Полная версия

Who Could That Be at This Hour?

EGMONT

Who Could That Be at This Hour? First published in Great Britain 2012 by Egmont UK Limited The Yellow Building 1 Nicholas Road London W11 4AN

Text copyright © 2012 Lemony Snicket Art copyright © 2012 Seth

ALL THE WRONG QUESTIONS: Who Could That Be at This Hour? by Lemony Snicket reprinted by arrangement with Charlotte Sheedy Literary Agency.

Art by Seth reprinted by arrangement with Little, Brown and Company Hachette Book Group / 237 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017.

The moral rights of the author and artist have been asserted.

978 1 4052 5621 6 978 1 7803 1130 2 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Printed and bound in Italy

47911/1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher and copyright owner.

EGMONT LUCKY COIN

Our story began over a century ago, when seventeen-year-old Egmont Harald Petersen found a coin in the street.

He was on his way to buy a flyswatter, a small hand-operated printing machine that he then set up in his tiny apartment.

The coin brought him such good luck that today Egmont has offices in over 30 countries around the world. And that lucky coin is still kept at the company’s head offices in Denmark.

TO: Walleye

FROM: LS

FILE UNDER: Stain’d-by-the-Sea,

accounts of; theft, investigations of; Hangfire; hawsers; ink;

double-crossings; et cetera

1/4

cc: VFDhq

CHAPTER ONE

There was a town, and there was a girl, and there was a theft. I was living in the town, and I was hired to investigate the theft, and I thought the girl had nothing to do with it. I was almost thirteen and I was wrong. I was wrong about all of it. I should have asked the question “Why would someone say something was stolen when it was never theirs to begin with?” Instead, I asked the wrong question—four wrong questions, more or less. This is the account of the first.

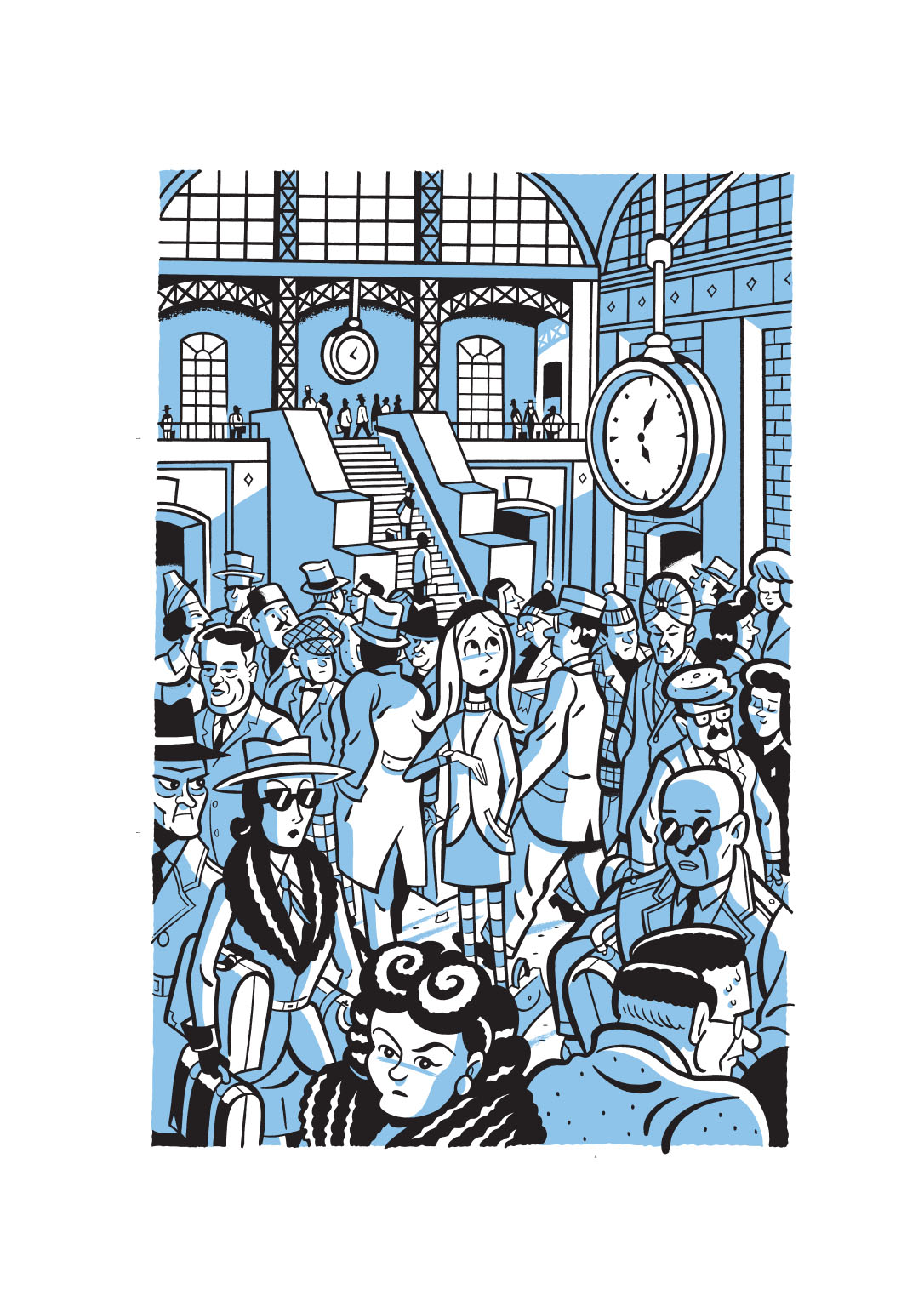

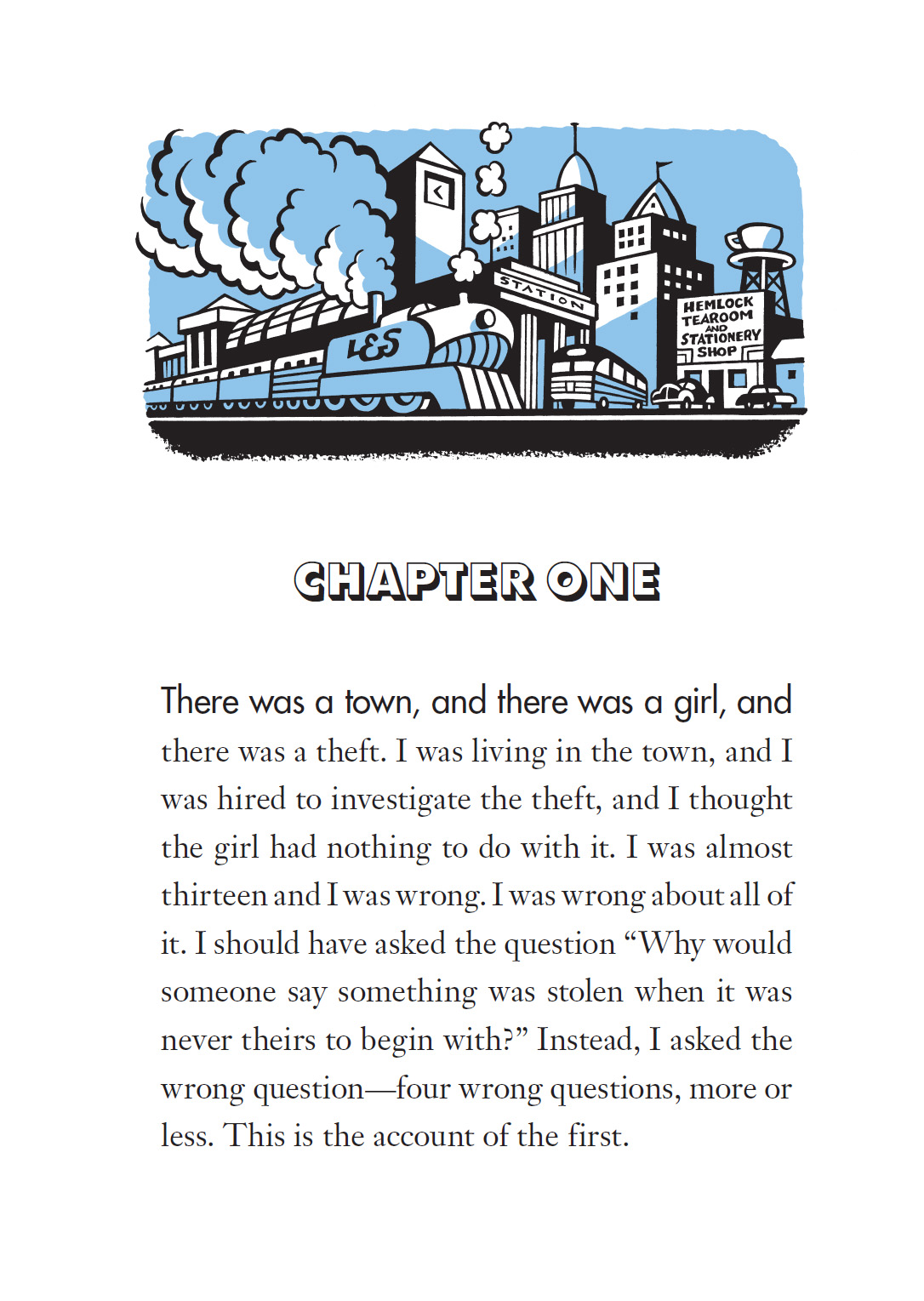

The Hemlock Tearoom and Stationery Shop is the sort of place where the floors always feel dirty, even when they are clean. They were not clean on the day in question. The food at the Hemlock is too awful to eat, particularly the eggs, which are probably the worst eggs in the entire city, including those on exhibit at

the Museum of Bad Breakfast, where visitors can learn just how badly eggs can be prepared. The Hemlock sells paper and pens that are damaged and useless, but the tea is drinkable, and the place is located across the street from the train station, so it is an acceptable place to sit with one’s parents before boarding a train for a new life. I was wearing the suit I’d been given as a graduation present. It had hung in my closet for weeks, like an empty person. I felt glum and thirsty. When the tea arrived, for a moment the steam was all I could see. I’d said good-bye to someone very quickly and was wishing I’d taken longer. I told myself that

it didn’t matter and that certainly it was no time to frown around town. You have work to do, Snicket, I told myself. There is no time for moping.

You’ll see her soon enough in any case, I thought, incorrectly.

Then the steam cleared, and I looked at the people who were with me. It is curious to look at one’s family and try to imagine how they look to strangers. I saw a large-shouldered man in a brown, linty suit that looked like it made him uncomfortable, and a woman drumming her fingernails on the table, over and over, the sound like a tiny horse’s galloping. She happened to have a flower in her hair. They were both smiling, particularly the man.

“You have plenty of time before your train, son,” he said. “Would you like to order something to eat? Eggs?”

“No, thank you,” I said.

“We’re both so proud of our little boy,” said

the woman, who perhaps would have looked nervous to someone who was looking closely at her. Or perhaps not. She stopped drumming her fingers on the table and ran them through my hair. Soon I would need a haircut. “You must be all a-tingle with excitement.”

“I guess so,” I said, but I did not feel a-tingle. I did not feel a-anything.

“Put your napkin in your lap,” she told me.

“I did.”

“Well, then, drink your tea,” she said, and another woman came into the Hemlock. She did not look at me or my family or anywhere at all. She brushed by my table, very tall, with a very great deal of very wild hair. Her shoes made noise on the floor. She stopped at a rack of envelopes and grabbed the first one she saw, tossing a coin to the woman behind the counter, who caught it almost without looking, and then she was back out the door. With all the tea on all the tables, it looked like one of her pockets was

steaming. I was the only one who had noticed her. She did not look back.

There are two good reasons to put your napkin in your lap. One is that food might spill in your lap, and it is better to stain the napkin than your clothing. The other is that it can serve as a perfect hiding place. Practically nobody is nosy enough to take the napkin off a lap to see what is hidden there. I sighed deeply and stared down at my lap, as if I were lost in thought, and then quickly and quietly I unfolded and read the note the woman had dropped there.

CLIMB OUT THE WINDOW IN THE BATHROOM AND MEET ME IN THE ALLEY BEHIND THIS SHOP. I WILL BE WAITING IN THE GREEN ROADSTER. YOU HAVE FIVE MINUTES. —S

“Roadster,” I knew, was a fancy word for “car,” and I couldn’t help but wonder what kind

of person would take the time to write “roadster” when the word “car” would do. I also couldn’t help but wonder what sort of person would sign a secret note, even if they only signed the letter S. A secret note is secret. There is no reason to sign it.

“Are you OK, son?”

“I need to excuse myself,” I said, and stood up. I put the napkin down on the table but kept the note crumpled up in my hand.

“Drink your tea.”

“Mother,” I said.

“Let him go, dear,” said the man in the brown suit. “He’s almost thirteen. It’s a difficult age.”

I stood up and walked to the back of the Hemlock. Probably one minute had passed already. The woman behind the counter watched me look this way and that. In restaurants they always make you ask where the bathroom is, even

when there’s nothing else you could be looking for. I told myself not to be embarrassed.

“If I were a bathroom,” I said to the woman, “where would I be?”

She pointed to a small hallway. I noticed the coin was still in her hand. I stepped quickly down the hallway without looking back. I would not see the Hemlock Tearoom and Stationery Shop again for years and years.

I walked into the bathroom and saw that I was not alone. I could think of only two things to do in a bathroom while waiting to be alone. I did one of them, which was to stand at the sink and splash some cold water on my face. I took the opportunity to wrap the note in a paper towel and then run the thing under the water so it was a wet mess. I threw it away. Probably nobody would look for it.

A man came out of the stall and caught my eye in the mirror. “Are you all right?” he asked

me. I must have looked nervous.

“I had the eggs,” I said, and he washed his hands sympathetically and left. I turned off the water and looked at the only window. It was small and square and had a very simple latch. A child could open it, which was good, because I was a child. The problem was that it was ten feet above me, in a high corner of the bathroom. Even standing on tiptoes, I couldn’t reach the point where I’d have to stand if I wanted to reach the point to open the latch. Any age was a difficult age for someone needing to get through that window.

I walked into the bathroom stall. Behind the toilet was a large parcel wrapped in brown paper and string, but wrapped loosely, as if nobody cared whether you opened it or not. Leaned up against the wall like that, it didn’t look interesting. It looked like something the Hemlock needed, or a piece of equipment a

plumber had left behind. It looked like none of your business. I dragged it into the middle of the stall and shut the door behind me as I tore open the paper. I didn’t lock it. A man with large shoulders could force open a door like that even if it were locked.

It was a folding ladder. I knew it was there. I’d put it there myself.

It was probably one minute to find the note, one to walk to the bathroom, one to wait for the man to leave, and two to set up the ladder, unlatch the window, and half-jump, half-slide out the window into a small puddle in the alley. That’s five minutes. I brushed muddy water off my pants. The roadster was small and green and looked like it had once been a race car, but now it had cracks and creaks all along its curved body. The roadster had been neglected. No one had taken care of it, and now it was too late. The woman was frowning behind the steering wheel

when I got in. Her hair was now wrestled into place by a small leather helmet. The windows were rolled down, and the rainy air matched the mood in the car.

“I’m S. Theodora Markson,” she said.

“I’m Lemony Snicket,” I said, and handed her an envelope I had in my pocket. Inside was something we called a letter of introduction, just a few paragraphs describing me as somebody who was an excellent reader, a good cook, a mediocre musician, and an awful quarreler. I had been instructed not to read my letter of introduction, and it had taken me some time to slip the envelope open and then reseal it.

“I know who you are,” she said, and tossed the envelope into the backseat. She was staring through the windshield like we were already on the road. “There’s been a change of plans. We’re in a great hurry. The situation is more complicated than you understand or than I am

in a position to explain to you under the present circumstances.”

“Under the present circumstances,” I repeated. “You mean, right now?”

“Of course that’s what I mean.”

“If we’re in a great hurry, why didn’t you just say ‘right now’?”

She reached across my lap and pushed open the door. “Get out,” she said.

“What?”

“I will not be spoken to this way. Your predecessor, the young man who worked under me before you, he never spoke to me this way. Never. Get out.”

“I’m sorry,” I said.

“Get out.”

“I’m sorry,” I said.

“Do you want to work under me, Snicket? Do you want me to be your chaperone?”

I stared out at the alley. “Yes,” I said.

“Then know this: I am not your friend. I am not your teacher. I am not a parent or a guardian or anyone who will take care of you. I am your chaperone, and you are my apprentice, a word which here means ‘person who works under me and does absolutely everything I tell him to do.’”

“I’m contrite,” I said, “a word which here means—”

“You already said you were sorry,” S. Theodora Markson said. “Don’t repeat yourself. It’s not only repetitive, it’s redundant, and people have heard it before. It’s not proper. It’s not sensible. I am S. Theodora Markson. You may call me Theodora or Markson. You are my apprentice. You work under me, and you will do everything I tell you to do. I will call you Snicket. There is no easy way to train an apprentice. My two tools are example and nagging. I will show you what it is I do, and then I will tell

you to do other things yourself. Do you understand?”

“What’s the S stand for?”

“Stop asking the wrong questions,” she replied, and started the engine. “You probably think you know everything, Snicket. You are probably very proud of yourself for graduating, and for managing to sneak out of a bathroom window in five and a half minutes. But you know nothing.”

S. Theodora Markson took one of her gloved hands off the steering wheel and reached up to the dashboard of the roadster. I noticed for the first time a teacup, still steaming. The side of the cup read HEMLOCK.

“You probably didn’t even notice I took your tea, Snicket,” she said, and then reached across me and dumped the tea out the window. It steamed on the ground, and for a few seconds we watched an eerie cloud rise into the air of the

alley. The smell was sweet and wrong, like a dangerous flower.

“Laudanum,” she said. “It’s an opiate. It’s a medicament. It’s a sleeping draught.” She turned and looked at me for the first time. She looked pleasant enough, I would say, though I wouldn’t say it to her. She looked like a woman with a great deal to do, which is what I was counting on. “Three sips of that and you would have been incoherent, a word which here means mumbling crazy talk and nearly unconscious. You never would have caught that train, Snicket. Your parents would have hurried you out of that place and taken you someplace else, someplace I assure you that you do not want to be.”

The cloud disappeared, but I kept staring at it. I felt all alone in the alley. If I had drunk my tea, I never would have been in that roadster, and if I had not been in that roadster, I never would have ended up falling into the wrong tree, or walking into the wrong basement,

or destroying the wrong library, or finding all the other wrong answers to the wrong questions I was asking. She was right, S. Theodora Markson. There was no one to take care of me. I was hungry. I shut the door of the car and looked her in the eye.

“Those weren’t my parents,” I said, and off we went.

CHAPTER TWO

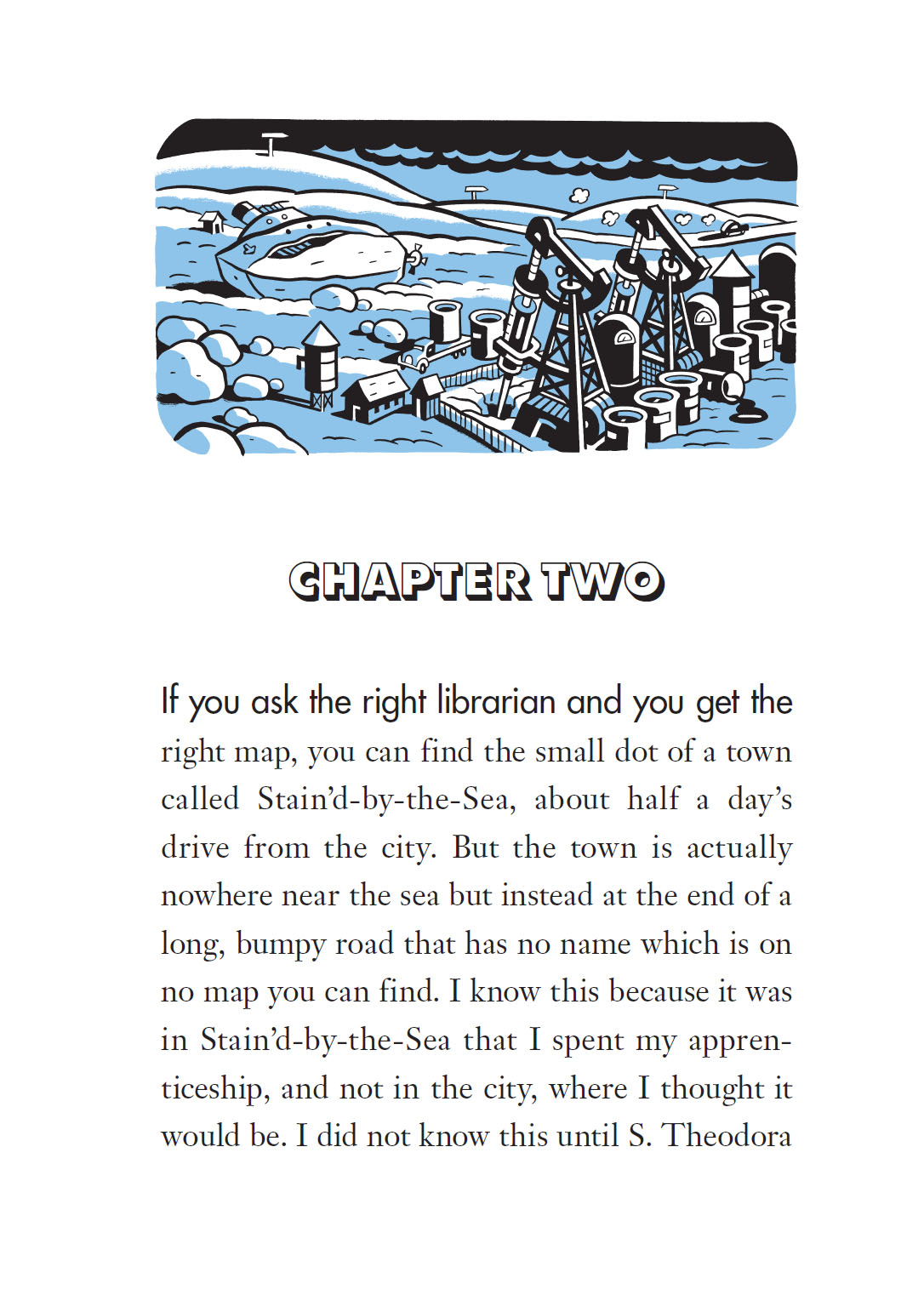

If you ask the right librarian and you get the right map, you can find the small dot of a town called Stain’d-by-the-Sea, about half a day’s drive from the city. But the town is actually nowhere near the sea but instead at the end of a long, bumpy road that has no name which is on no map you can find. I know this because it was in Stain’d-by-the-Sea that I spent my apprenticeship, and not in the city, where I thought it would be. I did not know this until S. Theodora

Markson drove the roadster past the train station without even slowing down.

“Aren’t we taking the train?” I asked.

“That’s another wrong question,” she said. “I told you there’s been a change of plans. The map is not the territory. That’s an expression which means the world does not match the picture in our heads.”

“I thought we were working across town.”

“That’s exactly what I mean, Snicket. You thought we were working across town, but we are not working in the city at all.”

My stomach fell to the floor of the car, which rattled as we took a sharp turn around a construction site. A team of workers were digging up the street to start work on the Fountain of Victorious Finance. Tomorrow, if it were possible for an apprentice to sneak away for lunch, I was supposed to meet someone right there, in hopes of measuring how deep the hole was that they were digging. I’d managed to acquire

a new measuring tape for just that purpose, one that stretched out a very long distance and then scurried back into its holder with a satisfying click. The holder was shaped like a bat, and the tape measure was red, as if the bat had a very long tongue. I realized I would never see it again.

“My suitcase,” I said, “is at the train station.”

“I purchased some clothes for you,” Theodora said, and tilted her helmeted head toward the backseat, where I saw a small, bruised suitcase. “I was given your measurements, so hopefully they fit. If they don’t, you will have to either lose or gain weight or height. They’re unremarkable clothes. The idea is not to attract attention.”

I thought that wearing clothes either too big or too small for me would be likely to attract attention, and I thought of the small stack of books I had tucked next to the bat. One of them was very important. It was a history of the city’s underground sewer system. I had planned to

take a few notes on chapter 5 of the book, on the train across town. When I disembarked at Bellamy Station, I would crumple the notes into a ball and toss them to my associate without being seen. She would be standing at the magazine rack at Bellamy Books. It was all mapped out, but now the territory was different. She would read magazines for hours before catching her own train to her own apprenticeship, but then what would she do? What would I do? I scowled out the window and asked myself these and other hopeless questions.

“Your reticence is not appreciated,” Theodora said, breaking my sour silence. “‘Reticence’ is a word which here means not talking enough. Say something, Snicket.”

“Are we there yet?” I asked hopefully, although everyone knows that is the wrong question to ask the driver of a car. “Where are we going?” I tried instead, but for a moment Theodora did not answer. She was biting her

lip, as if she were also disappointed about something, so I tried one more question that I thought she might like better. “What does the S stand for?”

“Someplace else,” she replied, and it was true. Before long we had passed out of the neighborhood, and then out of the district, and then out of the city altogether and were driving along a very twisty road that made me grateful I had eaten little. The air had such a curious smell that we had to close the windows of the roadster, and it looked like rain. I stared out the

window and watched the day grow later. Few cars were on the road, but all of them were in better shape than Theodora’s. Twice I almost fell asleep thinking of places and people in the city that were dearly important to me, and the distance between them and myself growing and growing until the distance grew so vast that even the longest-tongued bat in the world could not lick the life I was leaving behind.

A new sound rattled me out of my thoughts. The road had become rough and crackly under the vehicle’s wheels as Theodora took us down a hill so steep and long I could not see the bottom of it through the roadster’s dirty windows.

“We’re driving on seashells,” my chaperone said in explanation. “This last part of the journey is all seashells and stones.”

“Who would pave a road like that?”

“Wrong question, Snicket,” she replied. “Nobody paved it, and it’s not really a road. This entire valley used to be underwater. It was drained some years back. You can see why it would be absolutely impossible to take the train.”

A whistle blew right then. I decided not to say anything. Theodora glared at me anyway and then frowned out the window. A distance away was the hurried, slender shape of a long train, balancing high above the bumpy valley where we were driving. The train tracks were

on a long, high bridge, which curved out from the shore to reach an island that was now just a mountain of stones rising out of the drained valley. Theodora turned the roadster toward the island, and as we approached I could see a group of buildings—faded brick buildings enclosed by a faded brick wall. A school, perhaps, or the estate of a dull family. The buildings had once been elegant, but many of the windows were shattered and gone, and there were no signs of life. I was surprised to hear, just as the roadster passed directly under the bridge, the low, loud clanging of a bell, from a high brick tower that looked abandoned and sad on a pile of rocks.