Полная версия

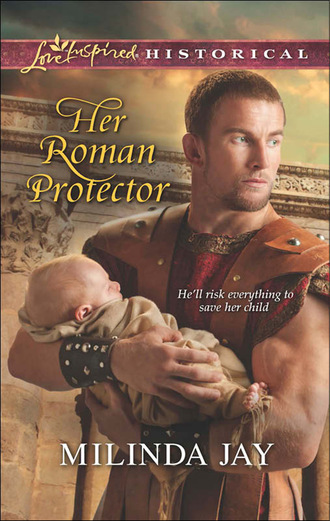

Her Roman Protector

Annia let out a small yelp when he pretended to slap her face, and the men circled around them and laughed.

“Thank you, sirs,” Marcus said, putting a hand over Annia’s mouth. “This little one has run away one too many times. I may have to sell her at market.”

“I’ll buy her,” the blacksmith said. “How much will you take?”

“Well,” Marcus said, “she actually belongs to my father. But give me your name and where you conduct your business, and you will be the first one to know when we put her up for sale.” Marcus shot the man a charming smile. “I would shake your hand, but as you can see, mine are quite full.”

The men parted to let him through.

“Suetonius Rufus,” the blacksmith called. “My shop is three streets over near the baths. I’m a blacksmith,” he continued.

“Thank you, sir,” Marcus said. “I will remember you by your red hair.”

The man touched his hair, and Marcus pulled Annia safely away around the corner, out of the man’s line of vision.

When they reached the safety of the baths, Marcus took his hand off her mouth.

“You did me no favors,” she spat. “I would have escaped on my own.” And she unsheathed a tiny dagger to prove it.

“Really?” he said, pulling her into the dark recess of the inner fountain. “Well, domina, next time, I will let you defend yourself.”

She was shaking and held the dagger to his stomach. “Where is she?” she hissed. “Where did you take my baby?”

“Put the dagger down, and I will tell you,” he said.

Chapter Two

He must take her for a fool. How many other women had this handsome man lured into believing he was saving their babies, when in truth, he was selling them into slavery?

She had to be very careful with this one. He was strong, he was smart and he seemed determined.

Well, she had fought fierce warriors in Britain, hadn’t she? Surprising them with her strength?

He would not be surprised. He had already gauged her strength. She would have to be very clever with Marcus Sergius Peregrinus. Very clever indeed.

“So tell me,” she said, sheathing her dagger, “where is this place you have my baby?”

He looked into her eyes, gauging them for sincerity, she suspected. “If you will come with me, I will show you. I don’t have much time. I have to get back to my men soon.”

“Ah,” she said. “Well, don’t let me keep you.”

He cocked his head, a question. “You are coming with me, yes?” he said.

“Certainly,” she said, trying to keep the sarcasm out of her voice. “How else could I get to my baby? Only you know where she is.”

They walked civilly, side by side, down the dark street. It was a few hours before dawn, and the streets were now quiet. Even the merchants’ carts had stopped, having already delivered their wares.

The only light came from the uncertain moon and the pitch-smeared torches illuminating sacred images at a few street corners and crossroads.

She didn’t trust this man. She knew better than he where her baby was. He had taken her to the place of exposure where the slave traders circled like hawks. Annia meant to get there.

She had to get away from him first.

The silence was broken by the cascading water of a neighborhood fountain. When they reached the fountain, the statue of a small boy—his arms reaching out in supplication, a stream of water flowing from his mouth—was illuminated by a single flame placed strategically at the water’s edge.

During the day, this same fountain was busy with women, children and slaves taking turns filling their wash buckets and water jars to carry back to their homes.

But tonight, it was eerily silent, the only sound the soft rush and gurgling of the water.

“Are you thirsty?” Marcus Sergius asked.

Annia was thirsty, incredibly thirsty. She ignored his offer of help and reached up to the trickling water, cupping her hands and drinking deeply.

Marcus waited for her to drink her fill and then reached up to drink.

When he did, she took her chance. She ran.

Apparently, he had expected her to run and he caught her before she even reached the pavement at the edge of the fountain.

They both went down on the hard stone, he on his back and she atop.

He grasped her arms, and she kneed him in the stomach. She pulled away and unsheathed her knife.

Both on their feet, they circled each other. His breathing was heavy, as was hers.

She jabbed, but he pulled back and then reached for her knife.

But she was quicker.

His eyes widened. She was used to it. He hadn’t expected her to be this good with a weapon. What proper Roman matron could wield a knife with such dexterity?

The look on his face now was one of respect. What had he recognized? Before she could move again, he had countered. He seemed to know exactly what she was going to do before she did it, and now he was holding her wrist, tightening his grip until she was forced to drop the knife.

“Trained in the wilds of Britain, as well?” he said, his voice ragged.

Now it was her turn to stare wide-eyed at him.

Fury strengthened her. She poised to run as soon as she had the chance.

“I would rather not do this,” he said, “but you leave me no choice.”

With the dexterity of a battle-trained legionary, he caught her wrists in a leather thong and pulled it securely. Her wrists bound, she was forced to walk humbly behind him.

“Where are you taking me?” she asked. “I know your type,” she said. “Ready to make a gold coin off anything possible.”

She could tell from the set of his shoulders that she had angered him. He said nothing.

“I have money,” she said. “I can buy my child from you. I can get you all you need.”

“I don’t want your money,” he said.

“I’ve yet to meet a soldier who didn’t want money, who wasn’t willing to buy his way to the top so that he could stop fighting and send other men in to do the bloody work.”

At this, he turned on her, yanked the leather cord down, savagely squeezing her wrists so tightly that tears smarted in her eyes. He pulled her close.

“You, domina, have no knowledge of what you speak. Close your mouth, and let me take you to your baby before I change my mind.”

The struggle in his face was palpable. She had struck a chord in this man. A deep one. The pain in his face spoke of unspeakable horrors. She was embarrassed and ashamed, but she was not certain why.

He was her enemy. He had her tied with a leather thong. Why did she feel such compassion for a man who had sold her baby and was now leading her to be sold?

She almost apologized but held her tongue.

She had no choice but to allow him to lead her to the place of enslavement. Perhaps, if she was blessed, she would at least be enslaved with her baby.

They stopped in front of a row of shops separated by a high wooden double door replete with bronze doorknobs.

Annia recognized the front door of a grand villa.

In the center of each door was a giant bear’s head holding a large ring in its mouth to be used as a knocker.

A bear’s head on a Roman door? Odd. Usually, the door carried a wolf, or even a lion, but rarely a bear.

Was it a sign? In Britain, bears meant strength and survival.

Characteristic of very wealthy Romans, this villa rented its street-front rooms to various shop owners, their signs barely visible in the darkness. There were four shops on either side of the door. Annia leaned back to see how many floors this villa held.

Three stories high. She guessed that the shop owners lived directly above the shop, and perhaps the floor above that was rented out to other tenants.

She had been the mistress of just such a villa.

Marcus lifted and dropped the knocker.

It sounded her doom.

Immediately, the door opened.

Annia felt her fate closing in on her. Why? Why had Janius been so determined to get rid of her baby girl? Did he fear having to provide a dowry for her? Did he fear he would have to divide all his new wealth with his youngest daughter?

And if he was so quick to get rid of this newborn, what would keep him from getting rid of their two young sons?

Surely Janius would not harm his own flesh and blood.

And yet he knew this newborn child to be his, and he had no qualms about exposing her.

Annia closed her eyes and whispered a prayer. Protect me, Lord. Protect my child.

“Mother,” Marcus said, his voice registering warm surprise. “Why are you up?”

“I had a bad feeling about this one,” a woman’s voice responded, “but you have brought her home safely?”

Home? Annia wondered. Home for whom? But she had no more time to ponder this question.

“Annia,” Marcus said, “I would like for you to meet my mother, Scribonia.”

Annia felt slightly off-kilter. Such a formal greeting for a would-be slave?

And Scribonia? Wasn’t that the name of her midwife? Surely not the same woman.

When Marcus moved out of her way, the lanterns lighting the atrium were directly behind the woman, blinding Annia and reducing the woman before her to dark, shadowy outlines. Annia could not make out the woman’s face or even the color of her clothing. She seemed tall, taller than Annia, and very thin.

Annia couldn’t tell if this woman was her midwife or not.

The woman seemed to be reaching for her.

Annia was frightened. What did the woman want of her? She wished that she could see better. She glanced at Marcus, but he had already moved forward, into the atrium behind his mother. He brushed past her.

“I must go now, Mother,” he said, and kissed her on the cheek. “Already, I fear the men may have left their duty and gone home.”

“Be careful, son,” his mother said, and then turned her attention to Annia.

Annia recognized the voice now. It was the midwife. She held something in her arms, and she was reaching to hand it to Annia.

When Annia held her hands out in response, the soft bundle placed there was none other than her baby girl.

Marcus gave a satisfied nod before closing the door behind him.

* * *

The night was black, the black that happened just before dawn. Marcus knew he’d better hurry if he was going to catch his men at the eating place before it closed.

Why had she been so stubborn? Why hadn’t she believed him? In spite of himself, Marcus was confused. He liked to be trusted. She hadn’t trusted him.

But then again, why should she have trusted him? He came into her house in the dead of night demanding to take her baby to be exposed.

How was she to know that he really didn’t mean to do it?

Could she learn to trust him?

Why did he care? What did it matter? His brain felt twisted in knots.

He couldn’t stop thinking of her.

He was back in Rome and looking for a wife, not the divorced mother of three children.

But there was something about the woman, something fierce, something beautiful, something that made him yearn to protect her.

It was late, and he was tired. Otherwise, he wouldn’t be thinking such thoughts.

When he arrived, his men were waiting as instructed. They were the last customers.

Trained to be as faithful as Roman soldiers in the field, the Vigiles sat around a long table, their mead cups before them. When one nodded, his neighbor clouted him awake.

The penalty for sleeping on guard in the field was death by stoning. The men were loyal to one another as well as to their sergeant.

“Sir,” one of his men said, “we feared for you.”

“We thought to come after you,” another broke in.

“But the order,” a third said, “was to stay here until you returned.”

They looked up at him hopeful, fearful.

The Roman army was built on fear, and these young men longed to be a part of the army.

Marcus felt for them. He remembered the same longing for adventure, the taste for discipline, the desire to be a part of something that would allow him to prove himself.

And get away from his family.

Wasn’t that the dream of all sixteen-year-old boys?

“You’ve done well, men,” Marcus said. They tried not to smile, but the boy in each of them couldn’t help being pleased. “Let’s go.”

They gathered their leather coin purses and strapped them to their belts.

Marcus paid Gamus the merchant, and his close friend. “Thank you, Gamus. I apologize for the long night.”

“Ah, Marcus. I am happy to help you. But before you go, step back here. There is something I’d like to show you.” The merchant waved him into a back room, and Marcus sent the men outside, where they lined up in close formation.

Marcus nodded and waited for him to speak. He knew Gamus had something important to say.

“What I’ve heard is not good for us, Marcus,” Gamus said, his voice hushed so that Marcus had to lean close to hear. “There is talk that the emperor wants the Jews out of Rome.”

“We are not Jews,” Marcus replied. “We are followers of the Christ.”

“Ah, but Claudius doesn’t know that. He sees us all as one big group of rabble-rousers. When the Jews go, I fear, so must we.”

Gamus straightened another amphora, pulling his cleaning cloth from beneath his belt.

“But where? Where is it safe? The empire stretches past knowing,” Marcus said. He had heard this rumor himself, but had thought it just that.

Gamus’s words frightened him. What about his mother? What about her villa full of rescued babies? How could they possibly be moved?

“It seems he merely wants us out of Rome,” Gamus replied.

“I see,” Marcus said, somewhat relieved. At least they would not be banned from the empire. “Do you have a place to go?”

“Yes, I have a country estate in Britain,” Gamus said, “a gift granted by Claudius for my long years of service in the army. My wife and I would like to retire there one day. Perhaps sooner rather than later. And you? Where would you go?”

The thought of leaving Rome was something he did not want to consider. He had just returned to the city of his birth after having been gone for twenty long years of service. He had a dream to stay here, to gain enough power to bring peace to his city.

“I don’t know,” Marcus said. “My father would love to move back to Britain, as well. He was happiest there, I believe. I would rather stay here. I believe I can be of the most use right here.”

“That may be so. Well, lad, perhaps the emperor will leave us alone. We are a peaceable people.”

Marcus agreed. It was the very peace of his faith that made him long to become a prefect.

“Well, my friend, thank you for entertaining my men.”

“Is the baby safe?” a female voice boomed, startling both men.

Gamus’s wife appeared in the stairwell next to the storage room. She was wrapped in a white linen robe, her hair mussed from sleep. Her warm smile, round, rosy cheeks and jolly disposition seemed at odds with her booming voice.

“Yes, Nona, the baby is safe.” Marcus smiled up at the kind woman.

“Good, good, then,” she said, clapping her hands together. “Now see your men home and come back here. I have dough rising, and by the time you get back the bread will be baked.” Her eyes sparkled and Marcus had to say yes, and pray that her voice didn’t wake everyone on the street.

“Thank you, Nona. You always take care of my stomach.”

“Well, child, you need your strength to traverse this wicked city. You must walk many miles each night.”

“Not so many,” Marcus said.

Nona smiled and retreated up the stairs. “See you in the morning light,” she said.

“How are the rescues going?” Gamus asked. “I worry about you, lad.”

“My mother’s villa is full to bursting,” Marcus said. “I’m not sure she can take any more babies. Tonight might have been my last rescue.”

“Good,” Gamus said. “I don’t like the danger for you. Too easy to be seen. Your mother has done a good thing all these years rescuing those poor, abandoned infants and trying to reunite them with those mothers who did not want them exposed. But she is only one woman, and Rome is a large city with many abandoned babies every day.”

“She only rescues the ones she delivers and knows the mother’s heart to be broken when the father orders exposure for lack of dowry money or some perceived weakness,” Marcus said.

“I know, lad, but it is becoming dangerous for you.”

“I do worry that my men are growing suspicious,” Marcus said.

“Not to worry. I give them as much mead as they want.”

Marcus laughed. “Thank you, my friend.”

“Good night, then,” Gamus said.

The night was spent and the gray dawn of morning rose around them as Marcus led the men down the street and back to their garrison.

The hobbed nails of their boots pinged against the stone as they marched into the early light.

The men were good, but what was he doing here leading a group of eight firefighters on a mission to keep the city safe, night after night?

He had a plan. He just prayed it worked. He had distinguished himself in Claudius’s wars in Britain. Serving under General Vespasian in the II Augusta Legion, he had fought to secure the southern and midland territories, but the north and west were yet to be subdued. He had been offered land in Camulodunum, which he accepted, but chose to continue his service in Rome rather than retiring after the requisite twenty years of service in Britain. Aside from despising the cold, damp climate of Britain, he had ambitions. Ambitions that could only be fulfilled in Rome. Ambitions that he hoped this Galerius Janius could help him fulfill.

“Sir,” one of the young men said, snapping Marcus out of his deep rumination.

They had reached the wealthier section of the city. Here the doorways were wider and the walls marble. The shops hid grand villas behind their walls whose owners rented the street front of their villas to merchants. This served a dual purpose. Besides bringing in a tidy sum in rents, the shops buffered the noise of the streets away from the living quarters. The villas were veritable oases in the heart of the city.

The sun’s rays dappled pink upon the neatly swept street and sidewalks, quiet but for the sound of iron bolts being opened and boards being stowed away, marking a new day for the shopkeepers.

As it was too late for shop carts and too early for chariot traffic, the street itself was deserted.

Except for Galerius Janius, who stood in the middle of the street before his massive villa, waiting.

“Marcus Sergius?” Janius said, stopping the Vigiles with an upraised hand. “My friend,” he said. “And how goes it with you this fine morning?”

His well-fed belly hung over the edge of his tightly belted tunic, and he balanced his carefully wrapped toga imperiously over his arm.

“Well, sir, and you?” A prickle of doubt ran through Marcus. Perhaps he should not have trusted this man. Had he been followed? Had someone seen that the baby was safe in her mother’s arms rather than in the place of exposure?

Marcus couldn’t imagine what had made Annia marry the man standing before him. Perhaps she had little choice. Perhaps it was a marriage arranged by her father.

Perhaps she had reason for the adultery of which she was accused.

“Yes, yes,” Janius said, measuring Marcus and then his men. “A fine crew you’ve assembled here.”

Marcus nodded. “Yes,” he said, “the emperor has very clear guidelines for the Vigiles. They must be able to fight fires as well as keep order in the streets. For this reason, the requirements of service are the same as for a legionary.” Why did he feel the need to defend his men against Galerius Janius?

“Really? How quaint,” Janius said. “Well, if you would like to come inside, I can pay you for your troubles.”

Janius headed into his house, confident that Marcus would follow.

When Marcus didn’t move, Janius turned. “You did follow my orders, did you not, soldier?” His eyes narrowed, and he looked more carefully at Marcus.

“I did,” Marcus said. Something in the window above caught his attention. But whatever it was moved away as soon as Marcus looked up.

“And was your little mission successful?” Janius asked.

“It was,” Marcus said, though the words were bitter in his mouth. To give this man satisfaction was more difficult than he imagined. He wanted to paint the true picture in painful detail for this man.

The baby Janius had ordered exposed, the baby Janius wished dead or enslaved, was safely ensconced in a villa even more lovely than this, being nursed, no doubt at this very moment by Annia herself.

What he had done was dangerous. If Janius discovered the truth, Marcus’s hopes of becoming prefect, or even an important member of the Praetorian Guard, would be destroyed.

“And was the little beauty snatched up by slave traders or eaten by dogs?” Janius snorted and laughed.

“I didn’t stay to see,” Marcus said affably, clutching his sword.

“Well, good, then,” Janius said. “The less offal on the streets of Rome, the better. I have no intentions of supporting an unfaithful woman’s spawn.”

Marcus’s hold on the gladius tightened. Janius noticed.

“Armed for warfare, are we?” he asked.

“Just habit, sir,” Marcus said, his voice affable still. “As you said, the less offal on the streets of Rome, the better.”

Janius’s eyes narrowed.

“Well then,” Janius said. “Good day.”

“Good day to you, sir,” Marcus said.

“Oh,” Janius said, turning around. “Here is a coin for your troubles.”

“No, thank you, sir. It was my duty. The baby had been ordered exposed at birth and was not. The law was broken. My men and I went in to correct a wrong. It is my job to be sure that the law is upheld.”

Janius looked at him, his head cocked to one side, as if he was gauging the truth of his answer.

“What a fine man of the law you are, then,” Janius said, the words dripping with sarcasm. “I will still keep my end of the bargain and recommend you for a promotion in rank.” His smile was wide, his eyes narrow.

Marcus’s expression was impassive.

The men waited as Janius turned again and walked into his house. As soon as the door closed, however, Marcus looked up and caught sight of two little brown eyes peering at him from the open window above the shops.

Clearly, this was Annia’s son. He had the same small features, the dark eyes, curly hair. He looked nothing like his father.

And based on the look of horror on his face, the little boy, who could be no more than ten years old, had heard the entire conversation.

Marcus wanted to tell the boy his baby sister was fine and his mother, too. But he had no way of doing so.

And the boy had clearly marked him as the enemy. The one responsible for taking his baby sister to her death.

Chapter Three

The woman, Scribonia, led Annia to her room. They climbed two flights of narrow wooden stairs, above the shops, above the shopkeepers’ quarters, into the very top floor of the villa.

Both Annia and Scribonia wore soft leather indoor sandals. So silent were their footsteps that Annia could hear the gentle breathing of babies as she walked by the rooms leading to hers.

Scribonia held her lantern high, parting the curtain that formed the door of the small room so that Annia could see her way in.

The room was bare but for a cradle, a small bed and a table.

Scribonia lit the candles in the bronze wall sconces and one on the small table beside the narrow wooden bed. Candlelight flickered on the mother-of-pearl shells inlaid in the wood, and played on the rich red damask bedcover.

It smelled pleasantly of rosemary, and brightly painted murals covered the walls. Annia would have to wait for the morning light to make out the images.

“We’ll talk in the morning,” Scribonia said. “You and your little one have been through quite the ordeal. I hope you find peace and rest here.”