полная версия

полная версияNotes on Railroad Accidents

There were two circumstances about this disaster worthy of especial notice. In the first place, as well as can now be ascertained in the absence of any trustworthy record of an investigation into causes, the accident was easily preventable. It appears to have been immediately caused by the derailment of a locomotive, however occasioned, just as it was entering on a swing draw-bridge. Thrown from the tracks, there was nothing in the flooring to prevent the derailed locomotive from deflecting from its course until it toppled over the ends of the ties, nor were the ties and the flooring apparently sufficiently strong to sustain it even while it held to its course. Under such circumstances the derailment of a locomotive upon any bridge can mean only destruction; it meant it then, it means it now; and yet our country is to-day full of bridges constructed in an exactly similar way. To make accidents from this cause, if not impossible at least highly improbable, it is only necessary to make the ties and flooring of all bridges between the tracks and for three feet on either side of them sufficiently strong to sustain the whole weight of a train off the track and in motion, while a third rail, or strong truss of wood, securely fastened, should be laid down midway between the rails throughout the entire length of the bridge and its approaches. With this arrangement, as the flanges of the wheels are on the inside, it must follow that in case of derailment and a divergence to one side or the other of the bridge, the inner side of the flange will come against the central rail or truss just so soon as the divergence amounts to half the space between the rails, which in the ordinary gauge is two feet and four inches. The wheels must then glide along this guard, holding the train from any further divergence from its course, until it can be checked. Meanwhile, as the ties and flooring extend for the space of three feet outside of the track, a sufficient support is furnished by them for the other wheels. A legislative enactment compelling the construction of all bridges in this way, coupled with additional provisions for interlocking of draws with their signals in cases of bridges across navigable waters, would be open to objection that laws against dangers of accident by rail have almost invariably proved ineffective when they were not absurd, but in itself, if enforced, it might not improbably render disasters like those at Norwalk and Des Jardines terrors of the past.

CHAPTER XIII.

CAR-COUPLINGS IN DERAILMENTS

Wholly apart from the derailment, which was the real occasion of the Des Jardines disaster, there was one other cause which largely contributed to its fatality, if indeed that fatality was not in greatest part immediately due to it.

The question as to what is the best method of coupling together the several individual vehicles which make up every railroad train has always been much discussed among railroad mechanics. The decided weight of opinion has been in favor of the strongest and closest couplings, so that under no circumstances should the train separate into parts. Taking all forms of railroad accident together, this conclusion is probably sound. It is, however, at best only a balancing of disadvantages, – a mere question as to which practice involves the least amount of danger. Yet a very terrible demonstration that there are two sides to this as to most other questions was furnished at Des Jardines. It was the custom on the Great Western road not only to couple the cars together in the method then in general use, but also, as is often done now, to connect them by heavy chains on each side of the centre coupling. Accordingly when the locomotive broke through the Des Jardines bridge, it dragged the rest of the train hopelessly after it. This certainly would not have happened had the modern self-coupler been in use, and probably would not have happened had the cars been connected only by the ordinary link and pins; for the train was going very slowly, and the signal for brakes was given in ample time to apply them vigorously before the last cars came to the opening, into which they were finally dragged by the dead weight before them and not hurried by their own momentum.

On the other hand, we have not far to go in search of scarcely less fatal disasters illustrating with equal force the other side of the proposition, in the terrible consequences which have ensued from the separation of cars in cases of derailment. Take, for instance, the memorable accident of June 17, 1858, near Port Jervis, on the Erie railway.

As the express train from New York was running at a speed of about thirty miles an hour over a perfectly straight piece of track between Otisville and Port Jervis, shortly after dark on the evening of that day, it encountered a broken rail. The train was made up of a locomotive, two baggage cars and five passenger cars, all of which except the last passed safely over the fractured rail. The last car was apparently derailed, and drew the car before it off the track. These two cars were then dragged along, swaying fearfully from side to side, for a distance of some four hundred feet, when the couplings at last snapped and they went over the embankment, which was there some thirty feet in height. As they rushed down the slope the last car turned fairly over, resting finally on its roof, while one of its heavy iron trucks broke through and fell upon the passengers beneath, killing and maiming them. The other car, more fortunate, rested at last upon its side on a pile of stones at the foot of the embankment. Six persons were killed and fifty severely injured; all of the former in the last car.

In this case, had the couplings held, the derailed cars would not have gone over the embankment and but slight injuries would have been sustained. Modern improvements have, however, created safeguards sufficient to prevent the recurrence of other accidents under the same conditions as that at Port Jervis. The difficulty lay in the inability to stop a train, though moving at only moderate speed, within a reasonable time. The wretched inefficiency of the old hand-brake in a sudden emergency received one more illustration. The train seems to have run nearly half a mile after the accident took place before it could be stopped, although the engineer had instant notice of it and reversed his locomotive. The couplings did not snap until a distance had been traversed in which the modern train-brake would have reduced the speed to a point at which they would have been subjected to no dangerous strain.

The accident ten years later at Carr's Rock, sixteen miles west of Port Jervis, on the same road, was again very similar to the one just described: and yet in this case the parting of the couplings alone prevented the rear of the train from dragging its head to destruction. Both disasters were occasioned by broken rails; but, while the first occurred on a tangent, the last was at a point where the road skirted the hills, by a sharp curve, upon the outer side of which was a steep declivity of some eighty feet, jagged with rock and bowlders. It befell the night express on the 14th of April, 1876. The train was a long one, consisting of the locomotive, three baggage and express, and seven passenger cars, and it encountered the broken rail while rounding the curve at a high rate of speed. Again all except the last car, passed over the fracture in safety; this was snapped, as it were, off the track and over the embankment. At first it was dragged along, but only for a short distance; the intense strain then broke the coupling between the four rear cars and the head of the train, and, the last of the four being already over the embankment, the others almost instantly toppled over after it and rolled down the ravine. A passenger on this portion of the train, described the car he was in "as going over and over, until the outer roof was torn off, the sides fell out, and the inner roof was crushed in." Twenty-four persons were killed and eighty injured; but in this instance, as in that at Des Jardines, the only occasion for surprise was that there were any survivors.

Accidents arising from the parting of defective couplings have of course not been uncommon, and they constitute one of the greatest dangers incident to heavy gradients; in surmounting inclines freight trains will, it is found, break in two, and their hinder parts come thundering down the grade, as was seen at Abergele. The American passenger trains, in which each car is provided with brakes, are much less liable than the English, the speed of which is regulated by brake-vans, to accidents of this description. Indeed, it may be questioned whether in America any serious disaster has occurred from the fact that a portion of a passenger train on a road operated by steam got beyond control in descending an incline. There have been, however, terrible catastrophes from this cause in England, and that on the Lancashire & Yorkshire road near Helmshere, a station some fourteen miles north of Manchester, deserves a prominent place in the record of railroad accidents.

It occurred in the early hours of the morning of the 4th of September, 1860. There had been a great fête at the Bellevue Gardens in Manchester on the 3d, upon the conclusion of which some twenty-five hundred persons crowded at once upon the return trains. Of these there were, on the Lancashire & Yorkshire road, three; the first consisting of fourteen, the second of thirty-one, and the last of twenty-four carriages: and they were started, with intervals of ten minutes between them, at about eleven o'clock at night. The first train finished its journey in safety. Not so the second and the third. The Helmshere station is at the top of a steep incline. This the second train, drawn by two locomotives, surmounted, and then stopped for the delivery of passengers. While these were leaving the carriages, a snap as of fractured iron was heard, and the guards, looking back, saw the whole rear portion of the train, consisting of seventeen carriages and a brake-van, detached from the rest of it and quietly slipping down the incline. The detached portion was moving so slowly that one of the guards succeeded in catching the van and applying the brakes; it was, however, already too late. The velocity was greater than the brake-power could overcome, and the seventeen carriages kept descending more and more rapidly. Meanwhile the third train had reached the foot of the incline and begun to ascend it, when its engineer, on rounding a curve, caught sight of the descending carriages. He immediately reversed his engine, but before he could bring his train to a stand they were upon him. Fortunately the van-brakes of the detached carriages, though insufficient to stop them, yet did reduce their speed; the collision nevertheless was terrific. The force of the blow, so far as the advancing train was concerned, expended itself on the locomotive, which was demolished, while the passengers escaped with a fright. Not so those in the descending carriages. With them there was nothing to break the blow, and the two hindmost carriages were crushed to fragments and their passengers scattered over the line. It was shortly after midnight, and the excursionists clambered out of the trains and rushed frantically about, impeding every effort to clear away the débris and rescue the injured, whose shrieks and cries were incessant. The bodies of ten persons, one of whom had died of suffocation, were ultimately taken out from the wreck, and twenty-two others sustained fractures of limbs.

At Des Jardines the couplings were too strong; at Port Jervis and at Helmshere they were not strong enough; at Carr's Rock they gave way not a moment too soon. "There are objections to a plenum and there are objections to a vacuum," as Dr. Johnson remarked, "but a plenum or a vacuum it must be." There are no arguments, however, in favor of putting railroad stations or sidings upon an inclined plane, and then not providing what the English call "catch-points" or "scotches" to prevent such disasters as those at Abergele or Helmshere. In these two instances alone the want of them cost over fifty lives. In railroad mechanics there are after all some principles susceptible of demonstration. That vehicles, as well as water, will run down hill may be classed among them. That these principles should still be ignored is hardly less singular than it is surprising.

CHAPTER XIV.

THE REVERE CATASTROPHE

The terrible disaster which occurred in front of the little station-building at Revere, six miles from Boston on the Eastern railroad of Massachusetts, in August 1871, was, properly speaking, not an accident at all; it was essentially a catastrophe – the legitimate and almost inevitable final outcome of an antiquated and insufficient system. As such it should long remain a subject for prayerful meditation to all those who may at any time be entrusted with the immediate operating of railroads. It was terribly dramatic, but it was also frightfully instructive; and while the lesson was by no means lost, it yet admits of further and advantageous study. For, like most other men whose lives are devoted to a special calling, the managers of railroads are apt to be very much wedded to their own methods, and attention has already more than once been called to the fact that, when any new emergency necessitates a new appliance, they not infrequently, as Captain Tyler well put it in his report to the Board of Trade for the year 1870, "display more ingenuity in finding objections than in overcoming them."

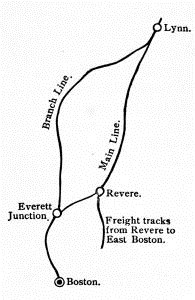

The Eastern railroad of Massachusetts connects Boston with Portland, in the state of Maine, by a line which is located close along the sea-shore. Between Boston and Lynn, a distance of eleven miles, the main road is in large part built across the salt marshes, but there is a branch which leaves it at Everett, a small station some miles out of Boston, and thence, running deviously through a succession of towns on the higher ground, connects with the main track again at Lynn; thus making what is known in England as a loop-road. At the time of the Revere accident this branch was equipped with but a single track, and was operated wholly by schedule without any reliance on the telegraph; and, indeed, there were not even telegraphic offices at a number of the stations upon it. Revere, the name of the station where the accident took place, was on the main line about five miles from Boston and two miles from Everett, where the Saugus branch, as the loop-road was called, began. The accompanying diagram shows the relative position of the several points and of the main and branch lines, a thorough appreciation of which is essential to a correct understanding of the disaster.

The travel over the Eastern railroad is of a somewhat exceptional nature, varying in a more than ordinary degree with the different seasons of the year. During the winter months the corporation had, in 1871, to provide for a regular passenger movement of about seventy-five thousand a week, but in the summer what is known as the excursion and pleasure travel not infrequently increased the number to one hundred and ten thousand, and even more. As a natural consequence, during certain weeks of each summer, and more especially towards the close of August, it was no unusual thing for the corporation to find itself taxed beyond its utmost resources. It is emergencies of this description, periodically occurring on every railroad, which always subject to the final test the organization and discipline of companies and the capacity of superintendents. A railroad in quiet times is like a ship in steady weather; almost anybody can manage the one or sail the other. It is the sudden stress which reveals the undeveloped strength or the hidden weakness; and the truly instructive feature in the Revere accident lay in the amount of hidden weakness everywhere which was brought to light under that sudden stress. During the week ending with that Saturday evening upon which the disaster occurred the rolling stock of the road had been heavily taxed, not only to accommodate the usual tide of summer travel, then at its full flood, but also those attending a military muster and two large camp-meetings upon its line. The number of passengers going over it had accordingly risen from about one hundred and ten thousand, the full summer average, to over one hundred and forty thousand; while instead of the one hundred and fifty-two trains a day provided for in the running schedule, there were no less than one hundred and ninety-two. It had never been the custom with those managing the road to place any reliance upon the telegraph in directing the train movement, and no use whatever appears to have been made of it towards straightening out the numerous hitches inevitable from so sudden an increase in that movement. If an engine broke down, or a train got off the track, there had accordingly throughout that week been nothing done, except patient and general waiting, until things got in motion again; each conductor or station-master had to look out for himself, under the running regulations of the road, and need expect no assistance from headquarters. This, too, in spite of the fact that, including the Saugus branch, no less than ninety-three of the entire one hundred and fifteen miles of road operated by the company were supplied only with a single track. The whole train movement, both of the main line and of the branches, intricate in the extreme as it was, thus depended solely on a schedule arrangement and the watchful intelligence of individual employés. Not unnaturally, therefore, as the week drew to a close the confusion became so great that the trains reached and left the Boston station with an almost total disregard of the schedule; while towards the evening of Saturday the employés of the road at that station directed their efforts almost exclusively to dispatching trains as fast as cars could be procured, thus trying to keep it as clear as possible of the throng of impatient travellers which continually blocked it up. Taken altogether the situation illustrated in a very striking manner that singular reliance of the corporation on the individuality and intelligence of its employés, which in another connection is referred to as one of the most striking characteristics of American railroad management, without a full appreciation of which it is impossible to understand its using or failing to use certain appliances.

According to the regular schedule four trains should have left the Boston station in succession during the hour and a half between 6.30 and eight o'clock P.M.: a Saugus branch train for Lynn at 6.30; a second Saugus branch train at seven; an accommodation train, which ran eighteen miles over the main line, at 7.15; and finally the express train through to Portland, also over the main line, at eight o'clock. The collision at Revere was between these last two trains, the express overtaking and running into the rear of the accommodation train; but it was indirectly caused by the delays and irregularity in movement of the two branch trains. It will be noticed that, according to the schedule, both of the branch trains should have preceded the accommodation train; in the prevailing confusion, however, the first of the two branch trains did not leave the station until about seven o'clock, thirty minutes behind its time, and it was followed forty minutes later, not by the second branch train, but by the accommodation train, which in its turn was twenty-five minutes late. Thirteen minutes afterwards the second Saugus branch train, which should have preceded, followed it, being nearly an hour out of time. Then at last came the Portland express, which got away practically on time, at a few minutes after eight o'clock. All of these four trains went out over the same track as far as the junction at Everett, but at that point the first and third of the four were to go off on the branch, while the second and fourth kept on over the main line. Between these last two trains the running schedule of the road allowed an ample time-interval of forty-five minutes, which, however, on this occasion was reduced, through the delay in starting, to some fifteen or twenty minutes. No causes of further delay, therefore, arising, the simple case was presented of a slow accommodation train being sent out to run eighteen miles in advance of a fast express train, with an interval of twenty minutes between them.

Unfortunately, however, the accommodation train was speedily subjected to another and very serious delay. It has been mentioned that the Saugus branch was a single track road, and the rules of the company were explicit that no outward train was to pass onto the branch at Everett until any inward train then due there should have arrived and passed off it. There was no siding at the junction, upon which an outward branch train could be temporarily placed to wait for the inward train, thus leaving the main track clear; and accordingly, under a strict construction of the rules, any outward branch train while awaiting the arrival at Everett of an inward branch train was to be kept standing on the main track, completely blocking it. The outward branch trains, it subsequently appeared, were often delayed at the junction, but no practical difficulty had arisen from this cause, as the employé in charge of the signals and switches there, exercising his common sense, had been in the custom of moving any delayed train temporarily out of the way onto the branch or the other main track, under protection of a flag, and thus relieving the block. The need of a siding to permit the passage of trains at this point had not been felt, simply because the employé in charge there had used the branch or other main track as a siding. On the day of the accident this employé happened to be sick, and absent from his post. His substitute either had no common sense or did not feel called upon to use it, if its use involved any increase of responsibility. Accordingly, when a block took place, the simple letter of the rule was followed; – and it is almost needless to add that a block did take place on the afternoon of August 26th.

The first of the branch trains, it will be remembered, had left Boston at about seven o'clock, instead of at 6.30, its schedule time. On arriving at Everett this train should have met and passed an inward branch train, which was timed to leave Lynn at six o'clock, but which, owing to some accident to its locomotive, and partaking of the general confusion of the day, on this particular afternoon did not leave the Lynn station until 7.30 o'clock, or one hour and a half after its schedule time, and one half-hour after the other train had left Boston. Accordingly, when the Boston train reached the junction its conductor found himself confronted by the rule forbidding him to enter upon the branch until the Lynn train then due should have passed off it, and so he quietly waited on the outward track of the main line, blocking it completely to traffic. He had not waited long before a special locomotive, on its way from Boston to Salem, came up and stopped behind him. This was presently followed by the accommodation train. Then the next branch train came along, and finally the Portland express. At such a time, and at that period of railroad development, there was something ludicrous about the spectacle. Here was a road utterly unable to accommodate its passengers with cars, while a succession of trains were standing idle for hours, because a locomotive had broken down ten miles off. The telegraph was there, but the company was not in the custom of putting any reliance upon it. A simple message to the branch trains to meet and pass at any point other than that fixed in the schedule would have solved the whole difficulty; but, no! – there were the rules, and all the rolling stock of the road might gather at Everett in solemn procession, but, until the locomotive at Lynn could be repaired, the law of the Medes and Persians was plain; and in this case it read that the telegraph was a new-fangled and unreliable auxiliary. And so the lengthening procession stood there long enough for the train which caused it to have gone to its destination and come back dragging the disabled locomotive from Lynn behind it to again take its place in the block.

At last, at about ten minutes after eight o'clock, the long-expected Lynn train made its appearance, and the first of the branch trains from Boston immediately went off the main line. The road was now clear for the accommodation train, which had been standing some twelve or fifteen minutes in the block, but which from the moment of again starting was running on the schedule time of the Portland express. This its conductor did not know. Every minute was vital, and yet he never thought to look at his watch. He had a vague impression that he had been delayed some six or eight minutes, when in reality he had been delayed fifteen; and, though he was running wholly out of his schedule time, he took not a single precaution, so persuaded was he that every one knew where he was.