Полная версия

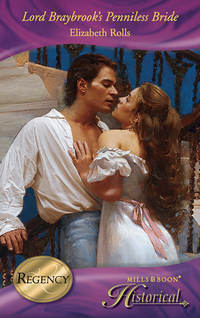

Lord Braybrook's Penniless Bride

Miss Trentham, who, according to the perfunctory description in Harry’s last letter, had blue eyes and black hair—Christy muttered a distinctly unladylike word—just like Lord Braybrook’s. Indeed, if they were anything like her brother’s blue eyes and raven hair, then Miss Trentham would be nothing short of a beauty. She had never realised eyes could actually be that blue, outside the covers of a romance from the Minerva Press. Or that penetrating, as though they looked right into you and saw all the secrets you kept hidden… Oh, yes. He was Lord Braybrook right enough. And she had accepted a post as companion to his stepmother and a sort of fill-in governess. It must be a most peculiar household, she reflected. Most ladies of rank would hire their own companions and the governess.

She snorted. It was all of a piece with his arrogant lordship. Marching into her home as though he owned it. Taking up far too much of her parlour with his shoulders…why on earth was she thinking about his shoulders? It hadn’t been his shoulders that had forced Goodall to back down, it had been that stupid card with his name and rank on it. Lord Braybrook. A title and Goodall had been bowing and scraping his way out backwards. Where was she? Oh, yes. His arrogant lordship, telling her what to do, taking the beastly uncomfortable settle instead of the wingchair, taking the tray and moving the tea table for her— lighting a fire she could not afford, although if she was leaving on Thursday there was enough fuel to last.

At least she was warm now. It had been a kindness on his part. Of course some men were considerate, but she must not linger over it as though he had done it for her.

Drat him! Cutting up her peace, arranging her life to suit his own convenience, dismissing her concerns about propriety in the most cavalier way, and—

Well, he did come around in the end…

Only because he had to, or you wouldn’t have accepted the position!

Which begged the question: why—despite his desire to have her give Miss Trentham’s thoughts a more proper direction— did he still persist in thinking her a proper companion for his stepmother and younger siblings?

She had flown at him like a hellcat, been as rude as she knew how and argued with him when he showed a wholly honourable concern for her comfort and welfare on the journey to Hereford.

Why hadn’t he simply retracted his offer of employment and walked out?

And why was she even bothered about it? Why not do as he suggested and accept his money without argument? In a ladylike way, of course.

The seething, rebellious part of her mind informed her that she was going to have trouble accepting any of his lordship’s dictatorial pronouncements without a great deal of argument. Ladylike or otherwise.

In the meantime, due to his lordship’s rearrangement of her life, she had not enough time for everything. Certainly there was no time for pondering the odd feeling that she had just made the most momentous decision of her life. Or had it made for her. As for the ridiculous notion that Lord Braybrook was somehow dangerous—nonsense! Oh, she had no doubt that to some women he might be dangerous, but she had heard the scorn in his voice.

Believe me, I’ve no designs on your virtue.

That stung a little, but when all was said and done, she was a dowd. Perhaps a little more so than was necessary, but that was all to the good if it deflected the attention of men such as Lord Braybrook.

There had been that look, though, the feeling that he truly saw her, Christy, not merely Miss Daventry… She shut off the thought. Only a fool needed a lesson twice. The last thing she wanted was for him to notice her at all. Men seemed to have difficulty in comprehending when no was short for no, I don’t want to go to bed with you rather than no, you aren’t offering enough.

Crossly she pushed away from the door. She would not be sorry to leave this house. Once it had been happy enough, when Mama had been alive. But now it was filled with memories of nursing her dying mother. One must go on. And apparently, come Thursday, that was precisely what she would be doing.

As for Harry—was he mad? How could he imagine himself a suitable match for the Honourable Miss Trentham? A viscount’s sister, no less! The least investigation… She knew the answer of course: his Grace, the Duke of Alcaston. The Duke’s patronage had given Harry ideas dizzyingly far above his station.

Why could Lord Braybrook not behave like any normal man, forbid the match and see that the importunate suitor was denied the house? She had that answer as well; he thought it might drive his sister into revolt, and if his sister was as used to getting her own way as he was, then he had a point.

Unless… There was one way in which she might ensure Lord Braybrook could take that action without his sister uttering a word of protest. A single letter to his lordship would suffice. She looked at the bureau bookcase, hesitating.

Writing that letter would work, but at the cost of an appalling betrayal. Telling tales under a self-righteous cloak. And it was important for Harry to acknowledge the reality of his situation. Somehow she had to persuade him that his course of action was wrong. She needed to see him. Harry would ignore her letters to him. She must see him, try to persuade him of the wrongness of his intention to ensnare Miss Trentham or any other woman without telling her family the truth.

It might even ruin Harry if the truth were generally known. She wasn’t sure, but she could not take that risk. As a last resort she might have to tell the truth, but it would drive a wedge between them and she had no other family. None that she cared to acknowledge.

And there was another consideration—the money Lord Braybrook offered. She did have some money. Enough to manage if she were very careful, and prices didn’t rise. But there was little left over to hoard against illness or chilly old age. With this position, she could add to her meagre nest egg. Even if it were for a year or less, she would earn far more than she could in any other position, and she would save her keep as well.

She could pack up her books and take them with her. Braybrook had said his man of business would help; very well, she would ask him to sell the furniture bequeathed to her by Mama. It might not fetch very much, but every penny helped, and she was damned if she’d leave it for Goodall to sell on Harry’s behalf!

Accepting Lord Braybrook’s offer was the sensible thing to do. As long as she remembered her place. Separate. Apart. If only she could succeed in teaching Harry that lesson.

There was no real choice. She must go into Herefordshire and make Harry see the truth—that a greater gulf than mere money lay between the Daventrys and the Trenthams. If she failed, then, in the last resort, she must tell Lord Braybrook the truth herself.

Despite the fire warming the room, she shivered, imagining his disdain, the brilliant eyes turned icy. She stiffened her spine. It didn’t matter. There was no question of her being upset by his contempt.

That sort of thing only hurt if one committed the folly of allowing someone too close. A warning voice suggested that in breaching her reserve and triggering her temper, Lord Braybrook had already stepped too close. She must ensure he never did so again.

Chapter Three

Three days later an elegant equipage pulled up St Michael’s Hill to the Chapel of the Three Kings. Julian sat back against the squabs, still not quite able to believe what he had set in motion. On the seat opposite sat his valet, Parkes, stiff with disapproval, apparently determined to remain so for the entire journey. The news that he was required to sit inside, rather than on the box hobnobbing with his crony the coachman, had been ill received.

Not a chaperon precisely, thought Julian. For a young lady of quality, Parkes would be thoroughly inadequate. For the governess, however, his presence would dampen gossip. Besides which, Julian still felt uneasy about Miss Daventry. Something had sparked between them. Something dangerous, unpredictable. He found himself thinking about her at odd moments, smiling slightly at her stubborn independence.

He should have put her in her place, reminded her of the abyss between them. But that had been impossible with her cool façade shattered. They had spoken as equals. That must never happen again. No matter how much it piqued his interest.

She was just a woman with a temper that she had learned to control. Nothing more. There was no mystery behind the prim glasses that would not upon closer acquaintance fade to mundanity. In the meantime, it was safer to have Parkes, rigid and disapproving, on the opposite seat beside Miss Daventry. If nothing else, it would serve to remind her of the gulf between master and servant.

The carriage drew up outside the Chapel. Glancing out, he discovered Miss Daventry had foiled his plan to assist with her baggage. She was seated on one of a pair of trunks and accompanied by a female of indeterminate age and generous proportions. Julian wondered how the devil the pair of them had got the trunks up the street.

Miss Daventry had stood up. ‘Goodbye, Sukey. Thank you for your help. I wish you would let me—’

‘Oh, go on with you!’ said the woman. She shot a suspicious glance towards the carriage and lowered her voice to the sort of whisper that could cut through an artillery engagement. ‘Now you’re quite sure all’s safe? Can’t trust these lords. Why, only t’other day—’

She broke off as Julian stepped out of the coach. Miss Daventry, he was pleased to note, flushed.

‘I’m sure it will be all right, Sukey,’ she said, darting a glance at Julian. ‘Good morning, my lord.’

‘Good morning, ma’am. My valet is within the coach,’ said Julian, with all the air of a man setting a hungry cat loose in a flock of very plump pigeons. ‘I do hope that allays any fears your friend has.’

The woman’s eyes narrowed as she stepped forwards. ‘Aye, I dare say it might. If so be as he ain’t in your lordship’s pocket, in a manner of speaking. If you are a lordship an’ not some havey-cavey rascal!’ She set her hands on her hips. ‘I ain’t looked after Miss Christy this long for her to be cozened by some flash-talkin’ rogue! Why, only t’other day a chap persuaded a young lady into his carriage and had his wicked way with her. Right there in the carriage! An’ her thinkin’ it was all right an’ tight, just acos he had another lady with him. Lady, hah! Madam, more like!’

‘Ma’am, I assure you that I have no designs upon Miss Daventry’s person,’ he said with commendable gravity. ‘Her brother is known to me and my only object is to convey her to her new position as my stepmother’s companion.’

Sukey snorted. ‘Easy said!’

‘Sukey,’ said Miss Daventry, ‘I am sure it’s all right. Truly.’

Clearly unconvinced, Sukey stalked to the coach and peered in, subjecting the scandalised Parkes to a close inspection. She stepped back, clearing her throat. ‘I dare say it’s all right.’ She looked sternly at Miss Daventry. ‘But you write soon’s you arrive. Vicar’ll read it to me, like he said. And keep writing so’s we know.’

‘Sukey—!’ Miss Daventry appeared completely discomposed.

The older woman scowled. ‘Can’t be too careful, Miss Christy. You do like we said an’ write!’

‘Yes, Sukey,’ said Miss Daventry meekly.

Julian blinked. There was someone in this world to whom Miss Daventry exhibited meekness?

‘This is everything, Miss Daventry?’ he asked, signalling to the groom to jump down.

She looked rather self-conscious. ‘Yes. But one of the trunks is only books, so if there is not room—’

‘There is enough room,’ he told her.

The groom hefted one trunk into the boot along with the valise. The other trunk was strapped on the back.

Sukey came forwards and enveloped Miss Daventry in a hug. To Julian’s amazement the hug was returned, fiercely.

Finally Sukey stepped back, wiping her eyes. ‘Well, I’m sure I hope it’ll all be as you say. You be a good girl. Your mam ‘ud be real proud of you. You take care, Miss Christy.’

‘I will. You have the keys safe?’

‘Aye. I’ll give ’em to that agent fellow. Off you go, then.’

Ignoring Julian’s outstretched hand, Miss Daventry stepped into the coach and settled herself beside the valet.

Julian found himself facing judge and jury. He held out his hand. ‘Goodbye, Sukey. You may rest assured that Miss Daventry is safe.’

Sukey accepted the proffered hand, after first wiping her own upon her skirt. ‘I dare say. Miss Christy—Miss Daventry—she’s a lady. Just you remember that, my lord. I’m sure I hope there’s no offence.’

‘None at all,’ Julian assured her.

He stepped into the coach and sat opposite Miss Daventry. They moved off and Miss Daventry leaned out of the window, waving until they turned the corner and she sat back in her seat. Her mouth was firmly set, her expression unmoved. Yet something glimmered, trapped between her cheek and the glass of her spectacles. Julian watched, wondering if her emotions might get the better of her, but Miss Daventry’s formidable self- control prevailed.

Relieved she was not about to burst into tears, he performed the introductions. ‘My valet, Parkes, Miss Daventry. Parkes, this is Miss Daventry, who is to be companion to her ladyship and also assist as governess at times.’

Miss Daventry smiled. ‘How do you do, Parkes?’

‘Very well, thank you, miss.’ And Parkes relapsed into the proper silence he considered appropriate when circumstances dictated that he should intrude upon his betters.

Seated in his corner of the carriage, Julian picked up his book and began to read. There was no point in dwelling on the fierce loyalty Miss Daventry had inspired in her servant. Nor her obvious emotion at Sukey’s protectiveness. Of course Miss Daventry had feelings. Nothing surprising nor interesting in that. Her feelings were her own business. He had not the least reason to feel shaken by that solitary tear.

On the other side of the carriage Christy watched as his lordship disappeared into the book. She had not bothered to have a book to hand. If she dared to read in a carriage, the results would be embarrassing. Especially facing backwards.

She steeled herself to the prospect of a boring journey. There was no possibility of conversation with the elderly, dapper little valet. He had all the hallmarks of a long-standing family retainer. He would not dream of chattering on in the presence of his master, even if Christy herself did not fall into that limbo reserved for governesses and companions. She knew from experience that her life would be lived in isolation, neither truly a member of the family, nor part of the servants’ hall. Neither above stairs, nor below. An odd thought came to her of generation after generation of ghostly governesses and companions, doomed to a grey existence on the half-landings. Just as well, too. It made her preferred reserve far easier to maintain.

Her stomach churned slightly, but she breathed deeply and otherwise ignored it. It was partly due to tiredness. With all the work of packing up the house, she had scarcely had more than five hours sleep a night, and last night she had barely slept at all. She never could sleep properly the night before a journey, for dreaming that the coach had gone without her and she was running after it, crying out for it to wait, not to abandon her…

She wondered if she dared lower the window and lean out. No. It would be presumptuous, and she would become sadly rumpled and dusty. Not at all ladylike. She set herself to endure, leaning back and closing her eyes.

Leaving Gloucester midway through the second day, Julian knew Miss Daventry was not a good traveller. He had without comment lowered all the windows. Not that she complained, or asked for any halts. But he could imagine no other explanation for the white, set look about her mouth, or that when they stopped, she would accept nothing beyond weak, black tea. She hadn’t eaten a great deal of dinner or breakfast either.

He knew the signs from personal experience, only he had outgrown the tendency. There was little he could do about it, he thought, watching her. She was pale, and her eyes were closed, a faint frown between her brows. Oh, hell! ‘Miss Daventry?’

‘My lord?’ The eyes opened. He blinked, still not used to their effect. The shadows beneath them were darker today than yesterday. It shouldn’t bother him. Noblesse oblige, he assured himself. Nothing personal.

‘Miss Daventry, perhaps you might change seats with me?’

Somehow she sat a little straighter. ‘I am very well here, my lord. Thank you.’

He was not supposed to feel admiration—she was the governess- companion, for heavens’ sake! His voice devoid of expression, he said, ‘I think “well” is the last word that applies to you at this moment. Certainly not “very well”. Come, exchange places with me.’ Determined to expunge any misleading suggestion of personal feeling, he added, ‘I cannot sit here any longer feeling guilty.’

Blushing, she complied, scrambling across past him.

‘Thank you, my lord,’ she said, still slightly pink.

He inclined his head. ‘You are welcome, Miss Daventry.’ Detached. Bored, even. ‘Of course, should it be necessary, you will request a halt, will you not?’

She squared her shoulders. ‘That will not be necessary, my lord. I should not wish to delay us.’

He raised his brows. ‘I assure you, Miss Daventry, a brief halt will be a great deal more preferable than the alternative— won’t it, Parkes?’

The valet, thus appealed to, permitted himself a brief smile. ‘Indeed, sir. I’ve not forgotten how often you used to ask to be let down.’

Julian laughed at Miss Daventry’s look of patent disbelief. ‘Perfectly true, Miss Daventry. But I became accustomed eventually.’

A small smile flickered, and a dimple sprang to life. ‘I fear I did not travel enough as a child then. I remained staidly in Bath.’

‘Bath? I understood from your brother that your home had always been in Bristol.’ Where the devil had that dimple come from?

Miss Daventry’s pale cheeks pinkened again and the dimple vanished. ‘Oh. Harry was very small when Mama moved to Bristol. And I went to school in Bath when I was ten. When I was older I became a junior assistant mistress.’

She subsided into silence, turning her head to watch the passing scenery.

Julian returned to his book, glancing up from time to time to check on Miss Daventry. He told himself that he was not, most definitely not, looking for that dimple. He had seen dimples before. But, really, for a moment there, the staid Miss Daventry had looked almost pretty. Spectacles and all. And her mouth was not in the least prim when she smiled. It was soft, inviting…

There was something about her. Something that made him want to look again… The eyes. That was all. Once he became accustomed to them, she would have no interest for him whatsoever. In the meantime she was suffering from carriage sickness and it behoved him to care for her. No more. No less.

Reminding himself of that, Julian reburied himself in his book, only glancing over the top every ten pages or so.

Aware of his occasional scrutiny, Christy tried to ignore it, repressing an urge to peep under her lashes. Her heart thudded uncomfortably; the result, she assured herself, of having so nearly revealed too much. Her pounding heart had nothing to do with those brilliant eyes that seemed to perceive more than they ought. It wasn’t as if he cared about her, Christy Daventry. She was in his charge, therefore he owed it to himself to make sure she was comfortable. If she were not, it was a reflection on himself. He was being kind to her in the same way he would care for any other servant. Or his dog or horse. Admirable, but nothing to make her heart beat faster. Noblesse oblige. That or he was ensuring she wasn’t sick in his beautifully appointed carriage.

But the bright glance of his blue eyes was hard to ignore. She was infuriated to find herself drifting into a daydream where his lordship’s remarkable eyes were focused on her. And not because he was concerned she might be sick all over his highly polished boots.

Ridiculous! She knew nothing of him. Except that he was thoughtful enough to find a companion for his stepmother, kind enough to change seats with the carriage-sick companion, and sensible enough not to drive his sister into revolt. Heavens! She was rapidly making him out to be a paragon.

Lord Braybrook was no paragon. The lazy twinkle in his eyes, combined with unconscious arrogance, suggested he was the sort of man a sensible woman steered well clear of. Assuming he had not already informed the sensible woman that he had no designs on her virtue, as though the idea were unthinkable. And a very good thing too. Christy had a sneaking suspicion that when his lordship did focus his attention on a female, good sense might come under heavy fire.

Oh, nonsense. He was probably horrid on closer acquaintance, the sort of man who kicked puppies. Yes. That was better. No one could like a man who kicked puppies. Or kittens. A pity she was having so much difficulty seeing him in the role. Much easier to see those lean fingers cradling a small creature… rocking it.

She smothered a yawn. Such a warm day…rocking…like a cradle. No, that was the coach. It was beautifully sprung and she felt much better now, facing forwards. Far less disconcerting to have the breeze from the open window in her face and see the world spinning towards her and away, rather than just spinning away in front of her…rocking, rocking, rocking…

Later, some time later, she was vaguely aware of being eased down to the seat, gentle hands removing her bonnet and spectacles, tucking a rug around her, a light touch feathering over her cheek…a dream, a memory, nothing more. Christy slept, cradled in dreams.

She awoke in near darkness to a touch on her shoulder and a deep voice saying, ‘We are nearly there, Miss Daventry.’

Dazed, she sat up. Strong hands caught her as the coach swung around a turn. Coach? Where…? Blinking sleep away, she clutched at the strap hanging down, and the hands released her. Some of her confusion ebbed. This was not Bristol. She was in a coach, with Lord Braybrook and his valet. Why had she been lying down with a rug tucked over her? And where were her glasses? Everything was blurred.

Worried, she felt along the seat. They must have fallen off while she slept. And how dreadful that she had dozed off in front of Lord Braybrook and been shameless enough to lie down! And her spectacles were probably broken if they had fallen to the floor.

‘Miss Daventry—is something amiss?’

She flushed. ‘My spectacles must have fallen off. I can’t see without them.’

‘Of course.’

He reached into his pocket and drew out a small object, offering it to her. Confused, she reached for it and he placed it in her hand. Immediately her fingers recognised her spectacles, wrapped in a handkerchief.

‘I thought they were safer in my pocket,’ said his lordship.

Her fingers trembled slightly as she unfolded the handkerchief, shaken by a memory of gentle hands making her comfortable. Had her dream not been a dream? Had he laid her down on the seat and removed her spectacles and bonnet? And tucked the rug over her? She swallowed. He must have. But the caressing touch on her cheek had certainly been a dream. Hadn’t it?

‘Thank you, my lord,’ she said, putting the spectacles on. The darkening world came back into focus. ‘You are most kind.’ She schooled her voice to polite indifference. His noblesse oblige again. If she remembered that, good sense would prevail. Not the foolish dream of tenderness. She handed him the handkerchief.