полная версия

полная версияEngland in the Days of Old

In the reign of Henry VIII., Erasmus visited England, and he relates that many herds of bears were maintained at the Court for the purpose of being baited. We are further told by him that the rich nobles had their bearwards, and the Royal establishment its Master of the King’s Bears.

Men were not wanting to raise their voices against this brutal sport even at the time kings favoured it. Towards the close of the reign of Henry VIII., Crowley wrote some lines, which we have modernised, as follows: —

“What folly is this to keep with dangerA great mastiff dog, and foul, ugly bear,And to this intent to see these two fightWith terrible tearing, a full ugly sight.And methinks these men are most fools of allWhose store of money is but very small,And yet every Sunday they will surely spendA penny or two, the bear-ward’s living to mend.At Paris Garden, each Sunday, a man shall not failTo find two or three hundred for the bear-ward’s vale;One halfpenny a piece they use for to giveWhen some have not more in their purses, I believe.Well, at the last day their conscience will declareThat the poor ought to have all that they may spare,If you therefore go to witness a bear fightBe sure that God His curse will upon you alight.”We may recognise the zeal of the writer, but we cannot commend the merits of his poetry.

When Princess Elizabeth was confined at Hatfield House, she was visited by her sister, Queen Mary. On the morning after her arrival, after mass was over, a grand entertainment of bear-baiting took place, much to their enjoyment.

Elizabeth, as a princess, took a delight in this sport, and when she occupied the throne she gave it her support. When the theatre, in the palmy days of Shakespeare and Burbage, was attracting a larger share of public patronage than the bear garden, she waxed indignant, and in 1591 an order was issued from the Privy Council, forbidding “plays to be performed on Thursdays because bear-baiting and such pastimes had usually been practised.” The Lord Mayor followed the order with an injunction in which it was stated “that in divers places the players are not to recite their plays to the great hurt and destruction of the game of bear-baiting and suchlike pastimes, which are maintained for Her Majesty’s pleasure.”

During the famous visit in 1575, of Queen Elizabeth to the Earl of Leicester, at Kenilworth Castle, baiting thirteen bears by ban dogs (a small kind of mastiff), was one of the entertainments provided for the royal guest.

History furnishes several instances of the Queen having animals baited for the diversion of Ambassadors. On May 25, 1559, the French Ambassadors dined with the Queen, and after dinner bulls and bears were baited by English dogs. She and her guests stood looking at the pastime until six o’clock. Next day the visitors went by water to the Paris Garden, where similar sports were held. In 1586, the Danish Ambassadors were received at Greenwich by Her Majesty, and bull and bear baiting were part of the amusements provided. Towards the close of her reign, the Queen entertained another set of Ambassadors with a bear-bait at the Cockpit near St. James’s. Baiting animals appears to have been the chief form of amusement provided by the Queen for foreign visitors.

Edmund Alleyn, founder of Dulwich College, was for a long time part owner of the bear gardens at Southwark. Mr. Edward Walford thinks that he was obliged to become a proprietor to make good his position as a player, and to carry out his theatrical designs. He had to purchase the patent office of “Beare ward,” or “Master of the King’s Beares.” Alleyn is reputed to have had a well stocked garden. On one occasion, when Queen Elizabeth wanted a grand display of bear-baiting, Sir John Dorrington, the chief master of Her Majesty’s “Games of Bulls and Bears,” applied and obtained animals from Alleyn.

The following advertisement written in a large hand was found amongst the Alleyn papers, and is supposed to be the original placard exhibited at the entrance of the bear-garden. It is believed to date back to the days of James I.: —

“Tomorrowe being Thursdaie shalbe seen at the Bear-gardin on the banckside a greate mach plaid by the gamsters of Essex, who hath chalenged all comers whatsoever to plaie v dogs at the single beare for v pounds, and also to wearie a bull dead at the stake; and for your better content shall have plasent sport with the horse and ape and whiping of the blind beare. Vivat Rex!”

The public had to be protected from the dogs employed in this sport. From the “Archives of Winchester,” published 1856, a work compiled from the city records, we find it stated. – “By an Ordinance of the 4th of August, in the twenty-eighth year of the reign of Elizabeth, bull-dogs were prohibited roving throughout the city unmuzzled. Itm. – That noe person within this citie shall suffer or permit any of theire Mastife Doggs to goe unmusselled, uppon paine of everie defalte herein of 3s. 4d. to be levied by distresse, to the use of the Poore people of the citie.”

James I. was a lover of hunting and other sports, and gave his patronage to bear-baiting. We learn from Nichols’ “Progresses and Processions,” that the King commanded that a bear which had killed a child which had negligently been left in the bear-house of the Tower, be baited to death upon a stage. The order was carried out in presence of a large gathering of spectators.

In a letter written on July 12th, 1623, by Mr. Chamberlain to Sir Dudley Carleton, the following passage occurs: – “The Spanish Ambassador is much delighted in bear-baiting. He was last week at Paris Garden, where they showed him all the pleasure they could both with bull, bear, and horse, besides jackanapes, and then turned a white bear into the Thames, where the dogs baited him swimming, which was the best sport of all.”

Mr. William Kelly, in his work entitled “Notices Illustrative of the Drama and other Popular Amusements, Chiefly in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries,” has some very curious information relating to bear-baiting. The Leicester town accounts contain entries of many payments given to the bear-wards of Edward VI., Queen Elizabeth, and members of the nobility. Leicester had its bear-garden, but we learn from Mr. Kelly that the local authorities were not content to see the sport there, “as it was introduced at the Mayor’s feast, at the Town Hall, which was attended by many of the nobility and gentry of the neighbourhood.” We may suppose that, taking the place usually occupied by the “interlude,” the bear was baited in the Hall in the interval between the feast and the “banquet” or dessert, and the company, like the Spanish Ambassador, no doubt witnessed the exhibition “with great delight.” Much might be said relating to Leicester, but we must be content with drawing upon Mr. Kelly for one more item. “In the summer of 1589 (probably at the invitation of the Mayor), the High Sheriff, Mr. Skeffington, and ‘divers other gentlemen with him,’ were present at ‘a great beare-beating’ in the town, and were entertained, at the public expense, with wine and sugar, and a present of ‘ten shillings in gold’ was also made.”

A couplet concerning Congleton Church Bible being sold to purchase a bear to bait at the annual feast, has made the town known in all parts of the country. The popular rhyme says: —

“Congleton rare, Congleton rare,Sold the Bible to pay for a bear.”The scandal has been related in prose and poetry by many pens. Natives of the ancient borough are known as “Congleton Bears” – by no means a pleasant epithet. The inhabitants make the best of the story, and tell how just before the wakes their only bear died, and it was feared that they would be unable to obtain another to enjoy their popular sport. The bear-ward was most diligent in collecting money to buy another animal, but after all his exertions he failed to obtain the required amount. He at last made application to the local authorities, and as they had a small sum in the “towne’s boxe” put aside for the purchase of a Bible for the chapel, it was lent, and it is presumed that the sum of 16s. was duly returned, and the scriptures were obtained.

Egerton Leigh, in his “Cheshire Ballads,” has an amusing poem bearing on this subject, and he concludes it as follows: —

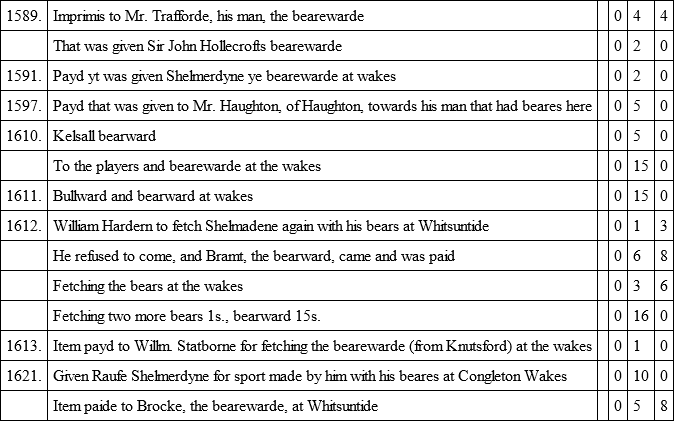

“The townsmen, ’tis true, would explain it away,In those days when Bibles were so dear they say,That they th’ old Bible swopped at the wakes for a bear,Having first bought a new book.Thus shrink they the sneer,And taunts ’gainst their town thus endeavour to clear.”The town accounts show how popular must have been the sport at Congleton. The following are a few items: —

Such are a few examples of the many entries which appear in the Congleton town accounts relating to bear-baiting.

Congleton is not the only place reproached for selling the church Bible for enabling the inhabitants to enjoy the pastime of bear-baiting. Two miles distant from Rugby is the village of Clifton, and, says a couplet,

“Clifton-upon-Dunsmore, in Warwickshire,Sold the church Bible to buy a bear.”Another version of the old rhyme is as follows: —

“The People of Clifton-super-DunsmoreSold ye Church Byble to buy a bayre.”There is a tradition that in the days of old the Bible was removed from the Parish Church of Ecclesfield and pawned by the churchwardens to provide the means of a bear-baiting. Some accounts state this occurred at Bradfield, and not at Ecclesfield. The “bull-and-bear stake” at the latter Yorkshire village was near the churchyard.

Under the Commonwealth this pastime was not permitted, but when the Stuarts were once more on the throne bear-baiting and other sports became popular.

Hockley-in-the-Hole, near Clerkenwell, in the days of Addison, was a favourite place for the amusement. There is a reference to the subject in the Spectator of August 11th, 1731, wherein it is suggested that those who go to the theatres for a laugh should “seek their diversion at the bear garden, where reason and good manners have no right to disturb them.”

Gay, in his “Trivia,” devotes some lines to this subject. He says: —

“Experienced men inured to city waysNeed not the calendar to count their days,When through the town, with slow and solemn air,Led by the nostril walks the muzzled bear;Behind him moves, majestically dull,The pride of Hockley Hole, the surly bull,Learn hence the periods of the week to name —Mondays and Thursdays are the days of game.”Towards the close of the last century the pastime, once the pleasure of king’s and queens and the highest nobles in the land, was mainly upheld by the working classes. A bill, in 1802, was introduced into the House of Commons to abolish baiting animals. The measure received the support of Courtenay, Sheridan, and Wilberforce, men of power in Parliament, but Mr. Windham, who led the opposition, won the day. He pronounced it “as the first result of a conspiracy of the Jacobins and Methodists to render the people grave and serious, preparatory to obtaining their assistance in the furtherance of other anti-national schemes.” The bill was lost by thirteen votes. In 1835, baiting animals was finally stopped by Act of Parliament.

Morris-Dancers

Says Dr. Johnson: “the Morris-Dance, in which bells are jingled, or staves or swords clashed, was learned by the Moors, and was probably a kind of Pyrrhic, or military dance. “Morisco,” says Blount (Span.), a Moor; also a dance, so called, wherein there were usually five men, and a boy dressed in a girl’s habit, whom they called the Maid Marrion, or perhaps Morian, from the Italian Morione, a head-piece, because her head was wont to be gaily trimmed up. Common people called it a Morris-Dance.” Such are the statements made at the commencement of a chapter on this subject in “Brand’s Popular Antiquities.”

It is generally agreed that the Morris-Dance was introduced into this country in the sixteenth century. In the earlier English allusions it is called Morisco, a Moor, and this indicates its origin from Spain. It was popular in France before it was appreciated amongst our countrymen; some antiquaries assert that it came to England from our Gallic neighbours, or even from the Flemings, while others state that when John of Gaunt returned from Spain he was the means of making it known here, but we think there is little truth in the statement.

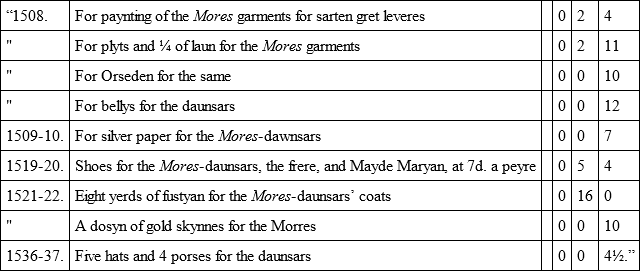

Our countrymen soon united the Morris-Dance with the favourite pageant dance of Robin-hood. We discover many traces of the two dances in sacred as well as profane places. In old churchwarden’s accounts we sometimes find items bearing on this theme. The following entries are drawn from the “Churchwardens’ and Chamberlains’ Books of Kingston-upon-Thames:” —

It is stated that in 1536-37, amongst other clothes belonging to the play of Robin Hood, left in the keeping of the churchwardens, were “a fryer’s coat of russet, with a kyrtle of worsted welted with red cloth, a mowren’s cote of buckram, and 4 Morres daunsars cote of white fustain spangelyed, and two gryne saten cotes, and a dysardd’s cote of cotton, and 6 payre of garters with bells.”

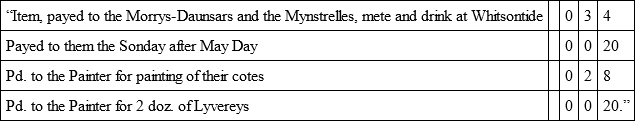

Some curious payments appear in the churchwardens’ accounts of St. Mary’s parish, Reading, and are quoted by Coates, the historian of the town. Under the year 1557, items as follow appear: —

The following is a curious note drawn from the original accounts of St. Giles’, Cripplegate, London: —

“1571. Item, paide in charges by the appointment of the parisshoners, for the settinge forth of a gyaunt morris-dainsers, with vj calyvers and iij boies on horseback, to go in the watche befoore the Lade Maiore uppon Midsomer even, as may appeare by particulars for the furnishinge of same, vj. li. ixs. ixd.”

We learn from the churchwardens’ accounts of Great Marlow that dresses for the Morris-dance were lent out to the neighbouring parishes down to 1629. Some interesting pictures illustrating the usages of bygone ages include the Morris-dance, and gives us a good idea of the costumes of those taking part in it. A painted window at Betley, Staffordshire, has frequently formed the subject of an illustration, and we give one of it.

Here is shown in a spirited style a set of Morris-dancers. It is described in Steven’s “Shakespeare” (Henry IV., Part I.) There are eleven pictures and a Maypole. The characters are as follow: – 1, Robin Hood; 2, Maid Marion; 3, Friar Tuck; 4, 6, 7, 10, and 11, Morris-dancers; 5, the hobby-horse; 8, the Maypole; 9, the piper; and 12, the fool. Figures 10 and 11 have long streamers to the sleeves, and all the dancers have bells, either at the ankles, wrists, or knees. Tollett, the owner of the window, believed it dated back to the time of Henry VIII., c. 1535. Douce thinks it belongs to the reign of Edward IV., and other authorities share his opinion. It is thought that the figures of the English friar, Maypole, and hobby-horse have been added at a later period.

Towards the close of the reign of James I., Vickenboom painted a picture, Richmond Palace, and in it a company of Morris-dancers form an attractive feature. The original painting includes seven figures, consisting of a fool, hobby-horse, piper, Maid Marion, and three dancers. We give an illustration of the first four characters and one of the dancers, from a drawing by Douce, produced from a tracing made by Grose. The bells on the dancer and the fool are clearly shown.

We also present a picture of a Whitsun Morris-dance. In the olden time, at Whitsuntide, this diversion was extremely popular.

Many allusions to the Morris-dancers occur in the writings of Elizabethan authors. Shakespeare, for example, in Henry V., refers to it thus: —

“And let us doit with no show of fear;No! with no more than if we heard that EnglandWere busied with a Whitsun Morris-dance.”In All’s Well that Ends Well, he speaks of the fitness of a “Morris-dance for May-day.” We might cull many quotations from the poets, but we will only make one more and it is from Herrick’s “Hesperides,” describing the blessings of the country: —

“Thy Wakes, thy Quintals, here thou hastThy maypoles, too, with garlands grac’dThy Morris-dance, thy Whitsun-ale;Thy shearing flat, which never fail.”In later times the Morris-dance was frequently introduced on the stage.

As might be expected, the Puritans strongly condemned this form of pleasure. Richard Baxter, in his “Divine Appointment of the Lord’s Day,” gives us a vivid picture of Sunday in a pleasure-loving time. “I have lived in my youth,” says Baxter, “in many places where sometimes shows of uncouth spectacles have been their sports at certain seasons of the year, and sometimes morrice-dancings, and sometimes stage plays and sometimes wakes and revels… And when the people by the book [of Sports] were allowed to play and dance out of public service-time, they could hardly break off their sports that many a time the reader was fain to stay till the piper and players would give over; and sometimes the morrice-dancers would come into the church in all their linen, and scarfs, and antic dresses, with morrice-bells jingling at their legs. And as soon as common prayer was read did haste out presently to their play again.” Stubbes, in his “Anatomie of Abuses” (1585), writes in a similar strain.

The pleasure-loving Stuarts encouraged Sunday sports, and James I., in his Declaration of May 24th 1618, directed that the people should not be debarred from having May-games, Whitsun-ales, and Morris-dances, and the setting up of May poles.

During the Commonwealth, dancing round the Maypole and many other popular amusements were stopped, but no sooner had Charles II. come to the throne of the country than the old sports were revived. For a fuller account of this subject the reader would do well to consult Brand’s “Popular Antiquities,” and the late Alfred Burton’s book on “Rush-Bearing,” from both works we have derived information for this chapter.

The Folk-Lore of Midsummer Eve

The old superstitions and customs of Midsummer Eve form a curious chapter in English folk-lore. Formerly this was a period when the imagination ran riot. On Midsummer Day the Church holds its festival in commemoration of the birth of St. John the Baptist, and some of the old customs relate to this saint.

On the eve of Midsummer Day it was a common practice to light bonfires. This custom, which is a remnant of the old Pagan fire-worship, prevailed in various parts of the country, but perhaps lingered the longest in Cornwall. We gather from Borlase’s “Antiquities of Cornwall,” published in 1754, that at the Midsummer bonfires, the Cornish people attended with lighted torches, tarred and pitched at the end, and made their perambulations round the fires, afterwards going from village to village carrying their torches before them. He regarded the usage as a survival of Druidical superstitions. In the same county it was a practice on St. Stephen’s Down, near Launceston, to erect a tall pole with a bush fixed at the top of it, and round the pole to heap fuel. After the fire was lit, parties of wrestlers contested for prizes specially provided for the festival. According to an old tradition, an evil spirit once appeared in the form of a black dog, and since that time the wrestlers have never been able to meet on Midsummer Eve without being seriously injured in the sport.

About Penzance, not only did the fisher-folk and their friends dance about the blazing fire, but sang songs composed for the joyous time. We give a couple of verses from one of these songs: —

“As I walked out to yonder greenOne evening so fair,All where the fair maids may be seen,Playing at the bonfire.Where larks and linnets sing so sweet,To cheer each lively swain,Let each prove true unto her lover,And so farewell the plain.”Mr. William Bottrell, one of the most painstaking writers on Cornish folk-lore, in an article written in 1873, asserts that not a few old people living in remote and primitive districts, “believe that dancing in a ring over the embers, around a bonfire, or leaping (singly) through its flames, is calculated to insure good luck to the performers, and serve as a protection from witchcraft and other malign influences during the ensuing year.” Mr. Bottrell laments the decay of these pleasing old Midsummer observances. He tells us that within “the memory of many who would not like to be called old, or even aged, on a Midsummer’s eve, long before sunset, groups of girls – both gentle and simple – of from ten to twenty years of age, neatly dressed and decked with garlands, wreaths, or chaplets of flowers, would be seen dancing in the streets.”

Some of the ancient Midsummer rites are still observed in Ireland. We have from an eyewitness some interesting items on the subject. People assemble and dance round fires, the children jump through the flames, and in former times coals were carried into corn fields to prevent blight. The peasants are not, of course, aware that the ceremony is a remnant of the worship of Baal. It is the opinion of not a few that the famous round towers of Ireland were intended for signal fires in connection with this worship.

In the pleasant pages of T. Crofton Croker’s “Researches in the South of Ireland,” are particulars of a custom, observed on the eve of St. John’s Day, of dressing up a broomstick as a figure, and carrying it about in the twilight from one cabin to the other, and suddenly pushing it in at the door, a proceeding which causes both surprise and merriment. The figure is known as Bredogue.

The superstitious inhabitants of the Isle of Man formerly, on Midsummer Eve, lighted fires to the windward side of fields, so that the smoke might pass over the corn. The cattle were folded, and around the animals was carried blazing grass or furze, as a preventative against the influence of witches. Many other strange practices and beliefs prevailed.

In Wales, in the earlier years of the present century, it was customary to fix sprigs of the plant called St. John’s wort over the doors of the cottages, and sometimes over the windows, in order to purify the houses and drive away all fiends and evil spirits. It was the common custom in England in the olden time for people to repair to the woods, break branches from the trees, and carry them to their homes with much delight, and place them over their doors. The ceremony, it is said, was to make good the Scripture prophecy respecting the Baptist, that many should rejoice at his birth.

Midsummer Eve has ever been famous as a time suitable for love divinations, and surely a few notes on love-lore cannot fail to find favour with our fair readers. In a popular story issued at the commencement of this century, from the polished pen of Hannah More, the heroine of the tale says that she would never go to bed on this night without first sticking up in her room the common plant called “Orpine,” or, more generally, “Midsummer Men,” as the bending of the leaves to the right or the left indicate to her if her lover was true or false. The following charming lines refer to the ceremony, and are translated from the German poet, and given in Chambers’s “Book of Days,” so we may infer that the same superstition prevails in that country: —

“The young maid stole through the cottage door,And blushed as she sought the plant of power:‘Thou silver glow-worm, oh, lend me thy light,I must gather the mystic St. John’s wort to-night —The wonderful herb, whose leaf will decideIf the coming year shall make me a bride.’And the glow-worm cameWith its silvery flame,And sparkled and shoneThrough the night of St. John.“And soon as the young maid her love-knot tied,With noiseless tread,To her chamber she sped,Where the sceptral moon her white beams shed:‘Bloom here, bloom here, thou plant of power,To deck the young bride in her bridal hour!’But it droop’d its head, that plant of power,And died the mute death of the voiceless flower;And a wither’d wreath on the ground it lay,More meet for a burial than a bridal day.And when a year was passed away,All pale on her bier the young maid lay;And the glow-worm cameWith its silvery flame,And sparkled and shoneThrough the night of St. John,And they closed the cold grave o’er the maid’s cold clay.”We gather from Thorpe’s “Northern Mythology,” that in Sweden it was the practice to place under the head of a youth or maiden nine kinds of flowers, with a full belief that they would dream of their sweethearts.