полная версия

полная версияAlcohol: A Dangerous and Unnecessary Medicine, How and Why

“Experience teaches that true science does not antagonize nature. In surgical cases, in septicæmia, in pneumonia, or in any of the fevers, water freely administered has proven to be a real source of comfort, and an aid to recovery. It is amazing how favorably diseases terminate under this beneficent beverage. The withholding of food does not retard, but rather hastens convalescence.

“In the conduct of our Red Cross patients, irrespective of their condition when admitted, it can be truly said that after treatment began, delirium has not been witnessed in a single instance, and as our hospital reports indicate, our mortality has been unusually small.

“Alcohol has not figured as a life-saver in our institution. Cases of extreme collapse following major operations, cases of pneumonia, where the pulse ranged from 160 to 220, patients suffering from pernicious anæmia, septicæmia, pyæmia, cholera infantum and typhoid fever, some of whom when first seen were in the worst stages of delirium and collapse have without alcohol regained consciousness, overcome delirium and made excellent recoveries.

“The following cases very forcibly illustrate the results of non-alcoholic treatment: —

“Case No. 1. A child, aged nine months, under treatment for six days for pneumonia, came under our notice on the seventh day. The temperature was 106 5-10; pulse was 220; respirations 90. Whisky, which had been given previously to the extent of two ounces daily, was stopped. Carbonate of ammonia, caffeine salicylate, nitro-glycerine and 1-10 of a drop of aconite were given internally; camphorated lard applied externally; with the result that on the ninth day temperature stood 99; pulse 100; respiration 20. The child made a complete recovery.

“Case No. 2. L. was a child aged eight months, suffering from a very violent attack of entero-colitis. For three weeks previous to coming under our notice the patient received brandy, stimulating foods and alkaline mixtures. Fearfully emaciated, temperature 106, feeble pulse 182, frequent bloody discharges from the bowels, numbering as much as thirty in a day and constant vomiting, the child was considered beyond hope. Under these circumstances, and at this time we first saw her. Brandy and all foods were stopped; bowel flushings were given, 1-12 of a drop of tincture of aconite was administered every half hour and salicylate of caffeine every two hours. In twenty-four hours the temperature was 105 and the pulse 160. In two days, temperature was 102 and the pulse 140. In one week, temperature was 99 5-10, pulse 110. In three weeks, the patient was discharged cured.

“Case No. 3. Mrs. C., aged forty-three, who had been under treatment for seven weeks for metrorrhagia, nietortes and peritonitis came under our notice. Brandy which had been previously given in large quantities had proved of no avail and the patient was considered beyond recovery. We found her completely prostrated, temperature 102, pulse 170, and unconscious. The heart very weak and irregular. The brandy was discontinued, salicylate of caffeine and nitrate of strychnia were given with the result that in a short time the patient was convalescent and finally recovered.

“Each case in our hospital is an additional proof that whether found in wines, spirits or beers, alcohol can claim no right as an indispensable medicine.”

Dr. Lesser, who was Surgeon-General of the American Red Cross in the Cuban War said after his return from his first visit to Cuba that four out of six of his patients, to whom he allowed liquor to be given as a concession to the popular idea that it was necessary, died; while subsequently in treating absolutely without alcohol sixty-three similar cases, only one died, and he upon the day on which he was received at the hospital.

ALCOHOL IN OTHER HOSPITALSIn the spring of 1909 a circular letter was sent to some of the best known hospitals throughout the country asking if the use of alcoholic liquors had decreased in those institutions during the past ten years. From the replies received the following statements are taken:

Cook County Hospital, Chicago, sent figures for two years only, 1907, and 1908. With 28,932 patients treated in 1907, the bill for wines and liquors amounted to only $719.40. In 1908 with 31,202 patients the bill for liquors amounted to $970.65. This makes a per capita expenditure for liquors for 1907 of .024 cents, and for 1908 a per capita expenditure of .031 cents. The per capita expenditure for liquors during the same years in Bellevue and Allied Hospitals of New York city, with from 30,000 to 40,000 patients treated was .0246 and .029. Two or three cents as the yearly per capita expenditure for alcoholic liquors in the two largest hospitals in America is striking evidence that the physicians practicing there have not large faith in whisky, or other alcoholic liquors as remedial agents.

Long Island, N. Y., State Hospital: – “We are not using more than half the amount of alcohol we used ten years ago.”

Manhattan State Hospital, Ward’s Island, New York City: – “Our patient population has averaged nearly 4,500 the last four years, and we have had about 750 employees, many of whom are prescribed for by institution physicians. The per capita cost of distilled liquors for the last fiscal year was .0273 at this hospital.”

Milwaukee City Hospital: – “No alcoholic liquors are used to any extent in this hospital, or prescribed by the staff. I know of no move against such use of liquors, but venture the assertion that the physicians believe they have more reliable agents at their command for most cases.”

Pennsylvania Hospital, Philadelphia: – “We are now using about one-third the amount of liquor that was used in the Pennsylvania Hospital ten years ago.”

The Presbyterian Hospital of Philadelphia sent figures for the years from 1900 to 1908. Those for 1900 show the cost of liquors to be $774.20 and for 1908 only $331.48. The number of patients was not given.

Grady Hospital, Atlanta, Georgia: – “That less liquor is now used than formerly is a fact well known to all connected with the institution.”

Garfield Memorial, Washington, D. C., sent figures for ten years. For 1899 the cost of liquors was $490.08, with a steady decrease to 1908 when the cost was $274.58. Number of patients in 1899 was 1,171; in 1908, 1,898 patients. The per capita for 1908 was .144 cents.

University Hospital, Ann Arbor, Michigan: – “Very little alcohol is prescribed in this hospital.”

Maine General Hospital, Portland: – “Comparatively speaking, we use but little alcohol for the reason that we now have many remedies which, especially for continued use, are superior to alcohol, which twenty years ago we did not have. For the conditions or emergencies in which we think alcohol has a value it is used when required or deemed best.”

Buffalo, New York, State Hospital sent figures for six years which include cost of alcohol used in the manufacture of pharmaceutical preparations, which, of course, makes a very decided difference. Per capita for 1903 was 22 cents; for 1908 it was 18 cents.

Buffalo, New York, General Hospital: – “The use of alcohol as a drug in this hospital has diminished about one-third in the past ten years, but I wish to add in this connection that the use of all drugs has diminished in this hospital, and to the best of my knowledge in other institutions of a like character. The use of the microscope, and other studies have advanced the science of medicine the same as all other branches of learning, and other methods are coming to be used beside the use of drugs.”

Mount Sinai, New York City: – “The use of alcoholic beverages here for medical purposes is the exception rather than the rule. The majority of our cases are surgical cases, and in these alcoholic liquors are rarely prescribed for any purpose whatsoever.”

Massachusetts Homeopathic Hospital, Boston, sent figures for five years. For 1904 the cost of alcoholic liquors was $197.69 with 3,720 patients; for 1908, the cost was $69.82 with 4,543 patients. The per capita cost for the five years is as follows: 1904, cost .0531 cents; 1905, cost .0474; 1906, cost .034; 1907, cost .0171; 1908, cost .0153.

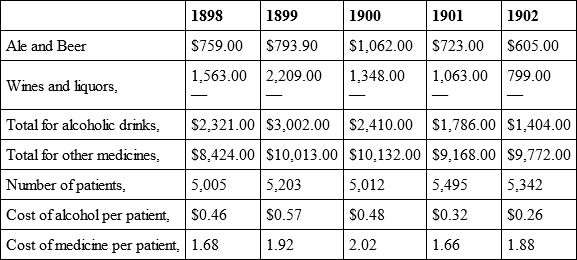

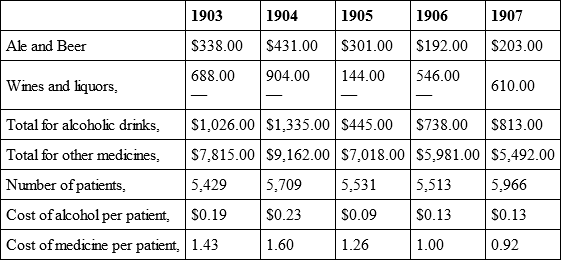

In the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal of April 15, 1909, Dr. Richard C. Cabot gave a table showing the decrease in the use of alcoholic liquors, and of other drugs in Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

The following is his table:

Dr. Cabot says: —

“Since there has been no fall in the price of stimulants or medicine, the diminished expenditure corresponds to a diminution in the number of doses of medicine and stimulants, and indicates a rapid and striking change of view among the members of the staff of the hospital, especially in the past five years, when it has become generally known that alcohol is not a stimulant but a narcotic and that drugs can cure only about half a dozen of the diseases against which we are contending.

“There has been during this period no increase in the proportion of surgical cases among the whole number treated, so that the decreased use of medicines and alcoholic beverages has not resulted from an increased resort to surgical remedies. On the other hand, there has been a great increase in the utilization of baths (hydrotherapeutics), of massage, of mechanical treatment and of psychical treatment, all of which accounts no doubt for part of the falling off in the use of alcohol and drugs.”

CHAPTER V.

THE EFFECTS OF ALCOHOL UPON THE HUMAN BODY

The body is made up mainly of cells, fibres and fluids. The cell is the most important structure in the living body. Life resides in the cell, and every animal may be considered a mass of cells, each of which is alive, and each of which has its own work to accomplish in the building up of the body.

The matter which forms the mass of a cell is called protoplasm, or bioplasm. It resembles somewhat the white of a raw egg, which is almost pure albumen. Cells make up the body, and do its work. Some are employed to construct the skeleton, others are used to form the organs which move the body; liver-cells secrete bile, and the cells in the kidneys separate poisonous matters from the blood in order that they may be expelled from the system.

These cells, composing the mass of the body, being very delicate, are easily acted upon by substances coming into contact with them. If substances other than natural foods or drinks are introduced into the body, the cells are injuriously affected. Alcohol is especially injurious to cells, “retarding the changes in their interior, hindering their appropriation of food, and elimination of waste matters, and therefore preventing their proper development and growth.”

“Bioplasm is living matter; it is structureless, semi-fluid, transparent and colorless. It is the only matter that can grow, move, divide itself and multiply, the only matter that can take up pabulum (food) and convert it into its own substance; and is the only matter that can be nourished. The bioplasm in the cell gets its nourishment by drawing in of the pabulum through the cell wall, and in that way building up the formed material while it is being disintegrated on the outer surface. This process is continually being carried on, and is what is meant by nutrition. Disintegration of the formed material is as essential as the building up of it. All organic structure is the result of change taking place in bioplasm. These small cell-like bioplasts are the workmen of the organism. All wounds are repaired by them, all fractures are united, and all diseased tissues brought back to their normal and healthy condition, unless there is not vitality enough to overcome disease, or they have been injured or killed by poisonous material. The body is kept in repair by this living matter, and all the functions of the body are but the result of its action. We may examine, watch and study bioplasm under the microscope; we see it take up pabulum and convert that which is adapted to itself into its own substance, while all other substances are rejected. We take a solution of what we call a stimulant and immerse the bioplasm in it, and we find that it increases its activity, moves faster, takes up more pabulum, and divides more rapidly than in the unstimulated condition. We next add an astringent, and it begins to move more slowly, and soon contracts into a spherical shape and remains contracted, or may move slowly to a limited extent, depending on the strength of the solution. We next take a relaxant, and gradually the living matter begins to spread in all directions, in a laxy-like manner, and becomes so thin as to be almost undiscernible, and takes up very little, if any, pabulum. If sufficiently relaxed or astringed, the movements may entirely cease so as to appear lifeless, but when a stimulant is again added the same result is obtained as before – it begins to move, and acts as vigorous as ever, which shows that it was not injured in the least by the agents used. Alcohol is called a stimulant. We take a weak solution of alcohol and try it in the same way; but we find that almost instantly the living matter contracts into a ball-like mass. Now, we may through ignorance suppose that alcohol acts as an astringent, and so we try to stimulate it with the same harmless agent before used, but no impression is made on it; it does not move; it is dead matter. These are demonstrable facts, and lie at the foundation of physiology, pathology and the practice of medicine. Alcohol destroys the very life force that alone keeps the body in repair. For a more simple experiment as to the action of alcohol, take the white of an egg (which consists of albumen, and is very similar to bioplasm), put it into alcohol, and notice it turn white, coagulate and harden. The same experiment can be made with blood with the same result – killing the blood bioplasts. Raw meat will turn white and harden in alcohol. Alcohol acts the same on food in the stomach as it does on the same substances before introduced into the stomach, and acts just the same on blood and all the living tissues in the system as out of it; and this alone is enough to condemn its use as a medicine.” From Alcohol, Is It a Medicine? by W. F. Pechuman, M. D., of Detroit, Michigan.

ALCOHOL AND STOMACH DIGESTIONThe nitrogenous portions of the food are the only ones digested in the stomach. The oily and fatty, as well as the starchy portions, are digested in the small intestines.

Very little was known about digestion until 1833, when Dr. Beaumont published the results of his investigations upon the stomach of Alexis St. Martin. St. Martin received a severe wound in the left side from a shot-gun. The wound in healing left an opening into the stomach about ⅘ of an inch in diameter, closed on the inside by a flap of mucous membrane. Through this opening the interior of the stomach could be thoroughly examined. Dr. Beaumont made hundreds of observations upon this young man, who was in his home several years. He says: —

“In a feverish condition, from whatever cause, obstructed perspiration, excitement by alcoholic liquors, overloading the stomach with food, fear, anger or whatever depresses or disturbs the nervous system, the lining of the stomach becomes somewhat red and dry, at other times pale and moist, and loses its smooth and healthy appearance, the secretions become vitiated, greatly diminished or entirely suppressed.”

One day after giving St. Martin a good wholesome dinner, digestion of which was going on in regular order, Dr. Beaumont gave him a glass of gin. The digestive process was at once arrested, and did not begin again until after the absorption of the spirit, after which it was slowly renewed, and tardily finished.

Gluzinski made some conclusive experiments with a syphon. He drew off the contents of the stomach at various times with and without liquor. He concluded that alcohol entirely suspends the transformation of food while it remains in the stomach.

Dr. Figg, of Edinburgh, fed two dogs with roast mutton; to one of them he gave 1½ounces of spirit. Three hours later he killed both dogs. The dog without liquor had digested the mutton; the other had not digested his at all. Similar experiments have been made repeatedly with like result.

The elements of our food which the stomach can digest depend upon the pepsin of the gastric juice for their transformation. Alcohol diminishes the secretions of the gastric juice, unless given in very minute quantities, and kills and precipitates its pepsin. It also coagulates both albumen and fibrine, converting them into a solid substance, thus rendering them unfit for the action of the solvent principles of the gastric juice. Hence, any considerable quantity of alcohol taken into the stomach must for the time retard the function of digestion.

Many experiments have been made with gastric juice in vials, one, having alcohol added, the other, not having alcohol. The meat in the vials without alcohol, in time dissolved till it bore the appearance of soup; in the vials to which alcohol was added the meat remained practically unchanged. In the latter a deposit of pepsin was found at the bottom, the alcohol having precipitated it. Dr. Henry Munroe, of England, one of the experimenters in this line of research, says: —

“Alcohol, even in a diluted form, has the peculiar power of interfering with the ordinary process of digestion.

“As long as alcohol remains in the stomach in any degree of concentration, the process of digestion is arrested, and is not continued until enough gastric juice is thrown out to overcome its effects.” —Tracy’s Physiology, page 90.

In The Human Body, Dr. Newell Martin says: —

“A vast number of persons suffer from alcoholic dyspepsia without knowing its cause; people who were never drunk in their lives and consider themselves very temperate. Abstinence from alcohol, the cause of the trouble, is the true remedy.”

Sir B. W. Richardson: —

“The common idea that alcohol acts as an aid to digestion is without foundation. Experiments on the artificial digestion of food, in which the natural process is closely imitated, show that the presence of alcohol in the solvents employed interferes with and weakens the efficacy of the solvents. It is also one of the most definite of facts that persons who indulge even in what is called the moderate use of alcohol suffer often from dyspepsia from this cause alone. In fact, it leads to the symptoms which, under the varied names of biliousness, nervousness, lassitude and indigestion, are so well and extensively known.

“From the paralysis of the minute blood-vessels which is induced by alcohol, there occurs, when alcohol is introduced into the stomach, injection of the vessels and redness of the mucous lining of the stomach. This is attended by the subjective feeling of a warmth or glow within the body, and according to some, with an increased secretion of the gastric fluids. It is urged by the advocates of alcohol that this action of alcohol on the stomach is a reason for its employment as an aid to digestion, especially when the digestive powers are feeble. At best this argument suggests only an artificial aid, which it cannot be sound practice to make permanent in place of the natural process of digestion. In truth, the artificial stimulation, if it be resorted to even moderately, is in time deleterious. It excites a morbid habitual craving, and in the end leads to weakened contractile power of the vessels of the stomach, to consequent deficiency of control of those vessels over the current of blood, to organic impairment of function, and to confirmed indigestion. Lastly, it is a matter of experience with me, that in nine cases out of ten, the sense of the necessity, on which so much is urged, is removed in the readiest manner, by the simple plan of total abstinence, without any other remedy or method.”

In Medicinal Drinking, by John Kirk, M. D., this passage occurs: —

“Especially in the matter of support, it is essential to our inquiry to examine fully into alcoholic influence on the change by which food introduced into the stomach becomes capable of passing into the circulation and constituent elements of the living frame. It may be best to suppose a case for illustration. Here, then, is a child of, say, six or seven years of age. This child is of the slenderer sex and has been brought into a state of extreme weakness as the consequence of fever. The fury of the disease is expended, but it has, as nearly as may be, extinguished life. The medical man’s one hope for saving this child is now concentrated in what he fancies to be ‘support.’ Beef-tea, arrowroot and port wine are prescribed. Let it be kept in mind that the pure wine of the grape is discarded in favor of alcoholic wine. Our question is, What effect will the alcohol in this wine have on that process by which the food is to prove really nourishing, and so to be that support which is the only hope for this child? Will it help her? or will it so hinder the necessary change in the food as to kill her, unless she has sufficient strength left to get above its influence? These are surely important questions. Neither of them can be set at rest by the fact that she recovers; for she may have strength enough, as many have had, to survive even a serious error in her treatment.

“What light, then, does true science throw on these important questions? All who know anything on the subject are aware that alcohol, instead of dissolving food, or aiding in its dissolution, is one of the most powerful agents in preventing that dissolution. On what principle, then, is it possible that its being mixed with the materials of food, in this case, can aid in their dissolution, so that they may more easily be changed into the fresh blood required to sustain and recover life in this child?”

He then refers to the experiments with gastric juice in vials, and proceeds: —

“Here, then, is indisputable evidence that alcohol effectually prevents that process which is known as digestion, and which is essential to food’s being of any use to support life in man. On what principle can the physician explain his introduction of it into the stomach of a child whose thread of life is attenuated to the slenderest hair?

“We urge the chemical truth that the alcohol, given to promote support, is of such a nature as to prevent that which would nourish, from effecting the end so much to be desired, and for which true food is adapted.”

The pure, unfermented juice of the grape, free from chemical preservatives, is now used by many physicians where the miserable concoction of drugs and alcohol, known as port wine, was once considered essential. Unfermented grape juice contains all the nutriment of the grape, without any of the poison, alcohol. After being opened it should be kept in a cool place, or it will ferment and produce alcohol. Fruit juices are very grateful to a fever patient, and should not be withheld as they are in so many cases. Dr. J. H. Kellogg, and other non-alcoholic physicians, recommend them highly. They are better than milk, as milk frequently produces “feverishness,” while fruit juices allay it.

For those who think beer or ale an incentive to appetite, Dr. N. S. Davis, and others, recommend an infusion of hops, made fresh each day. It is the bitter which promotes appetite, not the alcohol. For the sake of the little bitter in beer, it is not wise to vitiate the tone of the stomach with the alcohol it contains, and which is its active principle. Many mothers have become drunkards, secret drunkards, possibly, through the use of beer as a fancied aid to digestion. Multitudes of men suffer untold horrors from dyspepsia, caused by the beer which they mistakenly suppose to be a friend to their stomach.

EFFECTS OF ALCOHOL UPON THE BLOOD“The blood is a thick, opaque fluid, varying in color in different parts of the body from a bright scarlet to a dark purple, or even almost black.” If a drop of blood be placed under a microscope, immense numbers of small bodies will be seen. These are called blood-globules, or corpuscles, or discs. There are both red, and white or colorless, corpuscles. Each red corpuscle is soft and jelly-like. Its chief constituent, besides water, is a substance called hemoglobin, which has the power of combining with oxygen when in a place where that gas is plentiful, and of giving it off again in a region where oxygen is absent, or present only in small quantity. Hence, as the blood flows through the lungs, which are constantly supplied with fresh air, its corpuscles take up oxygen, which, as it flows on, is carried by them to distant parts of the body where oxygen is deficient, and there given up to the tissues. This oxygen-carrying is the function of the red corpuscles.