полная версия

полная версияNeuralgia and the Diseases that Resemble it

I might expand this chapter on the complications of neuralgia to a very much greater length; but, as regards the clinical history of these affections, it is perhaps better not to occupy more time and space. It will, however, be necessary to return to the consideration of the subject in connection with Pathology.

CHAPTER III.

PATHOLOGY AND ETIOLOGY OF NEURALGIA

The pathology and the etiology of neuralgia cannot be considered apart; they must be discussed together at every step. I do not mean to say that neuralgia is singular among diseases in this respect; it seems to me merely a case in which the intrinsic defects of the conventional system of separating the "causes" of disease from its pathology happen to be more glaring and more easily demonstrable than usual.

Neuralgia possesses no "pathology," if by that word we intend to signify the knowledge of definite anatomical changes always associated with the disease, in a manner that we can exhibit or exactly describe. It also possesses no demonstrable causes, if we employ the word "causes" in the old metaphysical sense. And yet I am very far from admitting, what seems to be so generally taken for granted, that we know less about the seat, the nature, and the conditions of neuralgia than of other diseases. On the contrary, I believe, with all deference to the supporters of the ordinary opinion, that we know more about neuralgia, in all these respects, than we do about pneumonia, only our knowledge is not of the superficial and obvious kind, but requires the aid of reason and reflection to develop and turn it to account. It has long been a matter of surprise to me, that even able writers have been content to talk about this disease (as, indeed, they have been content to speak of many nervous diseases) with an inexplicable looseness of phraseology. They speak of its "protean" forms; whereas, in my humble judgment, its forms are by no means specially numerous. They insist on the mysterious and unintelligible manner of its outbreaks, remissions and departure; but I shall try to show that, although, in the investigation of neuralgia, we are continually stopped in particular lines of inquiry by what seems to be ultimate facts, susceptible of no further immediate solution, the channels of information open to us are so unusually numerous as to enable us to accumulate a mass of information which, upon further reflection, will be found to furnish the materials of a synthesis of the disease singularly clear and effective for every practical purpose of the physician. In one important particular I especially hope to convince the reader that a large proportion of the mystification as to the pathology of neuralgia is gratuitous, and the result of great carelessness in estimating the comparative value of different facts. I hope to show clearly that, as regards both the seat of what must be the essential part of the morbid process, and the general nature of the process itself, we possess very definite information indeed. I expect, in short, to convince most readers that the essential seat of every true neuralgia is the posterior root of the spinal nerve in which the pain is felt, and that the essential condition of the tissue of that nerve-root is atrophy, which is usually non-inflammatory in origin. This doctrine seems, at first sight, presumptuous,16 in the confessed absence or extreme scarcity of dissections which even bear at all upon the question. But one source of the extraordinary interest which the pathology of neuralgia has long possessed for me resides in this very fact, that I am convinced we can demonstrate the above apparently difficult theorem by means of pathological observations on the living subject, taken in conjunction with physiological experiments, and with only the aid of a very few isolated facts of positive morbid anatomy. I need hardly say that I am none the less anxious for that further assurance which we shall one day, perhaps, obtain by means of greatly-improved processes for microscopic detection of minute changes in nerve-centres; but, looking to the necessary rarity of opportunities for post-mortem examinations of the nervous system in any but the most advanced stages of neuralgias, it will hardly be disputed that, if I am right in my main position, we are singularly fortunate to be so unusually independent of the need for this source of information.

1. The first fact which strikes me as of decided importance is the position of neuralgia as an hereditary neurosis; and this character of the disease is so pregnant with significance, that I shall take some considerable pains to put the fact beyond doubt in the reader's mind.

There are two series of facts which support the theory of the inheritance of the neuralgic tendency: (a) instances in which the parent of the sufferer had also been affected with the disease; and (b) instances in which the family history of the patient being traced out more at large it appeared that, among the members of two or more generations, while one, two, or more individuals had been actually neuralgic, other members had suffered from other serious neuroses (such as insanity, epilepsy, paralysis, chorea, and the tendency to uncontrollable alcoholic excesses), and, in many instances, that this neurotic disposition was complicated with a tendency to phthisis.

(a) The question of the direct transmission of neuralgia itself from the parent seems the easiest of decision, though even this cannot always be satisfactorily cleared up by the hospital patients, among whom one collects the largest part of one's clinical materials. However, I have been at the pains of investigating a hundred cases of all kinds of neuralgia, seen in hospital and private practice, with the following results: twenty-four gave distinct evidence that one or other parent had suffered from some variety of neuralgia; fifty-eight gave a distinctly negative answer; and eighteen would not undertake to give any answer at all. Among the twenty-four affirmatives are inserted none in which the history of the parent's affection did not clearly specify the liability to localized pain, of intermitting type, but recurring always in the same situation during the same illness. In three of these twenty-four instances, the patient stated that both parents had suffered from such attacks, and, in one of these, it appeared that the grandfather had likewise suffered.

(b) The question of the tendency of a family, during two or more generations, to severe neuroses of more or less varying kinds, including neuralgia, is difficult to work out perfectly, though in a large number of instances we may get enough information to be very useful. I have spent much time and trouble in endeavoring to collect such information; but there are two main difficulties in connection with all such attempts. From hospital patients you frequently can get no reliable information whatever respecting any members of the family farther back than the immediate parents; and, even respecting uncles and aunts and first cousins, it is often impossible to learn any thing. And when you get to a higher class of society, especially when you approach the highest, although the information may exist, it may be withheld, or you may be purposely mystified. One would doubt beforehand, under these circumstances of difficulty, whether it would be possible to obtain affirmative evidence of the neurotic temperament of the families of neuralgic patients in general; but, in truth, the evidence is so overwhelming in amount, that more than enough can be obtained for our purpose. I shall give, first, the results of one special inquiry which, by the kindness of a patient, I have been able to carry out with more than usual completeness; it relates to the medical genealogy of a sufferer from sciatica; the account is fairly complete for four generations. The great-grandfather was a man of splendid physique (an only son), who lived very freely, but died an old man. His children were three sons, one of whom (though strictly temperate) was a man of eccentric and somewhat violent temper, and suffered from a spasmodic facial affection. This one, the grandfather of my patient, married a lady who died of phthisis, and among the ten children she bore him, two sons died of phthisis, two sons became chronically insane, one son died, probably of mesenteric tubercular disease (aged fifty-six), two sons are still alive at very advanced ages, and have always been perfectly healthy and strong; one daughter died in middle age, it is not certain from what cause; one daughter lived healthily to the age of eighty, and then was attacked by facial erysipelas, followed by violent and intractable epileptiform tic, which clung to her for the remaining four years of her life; and the remaining daughter, an occasional sufferer from migraine, died at the age of sixty-seven, almost accidentally, from exhausting summer diarrhœa. The fourth generation, in this branch of the family, consisted of thirty-one individuals; of whom seven have died of phthisis, or scrofulous disease; one from accidental violence, one from rheumatic fever, one from scarlet fever; and among the surviving twenty-two one has been insane, but recovered; two are decided neuralgics; one is occasionally migraineuse, and once had a smart attack of facial erysipelas, corneitis, and iritis, as the climax to a severe neuralgic attack; one has been a sufferer from chorea; one has become phthisical; one developed strumous disease, but has fairly recovered from it. The remaining fifteen enjoy good health, but are distinguished, almost without exception, by a markedly neurotic temperament, indicated by an anxious tendency of mind, quickness of perception, æsthetic taste, disposition to alternations of impulse and procrastination. Of the young fifth generation growing up, there have been twenty-five children, of whom only one has died (from fever), the rest are apparently healthy (most of them specially so); but, as few have yet reached the age for the development either of phthisis or of neurotic diseases, the future of this generation can only be guessed at. [It is unnecessary to trace the other descendants of the second generation, but I may state that their medical history, also, strongly supports the theory of inheritance of the neurotic tendency, and of the influence of an imported element of phthisis in aggravating the latter.] I suspect that, as regards the young children now growing up, everything will depend on the care with which they are fed, and the kind of moral influences brought to bear on them, two subjects which will be fully dwelt on in the chapter on Treatment.

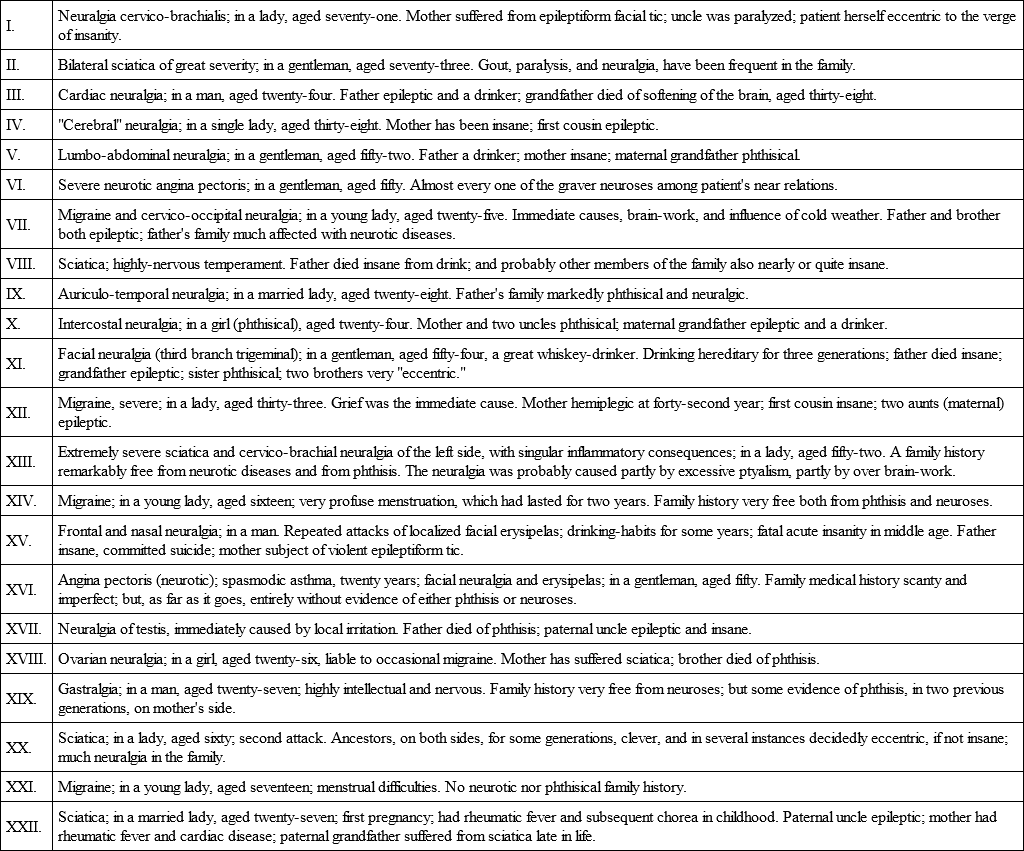

Of less perfect inquiries on the subject of neurotic disposition inherited by neuralgic patients, I have made a great number, though I regret to say that I have not attempted the task in the whole number of those from whom I inquired as to direct inheritance of neuralgia from their parents. However, in eighty-three cases this was done with all possible care, and any deficiency of completeness in the results is not my fault. I shall take first those that were private patients, twenty-two in number, respecting whom, I may say, that the evidence is of the best, as far as it goes, since I was better able to discriminate as to the worth of statements, than in dealing with hospital patients, and have rejected every case in which the informant did not seem intelligent enough, or otherwise to have the means, to give a thoroughly reliable account.

No one, I think, can look down the above list and fail to be struck with the great preponderance of cases in which the general neurotic temperament plainly existed in the patients' families; and let me add that, in not a few of these cases, the neuralgia in the individual under observation might have been easily set down as dependent merely upon peripheral irritation, which, indeed, plainly did act as a concurrent cause.

Fortunately, however, I am not dependent upon my own evidence alone, for the proofs of the proposition that neuralgia is eminently a development of hereditary neuroses. The great French alienists, Morel and Moreau of Tours, some years ago laid the foundations of the doctrine of hereditary neurosis. They enforced this chiefly with reference to the manner in which insanity is transmitted through a chain of variously-neurotic members of a family stock; and Moreau laid special stress on the deeply interesting connection of the phthisical with the neurotic tendency. Since then various observers have insisted on the same thing. Of late, Dr. Maudsley has worked out this subject with great ability, in his work "On the Physiology and Pathology of Mind," and in his recent "Gulstonian Lectures;" and Dr. Blandford dwells on it with emphasis in his interesting "Lectures on Insanity." [Dr. Blandford does not, however, admit that the phthisical diathesis has any such close and causal relation with neuroses as has been imagined by some recent pathologists; and, on the other hand, he points out that phthisis in neurotic subjects, e. g., the insane, must, in a large measure, be considered the product of the accidentally unhealthy circumstances in which they pass their lives. In the latter opinion I entirely agree.] Indeed, it may be taken as a recognized fact, among the more advanced students of nervous diseases, that hereditary neurosis is an important antecedent of neuralgia, in at least a very large number of instances. I shall conclude this part of the argument by stating the general results of my inquiries respecting sixty-one hospital patients. Of these cases, twenty-two were migraine, or some other affection of the ophthalmic division of the fifth nerve; seven were sciatica; two were epileptiform facial tic; ten were neuralgias affecting chiefly the second and third divisions of the fifth nerve; three were intercostal neuralgias pure; one was intercostal neuralgia plus anginoid pain; seven were intercostal neuralgias with zoster; three were brachial neuralgias; and five were abdominal neuralgias (hepatic, gastric, mesenteric, etc.) Of eighty-three hospital and private patients [It must be understood that the respective numbers do not indicate with any accuracy the relative frequency of the different neuralgias as seen in my practice. (Sciatica, e. g., was proportionally more frequent.) They represent but a small part of the neuralgic patients whom I have seen during fourteen years of dispensary, hospital, and private practice, and they were selected for inquiry merely because I happened to be able to give the time for the necessary questions. Every one who knows out-patient practice will understand how seldom this happened.] I obtained evidence of the presence, among blood-relations, of the following diseases: Epilepsy, fourteen cases (eight were examples of migraine); hemiplegia or paraplegia, nine cases; insanity, twelve cases; drunken habits, fourteen cases; "consumption," eighteen cases; "St. Vitus's dance," four cases. I am well aware that these figures must be taken with caution, and that considerable doubt must rest on the accuracy of some of these details, more especially with regard to "epilepsy," as it was impossible, with the greatest care, to be sure that this was not given, by mistake, for hysteria in some cases; and the same may apply to the statement that relations had suffered from "consumption." The facts are given for what they are worth, and with the express reservation that their total reliability is far less than that of the accounts obtained respecting private patients belonging to the more educated classes. But, in one respect, viz., as regards drunken habits, it is possible that a truer estimate is gained from the statements of hospital patients than from those of private patients, who would usually be more prone to reticence on such a topic.

The evidence as to the hereditary character of neuralgia assumes a yet higher importance when supplemented by the facts respecting the alternations of neuralgia with other neuroses as the same individuals. Every practitioner must be aware how frequent is the latter occurrence. Nothing is more common, for example, than to see insanity developed as the climax of minor nervous troubles, especially of neuralgia. And there is one form of neuralgia, the true epileptiform tic, which is intimately bound up with a mental condition of the nature of melancholia, and even with the markedly suicidal form of the latter affection. I have lately had under my care a lady in whom the prodromata of a severe facial neuralgia were mental; the disturbance commenced with frightful dreams, and there was great mental agitation even before the pain broke out; this disturbance of mind, however, continued during the whole period of the neuralgia, and was relieved simultaneously with the cessation of the attacks of pain. This is contrary to what happens in some cases; thus, Dr. Maudsley quotes the case of an able divine who was liable to alternations of neuralgia and insanity, the one affection disappearing when the other prevailed. Dr. Blandford has met with several instances in which neuralgia has been followed by insanity, the pain vanishing during the mental disturbance, and reappearing as the latter passed away. And he remarks that, in the transition of a neuralgia (to mental affection), we may well believe that the neurotic affection is merely changed from one centre to another, from the centres of sensation to those of mind. He says that the ultimate prognosis of such cases is bad; a point to which we shall have to refer again.

The prominent place which quasi-neuralgic pains hold in the earlier history of locomotor ataxy is a fact that cannot but engage attention. In this volume we have not treated these pains as belonging to the truly neuralgic class, for the very practical reason that they are but incidents in a most important organic disease, and that in a diagnostic and prognostic point of view it is necessary to dwell on their connection with that disease. But, in considering the pathological relations of neuralgia, it would be improper to omit the consideration of the pains of locomotor ataxy, which bear a striking semblance to neuralgic pains. The fact that they are an almost if not quite constant feature of a disease which is from first to last an atrophic affection (mainly of the posterior columns of the cord), in which the posterior roots of the nerves are almost always deeply involved, has a bearing on our present inquiry too obvious to need further remark.

Equally important to our investigation is the fact that pains, closely resembling neuralgia, are not very uncommonly a part of the phenomena of commencing, and more frequently of receding, spinal paralysis. I have the notes of three cases of partial recovery from paraplegia, in all of which the patients remained for years, in one case for nearly twenty years (ending with death), the victims to a singularly intractable neuralgia of both lower extremities. In the worst of the cases the patient was the victim of excessive and continuous labor at literary work of a kind which hardly exercised the mental powers, but was extremely exhausting to the general power of the nervous system; he broke down at about the age of fifty, but dragged on a painful existence for the long period above mentioned.

We are also certainly entitled to adduce the example of the so-called neuralgic form of chronic alcoholism as an instance of the close relationship of neuralgia to other central neuroses. I refer to those cases, more common perhaps than is generally admitted, in which pains in the extremities, often quite resembling neuralgia in their intermittence, are either superadded to or take the place of the muscular tremors and general restlessness that are more popularly considered as the essential nervous phenomena of chronic alcoholic poisoning. That the pains are usually bilateral, and more diffuse in their character than those of ordinary neuralgia, is a fact which it is not difficult to explain by the modus operandi of the cause; but we shall have more to say on the general relations of alcoholic excess to neuralgia presently. The pains themselves will be fully described in the second part of this book, which treats of the affections that simulate neuralgia; here we need only remark that it is not uncommon for them to occur interchangeably with true neuralgia in the same person.

The occasional interchangeability of migraine with epilepsy is a well-known fact; every practitioner who has seen much of the latter disease will have seen some cases in which the patient had been liable, at some point of his medical history, to "sick-headaches" of a truly neuralgic kind; although it is quite true, as Dr. Reynolds points out, that the kind of sensorial disorder specially premonitory of the attacks consists rather in indefinable distressing sensations, than in actual pain. The genealogical connection between migraine and epilepsy is, as I have already stated, apparently very close. Such instances as one mentioned by Eulenburg are rightly explained by him; it is the case of a girl who suffered at an unusually early age (nine) from migraine; her mother had been a migraineuse, and her sister was epileptic; the strong neurotic family tendency is believed by Eulenburg to account for the appearance of migraine at such a period of life.

This seems the fitting place to introduce some special remarks on migraine in its relations to other neuralgias of the head, because Eulenburg has mentioned and combated my view, according to which migraine is a mere variety of neuralgia of the ophthalmic division of the fifth nerve. I call it my view, because, though several other authors had previously expressed it, I was first lead to entertain it by observations made before I had studied their works, and especially by the impressive teaching of my own case, as to which more will be presently said. Eulenburg, though he fully allows that migraine is a neuralgia, urges a series of objections to the identification of migraine with ophthalmic neuralgias; of which objections one, based on the doctrine of Du Bois Reymond as to the action of the sympathetic in migraine, must be reserved for consideration when we discuss the general pathology of the vaso-motor complications of neuralgia. The other grounds of distinction that he urges are the following: In the first place, he remarks that the site of the pain is by far less distinctly referred to definite foci on the outside of the skull than in trigeminal neuralgia; the patient's sensations very usually lead him to declare that the pain is in the brain itself. Secondly, he says that the points douloureux (in Valleix's sense) are almost constantly absent in true migraine. Thirdly, he specifies the character of the pain in migraine – dull, boring, straining, etc. – as differing from that of trigeminal neuralgia, which is ordinarily much more acute and darting. Fourthly, he notes the long duration of individual attacks of migraine, and the long intervals (very commonly three or four weeks) between them. Fifthly, he dwells on the frequent prodromata of migraine referable to the organs of sense (flashes before the eyes, noises in the ears), or to the stomach (nausea), or more generally to the reflex functions of the medulla oblongata (e. g., convulsive rigors, excessive yawning, etc.)

Now, I should have nothing to say against the accuracy of this description, did it apply merely to the distinctions between highly-typical cases of the "sick-headache" of the period of bodily development, and highly-typical cases of the ophthalmic neuralgias which are commonest in the middle and later periods of life; nor indeed should I greatly care if it were finally decided that migraine and clavus should be separated from the true trigeminal neuralgiæ, provided the following points were well impressed on the minds of practitioners. In the first place, I must insist that in my own experience the great majority of undoubtedly neuralgic headaches, which subordinate stomach disturbance, are far less sharply separated than the above description would allow from the unmistakable trigeminal neuralgias; it is only a minority of cases that wear this extreme type, and a far larger number shade imperceptibly away toward the type of ophthalmic neuralgia pure and simple. And so, again, of the so-called clavus there is every variety, from a form bordering closely on the migraine type to another, differing in nothing from an unusually severe ocular and frontal neuralgia of the fifth, except in the presence of a tremendously painful parietal focus. But the fact on which I would most particularly insist is one that was first taught me by my personal experience, viz., that migraine is, with extraordinary frequency, the primary or youthful type of a neuralgia which, in later years, entirely loses the special characters of sick-headache, and assumes those of ordinary frontal neuralgia, with or without complications. In my own case, the "sick-headache" character of the affection was strongly marked during the first two or three years, after which time it gradually but steadily lost all tendencies to stomach complications, and, what is more, the type of the recurrence became entirely changed. Yet it is quite impossible to believe that the malady is now a different one, in any essential pathological point, from what it was at first; if any disproof of this were needed, it might be remarked that the singular series of secondary trophic changes which have complicated my case have been impartially distributed between the respective periods when the affection was frankly migraineuse, when it was mixed, and when it was simply ophthalmic neuralgia (as it is at present;) indeed, some of the most decided of these trophic complications (orbital periostitis, corneal ulceration, fibrous obstruction of the nasal duct) occurred within the period in which every attack of pain, unless I succeeded in getting to sleep very shortly, ended in violent vomiting. The experience thus gained has made me very attentive to the past history of those who, in later life, complain of frontal neuralgia without stomach complication, and it is surprising to find in how many cases patients, who at first declare that they never had neuralgia before, on reflection will recall the fact that they were often "bilious" in their youth; which "biliousness" turns out to have been regularly preceded by one-sided headache, and to have been severe in proportion to the severity and duration of that previous headache.