полная версия

полная версияNotes on Railroad Accidents

To obviate these defects Westinghouse in 1872 invented what he termed a triple valve attachment, by means of which, if the thing can be so expressed, his brake was made to always stand at danger. That is, in case of any derangement of its parts, it was automatically applied and the train stopped. The action of the brake was thus made to give notice of anything wrong anywhere in the train. A noticeable case of this occurred on the Midland railway in England, when on the November 22, 1876, as the Scotch express was approaching the Heeley station, at a speed of some sixty miles an hour, the hind-guard felt the automatic brake suddenly self-applied. The forward truck of a Pullman car in the middle of the train had left the rails; the front part of the train broke the couplings and went on, while the rear carriages, acted upon by the automatic brakes, came to a stand immediately behind the Pullman, which finally rested on its side across the opposite track. There was no loss of life. On the other hand, as the Scotch express on the North Eastern road was approaching Morpeth, on March 25, 1877, at a speed of some twenty-five miles an hour, the locomotive for some reason left the track. The train was not equipped with an automatic brake, and the carriages in it accordingly pressed forward upon each other until three of them were so utterly destroyed as to be indistinguishable. Five passengers lost their lives; the remains of one of whom, together with the wheels of a carriage, were afterwards taken out from the tank of the tender, into which they had been driven by the force of the shock.

The theoretical objection to the automatic brake is obvious. In case of any derangement of its machinery it applies itself, and, should these derangements be of frequent occurrence, the consequent stoppage of trains would prove a great annoyance, if not a source of serious danger. This objection is not sustained by practical experience. The triple valve, so called, is the only complicated portion of the automatic brake, and this valve is well protected and not liable to get out of order.24 Should it become deranged it will stop the working of the brake on that car alone to which it belongs; and it will become deranged so as to set the brake only from causes which would render the non-automatic brake inoperative. When anything of this sort occurs, it stops the train until the defect is remedied. The returns made to the English Board of Trade enable us to know just how frequently in actual and regular service these stoppages occur, and what they amount to. Take, for instance, the North Eastern and the Caledonian railways. Both use the automatic brake. During the last six months of 1878 the first ran 138,000 train miles with it, in the course of which there were eight delays or stoppages of some three to five minutes each occasioned by the action of the triple-valve; being in round numbers one occasion of delay in 17,000 miles of train movement. On the Caledonian railway, during the same period, four brake failures, due to the action of the triple-valve, were reported in runs aggregating over 62,000 miles, being about one failure to 15,000 miles. These failures moreover occasioned delays of only a few minutes each, and, where the cause of the difficulty was not so immediately apparent that it could at once be remedied, the brake-tubes of the vehicle on which the difficulty occurred were disconnected, and the trains went on.25 One of these stoppages, however, resulted in a serious accident. As a train on the Caledonian road was approaching the Wemyss Bay junction on December 14th, in a dense fog, the engine driver, seeing the signals at danger, undertook to apply his brake slightly, when it went full on, stopping the train between the distant and home signals, as they are called in the English block system. After the danger signal was lowered, but before the brake could be released, the signal-man allowed a following train to enter upon the same block section, and a collision followed in which some thirteen passengers were slightly injured. This accident, however, as the inspecting officer of the Board of Trade very properly found, was due not at all to the automatic brake, but to "carelessness on the part of the signal-man, who disregarded the rules for the working of the block telegraph instruments," and to the driver of the colliding train, who "disobeyed the company's running regulations." It gives an American, however, a realizing sense of one of the difficulties under which those crowded British lines are operated, to read that in this case the fog was "so thick that the tail-lamp was not visible from an approaching train for more than a few yards."

After the application of the triple valve had made it automatic, there remained but one further improvement necessary to render the Westinghouse a well-nigh perfect brake. A superabundance of self-acting power had been secured, but no provision was yet made for graduating the use of that power so that it should be applied in the exact degree, neither more nor less, which would soonest stop the train. This for two reasons is mechanically a matter of no little importance. As is well known a too severe application of brakes, no matter of what kind they are, causes the wheels to stand still and slide upon the rails. This is not only very injurious to rolling stock, the wheels of which are flattened at the points which slide, but, as has long been practically well-known to those whose business it is to run locomotives, when once the wheels begin to slide the retarding power of the brakes is seriously diminished. In order, therefore, to secure the maximum of retarding power, the pressure of the brake-blocks on the revolving wheels should be very great when first applied, and just sufficient not to slide them; and should then be diminished, pari passu with the momentum of the train, until it wholly stops. Familiar as all this has long been to engine-drivers and practical railroad mechanics, yet it has not been conceded in the results of many scientific inquiries. In the report of one of the Royal Commissions on Accidents, for instance, it was asserted that the momentum of a train was retarded more by the action of sliding than of slowly revolving wheels; and again, as recently as in May, 1877, in a scientific discussion in London at one of the meetings of the Society of Arts, a gentleman, with the letters C. E. appended to his name, ventured the surprising assertion that "no brake could do more than skid the wheels of a train, and all continuous brakes professed to do this, and he believed did so about equally well." Now, what it is here asserted no brake can do is exactly what the perfect brake will be made to do, – and what Westinghouse's latest improvement, it is claimed, enables his brake to do. It much more than "skids the wheels," by measuring out exactly that degree of power necessary to hold the wheels just short of the skidding point, and in this way always exerts the maximum retarding force. This is brought about by means of a contrivance which allows the air to leak out of the brake cylinders so as to exactly proportion the pressure of the blocks on the wheels to the speed with which the latter are revolving. In other, and more scientific, language the force with which the brake-blocks are pressed upon the wheels is made to adjust itself automatically as the "coefficient of dynamic friction augments with the reduction of train speed." It hardly needs to be said that in this way the power of the brake is enormously increased.

In America the superiority of the Westinghouse over any other description of train-brake has long been established through that large preponderance of use which in such matters constitutes the final and irreversible verdict.26 In Europe, however, and especially in Great Britain, ever since the Shipton-on-Cherwell accident in 1874, the battle of the brakes, as it may not inappropriately be called, has waxed hotter and hotter; and not only has this battle been extremely interesting in a scientific way, but it has been highly characteristic, and at times enlivened by touches of human nature which were exceedingly amusing.

CHAPTER XX.

THE BATTLE OF THE BRAKES

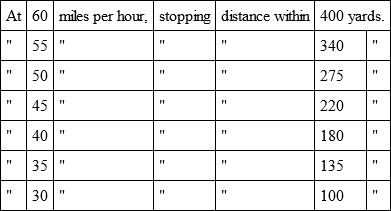

The English battle of the brakes may be said to have fairly opened with the official report from Captain Tyler on the Shipton accident, in reference to which he expressed the opinion, which has already been quoted in describing the accident, that "if the train had been fitted with continuous brakes throughout its whole length there is no reason why it should not have been brought to rest without any casuality." The Royal Commission on railroad accidents then took the matter up and called for a series of scientifically conducted experiments. These took place under the supervision of two engineers appointed by the Commission, who were aided by a detail of officers and men from the royal engineers. Eight brakes competed, and a train, consisting of a locomotive and thirteen cars, was specially prepared for each. With these trains some seventy runs were made, and their results recorded and tabulated; the experiments were continued through six consecutive working days. Of the brakes experimented with three were American in their origin, – Westinghouse's automatic and vacuum, and Smith's vacuum. The remainder were English, and were steam, hydraulic, and air brakes; among them also was one simple emergency brake. The result of the trials was a very decided victory for the Westinghouse automatic, and upon its performances the Commission based its conclusion that trains ought to be so equipped that in cases of emergency they could be brought to rest, when travelling on level ground at 50 miles an hour, within a distance of 275 yards; with an allowance of distance in cases of speed greater or less than 50 miles nearly proportioned to its square. These allowances they tabulated as follows: —

To appreciate the enormous advance in what may be called stopping power which these experiments revealed, it should be added that the first series of experiments made at Newark were with trains equipped only with the hand-brake. The average speed in these experiments was 47 miles, and with the train-brake, according to the foregoing tabulation, the stop should have been made in about 250 yards; in reality it was made in a little less than five times that distance, or 1120 yards; in other words the experiments showed that the improved appliances had more than quadrupled the control over trains. It has already been noticed that in the cases of the Angola and the Port Jervis disasters, as well as in that at Shipton, the trains ran some 2,700 feet before they could be stopped. Under the English tabulations above given, in the results of which certain recent improvements do not enter, a train running into the 42d Street Station in New York, at a speed of forty-five miles an hour when under the entrance arches, would be stopped before it reached the buffers at the end of the covered tracks.

The Royal Commission experiments were followed in May and June, 1877, by yet others set on foot by the North Eastern Railway Company for the purpose of making a competitive test of the Westinghouse automatic and the Smith's vacuum brakes. At this trial also the average stop at a speed of 50 miles an hour was effected in 15 seconds, and within a distance of 650 feet. Other series of experiments with similar results were, about the same time, conducted under the auspices of the Belgian and German governments, of which elaborate official reports were made. The result was that at last, under date of August 30, 1877, the Board of Trade issued a circular to the railway companies in which it called attention to the fact that, notwithstanding all the discussion which had taken place and the elaborate official trials which the government had set on foot, there had "apparently been no attempt on the part of the various companies to take the first step of agreeing upon what are the requirements which, in their opinion, are essential to a good continuous brake." In other words, the Board found that, instead of becoming better, matters were rapidly becoming worse. Each company was equipping its rolling stock with that appliance in which its officers happened to be interested as owners or inventors, and when carriages thus equipped passed from the tracks of one road onto those of another the result was a return to the old hand-brake system in a condition of impaired efficiency. The Board accordingly now proceeded to narrow down the field of selection by specifying the following as what it considered the essentials of a good continuous brake: —

a. "The brakes to be efficient in stopping trains, instantaneous in their actions, and capable of being applied without difficulty by engine-drivers or guards.

b. "In case of accident, to be instantaneously self-acting.

c. "The brakes to be put on and taken off (with facility) on the engine and on every vehicle of a train.

d. "The brakes to be regularly used in daily working.

e. "The materials employed to be of a durable character, so as to be easily maintained and kept in order."

These requirements pointed about as directly as they could to the Westinghouse, to the exclusion of all competing brakes. Not more than one other complied with them in all respects, and many made no pretence of complying at all. Then followed what may be termed the battle royal of the brakes, which as yet shows no signs of drawing to a close. As the avowed object of the Board of Trade was to introduce, one brake, to the necessary exclusion of all others, throughout the railroad system of Great Britain, the magnitude of the prize was not easy to over-estimate. The weight of scientific and official authority was decidedly in favor of the Westinghouse automatic, but among the railroad men the Smith vacuum found the largest number of adherents. It failed to meet three of the requirements of the Board of Trade, in that it was neither automatic nor instantaneous in its action, while the materials employed in it were not of a durable character. It was, on the other hand, a brake of unquestioned excellence, while it commended itself to the judgment of the average railroad official by its simplicity, and to that of the average railroad director by its apparent cheapness. Any one could understand it, and its first cost was temptingly small. The real struggle in Great Britain, therefore, has been, and now is, between these two brakes; and the fact that both of them are American has been made to enter largely into it, and in a way also which at times lent to the discussion an element of broad humor.

For instance, the energetic agent of the Smith vacuum, feeling himself aggrieved by some statement which appeared in the Times, responded thereto in a circular, in the composition of which he certainly evinced more zeal than either judgment or literary skill. This circular and its author were then referred to by the editors of Engineering, a London scientific journal, in the following slightly de haut en bas style: —

"It is not a little remarkable, and it is a fact not harmonious with the feelings of English engineers, that the two brakes recommending themselves for adoption are of American origin. * * * Now we cannot wonder, considering what our past experience has been in many of our dealings with Americans, that this feeling of distrust and prejudice exists. It is not merely sentimental, it is founded on many and untoward and costly experiences of the past, and the fear of similar experiences in the future. And when we see the representative of one of these systems adopting the traditional policy of his country, and meeting criticism with abuse – abuse of men pre-eminent in the profession, and journals which he apparently forgets are neither American nor venal – we do not wonder that our railway engineers feel a repugnance to commit themselves."

The superiority of the British over the American controversialist, as respects courtesy and restraint in language, being thus satisfactorily established, it only remained to illustrate it. This, however, had already been done in the previous May; for at that time it chanced that Captain Tyler, having retired from his position at the head of the railway inspectors department of the Board of Trade, was considering an offer which Mr. Westinghouse had made him to associate himself with the company owning the brakes known by that name. Before accepting this offer, Captain Tyler took advantage of a meeting of the Society of Arts to publicly give notice that he was considering it. This he did in a really admirable paper on the whole subject of continuous brakes, at the close of which a general discussion was invited and took place, and in the course of it the innate superiority of the British over any other kind of controversialist, so far at least as courtesy and a delicate refraining from imputations is concerned, received pointed illustration.

No sooner had Captain Tyler finished than Mr. Houghton, C. E., took occasion to refer to the paper he had read as "an elaborate puff to the Westinghouse brake, with which he [Tyler] was, as he told, connected, or about to be." Subsequently Mr. Steele proceeded to say that: —

"On receiving the invitation to be present at the meeting, he had been somewhat afraid that Captain Tyler was going to lose his fine character for impartiality by throwing in his lot with the brake-tinkers, but it came out that not only was he going to do that, but actually going to be a partner in a concern. * * * The speaker then proceeded to discuss the Westinghouse brake, which he called the Westinghouse and Tyler brake, designating it as a jack-in-the-box, a rattle trap, to please and decoy, and not an invention at all. No engineer had a hand in its manufacture. It was the discovery of some Philadelphia barber or some such thing. He had spoken of honest brakes. This was a brake which had all sorts of pretensions. It had not worked well, but whenever there was any row about its not working well, they got the papers to praise it up, and that was how the papers were under the thumb, and would not speak of any other. * * * He thought it would not do for railway companies to take a bad brake, and Captain Tyler and Mr. Westinghouse be able to make their fortunes by floating a limited company for its introduction. They had heard of Emma mines and Lisbon tramways, and such like, and he felt it would not be well to stand by and allow this to be done."

All of which was not only to the point, but finely calculated to show the American inventors and agents who were present the nice and mutually respectful manner in which such discussions were carried on by all Englishmen.

Though the avowed adhesion of Sir Henry Tyler to the Westinghouse was a most important move in the war of the brakes, it did not prove a decisive one. The complete control of the field was too valuable a property to be yielded in deference to that, or any other name without a struggle; and, so to speak, there were altogether too many ins and outs to the conflict. Back door influences had everywhere to be encountered. The North Western, for instance, is the most important of the railway companies of the United Kingdom. The locomotive superintendent of that company was the part inventor and proprietor of an emergency brake which had been extensively adopted by it on its rolling stock, but which wholly failed to meet the requirements laid down in its circular by the Board of Trade. Immediately after issuing that circular the Board of Trade called the attention of the company to this fact in connection with an accident which had recently occurred, and in very emphatic language pointed out that the brakes in question could not "in any reasonable sense of the word be called continuous brakes," and that it was clear that the circular requirements were "not complied with by the brake-system of the London & North Western Railway Company;" in case that company persisted in the use of that brake, the secretary of the Board went on to say, "in the event of a casualty occurring, which an efficient system of brakes might have prevented, a heavy personal responsibility will rest upon those who are answerable for such neglect." This was certainly language tolerably direct in its import. As such it was calculated to cause those to whom it was addressed to pause in their action. The company, however, treated it with a superb disregard, all the more contemptuous because veiled in language of deferential civility. They then quietly went on applying their locomotive superintendent's emergency brake to their equipment, until on the 30th of June, 1879, they returned no less than 2,052 carriages fitted with it; that being by far the largest number returned by any one company in the United Kingdom.

A more direct challenge to the Board of Trade and to Parliament could not easily have been devised. To appreciate how direct it was, it is necessary to bear in mind that in its circular of August 30, 1877, in which the requirements of a satisfactory train-brake were laid down, the Board of Trade threw out to the companies the very significant hint, that they "would do well to reflect that if a doubt should arise that from a conflict of interest or opinion, or from any other cause, they [the companies] are not exerting themselves, it is obvious that they will call down upon themselves an interference which the Board of Trade, no less than the companies, desire to avoid." In his general report on the accidents of the year 1877, the successor of Captain Tyler expressed the opinion that "sufficient information and experience would now appear to be available, and the time is approaching when the railway companies may fairly be expected to come to a decision as to which of the systems of continuous brakes is best calculated to fulfil the requisite conditions, and is most worthy of general adoption." At the close of another year, however, the official returns seemed to indicate that, while but a sixth part of the passenger locomotives and a fifth part of the carriages in use on the railroads of the United Kingdom were yet equipped with continuous brakes at all, a concurrence of opinion in favor of any one system was more remote than ever. During the six months ending December 31, 1878, but 127 additional locomotives out of about 4000, and 1,200 additional carriages out of some 32,000 were equipped; of which 70 locomotives and 530 carriages had been equipped with the Smith vacuum, which in three most important respects failed to comply with the Board of Trade requirements. Under these circumstances the Board of Trade was obviously called upon either to withdraw from the position it had taken, or to invite that "interference" in its support to which in its circular of August, 1877 it had so portentously referred. It decided to do the latter, and in March, 1879 the government gave an intimation in the House of Lords that early Parliamentary action was contemplated. As it is expressed, the railway companies are to "be relieved of their indecision."

In Great Britain, therefore, the long battle of the brakes would seem to be drawing to its close. The final struggle, however, will be a spirited one, and one which Americans will watch with considerable interest, – for it is in fact a struggle between two American brakes, the Westinghouse and the Smith vacuum. Of the 907 locomotives hitherto equipped with the continuous brakes no less than 819 are equipped with one or the other of these American patents, besides over 4,464 of the 9,919 passenger carriages. The remaining 3,857 locomotives and 30,000 carriages are the prize of victory. As the score now stands the vacuum brake is in almost exactly twice the use of its more scientific rival. The weight of authority and experience, and the requirements of the Board of Trade, are, however, on the opposite side.

As deduced from the European scientific tests and the official returns, the balance of advantages would seem to be as follows: – In favor of the vacuum are its superficial simplicity, and possible economy in first cost: – In favor of the Westinghouse automatic are its superior quickness in application, the greater rapidity in its stopping power, the more durable nature of its materials, the smaller cost in renewal, its less liability to derangement, and above all its self-acting adjustment. The last is the point upon which the final issue of the struggle must probably turn. The use of any train-brake which is not automatic in its action, as has already been pointed out, involves in the long run disaster, – and ultimate serious disaster. The mere fact that the brake is generally so reliable, – that ninety-nine times out of the hundred it works perfectly, – simply makes disaster certain by the fatal confidence it inspires. Ninety-nine times in a hundred the brake proves reliable; – nine times in the remaining ten of the thousand, in which it fails, a lucky chance averts disaster; – but the thousandth time will assuredly come, as it did at Communipaw and on the New York Elevated railway, and, much the worst of all yet, at Wollaston. Soon or late the use of non-automatic continuous brakes will most assuredly, if they are not sooner abandoned, be put an end to by the occurrence of some not-to-be forgotten catastrophe of the first magnitude, distinctly traceable to that cause. Meanwhile that automatic brakes are complicated and sometimes cause inconvenience in their operation is most indisputable. This is an objection, also, to which they are open in common with most of the riper results of human ingenuity; – but, though sun-dials are charmingly simple, we do not, therefore, discard chronometers in their favor; neither do we insist on cutting our harvests with the scythe, because every man who may be called upon to drive a mowing machine may not know how to put one together. But what Sir Henry Tyler has said in respect to this oldest and most fallacious, as well as most wearisome, of objections covers the whole ground and cannot be improved upon. After referring to the fact that simplicity in construction and simplicity in working were two different things, and that, almost invariably, a certain degree of complication in construction is necessary to secure simplicity in working, – after pointing this out he went on to add that, —