in sight of the swollen current of the Laramie River, which rushed into view from around some highlands not far away at our left; its swiftly flowing waters plunged along before us and onward into those of the North Platte not more than a mile away at our right.

The first view of the scene spread out before us across the river aroused our profound interest, chiefly because the consideration of some very grave questions had caused a large and unusual gathering of warriors to be assembled there, whose conclusions would result either in peace or savage, bloody war. Directly in front of us, and near the opposite bank of the stream, stood the historic old post, Fort Laramie. It consisted of the usual plaza, or parade ground, in the form of a parallelogram, equal in size to an average city block. On each of its four sides were buildings, some of which were two stories in height, some of but one story. It could be clearly seen that of the twenty-five or thirty structures around the square, some were built of logs, others of adobe, and a few were framed.

To the right of these, and wholly removed from the square, were seven or eight long and low buildings each of which we learned later, was used for one of the various trades of carpentry, blacksmithing, horseshoeing, etc., and for quartermasters' supplies. Seemingly not more than three-fourths of a mile beyond the river, a steep but smooth-surfaced bank rose rather abruptly several hundred feet from the river valley to what appeared to be a rough and rocky table-land. Toward our right and up the least abrupt and lowest part of the table-land, were clearly seen the lines of the Oregon trail leading on westward from Laramie over the hills to the Platte River Valley beyond. Somewhat to the left and towering far beyond and above the crest of the high, barren, and treeless table-land, rose Laramie Peak.

All these were then of interest simply as being the framework of the striking picture that lay in the foreground. Extending out to the further margin of the valley beyond the post, also to the right and the left of it on the plain was a city of Indian lodges, each of which stood out a white cone surmounted by its fringe of projecting lodge poles. The lodges appeared to be centered into groups or villages. Parties of Indians, a few only mounted, could be seen in many of the open places.

A flagstaff from which floated our national colors rose from near a corner of the rectangle which indicated the local seat of authority and the quarters for the regimental band.

The river, which was between us and the Fort, was swollen by a flood. It seemed important, however, that we should visit the post and learn as much as possible concerning the pending negotiations with the tribes. Ben, Fred, Pete, and I, therefore, decided to swim the river on horses. The current was exceedingly swift and deep, but though it carried us down stream a long distance, we reached the western bank without serious difficulty. We then wondered how our train would cross. On reaching the post we at once entered the quadrangle and for a few moments watched the movements which were passing before us in that place, which from the beginning of its history had been the most important center for intercourse between the Indians and whites that existed in our country. It was first established in 1834 by Mr. Robert Campbell, a successful fur trader and merchant, whom I have often seen; and as stated by Larpenteur, the river and the post were named in memory of Joaques La Ramie, a French trapper said to have been killed on that stream by the Arapahoes.

The post was purchased in 1849 by the U. S. Government and materially remodeled then, as it has also been since. There was no real fortification to be found at Fort Laramie. A few soldiers were on parade and others were visible around the barracks. We immediately went to headquarters and held interviews with various officials. We were informed that more than 7,000 Indians, consisting of bands of Ogallala and Minnecongoux Sioux, also Cheyennes and Arapahoes, and a few Mountain Crows who were interested in the question at issue, had assembled to participate in the proposed treaty. The officers informed us that the main object to be sought by the Government was the opening of the new route from Fort Laramie to Montana via the head waters of Powder and Big Horn Rivers. The Indians objected to any travel through that country, which was their most valuable hunting ground.

We also learned with pleasure that there was a bridge further down the stream, of which we had not known. We re-crossed the river by swimming our horses. Hitching our teams, we drove to the bridge and after paying three dollars toll for each wagon, crossed upon it and camped on the Platte River bottoms, near the junction of the Laramie and North Platte. The day had been intensely hot, the mercury at the post registering 98 degrees.

Although we had not learned how soon we should be permitted to proceed on our journey, it seemed proper that we should further investigate the progress of affairs and ascertain what was the prospect for peace. We, therefore, again entered the reservation and now interviewed Mr. Seth Ward, who was said to be the best informed man concerning those matters to be found at Laramie. This idea seemed to be quite reasonable, because the military was supposed to be in a sense partisan. We modestly approached the pompous Mr. Ward, who we were told was the sutler. He wore fine clothes, and a soft, easy hat. A huge diamond glittered in his shirt front. He moved quietly round as if he were master of the situation, and with that peculiar air so often affected by men who are financially prosperous and self-satisfied. He seemed to be a good fellow and was in every respect courteous. He assured us that the Indians would be "handled all right" and that there need be no fear of further trouble.

As a business proposition, it was manifestly to the advantage of the sutler and agents that some treaty be made, for the reason that every Indian treaty involves the giving of many presents and other valuable considerations. Whatever the Indians may finally receive become articles of exchange in trade. In this the astute sutler profits largely, as the Indian has little knowledge of the intrinsic value of manufactured goods and the sutler enjoyed exclusive rights of traffic with them at the posts. On the other hand, the soldiers and many others expressed the opinion that no satisfactory agreement would be reached. The demand of the Government as declared to the writer by Colonel, now General H. B. Carrington, was that it should have the right to establish one or more military posts on that road in the country in question. All the Indians occupying that territory were refusing to accept the terms, saying that it was asking too much of their people, in fact it was asking all they had, and it would drive away their game.

While these negotiations were going on with Red Cloud and the leading chiefs, to induce them to yield to the Government the right to establish the military posts, Colonel Carrington arrived at Laramie with about 700 officers and men of the 18th U. S. Infantry. Carrington was then already en route to the Powder River country, to build and occupy the proposed military posts along the Montana road, pursuant to orders from headquarters of the Department of the Missouri, Major General Pope commanding.

The destination and purpose of Colonel Carrington were communicated to the chiefs, who recognized this action on the part of the Government as a determination on its part to occupy the territory regardless of any agreement. Red Cloud and his followers spurned the offers which were made for their birthright and indignantly left the reservation to defend their hunting grounds, and as we then believed and learned later, went immediately on the war path. As stated in the Government reports, they "at once commenced a relentless war against all whites, both citizens and soldiers." The great Chief, Red Cloud, and his followers were now no longer a party to the negotiations, but thousands of other warriors and chiefs were induced to remain.

We later strolled out among the buffalo skin lodges and among the many warriors who were grouped here and there on the level land around the post. The faces of the older Red Men, who still remained, clearly indicated dissatisfaction and defiance.

"And they stood there on the meadowWith their weapons and their war gearPainted like the leaves of autumn,Painted like the sky of morning,Wildly glaring at each other;In their faces stern defiance,In their hearts the feud of ages,The hereditary hatred,The ancestral thirst of vengeance."It appeared finally that in the determination to make some kind of treaty the commissioner brought into council a large number of chiefs, but as the information came to us, they were from bands that did not occupy any part of the country along the route in question. Some of these had resided near Fort Laramie; others, the Brule Sioux, occupied the White Earth River valley; and still others were from along the tributaries of the Kansas River. These bands having no immediate interest in the hunting grounds to the north, were induced to become parties to a treaty. The proceedings so far as concerns the representatives of the Government, seem to have been undignified and unworthy of a great nation. The conclusion of a treaty of peace with these bands, who could not represent the Northern tribes, seemed a farce. The military arm of the Government was in no sense a party to the agreement, their function being solely to protect the whites to the best of their ability. The force at the command of Colonel Carrington was wholly inadequate for this duty. Larpenteur, who appears to have attended many Indian treaties, cites the Laramie treaty of 1851 as one of many in which speculation became the motive for its consummation. The ostensible purpose of that treaty was to accomplish a general peace between all the tribes on the Missouri and Platte Rivers. For that purpose two or three chiefs of each tribe were invited to that treaty. The agents must have known well that the other bands could not be held responsible according to Indian usage when not represented. The fact is stated that the Indians on their return fought with each other before they reached their home, and these dissensions were promptly followed by renewed warfare against the whites.

The treaty of 1866, at which we were present, such as it was, having been concluded by the chiefs of the thousand Indians who remained, the coveted presents were distributed. In a few hours more the friendly camps were ablaze with mounted Indians decked in yellow, red, and other brilliantly colored cheap fabrics flying in the winds. To their simple tastes these tawdry stuffs were more attractive than diamonds. Gilded jewelry was received by them in exchange for articles of real value. We were informed that they received firearms and ammunition, which they greatly prize, but this statement is not made from my personal knowledge.

On one afternoon we were present at what we understood was the council or peace gathering of the bands that had become parties to the treaty. It was apparently necessary that these bands should act somewhat in harmony, and an Indian ratification meeting was quite appropriate. The chiefs and head men, sixty or seventy in number, were seated upon buffalo skins spread upon the ground in a great circle, and behind them in groups stood leading warriors. Among these we were informed were Swift Bear, Spotted Tail, Big Mouth, Standing Elk, and Two Strikes. At the head of the line was a chief apparently much advanced in years, wearing a medal suspended by a leather cord around his neck; his name I am unable to give. The exposed side of the medal bore the insignia of two pipes crossed. During the solemn ceremony about to be performed it hardly seemed proper to scrutinize too closely these emblems of authority, but one of the boys stated he could read the words "James Madison" upon the medal. It was evidently a medal presented at some former treaty and upon it was inscribed the name of the "great father" at Washington.

Treaties were made, according to Government reports, during the administration of Madison in 1816 with the Sioux of the Leaf, the Sioux of the Pine Tops, the Sioux of the River, and other tribes, and this aged chief was doubtless a party to one of these convocations.

While all was silent at the Laramie ceremony that we witnessed, there was handed to this old chief, by a pipe-bearer, with some flourishes which we did not understand, the calumet, a beautiful redstone pipe having a long stem. It was already lighted. Slowly passing the peace pipe to his lips in a serious, dignified manner and with no expression upon his face that could be interpreted, the old chief took from it two or three long drafts with marked intervals between them, and hardly turning his head passed it to the chief who sat at his right, who repeated the ceremony. It was in this manner conveyed from one to another until the circle was completed. The participation in this ceremony doubtless was understood as a pledge of amity between those engaged in it, and as a confirmation of a mutual agreement concerning the matters before them.

It is a fact quite generally recognized by observers of the Indians that there is no custom more universal or more highly valued by the Indian than that of smoking. The pipe is his companion in council; through it he pledges his friends; and with his tomahawk it has its place by him in his grave as his companion in the happy hunting grounds beyond. It is, therefore, not strange that the pipe should be a type of their best handiwork. As stated by Catlin, the red pipe-stone from which all existing specimens of Indian pipes appear to have been made, was obtained from the Pipestone quarry in Minnesota on the dividing ridge between the St. Peters and Missouri Rivers. It was named Catlinite on account of its discovery by George Catlin, the eminent writer and artist, who made it the object of protracted research. Until recent years the quarries have been held as sacred and as neutral ground by the various tribes. It was there, according to Indian tradition, fully described in early records, that the Great Spirit called the Indian nations together and standing upon a precipice of the red pipe rock broke from its wall a piece from which he made a huge pipe. The spirit told them that they must use this rock for their pipes of peace, that it belonged to them all and that the war club must never be lifted on its ground. At the last whiff of his pipe the head of the spirit went into a great cloud, and the whole surface of the rock in a radius of several miles was melted and glazed. The legend, with others which, according to early records, have been treasured by the Indians, was taken by Longfellow to form the first picture in his Hiawatha.

Silliman's Journal of Science (Vol. XXXVII, page 394,) gives an analysis of Red Pipestone. It is pronounced to be a mineral compound (and not steatite), is harder than gypsum, and softer than carbonate of lime. Specimens bear as high a luster and polish as melted glass.

It may be of interest to the reader to know more of the ends sought by these treaties, also more concerning the contracting parties. In separate treaties, all of the same tenor and made in October, 1865, with various tribes of Sioux, those Indians promised to be very good and to maintain peaceful relations with the whites. In consideration therefor the U. S. Government promised to pay to each family or lodge the sum of $25.00, payable annually for a stated period, also to distribute to the widow and the seventeen children of Ish-tah-cha-ne-aha the sum of five hundred dollars, said friendly chief having been slain by U. S. soldiers.

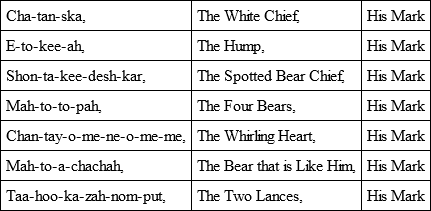

To one of these instruments were affixed the signatures of the following eminent warriors, whose names are given in the form in which they appeared on one of the documents, – the translation also being written as shown.

There were also attached fourteen other names with the signatures of the Commissioners of the United States.

In April and May, 1868, treaties were finally concluded at Fort Laramie with the Brule, Ogallala, and other Sioux, also the Arapahoes and Crows, and were signed by scores of their chiefs and head men; General W. T. Sherman, also Generals Harvey, Terry, and Auger acting on behalf of the U. S. Government.

CHAPTER XV

Red Cloud on the War Path

THE statement that a satisfactory treaty had been concluded with the Indians was communicated to the various parties of travelers who were camped near the post. There being a sufficient number of armed men and wagons to conform to the rules of the War Department, ready to proceed westward, we were ordered to move on.

But where was the great chief, Red Cloud, and his savage warriors who, enraged because of the precipitate advance of the U. S. troops into the very territory that was under consideration at the council, had struck out westward with the avowed purpose of defending it against all comers? What were the experiences of the hundreds of men, women, and soldiers who in that fateful season were traversing those Wyoming trails?

A recital of incidents that occurred during the treaty, if not followed by some reference to succeeding events would, figuratively speaking, leave the reader high in the air. On examining the letters and messages of the Presidents, I find revealed therein the astonishing fact that even our chief executive was long in ignorance of the true situation of Indian affairs in Wyoming. It would, therefore, not be strange if readers generally were also uninformed upon the subject. In his Annual Message, dated December 3, 1866, President Johnson, referring to this Laramie treaty, informs Congress that a treaty had been concluded with the Indians, "who," (as the message states) "enticed into armed opposition to our Government at the outbreak of the Rebellion, have unconditionally submitted to our authority, and manifested an earnest desire for a renewal of friendly relations." For the whole period of nearly five months prior to the date of the message above cited the Indian war was going on; and within three days of the date of the message there occurred in Wyoming, under Red Cloud, one of the most appalling Indian massacres that has darkened the history of our country.

In his message of the following year, the President was sufficiently advised to report "barbarous violence which, instigated by real or imaginary grievance, the Indians have committed upon emigrants and frontier settlements," but he makes no allusion to an entire detachment of our brave soldiers, every one of whom was slaughtered in one day. He urges that "the moral and intellectual improvement of the Indians can be most effectually secured by concentrating them upon portions of the country set apart for their exclusive use, and located at points remote from our highways and encroaching white settlements."

Could any proposition be made better calculated to fire the blood of a savage Chief, whose people had been driven year by year until they had reached the last fastness? How large would be the "point" recommended in the message, upon which these migratory tribes should be settled? Where was there remaining an unoccupied portion of our country that might not become a highway as quickly as has the remote territory then in controversy? Experience had taught the Red Men that none of their grounds, wherever they might be, were secure to them. Many of the Sioux, who had been slowly driven back upon other tribes with whom they had often been at war, appear to have shared a joint possession of the Powder River country, where game was abundant. The "moral and intellectual advancement" recommended in the President's message probably did not concern them so much as did the question of food in the long winters.

While it is recognized that barbarism must give way to the march of civilization, it is humiliating to review the heartless disregard of the principles of equity and square dealing, of which some of the representatives of our nation have been guilty in our relations with these great tribes. The general situation as it existed during the few weeks following this treaty is tersely described in the report of a special commission chosen by the United States Senate to investigate the Fetterman massacre already referred to. The commission convened at Fort McPherson in April, 1867, and after thirty days' investigation made its report, which concluded with the following summary:

"We, therefore, report that all the Sioux Indians occupying the country about Fort Phil Kearney have been in a state of war against the whites since the 20th day of June, 1866, and that they have waged and carried on this war for the purpose of defending their ancient possessions from invasion and occupation by the whites.

"The war has been carried on by the Indians with most extraordinary vigor and unwonted success.

"During the time from July 26th, the day on which Lieutenant Wand's train was attacked, to the 21st of December, on which Lieutenant Colonel Fetterman with his command of eighty officers and men were overpowered and massacred, they (the Indians) killed ninety-one enlisted men and five officers of our army, and killed fifty-eight citizens, and wounded twenty more, and captured and drove away three hundred and six oxen and cows, three hundred and four mules, and one hundred and sixty-one horses. During this time they appeared in front of Fort Phil Kearney making hostile demonstrations and committing hostile acts fifty-one different times, and attacked nearly every train and person that attempted to pass over the Montana road." The figures in the foregoing report do not include the great loss of human life and of live stock and other property that occurred in connection with the massacre in December.

It was early in this period that the scoundrels at Fort Laramie, who should have known better, assured us and other travelers less fortunate than we were, that it would be quite safe for emigrants to proceed. It may be asked what motive could inspire these roseate but unreliable reports. The answer is simple when one becomes somewhat familiar with the type of many of the men who on the part of the Government conducted these highly important negotiations; and when one realizes the additional fact that the opportunity for personal profit overshadowed everything, while the dignity of the Government and the principles of equity were disregarded.

In the second volume of his Forty Years a Fur Trader, Larpenteur devotes an entire chapter to a sketch of the many Indian agents with whom he was familiar who served the Government as "the fathers of the Indians" during those many years. The majority of those whose names he gives are stated by him to be "drunken gamblers." "Some were interested in the fur trade" and therefore were using the great authority of the United States Government to further their personal ends. "Some were ignorant beaver trappers," but not one of them, according to Larpenteur's reports, seems to have possessed those qualifications which would make for "the moral and intellectual advancement" of the wards of the nation so prominently urged in the President's message. In fact, the Indian agent should be a man of probity instead of a man whom the Indians openly declared to be a liar, and certainly he should not influence an agreement for the profit of the post sutler, who has the exclusive trading privilege at the post.

We were in the atmosphere of events and at every available opportunity conferred with officers, soldiers, and non-combatants, gleaning all possible information concerning passing incidents, and followed those observations with later investigations, so that we could not but believe that we became fairly well informed concerning the Indian history of the few weeks following Red Cloud's withdrawal from Laramie. For much valuable information I am under obligations to General Carrington, who was then in command in Wyoming, and who has given me data not easily obtained from any other original and trustworthy source. A record of the many thrilling events that rapidly followed each other would fill a volume and is for the historian to compile. Coutant has well described them, but the final dramatic conflict that crushed the Indian uprising and opened the path for emigration demands a passing glance.