полная версия

полная версияAudubon and his Journals, Volume 2 (of 2)

Mr. Denig gave me the following "Bear Story," as he heard it from the parties concerned: "In the year 1835 two men set out from a trading-post at the head of the Cheyenne, and in the neighborhood of the Black Hills, to trap Beaver; their names were Michel Carrière and Bernard Le Brun. Carrière was a man about seventy years old, and had passed most of his life in the Indian country, in this dangerous occupation of trapping. One evening as they were setting their traps along the banks of a stream tributary to the Cheyenne, somewhat wooded by bushes and cottonwood trees, their ears were suddenly saluted by a growl, and in a moment a large she Bear rushed upon them. Le Brun, being a young and active man, immediately picked up his gun, and shot the Bear through the bowels. Carrière also fired, but missed. The Bear then pursued them, but as they ran for their lives, their legs did them good service; they escaped through the bushes, and the Bear lost sight of them. They had concluded the Bear had given up the chase, and were again engaged in setting their traps, when Carrière, who was a short distance from Le Brun, went through a small thicket with a trap and came directly in front of the huge, wounded beast, which, with one spring, bounded upon him and tore him in an awful manner. With one stroke of the paw on his face and forehead he cut his nose in two, and one of the claws reached inward nearly to the brain at the root of the nose; the same stroke tore out his right eye and most of the flesh from that side of his face. His arm and side were literally torn to pieces, and the Bear, after handling him in this gentle manner for two or three minutes, threw him upwards about six feet, when he lodged, to all appearance dead, in the fork of a tree. Le Brun, hearing the noise, ran to his assistance, and again shot the Bear and killed it. He then brought what he at first thought was the dead body of his friend to the ground. Little appearance of a human being was left to the poor man, but Le Brun found life was not wholly extinct. He made a travaille and carried him by short stages to the nearest trading-post, where the wounded man slowly recovered, but was, of course, the most mutilated-looking being imaginable. Carrière, in telling the story, says that he fully believes it to have been the Holy Virgin that lifted him up and placed him in the fork of the tree, and thus preserved his life. The Bear is stated to have been as large as a common ox, and must have weighed, therefore, not far from 1500 lbs." Mr. Denig adds that he saw the man about a year after the accident, and some of the wounds were, even then, not healed. Carrière fully recovered, however, lived a few years, and was killed by the Blackfeet near Fort Union.

When Bell was fixing his traps on his horse this morning, I was amused to see Provost and La Fleur laughing outright at him, as he first put on a Buffalo robe under his saddle, a blanket over it, and over that his mosquito bar and his rain protector. These old hunters could not understand why he needed all these things to be comfortable; then, besides, he took a sack of ship-biscuit. Provost took only an old blanket, a few pounds of dried meat, and his tin cup, and rode off in his shirt and dirty breeches. La Fleur was worse off still, for he took no blanket, and said he could borrow Provost's tin cup; but he, being a most temperate man, carried the bottle of whiskey to mix with the brackish water found in the Mauvaises Terres, among which they have to travel till their return. Harris and I contemplated going to a quarry from which the stones of the powder magazine were brought, but it became too late for us to start in time to see much, and the wrong horses were brought us, being both runners; we went, however, across the river after Rabbits. Harris killed a Red-cheeked Woodpecker and shot at a Rabbit, which he missed. We had a sort of show by Moncrévier which was funny, and well performed; he has much versatility, great powers of mimicry, and is a far better actor than many who have made names for themselves in that line. Jean Baptiste told me the following: "About twelve years ago when Mr. McKenzie was the superintendent of this fort, at the season when green peas were plenty and good, Baptiste was sent to the garden about half a mile off, to gather a quantity. He was occupied doing this, when, at the end of a row, to his astonishment, he saw a very large Bear gathering peas also. Baptiste dropped his tin bucket, ran back to the fort as fast as possible, and told Mr. McKenzie, who immediately summoned several other men with guns; they mounted their horses, rode off, and killed the Bear; but, alas! Mr. Bruin had emptied the bucket of peas."

August 8, Tuesday. Another sultry day. Immediately after breakfast Mr. Larpenteur drove Harris and myself in search of geological specimens, but we found none worth having. We killed a Spermophilus hoodii, which, although fatally wounded, entered its hole, and Harris had to draw it out by the hind legs. We saw a family of Rock Wrens, and killed four of them. I killed two at one shot; one of the others must have gone in a hole, for though we saw it fall we could not find it. Another, after being shot, found its way under a flat stone, and was there picked up, quite dead, Mr. Larpenteur accidentally turning the stone up. We saw signs of Antelopes and of Hares (Townsend), and rolled a large rock from the top of a high hill. The notes of the Rock Wren are a prolonged cree-è-è-è. On our return home we heard that Boucherville and his five hunters had returned with nothing for me, and they had not met Bell and his companions. We were told also that a few minutes after our departure the roarings and bellowings of Buffalo were heard across the river, and that Owen and two men had been despatched with a cart to kill three fat cows but no more; so my remonstrances about useless slaughter have not been wholly unheeded. Harris was sorry he had missed going, and so was I, as both of us could have done so. The milk of the Buffalo cow is truly good and finely tasted, but the bag is never large as in our common cattle, and this is probably a provision of nature to render the cows more capable to run off, and escape from their pursuers. Bell, Provost, and La Fleur returned just before dinner; they had seen no Bighorns, and only brought the flesh of two Deer killed by La Fleur, and a young Magpie. This afternoon Provost skinned a calf that was found by one of the cows that Owen killed; it was very young, only a few hours old, but large, and I have taken its measurements. It is looked upon as a phenomenon, as no Buffalo cow calves at this season. The calving time is from about the 1st of February to the last of May. Owen went six miles from the fort before he saw the cattle; there were more than three hundred in number, and Harris and I regretted the more we had not gone, but had been fruitlessly hunting for stones. It is curious that while Harris was searching for Rabbits early this morning, he heard the bellowing of the bulls, and thought first it was the growling of a Grizzly Bear, and then that it was the fort bulls, so he mentioned it to no one. To-morrow evening La Fleur and two men will go after Bighorns again, and they are not to return before they have killed one male, at least. This evening we went a-fishing across the river, and caught ten good catfish of the upper Missouri species, the sweetest and best fish of the sort that I have eaten in any part of the country. Our boat is going on well, and looks pretty to boot. Her name will be the "Union," in consequence of the united exertions of my companions to do all that could be done, on this costly expedition. The young Buffaloes now about the fort have begun shedding their red coats, the latter-colored hair dropping off in patches about the size of the palm of my hand, and the new hair is dark brownish black.

August 9, Wednesday. The weather is cool and we are looking for rain. Squires, Provost, and La Fleur went off this morning after an early breakfast, across the river for Bighorns with orders not to return without some of these wild animals, which reside in the most inaccessible portions of the broken and lofty clay hills and stones that exist in this region of the country; they never resort to the low lands except when moving from one spot to another; they swim rivers well, as do Antelopes. I have scarcely done anything but write this day, and my memorandum books are now crowded with sketches, measurements, and descriptions. We have nine Indians, all Assiniboins, among whom five are chiefs. These nine Indians fed for three days on the flesh of only a single Swan; they saw no Buffaloes, though they report large herds about their village, fully two hundred miles from here. This evening I caught about one dozen catfish, and shot a Spermophilus hoodii, an old female, which had her pouches distended and filled with the seeds of the wild sunflower of this region. I am going to follow one of their holes and describe the same.

August 10, Thursday. Bell and I took a walk after Rabbits, but saw none. The nine Indians, having received their presents, went off with apparent reluctance, for when you begin to give them, the more they seem to demand. The horseguards brought in another Spermophilus hoodii; after dinner we are going to examine one of their burrows. We have been, and have returned; the three burrows which we dug were as follows: straight downward for three or four inches, and gradually becoming deeper in an oblique slant, to the depth of eight or nine inches, but not more, and none of these holes extended more than six or seven feet beyond this. I was disappointed at not finding nests, or rooms for stores. Although I have said much about Buffalo running, and butchering in general, I have not given the particular manner in which the latter is performed by the hunters of this country, – I mean the white hunters, – and I will now try to do so. The moment that the Buffalo is dead, three or four hunters, their faces and hands often covered with gunpowder, and with pipes lighted, place the animal on its belly, and by drawing out each fore and hind leg, fix the body so that it cannot fall down again; an incision is made near the root of the tail, immediately above the root in fact, and the skin cut to the neck, and taken off in the roughest manner imaginable, downwards and on both sides at the same time. The knives are going in all directions, and many wounds occur to the hands and fingers, but are rarely attended to at this time. The pipe of one man has perhaps given out, and with his bloody hands he takes the one of his nearest companion, who has his own hands equally bloody. Now one breaks in the skull of the bull, and with bloody fingers draws out the hot brains and swallows them with peculiar zest; another has now reached the liver, and is gobbling down enormous pieces of it; whilst, perhaps, a third, who has come to the paunch, is feeding luxuriously on some – to me – disgusting-looking offal. But the main business proceeds. The flesh is taken off from the sides of the boss, or hump bones, from where these bones begin to the very neck, and the hump itself is thus destroyed. The hunters give the name of "hump" to the mere bones when slightly covered by flesh; and it is cooked, and very good when fat, young, and well broiled. The pieces of flesh taken from the sides of these bones are called filets, and are the best portion of the animal when properly cooked. The fore-quarters, or shoulders, are taken off, as well as the hind ones, and the sides, covered by a thin portion of flesh called the depouille, are taken out. Then the ribs are broken off at the vertebræ, as well as the boss bones. The marrow-bones, which are those of the fore and hind legs only, are cut out last. The feet usually remain attached to these; the paunch is stripped of its covering of layers of fat, the head and the backbone are left to the Wolves, the pipes are all emptied, the hands, faces, and clothes all bloody, and now a glass of grog is often enjoyed, as the stripping off the skins and flesh of three or four animals is truly very hard work. In some cases when no water was near, our supper was cooked without our being washed, and it was not until we had travelled several miles the next morning that we had any opportunity of cleaning ourselves; and yet, despite everything, we are all hungry, eat heartily, and sleep soundly. When the wind is high and the Buffaloes run towards it, the hunter's guns very often snap, and it is during their exertions to replenish their pans, that the powder flies and sticks to the moisture every moment accumulating on their faces; but nothing stops these daring and usually powerful men, who the moment the chase is ended, leap from their horses, let them graze, and begin their butcher-like work.

August 11, Friday. The weather has been cold and windy, and the day has passed in comparative idleness with me. Squires returned this afternoon alone, having left Provost and La Fleur behind. They have seen only two Bighorns, a female and her young. It was concluded that, if our boat was finished by Tuesday next, we would leave on Wednesday morning, but I am by no means assured of this, and Harris was quite startled at the very idea. Our boat, though forty feet long, is, I fear, too small. Nous verrons! Some few preparations for packing have been made, but Owen, Harris, and Bell are going out early to-morrow morning to hunt Buffaloes, and when they return we will talk matters over. The activity of Buffaloes is almost beyond belief; they can climb the steep defiles of the Mauvaises Terres in hundreds of places where men cannot follow them, and it is a fine sight to see a large gang of them proceeding along these defiles four or five hundred feet above the level of the bottoms, and from which pathway if one of the number makes a mis-step or accidentally slips, he goes down rolling over and over, and breaks his neck ere the level ground is reached. Bell and Owen saw a bull about three years old that leaped a ravine filled with mud and water, at least twenty feet wide; it reached the middle at the first bound, and at the second was mounted on the opposite bank, from which it kept on bounding, till it gained the top of quite a high hill. Mr. Culbertson tells me that these animals can endure hunger in a most extraordinary manner. He says that a large bull was seen on a spot half way down a precipice, where it had slid, and from which it could not climb upwards, and either could not or would not descend; at any rate, it did not leave the position in which it found itself. The party who saw it returned to the fort, and, on their way back on the twenty-fifth day after, they passed the hill, and saw the bull standing there. The thing that troubles them most is crossing rivers on the ice; their hoofs slip from side to side, they become frightened, and stretch their four legs apart to support the body, and in such situations the Indians and white hunters easily approach, and stab them to the heart, or cut the hamstrings, when they become an easy prey. When in large gangs those in the centre are supported by those on the outposts, and if the stream is not large, reach the shore and readily escape. Indians of different tribes hunt the Buffalo in different ways; some hunt on horseback, and use arrows altogether; they are rarely expert in reloading the gun in the close race. Others hunt on foot, using guns, arrows, or both. Others follow with patient perseverance, and kill them also. But I will give you the manner pursued by the Mandans. Twenty to fifty men start, as the occasion suits, each provided with two horses, one of which is a pack-horse, the other fit for the chase. They have quivers with from twenty to fifty arrows, according to the wealth of the hunter. They ride the pack horse bareback, and travel on, till they see the game, when they leave the pack-horse, and leap on the hunter, and start at full speed and soon find themselves amid the Buffaloes, on the flanks of the herd, and on both sides. When within a few yards the arrow is sent, they shoot at a Buffalo somewhat ahead of them, and send the arrow in an oblique manner, so as to pass through the lights. If the blood rushes out of the nose and mouth the animal is fatally wounded, and they shoot at it no more; if not, a second, and perhaps a third arrow, is sent before this happens. The Buffaloes on starting carry the tail close in between the legs, but when wounded they switch it about, especially if they wish to fight, and then the hunter's horse shies off and lets the mad animal breathe awhile. If shot through the heart, they occasionally fall dead on the instant; sometimes, if not hit in the right place, a dozen arrows will not stop them. When wounded and mad they turn suddenly round upon the hunter, and rush upon him in such a quick and furious manner that if horse and rider are not both on the alert, the former is overtaken, hooked and overthrown, the hunter pitched off, trampled and gored to death. Although the Buffalo is such a large animal, and to all appearance a clumsy one, it can turn with the quickness of thought, and when once enraged, will rarely give up the chase until avenged for the wound it has received. If, however, the hunter is expert, and the horse fleet, they outrun the bull, and it returns to the herd. Usually the greater number of the gang is killed, but it very rarely happens that some of them do not escape. This however is not the case when the animal is pounded, especially by the Gros Ventres, Black Feet, and Assiniboins. These pounds are called "parks," and the Buffaloes are made to enter them in the following manner: The park is sometimes round and sometimes square, this depending much on the ground where it is put up; at the end of the park is what is called a precipice of some fifteen feet or less, as may be found. It is approached by a funnel-shaped passage, which like the park itself is strongly built of logs, brushwood, and pickets, and when all is ready a young man, very swift of foot, starts at daylight covered over with a Buffalo robe and wearing a Buffalo head-dress. The moment he sees the herd to be taken, he bellows like a young calf, and makes his way slowly towards the contracted part of the funnel, imitating the cry of the calf, at frequent intervals. The Buffaloes advance after the decoy; about a dozen mounted hunters are yelling and galloping behind them, and along both flanks of the herd, forcing them by these means to enter the mouth of the funnel. Women and children are placed behind the fences of the funnel to frighten the cattle, and as soon as the young man who acts as decoy feels assured that the game is in a fair way to follow to the bank or "precipice," he runs or leaps down the bank, over the barricade, and either rests, or joins in the fray. The poor Buffaloes, usually headed by a large bull, proceed, leap down the bank in haste and confusion, the Indians all yelling and pursuing till every bull, cow, and calf is impounded. Although this is done at all seasons, it is more general in October or November, when the hides are good and salable. Now the warriors are all assembled by the pen, calumets are lighted, and the chief smokes to the Great Spirit, the four points of the compass, and lastly to the Buffaloes. The pipe is passed from mouth to mouth in succession, and as soon as this ceremony is ended, the destruction commences. Guns shoot, arrows fly in all directions, and the hunters being on the outside of the enclosure, destroy the whole gang, before they jump over to clean and skin the murdered herd. Even the children shoot small, short arrows to assist in the destruction. It happens sometimes however, that the leader of the herd will be restless at the sight of the precipices, and if the fence is weak will break through it, and all his fellows follow him, and escape. The same thing sometimes takes place in the pen, for so full does this become occasionally that the animals touch each other, and as they cannot move, the very weight against the fence of the pen is quite enough to break it through; the smallest aperture is sufficient, for in a few minutes it becomes wide, and all the beasts are seen scampering over the prairies, leaving the poor Indians starving and discomfited. Mr. Kipp told me that while travelling from Lake Travers to the Mandans, in the month of August, he rode in a heavily laden cart for six successive days through masses of Buffaloes, which divided for the cart, allowing it to pass without opposition. He has seen the immense prairie back of Fort Clark look black to the tops of the hills, though the ground was covered with snow, so crowded was it with these animals; and the masses probably extended much further. In fact it is impossible to describe or even conceive the vast multitudes of these animals that exist even now, and feed on these ocean-like prairies.

August 12, Saturday. Harris, Bell, and Owen went after Buffaloes; killed six cows and brought them home. Weather cloudy, and rainy at times. Provost returned with La Fleur this afternoon, had nothing, but had seen a Grizzly Bear. The "Union" was launched this evening and packing, etc., is going on. I gave a memorandum to Jean Baptiste Moncrévier of the animals I wish him to procure for me.

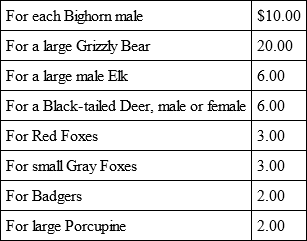

August 13, Sunday. A most beautiful day. About dinner time I had a young Badger brought to me dead; I bought it, and gave in payment two pounds of sugar. The body of these animals is broader than high, the neck is powerfully strong, as well as the fore-arms, and strongly clawed fore-feet. It weighed 8½ lbs. Its measurements were all taken. When the pursuer gets between a Badger and its hole, the animal's hair rises, and it at once shows fight. A half-breed hunter told Provost, who has just returned from Fort Mortimer, that he was anxious to go down the river with me, but I know the man and hardly care to have him. If I decide to take him Mr. Culbertson, to whom I spoke of the matter, told me my only plan was to pay him by the piece for what he killed and brought on board, and that in case he did not turn out well between this place and Fort Clark, to leave him there; so I have sent word to him to this effect by Provost this afternoon. Bell is skinning the Badger, Sprague finishing the map of the river made by Squires, and the latter is writing. The half-breed has been here, and the following is our agreement: "It is understood that François Détaillé will go with me, John J. Audubon, and to secure for me the following quadrupeds – if possible – for which he will receive the prices here mentioned, payable at Fort Union, Fort Clark, or Fort Pierre, as may best suit him.

Independent of which I agree to furnish him with his passage and food, he to work as a hand on board. Whatever he kills for food will be settled when he leaves us, or, as he says, when he meets the Opposition boat coming up to Fort Mortimer." He will also accompany us in our hunt after Bighorns, which I shall undertake, notwithstanding Mr. Culbertson and Squires, who have been to the Mauvaises Terres, both try to dissuade me from what they fear will prove over-fatiguing; but though my strength is not what it was twenty years ago, I am yet equal to much, and my eyesight far keener than that of many a younger man, though that too tells me I am no longer a youth…

The only idea I can give in writing of what are called the "Mauvaises Terres" would be to place some thousands of loaves of sugar of different sizes, from quite small and low, to large and high, all irregularly truncated at top, and placed somewhat apart from each other. No one who has not seen these places can form any idea of these resorts of the Rocky Mountain Rams, or the difficulty of approaching them, putting aside their extreme wildness and their marvellous activity. They form paths around these broken-headed cones (that are from three to fifteen hundred feet high), and run round them at full speed on a track that, to the eye of the hunter, does not appear to be more than a few inches wide, but which is, in fact, from a foot to eighteen inches in width. In some places there are piles of earth from eight to ten feet high, or even more, the tops of which form platforms of a hard and shelly rocky substance, where the Bighorn is often seen looking on the hunter far below, and standing immovable, as if a statue. No one can imagine how they reach these places, and that too with their young, even when the latter are quite small. Hunters say that the young are usually born in such places, the mothers going there to save the helpless little one from the Wolves, which, after men, seem to be their greatest destroyers. The Mauvaises Terres are mostly formed of grayish white clay, very sparsely covered with small patches of thin grass, on which the Bighorns feed, but which, to all appearance, is a very scanty supply, and there, and there only, they feed, as not one has ever been seen on the bottom or prairie land further than the foot of these most extraordinary hills. In wet weather, no man can climb any of them, and at such times they are greasy, muddy, sliding grounds. Oftentimes when a Bighorn is seen on a hill-top, the hunter has to ramble about for three or four miles before he can approach within gunshot of the game, and if the Bighorn ever sees his enemy, pursuit is useless. The tops of some of these hills, and in some cases whole hills about thirty feet high, are composed of a conglomerated mass of stones, sand, and clay, with earth of various sorts, fused together, and having a brick-like appearance. In this mass pumice-stone of various shapes and sizes is to be found. The whole is evidently the effect of volcanic action. The bases of some of these hills cover an area of twenty acres or more, and the hills rise to the height of three or four hundred feet, sometimes even to eight hundred or a thousand; so high can the hunter ascend that the surrounding country is far, far beneath him. The strata are of different colored clays, coal, etc., and an earth impregnated with a salt which appears to have been formed by internal fire or heat, the earth or stones of which I have first spoken in this account, lava, sulphur, salts of various kinds, oxides and sulphates of iron; and in the sand at the tops of some of the highest hills I have found marine shells, but so soft and crumbling as to fall apart the instant they were exposed to the air. I spent some time over various lumps of sand, hoping to find some perfect ones that would be hard enough to carry back to St. Louis; but 't was "love's labor lost," and I regretted exceedingly that only a few fragments could be gathered. I found globular and oval shaped stones, very heavy, apparently composed mostly of iron, weighing from fifteen to twenty pounds; numbers of petrified stumps from one to three feet in diameter; the Mauvaises Terres abound with them; they are to be found in all parts from the valleys to the tops of the hills, and appear to be principally of cedar. On the sides of the hills, at various heights, are shelves of rock or stone projecting out from two to six, eight, or even ten feet, and generally square, or nearly so; these are the favorite resorts of the Bighorns during the heat of the day, and either here or on the tops of the highest hills they are to be found. Between the hills there is generally quite a growth of cedar, but mostly stunted and crowded close together, with very large stumps, and between the stumps quite a good display of grass; on the summits, in some few places, there are table-lands, varying from an area of one to ten or fifteen acres; these are covered with a short, dry, wiry grass, and immense quantities of flat leaved cactus, the spines of which often warn the hunter of their proximity, and the hostility existing between them and his feet. These plains are not more easily travelled than the hillsides, as every step may lead the hunter into a bed of these pests of the prairies. In the valleys between the hills are ravines, some of which are not more than ten or fifteen feet wide, while their depth is beyond the reach of the eye. Others vary in depth from ten to fifty feet, while some make one giddy to look in; they are also of various widths, the widest perhaps a hundred feet. The edges, at times, are lined with bushes, mostly wild cherry; occasionally Buffaloes make paths across them, but this is rare. The only safe way to pass is to follow the ravine to the head, which is usually at the foot of some hill, and go round. These ravines are mostly between every two hills, although like every general rule there are variations and occasionally places where three or more hills make only one ravine. These small ravines all connect with some larger one, the size of which is in proportion to its tributaries. The large one runs to the river, or the water is carried off by a subterranean channel. In these valleys, and sometimes on the tops of the hills, are holes, called "sink holes;" these are formed by the water running in a small hole and working away the earth beneath the surface, leaving a crust incapable of supporting the weight of a man; and if an unfortunate steps on this crust, he soon finds himself in rather an unpleasant predicament. This is one of the dangers that attend the hunter in these lands; these holes eventually form a ravine such as I have before spoken of. Through these hills it is almost impossible to travel with a horse, though it is sometimes done by careful management, and a correct knowledge of the country. The sides of the hills are very steep, covered with the earth and stones of which I have spoken, all of which are quite loose on the surface; occasionally a bunch of wormwood here and there seems to assist the daring hunter; for it is no light task to follow the Bighorns through these lands, and the pursuit is attended with much danger, as the least slip at times would send one headlong into the ravines below. On the sides of these high hills the water has washed away the earth, leaving caves of various sizes; and, in fact, in some places all manner of fantastic forms are made by the same process. Occasionally in the valleys are found isolated cones or domes, destitute of vegetation, naked and barren. Throughout the Mauvaises Terres there are springs of water impregnated with salt, sulphur, magnesia, and many other salts of all kinds. Such is the water the hunter is compelled to drink, and were it not that it is as cold as ice it would be almost impossible to swallow it. As it is, many of these waters operate as cathartics or emetics; this is one of the most disagreeable attendants of hunting in these lands. Moreover, venomous snakes of many kinds are also found here. I saw myself only one copperhead, and a common garter-snake. Notwithstanding the rough nature of the country, the Buffaloes have paths running in all directions, and leading from the prairies to the river. The hunter sometimes, after toiling for an hour or two up the side of one of these hills, trying to reach the top in hopes that when there he will have for a short distance at least, either a level place or good path to walk on, finds to his disappointment that he has secured a point that only affords a place scarcely large enough to stand on, and he has the trouble of descending, perhaps to renew his disappointment in the same way, again and again, such is the deceptive character of the country. I was thus deceived time and again, while in search of Bighorns. If the hill does not terminate in a point it is connected with another hill, by a ridge so narrow that nothing but a Bighorn can walk on it. This is the country that the Mountain Ram inhabits, and if, from this imperfect description, any information can be derived, I shall be more than repaid for the trouble I have had in these tiresome hills. Whether my theory be correct or incorrect, it is this: These hills were at first composed of the clays that I have mentioned, mingled with an immense quantity of combustible material, such as coal, sulphur, bitumen, etc.; these have been destroyed by fire, or (at least the greater part) by volcanic action, as to this day, on the Black Hills and in the hills near where I have been, fire still exists; and from the immense quantities of pumice-stone and melted ores found among the hills, even were there no fire now to be seen, no one could doubt that it had, at some date or other, been there; as soon as this process had ceased, the rains washed out the loose material, and carried it to the rivers, leaving the more solid parts as we now find them; the action of water to this day continues. As I have said, the Bighorns are very fond of resorting to the shelves, or ledges, on the sides of the hills, during the heat of the day, when these places are shaded; here they lie, but are aroused instantly upon the least appearance of danger, and, as soon as they have discovered the cause of alarm, away they go, over hill and ravine, occasionally stopping to look round, and when ascending the steepest hill, there is no apparent diminution of their speed. They will ascend and descend places, when thus alarmed, so inaccessible that it is almost impossible to conceive how, and where, they find a foothold. When observed before they see the hunter, or while they are looking about when first alarmed, are the only opportunities the hunter has to shoot them; for, as soon as they start there is no hope, as to follow and find them is a task not easily accomplished, for where or how far they go when thus on the alert, heaven only knows, as but few hunters have ever attempted a chase. At all times they have to be approached with the greatest caution, as the least thing renders them on the qui vive. When not found on these shelves, they are seen on the tops of the most inaccessible and highest hills, looking down on the hunters, apparently conscious of their security, or else lying down tranquilly in some sunny spot quite out of reach. As I have observed before, the only times that these animals can be shot are when on these ledges, or when moving from one point to another. Sometimes they move only a few hundred yards, but it will take the hunter several hours to approach near enough for a shot, so long are the détours he is compelled to make. I have been thus baffled two or three times. The less difficult hills are found cut up by paths made by these animals; these are generally about eighteen inches wide. These animals appear to be quite as agile as the European Chamois, leaping down precipices, across ravines, and running up and down almost perpendicular hills. The only places I could find that seemed to afford food for them, was between the cedars, as I have before mentioned; but the places where they are most frequently found are barren, and without the least vestige of vegetation. From the character of the lands where these animals are found, their own shyness, watchfulness, and agility, it is readily seen what the hunter must endure, and what difficulties he must undergo to near these "Wild Goats." It is one constant time of toil, anxiety, fatigue, and danger. Such the country! Such the animal! Such the hunting!