полная версия

полная версияAlcohol: A Dangerous and Unnecessary Medicine, How and Why

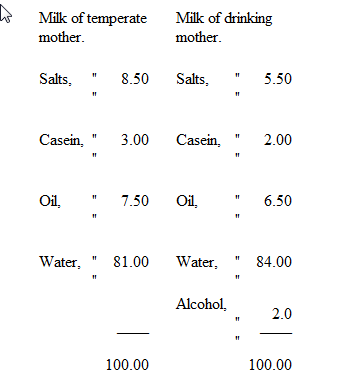

Dr. E. G. Figg, in The Physiological Operation of Alcohol, gives the analyses of the milk of a temperate woman in good health, and of a drinking woman as follows: —

Dr. Edward Smith says in his Practical Dietary: —

“Alcoholics are largely used by many women in the belief that they support the system, and maintain the supply of milk for the infant; but I am convinced that this is a serious error, and is not an infrequent cause of fits and emaciation in the child.”

Dr. James Edmunds, of the Lying-In Hospital, London, Eng., says in Diet for Nursing Mothers: —

“The nursing mother is peculiarly placed, in that she has to provide a supply of nutriment for the child which is dependent upon her, as well as for the ordinary requirements of her own system. The nutrition of the child is to be provided for upon the same principles, and by the same food-elements, as is the nutrition of the mother, the only difference being that the young child is possessed of less perfect masticatory and digestive powers, and therefore requires food to be presented to it in a state more simple, uniform, and readily assimilable than the adult, who is furnished with strong teeth, and possessed of a fully-grown stomach. The mastication, digestion, and primary assimilation of the nursing infant’s food is thrown upon the mother’s organs; but the tissues of the child are nourished precisely as are the tissues of the mother, and a nursing mother requires simply to digest a larger supply of wholesome, and appropriate food. As a matter of course mothers with imperfect teeth, or weak stomachs, cannot perform the digestion of extra food for the infant so well as those mothers who have an abundance of reserve power in their digestive apparatus; and with such patients, the question arises, how are they to make up for the deficiency which they soon experience in the supply of milk? Such mothers appeal to their medical advisers to prescribe some stimulant which will enable them to overcome the difficulty which they experience, and often are greatly dissatisfied if informed that there is no drug in the materia medica which will make up for structural weakness in the organs which masticate, digest or assimilate the food. The proper course for such women to adopt is a simple and rational one. They should assist their digestive apparatus as much as possible by securing an abundance of suitable and nutritious food, prepared in the best way, and as is most digestible, while they should lessen the demands of their own system by the avoidance of bodily fatigue, and mental excitement. These means, aided by that philosophical hygiene which is at all times essential to the preservation of pure and perfect health, will enable them to supply a maximum quantity of pure and wholesome milk; and further calls by the child require proper artificial food. Unfortunately such advice fails to satisfy many anxious mothers who refuse to admit, or believe, that they are less robust, or less capable, than other ladies of their acquaintance, and such mothers fall easy victims to circulars vaunting the nourishing properties of ‘Hoare’s Stout,’ ‘Tanqueray’s Gin,’ or Gilbey’s ‘strengthening Port,’ circulars which are always backed up by the example, and advice, of lady friends, who themselves have acquired the habit of using these liquors, and who view as a reproach to themselves the practice of any other lady who may not keep them in countenance, as the perfection of all moral and physical propriety. Unfortunately the pressure of such lady friends is often so persistent as to paralyse the influence of a conscientious and thoughtful medical adviser, while the appetites and beliefs of such friends often throw them into active antagonism to any medical adviser, who may not endorse the habits in which, as they believe, and no doubt conscientiously, duty to their child requires them to indulge. The only course that a medical practitioner, whose family is dependent upon his practice, can safely take with veteran mothers on this question, is to let them have their own way without reiterated admonition. When once they have acquired the habit of depending upon large quantities of beer for nursing their children, they become perfectly infatuated, and are practically incapable of passing through the probationary fortnight which takes place before the digestive apparatus can work under its natural, but to them strange, conditions, while the temporary longing for beer, and the sudden lessening of the quantity of milk afforded by their strained and impoverished systems, are at once set down as clear proofs that their medical adviser is a crochetty, and dangerous person, who must be superseded at the first convenient opportunity. Facts and arguments have no more influence on such mothers than they have upon opium-eaters, drunkards, or inveterate consumers of tobacco; while the extreme propriety of conduct which these ladies manifest, and the encouragement they receive from other medical men, make the convictions based upon their own personal sensations incontrovertible, and their position practically unassailable. I think I might fairly say that among the comfortable middle classes of society the views at present held on this question are so deplorable that a large proportion of children are never sober from the first moment of their existence until they have been weaned; while often after a few years the use of alcohol is again introduced to the children as a ‘medical comfort,’ as a part of their regular diet, or as an invariable accompaniment of all their juvenile visitation, and company-keeping. Under such circumstances, it is not surprising that temperance reformers appeal in vain on this question, and that their facts and arguments are viewed with plausible indifference, or insidious opposition, by persons whose appetites and instincts have been undergoing debasement, and perversion from the very dawn of their lives. My own deliberate conviction is that nothing but harm comes to nursing mothers, and to the infants who are dependent upon them, by the ordinary use of alcoholic beverages of any kind.

“Infants nursed by mothers who drink much beer also become fatter than usual, and to an untrained eye sometimes appear as ‘magnificent children.’ But the fatness of such children is not a recommendation to the more knowing observer; they are extremely prone to die of inflammation of the chest (bronchitis) after a few days’ illness from an ordinary cold. They die, very much more frequently than other children, of convulsions and diarrhœa, while cutting their teeth, and they are very liable to die of scrofulous inflammation of the membranes of the brain, commonly called ‘water on the brain,’ while their childhood often presents a painful contrast – in the way of crooked legs, and stunted or ill-shapen figure – to the ‘magnificent,’ and promising appearance of their infancy.

“Those ladies who adopt the general views I have thus expressed in relation to the nursing of their children, will want to know what is the ‘proper artificial food’ with which to supplement their milk when it is deficient in quantity. With some patients the milk will fall off in quantity at the end of two or three months. With others, although the quantity may not fall off, the child seems unsatisfied; and there is a third class with whom a profusion of milk is supplied, and the child thrives exceedingly, but the mother gets flabby, weak, nervous, pale and exhausted. In the last case, the mother is simply goaded on by susceptibility of her nervous system, or by inordinate activity of the breasts to yield an amount of milk which her digestive powers are not equal to providing for. The treatment of such cases should be simply repressive. The mother should separate herself somewhat more from the child, and make a rule of only nursing it from five to eight times in the twenty-four hours, while the neck of the mother should be kept cool in regard to dress, and cold sponging may be practiced carefully night and morning. Her attention should be diverted by outdoor exercise on foot, and additionally in a carriage if necessary. When the mother’s milk, though apparently not deficient in quantity, proves unsatisfying to the child, great attention should be paid to varying the diet of the mother, while such staple foods should be taken as are most easily and thoroughly assimilated into milk. The unsatisfying quality of the milk will generally be remedied by taking a more varied diet, together with three or four half pints of milk in the course of the day, accompanied with farinaceous matter, as in the shape of well-made milk gruel; and in case these measures fail, the only alternative is to supplement the mother’s milk by obtaining a wet-nurse to suckle the child three or four times a day alternately with the mother, or by feeding the child with proper artificial food. The same measures may be resorted to where the milk, though satisfying in character, is deficient in quantity; and in preparing artificial food for the child it must always be remembered that the food requires to be adapted to the stage of development which is manifested by a young infant’s digestive organs. The infant’s digestive apparatus is, in fact, designed to digest milk, and to digest nothing else, but when the teeth are cut farinaceous matter of a more or less solid character should be gradually mixed with the milk. Almost all the illnesses of infants under twelve months of age are caused by some gross impropriety of diet, or otherwise, on the part of the mother, for which the child suffers through the medium of the milk, or they are caused by feeding the child with improper artificial food. Thick sop, and many other articles often given as food are as indigestible to an infant of three months old as beefsteaks would be to a horse; and, until the child has cut its teeth, it should have nothing but food resembling the mother’s milk as closely as possible.

“The proper way to feed an infant of three months old, whose mother is only able to partially support it, is as follows: When the child wakes in the morning it should not go to the mother, but should be taken away by the nurse, and immediately fed from the bottle, sucking its milk through a suitable teat. After the mother has breakfasted the child may go to the breast, and during the day it should be alternately fed from the bottle, and nursed by the mother. At six o’clock the baby should invariably be placed in its crib, by the side of the mother’s bed, and fed just before going to sleep, and the habit of going to bed at six o’clock should be strictly and invariably enforced. If once the child be allowed to come down to the family circle after dark, the habit of going to sleep will be broken, and the child will continuously cry to come down. In the course of the evening the mother may nurse the child once, and at ten or eleven o’clock, when the mother goes to bed, the child should be again fed from the bottle, and the mother should have a basin of well-made milk-gruel; and by her bedside should be placed, at the last moment, as much gruel as she is likely to drink with relish during the night. Whenever the child is restless it should be taken out of its crib, gently, by the mother, and nursed, say two or three times during the night, and put back again into its crib, the child never being allowed to sleep with the mother. When the night is fairly over, and the child awakens, it should be fetched by the nurse, and have its first morning meal from the bottle. This plan of feeding should be persisted in continuously until the child has cut its teeth; and it is only when every means have been taken to ensure the sweetness, freshness and niceness, not only of the milk and water, but of the bottle and of the teat, and the child still fails to get on, that, in rare cases, I advise the admixture of a little farinaceous matter, in the way of food containing one part milk, and two parts of properly sweetened barley-water. As the milk teeth come through, other farinaceous matter may be gradually blended with the milk, and there is nothing better than to begin at about eight months with a teaspoonful of baked flour, well boiled in a pint of milk and water, or in the water, to be afterwards cooled with milk. Oftentimes a little salt, as well as sugar, will materially help its digestion. The child will do well on that food – the quantity being duly increased – until it has cut almost all its milk teeth, when it may eat bread and butter, rice, and egg puddings, and occasionally eat a boiled egg once a day. I believe that it is a great mistake to give red flesh meat to children in their early years, unless there be some very special reason for it, and then it should only be temporarily used; but nice potatoes, flavored with fresh gravy from a joint, may be given at dinner, as the child becomes able to feed itself. * * * * *

“Bear in mind that when you take wine, beer or brandy, you are distilling that wine, beer or brandy into your child’s body. Probably nothing could be worse than to have the very fabric of the child’s tissues laid down from alcoholized blood.”

Another English physician deplores “the pernicious habit of drinking large quantities of ale or stout by nursing mothers, under the idea that they thereby increase and improve the secretion of milk, whereas they are in reality deteriorating the quality of that upon which the infant must depend for health and life.”

Dr. Edis says: —

“Infant mortality is mainly due to two causes, the substitution of farinaceous food for milk, and the delusion that ale or beer is necessary as an article of diet for nursing mothers. * * * * * Countless disorders among infants are due simply and solely to the popular fallacy, that the nursing mother cannot properly fulfil her duties, unless she resorts to the aid of alcoholics.”

Dr. N. S. Davis says: —

“The opinion prevails quite extensively among certain classes of people, and with some physicians, that a liberal use of beer is beneficial to women while nursing their children. They drink it under the impression that it will both strengthen them and make their milk more abundant. But I have never seen a case in which it had been used regularly for any considerable period of time, where it did not result in more or less indigestion from gastric irritation and disordered secretions, and an early failure in the secretion of milk. It probably never increases the flow of milk any more than would the drinking of the same quantity of pure water; while the alcohol it contains, by daily repetition, induces congestion of the gastric mucous membrane, with disordered gastric and hepatic secretions.

“A case strikingly illustrating these results was examined by me to-day. The patient was a young married woman who was nursing her first child, now nine months old. At the time of her confinement she was in fair health, rather nervous temperament, weight 120 pounds. During the first few days her milk did not flow very freely, and she says her physician advised her to drink beer. Consequently she commenced to drink a glass of beer at each mealtime, and a bottle during the night. During the first six months she had sufficient milk for her baby; but before the end of that time she had begun to suffer from flatulency, constipation, gaseous and acid eructations, what she calls ‘heart-burn,’ and sometimes vomiting. During the last three months she has suffered, in addition to the preceding symptoms, one or two attacks each week of extreme pain, from the lower point of the sternum to the back between the scapula, accompanied by retching, or severe efforts to vomit. To relieve these attacks she has taken liberal doses of gin, in addition to her regular supply of beer. Now at the end of nine months, her milk has nearly ceased to flow, her bowels are costive, her stomach tolerates only small quantities of the simplest nourishment, her flesh and strength are very much reduced, her weight being only 96 pounds; and yet she thinks both the beer and gin make her feel better every time she takes them. Such is the delusive power of the anæsthetic effect of alcohol. A persistence in the same management would probably terminate fatally in from six to twelve months more, from chronic gastritis, and inanition. But if she will rigidly abstain from all alcoholic remedies, and take only the most bland, unirritating nourishment, aided by mildly soothing and antiseptic remedies, and fresh air, she will slowly recover.”

In a clinical lecture delivered before the Senior Class in the Northwestern University Medical School, Dr. Davis told of a case similar to the preceding: —

“The flow of milk in her breasts has also diminished to such a degree that she does not have half enough for her baby. Yet she says the beer makes her feel better after each drink, and that the gin helps to relieve the severe attacks of pain, and consequently she thinks she could not do without them. It is undoubtedly true that the patient feels temporary relief from the anæsthetic effect of the alcohol in her beer and gin, just as she would from any anæsthetic or narcotic. And it is equally true that so long as the alcohol is present in her blood it so modifies the hemoglobin and albuminous constituents, as to diminish the reception and internal distribution of oxygen, and thereby retards metabolic changes. But the combined influence of the alcohol in retarding the internal distribution of oxygen and the drain upon the nutritive elements of her blood, in furnishing milk for her baby, led to rapid impoverishment of the blood and tissues, and the early establishment of a sufficient grade of gastritis to cause indigestion, frequent vomiting, and, later, paroxysms of severe gastralgia, with general emaciation, and loss of strength.

“In accordance with the present popular ideas, both in and out of the profession, this patient tells me she has tried a great variety of foods, peptonized, sterilized, and predigested, but all to no purpose. And why? – Simply because her troubles are not in the kind of food she takes, but in the morbid condition of her blood, and of the mucous membrane and nerves of her stomach. Consequently the rational indications for treatment are: (a) to get her stomach and blood free from the alcohol of beer and gin; (b) to encourage the reception and internal distribution of oxygen by plenty of fresh air; (c) to give her the most bland, or unirritating food in small, and frequently repeated doses, of which good milk with lime-water, and milk and wheat-flour gruel are the best; (d) such medicines as possess sufficient antiseptic, and anodyne properties to allay the irritability of the gastric mucous membrane, and lessen fermentation.”

CHAPTER X.

COMPARATIVE DEATH-RATES WITH AND WITHOUT THE USE OF ALCOHOL AS A REMEDY

A study of statistics relating to the difference in results of the treatment of disease with and without the use of alcohol, cannot but be of great interest to all students of the alcohol question. The appended statistics are culled mainly from the Medical Pioneer of England, now, Medical Temperance Review, the journal of the British Medical Temperance Association, and from the Bulletin of the American Medical Temperance Association.

A paragraph in the British Medical Journal, for Dec. 2, 1893, says: —

“An interesting fact has been noted by Dr. Claye Shaw, at the London County Asylum, Banstead, for the Insane. Since the withdrawal of beer from the dietary, the rate of recovery has gone up. During the past year, for example, the recoveries reached 46.97 per cent. Nearly one half of the patients had thus recovered during the period stated. The inmates take their food better without the liquor, and they are thus taught that intoxicants are not a necessity of ordinary health.”

In the Medical Pioneer for January, 1894, Dr. John Mois, medical superintendent of West Haven Infectious Diseases Hospital, states that prior to 1885 he had treated 2,148 cases of smallpox “in the usual routine method, with the use of alcohol when the heart’s action seemed to indicate it;” resulting in a mortality of 17 per cent. But since 1885 he has treated 700 additional cases under similar circumstances except that the use of alcoholic preparations was entirely omitted, and the resulting mortality was only 11 per cent.

In the same journal, Dr. J. J. Ridge states that he had treated the 200 cases of scarlet fever admitted into the Enfield Isolation Hospital during the years 1892 and 1893, without alcohol in any form, with a mortality of only 2.5 per cent.; while the mortality in the hospitals under the Metropolitan Asylums Board in 1893, in which alcohol was used in accordance with the usual practice in scarlet fever, was 6.3 per cent.

Dr. J. J. Ridge says later: —

“In January, 1894, I published the result of the treatment of the first 200 cases of scarlatina admitted into the temporary wards of the Enfield Isolation Hospital during 1892 and 1893. I stated that there had been five fatal cases, but that one was dying when admitted and only lived a few hours. The mortality was 2 per cent., or 2.5 if the later case is included.

“Since then 300 more cases have been admitted and discharged and among these there have been 7 fatal. Hence there have been 14 deaths in 500 consecutive cases extending over a period of a little more than four years. One of these ought to be excluded, no time having been given for treatment. Hence the mortality has been just 2.6 per cent. This, I think it will be admitted, is a low mortality, although it is possible it may be even lower when the cases are treated in a permanent hospital about to be erected.

“It may be interesting to state that 4 of the cases died on the third day after admission; 1 on the fourth; 1 on the sixth; 1 on the tenth, with pneumonia; 1 on the thirteenth; 1 on the fifteenth; 1 on the sixteenth; 1 on the eighteenth; 1 on the thirty-sixth, with nephritis and pleuropneumonia; and 1 on the forty-sixth, with otitis and meningitis.

“All the cases have been treated without alcohol either as food or drug, although many have been of great severity with various complications. It is certain that the absence of alcohol has not been detrimental, since the mortality is less than three-fourths of that of the mortality among all notified cases in England and Wales. I am bound to say that it is my firm conviction that had alcohol been given in the usual fashion, the death-rate would have been higher. Cases have been admitted to which alcohol has been given previous to admission, apparently with harm, as they have improved without it. One case was particularly noticeable in this respect. A child, aged 6, had had a good deal of whisky, and was supposed to be dying when admitted on the fourth day of the disease, so that the doctor who had seen it was surprised, when he called the following day to inquire, to find it was still alive. Without a drop of alcohol it began to improve and made a good recovery. I may say that delirium is very rare, even in the worst cases treated non-alcoholically.”

Dr. Norman Kerr says: —

“In my paper on ‘The Medical Administration of Alcohol,’ read to the section of medicine at the Sheffield meeting in 1876, I cited several medical testimonies in favor of non-alcoholic treatment of fevers, notably that of my friend, the late Dr. Simon Nicolls, who had a mortality of less than 5 per cent. in 230 cases.

“The record of the results of a greatly lessened administration of alcohol in the treatment of smallpox in the London hospital ships, is of deep interest. Having been requested to inquire into the effects of this diminished alcoholic stimulation on mortality and convalescence, Dr. Birdwood stated that though the gravity of the cases had increased, with a mortality of 15 per 100 in the metropolis, the ship’s death-rate had remained at less than 7 per 100. Convalescence had been more rapid, and there had been fewer and less serious complications from abscesses and inflammatory boils. Other causes had contributed to this improvement, but the medical officers attributed a considerable share in the amelioration to a greatly diminished prescription of alcohol.”

The Medical Pioneer says: —

“In 1872 there appeared in the Saturday Review an article in which the medical practitioners of this country were accused of inciting their patients to free drinking, and in the discussion which this article called forth, Dr. Gairdner, of Glasgow, said that fever patients in that city, when treated with milk and without alcohol, did much better than those reported as having been treated by Dr. Todd with large doses of alcohol; the latter resulting in a mortality of about 25 per cent., while those treated by Dr. Gairdner with milk had had a death-rate of only 12 per cent. About this time the British Medical Temperance Association was founded, owing to the exertions of Dr. Ridge, of Enfield, and in 1876 it was enrolled, under the presidency of Sir B. W. Richardson. It now contains 269 members in England and Wales, 53 in Scotland and 80 in Ireland, or more than 400 altogether, all professional men and women. This, I think, is but a sign of the change of opinion on the use of alcoholic fluids in medical practice, for all who remember what medical practice was in London thirty years ago know that the use of wine and brandy in hospital practice was so common that it was quite a rarity in some hospitals to find a patient who was not ordered, by some of the staff, from three to four ounces of brandy or six to eight fluid ounces of wine. The expense caused to the hospitals by this practice was, of course, great, and increased notably between 1852 and 1872, owing to the prevalence of the views of Liebig and his follower, Dr. Todd. The writings of Parkes, Gairdner, Dr. Norman Kerr and of Sir B. Ward Richardson, Dr. Morton and others, gradually lessened this predilection for treating diseases by alcohol, and accordingly between 1872 and 1882 a great change came over the practice of London hospitals. Thus the sum paid for milk in 1852 in Saint Bartholomew’s Hospital was £684, and in 1882 it was £2,012; whilst alcohol in that hospital cost in 1852, £406; in 1862, £1,446; in 1872, £1,446; and in 1882 only £653. Westminster Hospital in 1882 spent £137 on alcohol and £500 on milk. One hospital, St. George’s, long continued to use large quantities of alcohol. That hospital in 1872 had the high mortality among its typhoid fever patients of 24 per cent., which was twice as high as that noted by Dr. Gairdner as occurring in Glasgow, when alcohol was abandoned and milk used instead. Dr. Meyer, who reported these cases of typhoid treated in Saint George’s Hospital at that time, mentioned that alcohol in large doses was given to 87 per cent. of the patients. Three-fifths of these patients took daily eight ounces of brandy when there was danger of sinking from failure of the heart’s action. One-fourth of the number took sixteen fluid ounces of brandy in the 24 hours.”