Полная версия

‘I do, in fact.’

He picked at the ruined sleeve of her coat. ‘Go buy a replacement for your torn coat and charge it to the Guild. Then we can leave this place. But don’t wander.’

I’ll wander off however I like, you insipid creature, Arden thought ferociously, her anger a physical pain that could not be soothed by her speaking the curse aloud, so remained inside her like a swallowed coal that did not cease to burn.

Arden picked in despondent indecision at the mess of fisherman’s clothing with gloves too fine for a village on the edge of nowhere, until her arms smelled of fishwax and linseed oil.

She had wasted so much time shut inside Mr Justinian’s decaying baronial estate, and at her first breath of liberty all she’d been allowed to see were street-fights and offal sellers. Despair – always so close and so suffocating – had fermented in her time under curfew. She had heard the domestic staff talk behind closed doors or under stairs. To them, Arden Beacon was not a professional guildswoman sent from the great ports of Clay Portside. She was merely produce fatted up for the eventuality of Mr Justinian’s bed.

‘A devil’s curse upon you, Mr Justinian,’ she said beneath her breath, tossing aside a scale-speckled pair of trousers, ‘and curse you, Mr Lindsay, for—’

The bronze flash caught her by surprise, stopped at once the bleak train of her thoughts. What imagination was that, her seeing such a thing in all these stained linens and thistle-cottons?

Arden dug in deep again and disinterred her find – an odd, slightly sheened garment – out from the knot of unwashed rags.

She raised to the day a thing that in her hands made no sense.

A coat. A stout, utilitarian coat cut for a female worker of hard ocean climates. Not too long in the hem though; no loose fabric to foul a hurried journey up stone steps in a high storm. A thing rightly made of old canvas and felted wool, worn on a body until it fell to pieces.

But the fabric …

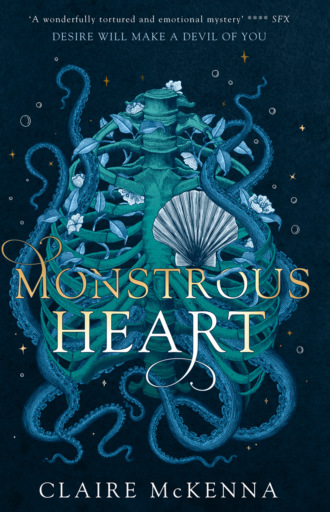

Arden had to rub the collar with her fingers, make certain her earlier fall was not causing her to see wonders. There was only one creature alive that could supply such a hide. Leather as bright as an idol’s polished head and with a crust of luminescent cobalt-blue rings across the arms and yoke. Subtle grading to black when it hit the light just so.

She turned the coat around and her breath caught. She had not expected the fabled kraken crucifix, the terrifying pattern of a sea-monster’s crest. By all the devils of sky and blood, you’d have found its likeness only in a Djenne prince’s wardrobe in Timbuktu, not a filthy rag pile at the edge of the world, and yet here it was; hidden away with thrice-mended broadcloth trousers and sweaters that were more knots than knits.

Before Arden could inquire about the article, her benefactor already had his hand about the coat’s collar.

‘Let me put that aside for you,’ Mr Justinian said and, without asking, slid in between her and the table, ready to yank Arden’s prize away. ‘This is not suitable.’

Despite her relatively short stature, and the dark, fragile air of over-breeding about her, Arden was no pushover. Growing up within the labyrinthine map of the capital city docks, one learned in the hardest of ways those streetwise traits anybody needed to survive. She saw the snatch coming in Mr Justinian’s beady eyes before he made his move, and quickly secured the coat within her strong lantern-turner’s hands.

‘No, Mr Justinian. I wish to buy it for myself.’

‘These wares are filthy. Look at them. Fish-guts and giblets. You are required to own a new coat to work the lighthouse, not cast-offs. As Coastmaster of Vigil I will have a fine plesiosaur leather coat made for you and sent from Clay Capital.’

‘I am not fulfilling your list by this purchase, Coastmaster Justinian. This coat is for my –’ she doubled down on her grip ‘– personal use.’

‘I’m telling you, you do not want it!’

He yanked harder, with enough force to pull Arden off her feet had the trestle corner not caught her thigh. She wedged herself deep into the splintering wood and hung on for grim life. Her ribcage groaned from the earlier trauma, sent sharp currents of pain through her chest, but still she held on.

‘No.’

‘Let … it …’

‘No, sir, no!’

They struggled for a while in stalemate, before he gave in with a hissed curse.

‘Keep the disgusting thing if you must,’ he said, tossing his end of the coat down. Arden heard the snarl under his disdainful words. ‘It is only a murdered whore’s garment anyway.’

2

A whore clothed herself

‘A whore clothed herself in this rag,’ he concluded with caustic passion. ‘A bitch who lay down with an animal and got herself killed for it.’

His curse words spoken, and with God having not struck him from the face of the earth for saying them, Mr Justinian shoved the trestle table once for emphasis, then stalked off across the town square towards the Black Rosette.

Arden exhaled, prickling with both triumph and remorse. She had won something over Mr Justinian, but at what cost?

The jumble seller, a stout grey-haired woman with the pale vulpine features of a Fictish native, remained cheery in the face of Arden’s dismissal.

‘You’ll get used to the muck and bother here, love. Once our Coastmaster gets a pint of rot into him, all will be back to normal.’

‘I must apologize,’ Arden said with forced brightness to the jumble seller. ‘Ours was not a disagreement we should have made you witness to.’

‘The young Baron is correct about the krakenskin, I’m afraid.’ The woman shook the violet threads of ragfish intestines off a pair of trousers that looked identical to the ones she herself wore. ‘The coat is a cast-off and completely unsuitable for any purpose.’

‘But it’s hardly used. I need a wet-coat to work the lighthouse. Only krakenskin could reliably stand all the weather that the ocean might throw at it.’

‘The lighthouse? You mean Jorgen’s lighthouse?’ The woman shifted her now-nervous attention over Arden’s shoulder. The horizon behind the town was mostly obscured by fog, but a good five or ten miles away as the crow flew the land curved into a hooked finger of stone. At the very tip of the promontory a granite tower stood erect as a broken thumb, a single grey digit topped with a weakly flashing light.

‘I am Arden Beacon, Lightmistress, Associate Guildswoman and Sanguis Ignis from Clay Portside, the traders’ city of Lyonne,’ Arden recited, still unfamiliar with her official titles. She held out her gloved hand. ‘I have come from Clay Portside in Lyonne to take over the lighthouse operation from my late uncle, Jorgen Beacon.’

‘A sanguinem?’ The woman frowned at the offered hand. ‘All the way out here?’

‘It’s all right,’ Arden said. ‘Touch doesn’t hurt me.’

Still cautious, the woman shook Arden’s hand timidly, her eyes still on the pony-plantskin gloves, so fine compared to the ubiquitous bonefish leather of the coast. Was not the gloves she minded, but what lay under the gloves that gave the woman pause. The coins. The little metal spigots that were both symbol and necessity of her trade.

Arden did not take offence. The reaction would be the same in Lyonne, among the commonfolk. The woman was gentle, and released her quickly.

‘Oh, I wasn’t minding your hands, dear. I was surprised that Jorgen was replaced so quickly when we could have well put a distillate lamp in there and be done with all the sadness.’

‘The Guild is very protective of its properties. That flame has been kept alive by sanguis for centuries, and they’d not likely stop now. Anyhow, what is the price of the c—’

‘Now that you say it,’ the woman interrupted, ‘I see the resemblance to Jorgen in you, that Lyonne high breeding, so elegant.’ She simpered a little, trying to curry favour with a rich woman from the hot North country. A rich sanguis woman, possessed of esoteric skills. ‘I am Mrs Sage. My husband is both apothecary and doctor in our town centre.’ Mrs Sage waved towards a rude row of wood and brick that even in Clay Portside would have been considered little more than ballast shacks. ‘We were told of Lightmaster Beacon’s passing, and that a blood-talented relative would soon replace him from the North, but … We expected a brother.’

‘All my uncle’s brothers have permanent Lightmaster positions in Clay Portside,’ Arden explained, annoyed that she would now have to have this conversation, and justify her sex, again. In Lyonne there would have been no question of her capabilities – labour was labour, regardless of the source. ‘I was the only one not contracted to any gazetted navigation post, and the Guild requires a sanguinem to crew their stations, so …’ She shrugged. ‘The Seamaster’s Guild requested that the Portmaster of Lyonne provide someone of the talent to take his place. So here I am. Buying a coat—’

‘Just like that?’

‘Well, the Seamaster’s Guild does have to administrate a lot of coastline. I cannot shirk a duty.’

Mrs Sage shook her head that Arden had not questioned such a direction. ‘It’s not right, a woman sent out to those rocks alone …’

‘The Portmaster of Clay is also my father,’ Arden said with a theatrical display of generous patience at Mrs Sage’s concern, so desperate was she to conclude this sale. ‘He understands more than anyone what my abilities are. He also understands that if there is not a Beacon at that lighthouse, it will go to a Lumiere or, God forbid, a Pharos, and,’ she stopped to give the most forced of smiles, ‘ignis families are very competitive for those positions offered us. It would break his heart for our family to lose another lighthouse post.’

‘Still. It pains me to sell you this coat, Lightmistress Beacon. I must refuse.’

Arden saw the coat sliding away in the manner of a barely glimpsed dream. She clutched it tighter.

‘Then why have it for sale if you won’t accept my purchase?’

Mrs Sage smoothed a sou’wester out upon its pile. Her red, chapped hands rubbed the linseedy surface of the rain hat. ‘I was hoping one of the ambergris merchants from Morningvale might buy it today, and take it far away from here. Sell this garment for a profit in a city where nobody knows its source. The young Baron was correct. The woman who owned this coat is dead.’

Murdered whore. Coastmaster Justinian had delivered the words with such venom, meant to hurt with all the force of a slap. Why had it concerned a Coastmaster so much, this discard on a rag-trader’s table?

‘Poor girl. The wife of the brute who killed her,’ Mrs Sage continued. ‘When her corpse was at last recovered from the water over yonder, all that remained was her scalp of golden hair and this coat, washed up upon the harbour shore.’ She tilted her chin towards Vigil’s small, pebbled waterfront, lying a short way down the rotting boardwalk. ‘Perhaps it was merciful, after all those months she suffered in the bed of a monster, that death should claim her so she might not suffer any more. But still, what an end. Slaughtered, and your meat used as a fisherman’s bait.’

Mrs Sage sounded so resignedly matter-of-fact at such an ignominious and unlikely method of dying that Arden couldn’t help but snort a laugh at her story.

The woman glared at Arden with brittle offence. ‘How else do you think the fisherman calls a sea-devil up from the deep by its own volition, to harvest it for such a fine leather, eh?’

And Arden saw then, the true price of the coat would be in her providing Mrs Sage an audience for a tale, a story that by the aggressive delight in her rheumy eyes was a particularly unpleasant one.

Mrs Sage dipped in close to Arden. Her breath stank of fish chowder and dandelion root.

‘These abyssal monstrosities, the kraken, the maris anguis and monstrom mare, they can only be compelled to surface by human meat. The fresher the better. They are drawn by gross desires and mutilations. There’s only so much of a slaughterman’s own body he can give. A toe, a finger, a slice of tongue or a testicle, hmm?’ Mrs Sage sucked her lined lips in thought, imagining the kind of man that would take a blade to himself for his profession. ‘An eye, a hand, a penis most probably, for in what world would anyone fornicate in consent with such an unholy creature as a man who feeds himself in fragments to the sea?’

‘I don’t—’

‘Yes, was him that killed his poor young wife for profit, slice by agonizing slice, and the coat made to clothe her, and remind her just what her sacrifice brought. What other worth was she to him? He had not the tool with which to fuck, and from that lamentable position her life was foreshortened indeed.’

Arden recoiled, taken aback by the salacious details of Mrs Sage’s story. ‘Ah, all right then, thank you for the, um … providential lesson.’

‘Was no lesson. Was caution, Lightmistress.’ Her eyes widened. ‘Was warning.’

Having exhausted her social resilience, Arden hurriedly dug into her purse and took out every note inside it, a wad of Lyonne cotton-paper bills that were not legal tender in Fiction, but all she had. Shoved them at Mrs Sage.

‘Here, here, take this money. I’ll make sure I give this coat a proper new life.’

Mrs Sage smiled and made motions of pious refusal, then took the money anyway. Her tongue pushed through the gaps in her teeth. Both pity and triumph she showed, as she made her announcement.

‘But you are still in the old life, Lightmistress. T’was for that reason I hoped you’d be male. If you are bound for the old lighthouse, then see that murderous hybrid of man and monster over there?’

Mrs Sage pointed past the grey haggle-hordes of the market plaza. Beyond the ice-baskets, one figure walked apart from the fishermen, shrugging into the same copper-black-coloured garment that Arden held in her hand. The man from the tavern fight. The demon. The victor.

Next to him, a handcart without a horse. Upon it was laden the raw, bleeding tail of a leviathan.

‘See that one? Mr Riven, he goes by, the monster of Vigil. That, my poor dear, is your new neighbour.’

3

Oh dear

‘Oh dear,’ Dowager Justinian said, her thin mouth drooping further once she saw Arden Beacon on the afternoon of her market adventure. ‘I didn’t quite believe my son when he told me of what happened this morning. You got the Rivenwife’s coat.’

Arden brushed the perpetual wet from her dress. ‘Was Mr Justinian terribly upset? I rather let him go his own way afterwards.’

‘I had not the chance to ask my son his full opinion,’ the Dowager said. Her eyes darted evasively behind her black gossamer veil. Dead a full decade her husband had been, and yet she still wore the same silks as for a planned funeral march. ‘I have been busy today.’

The Dowager was a thin, regal woman who may have once been warm in her beauty and generosity. Years on Fiction’s bleak coast had turned her sallow. The jewellery which she wore upon her constant uniform of black mourning had more in common with dull chunks of quartzite than the diamonds their settings suggested.

‘Well, there’s not much that can be helped, you weren’t to know about the histories of our town. I’ll have tea brought to your room.’

‘Thank you. I’d like tea.’ Arden noticed a small pile of correspondence on the sideboard. ‘Are there any letters from my family?’

‘Not since the ones from last week. The mail is slow, here.’

There were however some postcards from some old academy friends, mostly of mountains and chalets in daisy-meadows, for the summers were hot in Clay and those who could afford to escape to alpine hostels, did. Arden read the brief messages with a combined muddle of gladness and envy, and doubted finding any similar image to encapsulate Vigil when she wrote in return. Maybe a heavy-set fisherman in gumboots, waxed overalls and a gigantic cable-knit sweater, standing by a wicker basket of headless eels.

The Dowager followed Arden up the creaking stairs of Manse Justinian. The estate house had been built on an escarpment of basalt, and by its position looked down upon the town and much of the shaggy scrub of the Fiction peninsula. The family occupied less than a quarter of its space. In her first days, Arden had found herself easily lost in entire abandoned wings, stripped of furniture and fittings. Swallows nested in the faded walls, flitted through empty corridors. A cold wind moaned through broken windows. Powdered mortar fell from the brickwork at each strong gust, and if one day the house would fall, it would not be a day far distant.

Behind Arden, the woman’s black skirt hem whispered ill-gossip against the bare floorboards. By the bleach on the wood Arden suspected the stairs had worn carpet runners once, such as that found in a Bedouin tent-palace, but such valuable things rarely survived the harsh, damp climates south of Lyonne.

Besides, barony or no barony, a Coastmaster’s salary could not afford to deck even a quarter of a country estate out in the manner of its Northern equivalents. The house rested on a precipice of decay, the way a family mausoleum will crumble after the last casket is interred. The men in each candle-smoked portrait lining the walls had all long since passed on. Any other images were daguerreotypes and tinplate prints, things one could obtain with half an hour of a photographer’s time.

Strangely, no women’s faces had been seen fit to add to the cheerless décor. The Justinian line seemed to have sprung like gods, each generation from the other’s forehead without need of a woman at all. Going by the profiles she saw as she squinted in the candlelight, the line had grown a little less vital with each passing iteration, until only Mr Justinian was left at the far corner, his photographed face dilute and chinless.

A little like the blood talent that had drained from Fiction itself, Arden thought.

The Dowager did not leave when Arden laid the krakenskin coat out on her small, slender guest bed.

On first arriving at the house twenty-five days previously, Arden had asked the Dowager privately for a room with a lockable door. A request she could not make of the son.

Dowager Justinian had been surprised at Arden’s wishes, for the Coastmaster’s Manse was patrolled by dogs and a quartet of retired soldiers in her employ. She had granted Arden the room with its hard, narrow bed and a window little bigger than a postage stamp, despite it being hardly a fifth of the size of the guest house Mr Justinian had first expectantly offered.

Still, for three nights in a row Arden had heard footsteps on the landing, the sound of the knob being turned until the lock snapped tight in the jamb. Those nights she drew her bedclothes to her chin and clutched hard the small knife of her profession.

The night visitor never tried to defeat the lock. With entry thwarted, the footsteps would only linger for a moment before moving on.

Now in the dim light of the small room, the blue kraken-cross glowed, an entirely different kind of uninvited visitor. A sullen phosphorescence in each mottled spot, unearthly and benthic. The cut came from the head of the beast, where the fabled kraken crucifix graced the cranium of a bull male at full maturity, one of the few places upon that immense, strange body that could be preserved and tanned. Rarely would any one animal produce enough usable leather for half a garment, let alone the panels for a complete coat. Those pieces never even made it to Clay Capital, Lyonne’s largest city. They were sold to foreign princes or corporate scions, displayed in glass cabinets and only worn during coronations or lying-in-states. A strange call had drawn Arden to this coat in the market.

A murdered whore’s garment.

Arden stroked the decorative leather tooling at the jacket’s sleeve. Pretty, but not stamped in deeply enough for permanency. A too-tentative hand had struck the die on these clumsy patterns. A woman’s hand, she guessed, one unused to those sharp instruments that her brothers all their lives had been allowed access to. Probably sewn the leather as well, judging by the tiny, precise stitches that suited a formal dress better than a coat. A woman’s labour in the threads. Places such as Fiction did not tend towards providing their sons a fully rounded education. Despite an innate skill at leather-work, Clay Portside tailors did a roaring trade in repairing breeches that clueless southernmost men could not repair themselves.

‘It’s such a beautiful thing,’ Arden said. ‘I can’t imagine anyone just throwing it away, no matter how it came into their possession.’

‘I can imagine the beast it once was.’ The Dowager’s black mourning-dress hushed against the cold hearthstones as she went to the miserly fireplace, where the embers of the night before still collected under the ash. She agitated them with an iron poker, adjusted the flue so they would have air to last them into the evening.

Arden wondered if she would see one, at least once, and if it would be as magnificent and terrifying as her books, and beautiful as the coat upon her bed. An entire mountain of copper-body, sinuous beneath the ocean, with arms as long as a steam train of twenty carriages, a pupil so large she could stumble through.

The Dowager seemed to have heard an inkling of her thoughts and said, ‘By the time any specimen makes it into town, it is already cut up for processing. And thank goodness for that. They are hideous. Such arms and legs. Those cold eyes, such unholy thoughts. I’ve heard they grow large enough to consume a whale, or a bull plesiosaur.’ She shuddered. ‘A plesiosaur can grow as big as two elephants, so you can make your own decision as to exactly how much monster we are speaking of.’

‘You’ve actually seen one, Madame Justinian? Monstrom mare? Or is it mostri marino here?’

The Dowager’s poker thrust hard into the ash and disinterred a still-flaming coal.

‘Monstrom mare,’ she said. ‘Once, when I was a girl in Manhattan, I saw a kraken chick washed up upon an oyster-shell beach. Very immature, just a baby really, but each leg was twenty paces long. The old Emperor Krakens never approached so close to shore, there. It is different in Fiction. The creatures are indigenous to Vigil, and in these waters they breed and die.’

A silence descended upon the small, chill room. Though she was mostly Lyonne by blood, Dowager Justinian hailed from that great country far west of the Summerland Sea, in a small village between two rivers called Manhattan, at the province’s south border. Her mother tongue was Lyonne-Algonquian, that great trader’s language that most spoke with some measure of fluency. However had a Vinlander ended up on this windswept Fiction coast, presiding over an immense family estate with a husband who seemingly, based on his portraits, had never aged?

Breeding and death perhaps. That was always the way.

Arden pushed aside the lace curtain at the small window, where beyond the sad patches of lawn and holly oak trees – stunted by the wind and salt – the patient expanse of Vigil’s shallow bay lurked. Giants lived in that place, creatures that had endured the aeons that had made extinct their ancestors. Every dream or terror that existed in a sailor’s lonely night moved and surfaced in those waters. Here be dragons.