Полная версия

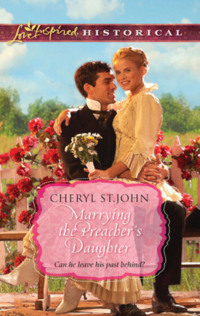

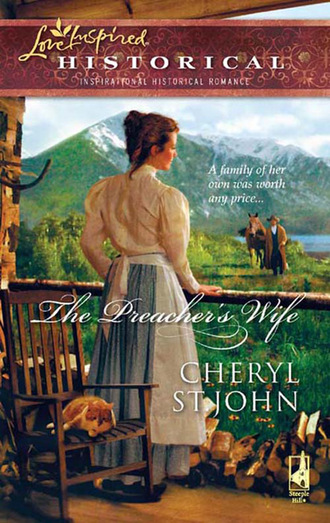

The Preacher's Wife

After searching and finding what they wanted, they returned to the reverend’s with the cookbook. Elisabeth immediately took Anna aside and spoke to her in soft tones Josie couldn’t hear.

Elisabeth hadn’t warmed to Josie, and it seemed she wasn’t comfortable with the fact that Anna had taken to her. Elisabeth got out a slate and chalk and helped Anna with numbers.

Some time later, Josie and Abigail were planning the evening meal when Samuel rode past the house on horseback. He had obviously bathed and shaved, and his neatly trimmed chestnut hair shone in the sunlight. He wore a new pair of denim trousers, a pale blue shirt and a string tie.

He led the animal into the enclosure and headed toward the house. Josie turned her attention to their list until the pleasing scents of sun-dried clothing and bay rum reached her. Abigail shot across the room to hug him. The holster and revolver still hung at his hip.

He met her gaze, so she asked, “Have you eaten?”

“Haven’t had time to think about food, truthfully.”

“I’ll make you something you can take along.”

“That’s kind of you. Who’s coming with me?”

“Elisabeth,” Abigail answered. “I’m going to help Mrs. Randolph make bread pudding. We have a recipe for lemon sauce.”

“That’s fine.” Samuel nodded. “And you’ll work on your studies. Run and fetch Elisabeth for me, please. Where’s Anna?”

“She found Reverend Martin’s cat,” Abigail answered on her way toward the hall. “Right now she’s watching it sun itself.”

One corner of his mouth inched up, and Josie found herself intrigued by the possibility of a smile on his clean-shaven face.

He looked back and found her gaze on him. “Would you prefer I take Anna along, since Elisabeth won’t be here to look after her?”

“Anna’s no trouble,” she replied. “If she wants to stay, I’ll keep an eye on her.”

“Thank you, Mrs. Randolph.”

“Would you mind calling me Josie? When I hear you say Mrs. Randolph I look for my mother-in-law—a fine woman of God,” she clarified quickly.

He raised his chin in half a nod.

She sliced bread and made a sandwich that she wrapped and handed to him. “There’s a basket of apples just inside the pantry if you’d like to take a couple. You and Elisabeth might get hungry before you return.”

He accepted the sandwich and met her gaze. His eyes were the color of glistening sap on a maple tree. The degree of sadness and disillusionment she read in their depths never failed to touch her. She wished she could do something that would remove that look.

“Your kindness is what my daughters need right now, Josie.” They were alone in the kitchen, yet he spoke softly as though he didn’t want to be overheard. “They’ve been through a lot.” He paused and his throat worked.

His loss was so recent, his pain so fresh. He’d obviously loved his wife very much. Josie didn’t presume to know how the man felt, and she knew words wouldn’t help right now. She understood and respected his grief.

She found her voice. “They’re lovely children, Reverend.”

“Every time I look at them, I see how fragile they are. How young and…” Samuel glanced away. “And vulnerable. They’re hurting.” He drew his gaze back to hers. “Elisabeth is handling it her own way, and I know she’s difficult. But…well, thank you for understanding.”

“I don’t believe in coincidence.”

Samuel’s eyes showed a spark of interest. “What do you mean?”

Chapter Four

“You’re here for a reason,” Josie answered. “I’m open to whatever God has planned.”

He didn’t say anything, but he swallowed hard and nodded.

Elisabeth entered the room, followed by Abigail. Elisabeth paused and glanced from her father to Josie. “I’m going with you.” She raised her hem, revealing a pair of trousers under her skirt.

“I figured as much, so I saddled the other horse. Let’s grab a couple of apples and head out.”

Josie and Abigail followed them onto the back steps and watched as father and daughter mounted their horses.

Abigail waved until they were out of sight. Josie was beginning to wonder if the girl was sorry she hadn’t gone along, until Abigail turned wide, eager eyes to her. “Can we start now?”

Josie agreed with a smile and they went back in. Buttering a baking dish, she asked, “Do you like to ride?”

She shook her head. “Not so much. Do you?” Abigail studied all the ingredients on the table. “What should I do?”

“Tear this bread into little pieces and drop them in the pan,” Josie said before answering her other question. “I think I’d like to. I haven’t been on a horse since I was small, and my uncle took me.”

Abigail picked up the bread. “We only took carriages in Philadelphia. I never rode, till Papa told us we were moving to Colorado. He said we needed to learn, and he taught us.”

Josie cracked eggs into a bowl and whipped them with a fork. “I’ve never been to a city as big as Philadelphia. I’ve lived here most of my life. What were your favorite things to do back home?”

“I liked school.” Abigail layered the bottom of the pan with bits of torn bread. “And parades. And when school was out we took tea in the afternoon, so we still got to see our friends when their mothers brought them or we went to their houses. May I put in the cinnamon?”

“Two teaspoonfuls. That sounds like fun.” Josie enjoyed how she and Abigail often held two conversations at once.

“Oh, it was. My Mama has a china tea set with violets painted on the pot and the cups.” She paused on the last chunk of bread. “I wonder where it is.”

“Your father put your things in storage. I’m sure he was careful to store the tea set where it would be safe.”

Abigail dropped in the last piece of bread, measured the cinnamon and then brushed her hands together with a flourish. “Now what?”

“Now we whip the egg mixture, pour it over the top and bake it.”

“Was this in the recipe book, too?”

“Actually, no. I just remember how, from seeing my mother do it.”

“Maybe we better write it down so I can remember when we get to Colorado. I might wanna make it for my papa.”

Josie studied Abigail’s serious blue eyes. The afternoon sun streaming through the window caught her pale hair and made it glisten. The girl’s foresight touched her. She’d lost her mother, and she needed to cling to familiar things. She needed to feel safe. “That’s a very good idea. In fact, I’ll make you a little book of all the recipes we use together.”

Her expressive face brightened. “You will?”

Josie nodded. Just then, Anna called them to come observe the cat batting at a fly on the windowsill. The child was fascinated by the feline’s swift movements, and then grimaced when it caught the insect and ate it. Josie hid her amusement. “I have an idea.”

“What is it?” Anna asked.

“I have a tea set. Why don’t you and Abigail come home with me for an hour or so, and we’ll have tea.”

Anna scrambled to her feet. “Do you got any lemon cakes or raisin scones?”

“I don’t, but I have some sugar cookies. Those will do, won’t they?”

Anna’s delighted smile was all the answer required.

The afternoon passed more quickly than any Josie could remember. After they’d had tea and cleaned up, then taken the sheets from the line and folded them, the girls got comfortable on their bed and read while Josie made up the reverend’s bed with fresh sheets and put away the towels.

She waited supper until Samuel and Elisabeth arrived. Josie ate in the kitchen with the girls, while Samuel kept Henry company, so they could talk about the calls he’d made. The bread pudding was well received, and Reverend Martin even asked for seconds. She refused offers of help to wash the dishes, and the girls went up to their room to study.

Later, she made coffee and carried a tray to the men and served them.

“Sit with us,” Reverend Martin invited. “Unless you have to be going.”

She hesitated only momentarily. Evenings were dreadfully long at her house. She jumped at the chance to avoid another one. “I’ll get a cup.”

Samuel stood until she had poured her coffee and taken a seat. “Your daughters are delightful company,” she told him. “I think even Daisy is warming to Anna.”

Henry explained how Anna and the feline had held a staring match most of the afternoon. He raised one eyebrow. “Sam said the Widow Harper seemed a trifle standoffish.”

Josie knew the woman. Mrs. Harper had been a widow for as long as Josie could remember, though others in town recalled a husband.

“And it seems she’s added a chicken to her pets since I was there last,” he told her.

“There was a sheep in a pen right beside the front door,” Sam said.

“I knew about the lamb,” Josie said. “I guess it grew up and was too big for the parlor.”

“She’s not too keen on people,” Henry understated. “Prefers her critters.”

“She didn’t care much for our visit,” Samuel told them. “Feeling was mutual, actually. Elisabeth sat on a footstool with her gaze riveted on that chicken, like it was going to fly up and peck her eyes out at any minute.”

Josie fought back a laugh by pursing her lips. Finally, she managed to say, “I would probably have done the same.”

Reverend Martin laughed then, a chuckle that started slow and built, until he held his sore ribs and grimaced.

Samuel’s cheek creased becomingly in a grin that gradually spread across his face.

Why his crooked smile was of special interest, she couldn’t have said, but the sight warmed and lifted Josie’s heart.

His laugh, once it erupted, was a deep, resonating sound that Josie felt through the floorboards. She knew instinctively that laughing was something he hadn’t done for a long time. She joined their merriment with a burst of laughter.

A shriek came from upstairs, effectively silencing their good humor. The sound came again, followed by a thump on the floor above.

Samuel shot from his chair and Josie followed close behind. He took the stairs two at a time while she gathered her hem and kept a slower pace.

The lamp on the hallway wall led them to the girls’ bedroom, and Samuel darted in. Josie found the oil lamp on the bureau and lit it.

She couldn’t identify the sobbing, but Abigail’s father went unerringly to the larger bed, where the covers were strewn onto the floor and Abigail sat with her arms over her head, white-clad elbows pointed toward the ceiling.

Elisabeth sat up from the narrow bed where she slept alone and blinked sleepily at them.

Anna was on her knees on the mattress beside Abigail, reaching out to stroke her sister’s mussed hair.

“It was Mama,” Abigail choked out, tears glistening on her cheeks. “Mama was in the water.”

Behind her, Anna burst into tears.

Samuel lifted Abigail and she wrapped her arms and legs around his waist and clung to him. He splayed one hand across her back and smoothed her hair with the other, making comforting shushing sounds.

Anna’s sobs broke Josie’s heart, and the sight of Sam holding Abigail so tenderly stirred feelings from her childhood, reminded her she’d never been held and comforted by her father. She couldn’t just stand by and do nothing, so she went to the side of the bed and knelt to touch Anna’s arm.

Anna immediately lunged toward her, her weight taking Josie by surprise and nearly toppling her. She regained her balance and sat on the edge of the bed, where Anna nestled right into her lap and tucked her head under her chin. The sweet scent of her hair and her trembling limbs incited all of Josie’s nurturing instincts. The girls’ heartbreaking sobs brought a lump to her throat and moisture to her eyes. She held Anna securely, rubbing her back and rocking without conscious thought. After a few minutes, Anna’s sobs dwindled.

Josie recalled her poignant words about her mother. Her gaze touched on a rag doll lying on the floor, then moved to the narrow bed where Elisabeth had lain back down and was staring at her. Josie stroked Anna’s back and gave Elisabeth an encouraging smile. The girl pulled the sheet up around her shoulders and rolled to face the other way.

“It was just a dream, Ab,” Samuel said to his daughter. “Just a dream.”

“But it was real.” Her voice trembled as she explained. “It was just like the day Mama died. I could hear the water….”

At those words, Anna trembled again in Josie’s arms. Oh, Lord, please comfort these children.

“And I could see her.”

“I know,” Samuel said. “I know.” He lowered her to the bed and perched beside her on the edge opposite where Josie sat holding Anna. In the lantern light, his face was etched with shared suffering. He gathered the bedding and covered Abigail with the sheet. “Dreams do seem very real.”

Abigail snuggled into the bedding.

“Remember the psalm we found?” Samuel asked her.

She nodded. “Will you say it, Papa?”

“‘When thou liest down, thou shalt not be afraid; yea thou shalt lie down, and thy sleep shall be sweet.’” His voice and those inspired words sent a shiver up Josie’s spine.

Sam closed his eyes. “Merciful Lord, give Abigail and Anna and Elisabeth sweet sleep this night.”

“Yes, Lord,” Abigail said and closed her eyes.

“Yes, Lord,” Josie said under her breath.

The remaining tension drained from Anna’s frame and she relaxed.

Josie’s chest ached with compassion for this man and his daughters. She admired his love for them, his dedication to their well-being, and was moved by his trust in God to comfort them. They had no idea how blessed they were to have a father who was present in their lives.

Samuel opened his eyes and nodded at Josie. She urged Anna from her lap, and the child slid under the covers to snuggle beside her sister.

“Good night, Mrs. Randolph,” Anna whispered. “Thanks for the hugs.”

She wanted to cry herself, but instead she gave the child a reassuring smile. “Good night, Anna.”

Josie turned out the lamp and followed Samuel into the hallway, where he pulled the door closed and stood in the golden light of the wall lantern. When he met her eyes, she read his anguish.

“I never know what to say,” he told her.

“You said exactly the right things,” she assured him. “And you’re there for them, that’s what’s important. When they need you, you’re there.”

“It doesn’t seem like enough.”

“We’re never enough in our own ability,” she assured him. “When we acknowledge that is when God works through us. And He worked through you in there.”

He turned his face aside, and his voice was thick when he said, “Thank you.”

She gathered her hem and moved toward the stairs.

Sam watched her leave, his thoughts a little less confusing than they’d been for some time. He recalled what she’d said about not believing in coincidence. It was no accident that his family was staying in this house. He’d been desperate, thinking he was unable to help his daughters. He’d prayed for guidance, for wisdom, for the weight of the burden to be lifted.

And now, for the first time in months, Sam didn’t feel quite so alone.

Josie took the hot iron from the stove and pressed the wrinkles from a pair of plain white pillowcases. The previous evening had been on her mind all morning. A girl as young and sweet as Abigail shouldn’t have nightmares. Her terror had stricken fear into Anna, as well. But their anguish was understandable, considering all they’d gone through.

While it was difficult to observe the younger girls’ misery, Elisabeth’s detachment from the episode was what bothered Josie the most. Elisabeth had watched her sisters until meeting Josie’s gaze, and then she’d turned away—as though unwilling to admit any part in it or to show her feelings. Josie folded the pillowcases and glanced over at Abigail, who was sitting at the table reading a book. Anna was probably cat-watching, and unless her father was present, Elisabeth spent most of her time upstairs.

“What are you reading?” Josie asked.

The girl marked her place with an index finger and looked up. “It’s a story about a boy growing up on a farm. Farms sound like great fun. Have you ever lived on one?”

“No, but I’ve visited quite a few. We’re in the middle of farm country.”

“Maybe we could go see.”

“A lot of the members of our congregation are farmers. If you went along with your father when he makes his calls, you’d get to see where they live.”

“Really?” Abigail looked excited for a moment, but then her expression changed. “Elisabeth joins Papa when he goes calling. Unless there’s school, of course. Do you suppose she saw a farm yesterday?”

Was Abigail feeling unwelcome? “She may have.”

Abigail slid a delicate, tatted marker in the shape of a cross between the pages and closed her book. “I’m gonna go ask her.” She scampered up the stairs.

A knock sounded on the back door, and Josie set the iron on the stove to see who was calling. Grace Hulbert stood holding what appeared to be a pie covered with a dish towel.

“Come in,” Josie greeted her. “The reverend’s in the parlor.”

“I brought an apple pie for the traveling preacher and his family,” Grace told her, peeling back the fabric to reveal a golden-brown crust with a perfectly crimped edge. “Is he here? The preacher man?”

“No, he’s out.”

“Is it true he’s a widower?”

“Sadly so. His wife drowned.” Josie took the pie and set it inside the tin-fronted safe.

“They say he wears a holster and a gun about town. Is it so?”

Josie wondered where that question had come from. “I’m certain everyone on their wagon train needed a gun to protect themselves—and to hunt. Is that so unusual?”

“It’s unusual for a man of the cloth. Has he shot anyone?”

“I have no idea, Grace. What kind of question is that?”

Grace pinched off her white gloves one finger at a time. “He’s the latest bachelor in town, so of course there’s speculation.”

“Bachelor?” Josie’s temperature rose a degree. Grace was a married woman, but she had a daughter who’d been on the shelf since her fiancé ran off six months ago. Josie leveled her gaze on the woman. “Would you like to visit with Reverend Martin? He’s in the parlor.”

“Oh, no.” She had one glove off and stopped removing the other. “I have to run. I just wanted to leave the pie.”

“I’ll let Reverend Martin know you were here.”

Grace headed for the door, but Anna appeared just then. “May I help with the ironing?”

“Is this one of the traveling preacher’s daughters?” Grace asked, turning back.

“This is Anna. Anna, Mrs. Hulbert.”

“How do you do, Mrs. Hulbert,” she said shyly.

“I do quite well, thank you, Anna. It’s a pleasure to meet you. You’re sure a pretty little thing. Do you take after your father?”

Anna moved to stand beside Josie and seemed disinclined to respond.

“You can sprinkle the sheets to dampen them while I see Mrs. Hulbert out,” Josie told her. “Then we’ll figure out what to fix for lunch.”

Grace didn’t give her a chance to move to the door. “I’ll be going.”

She let herself out and the door clicked shut. Josie stared at it for a moment, absorbing that odd exchange. The women of Durham were looking upon Samuel Hart as a bachelor? She tried to shake off the disgust that knowledge made her feel.

Anna was gazing up at her with a curious wrinkle in her brow. “Do I take after my Papa?”

Josie took a sheet from the basket. “Of the three of you, your eyes are most like his. Yours lend themselves to green sometimes, though. Like today, in that pretty green calico dress.”

Anna looked down and wrinkled her freckled nose. “This old thing was Abby’s.”

“You’re fortunate to have sisters who wore such nice clothing and took good care of it.”

The child cocked her head. “Papa says some little girls don’t have nice dresses at all, and they would love to have hand-me-downs.”

“Your papa’s right.”

“He says it’s foolish to buy new dresses, when we already have perfectly good ones that fit me soon enough.”

Josie understood the practicality of reusing their clothing, but she also knew the pleasure of having a new dress. “Surely you’ve had a new dress.”

“I get one for my birthday every year. And one when school starts. But people saw Abigail wear all these other ones.”

“You won’t have that problem now, will you?” she asked. “You’re meeting all new people, and they won’t know someone wore that dress before you.”

Anna smiled her charming missing-tooth smile and all was well for the rest of the afternoon.

That evening, Josie prepared their meals and served the reverend and his houseguest in the study. Samuel thanked her, and she met his eyes. Grace Hulbert’s brash curiosity came to mind immediately. If Grace could see the pain that Josie read in his eyes, she wouldn’t be thinking of him as though he were a prize horse up for sale to the highest bidder.

Josie ate in the kitchen with the girls. They were just finishing when Sam carried in his and the reverend’s dishes. “You’re an excellent cook, Mrs. Randolph.”

She looked over at him with a raised brow.

“I mean Josie. Thank you.”

“You’re welcome. Mrs. Hulbert brought pie for your family.”

He set down the plates. “That was kind. Why don’t we have it later this evening? Girls, I’d like you to help Mrs. Randolph with the dishes.”

“Shouldn’t we work on our studies?” Elisabeth asked.

“Tomorrow’s Sunday. Make sure your clothing is ready, and then, after our family time, you may enjoy the evening any way you like.”

Elisabeth looked at Josie. “Our Sunday dresses need to be pressed.”

“I’ll get out the irons for you,” Josie answered.

“I don’t know how to iron,” Elisabeth replied.

“It’s not difficult. I’ll show you how.”

“I know how to sprinkle,” Abigail added cheerfully.

Elisabeth cast her father a beseeching look.

“Thank you,” he said to Josie. “Elisabeth is a quick learner. And she will help with her sisters’ dresses, as well.”

Elisabeth’s shoulders drooped. “Yes, sir.”

“Papa?” Abigail asked. “When you go calling at a farm, can I come with you? Mrs. Randolph said the parishioners are mostly farmers, an’ I want to see their animals.”

“Of course you may come, Abby.”

“Will Elisabeth come that day, too?”

He blinked, but didn’t pause in replying, “We’ll talk about it. After your dresses are pressed, I’d like the three of you to get your wraps and come for a walk with me.”

“At night?” Anna asked.

“Night is when you can see God’s heavens most clearly,” he replied.

“Yes, sir,” they replied one at a time.

Josie kept the stove hot and set two irons on top. Abigail sprinkled their dresses and, using Elisabeth’s dress, Josie showed them how to press the collars and sleeves first, then the bodice and lastly the skirts. Elisabeth did an adequate job on her sisters’ clothing, and they carried their dresses upstairs and hung them.

The girls came down with capes and bonnets, and the Hart family swept out of doors, leaving the house silent.

Sam held Anna’s delicate hand in his, feeling the weighty responsibility of protecting these daughters he loved so well. He’d never felt so inadequate or so incomplete, and he didn’t like it. He’d been very careful laying plans for safety and finances, and so far he’d seen most of his puny plans thrown back in his face.

So far, Josie had been the best thing that had happened to them since they’d left home. He didn’t want to take advantage of her kindness or overload her with their additional care. Her kindness and selfless generosity was like a healing balm to his conscience, and he hoped her attention would be healing for his daughters, as well.

“While we are guests in the parsonage, I want the three of you to help as much as you can. Mrs. Randolph already cares for Reverend Martin’s needs, and we are an added burden. Your mother and I didn’t prepare you for this life. I know that. She took care of you, and things were easy in Philadelphia. I told you it would be an adventure coming west, but I didn’t tell you about all the difficulties. On top of everything else, your mother’s absence is an exceptional hardship.”