Полная версия

The British Are Coming

Germain found broad agreement in the government on Britain’s strategic objective—to restore the rebellious colonies to their previous imperial subservience—but disagreement on how best to achieve that goal. How to defeat an enemy that lacked a conventional center of gravity, like a capital city, and relied on armed civilians who were said to be “deep into principles”? Should British forces hunt down and destroy rebel forces in the thirteen colonies and Canada? Strangle the colonies with a naval blockade? Divide and conquer by isolating either New England or the southern colonies? Hold New York City while subduing the affluent middle colonies between Virginia and New Jersey?

Lord North and some others in the cabinet now inclined toward a land rather than a naval war in hopes that it would be quicker, cheaper, and less provocative to the French. Such a strategy would also give greater succor to American loyalists, whom most British officials, Germain among them, still believed constituted a colonial majority. Yet doubts persisted. “The Americans may be reduced by the fleet,” Secretary at War Barrington had written North, “but never can be by the army.” A War Office report warned that fewer than ten thousand regulars in the British Isles could be spared for overseas duty. Given the booming economy, no more than six thousand more were likely to be recruited in time for the 1776 campaign. “Unless it rains men in red coats,” a British official wrote, “I know not where we are to get all we shall want.” Seventeen recruiting parties in Ireland were enlisting only one or two dozen men per week, combined. “This will never do,” wrote General Harvey, the adjutant general. “We are dribletting away the army, & to no purpose.”

Germain soon encountered other aggravations. Army recruiters competed with the Royal Navy and the East India Company for men. A dozen departments administered the army and overseas military logistics, with fitful coordination, when not outright rivalry, among them. Shipwrights resisting new efficiency rules had gone on strike, bringing Portsmouth and most other yards to a standstill; almost 130 were fired, hampering ship construction and repair. Too often the king and his men were forced to make crucial decisions in the dark, or at least the dusk. Voyages from England to America usually took ten weeks, though sometimes fifteen or more; return trips with the prevailing winds typically required six weeks. A minister might wait four months for acknowledgment that his instructions had been received, or he might wait forever: forty packet boats carrying the Royal Mail would be captured or founder in storms during the war. Misunderstanding, misinformation, and untimely orders were inevitable, particularly when London relied on such flawed sources of intelligence as loyalists desperate for Crown support and royal governors banished from their own capitals. “America,” General Harvey said, “is an ugly job.”

Like the man he called “the mildest and best of kings,” Germain often invoked the need for “zeal.” Sensing that the Americans had advantages of time and space, he vowed to bring “the utmost force of this kingdom to finish the rebellion in one campaign” before other European powers could intervene to aid the rebels. If the insurrection was to be crushed in 1776, half measures would never do.

Zeal could be found in the Prohibitory Act, introduced in the Commons by North on November 20. All vessels found trading with the Americans “shall be forfeited to His Majesty, as if the same were the ships and effects of open enemies.” Cargoes taken on the high seas would be considered lawful seizures. Captured American mariners could be pressed into the Royal Navy. American ports were to be blockaded. The act amounted to “a declaration of perpetual war,” one British politician observed, although John Adams would call it an “act of independency” that galvanized American resistance. Parliament overwhelmingly approved the measure, and the king gave his assent on December 22. The king also had approved the Admiralty’s plan to recall Admiral Graves in hopes that his replacement, Vice Admiral Molyneux Shuldham, a former governor of Newfoundland, would put a spark into the North American squadron.

As for fighting the rebels on land, Germain relied heavily on General Howe’s assessment. An unconventional enemy required original tactics, and Howe’s experience with light infantry and irregular warfare—fighting from “trees, walls, or hedges”—seemed apposite. The commanding general favored squeezing New England between the blockaded ports and the North River, also known as the Hudson, with an offensive launched into New York from Canada once the American interlopers were expelled from Quebec. Germain agreed: a robust fleet must be dispatched to the St. Lawrence, and another to Boston or New York. He immediately pressed the Admiralty to find sufficient ships not only in Britain, but also in Germany and Holland. More combat troops must also be found, from Scotland, Ireland, and the little German principalities.

Germain also knew that for the past two months, the king had been intimately involved in planning another expedition—to the southern colonies, where Scottish émigrés in North Carolina were “said to be well inclined” to the Crown. Within three days of taking office, Germain had adopted this adventure as his own. On the king’s command, seven infantry regiments were to embark in Cork on December 1, with orders “to assist in the suppression of the rebellion.” By late November, His Majesty was informed that Howe and the southern governors had been given authority to raise loyalist troops who would receive British arms and be paid as much as regulars. A commodore, the capable Sir Peter Parker, would escort the expedition to the southern colonies with nine warships and fifteen hundred crewmen. The Admiralty ordered Hawke to Cape Fear on the North Carolina coast to recruit local pilots—with press warrants, if necessary—and to scout for landing sites.

All this was to be “a profound secret,” although, as usual, American agents in London learned of the plan immediately. An assault on the southern colonies would hardly come as a surprise. A recent proposal in the Commons—rejected for the moment—called for sending British regiments to foment slave uprisings, and Governor Dunmore in Virginia had declared that “it is my fixed purpose to arm all my own Negroes and receive all others that will come to me whom I shall declare free.”

Zeal, indeed, would be a hallmark of George Germain’s ministry. More aggressive than his generals, he intended to send them even more reinforcements than they had requested. Howe, facing a grim winter in Boston, praised “the decisive and masterly strokes … effected since your lordship has assumed the conduct of this war.” The American secretary’s moxie was so striking that even the opposition Evening Post predicted he would rise still further in his remarkable rebound to eventually become prime minister. The king was said to be pleased.

Yet amid the green baize desks and the exquisite wall maps in Whitehall, certain truths about the American war remained elusive. Neither Germain nor anyone else in government had carefully analyzed whether Britain’s troop transports, storeships, men-of-war, and other maritime resources could support an ambitious campaign that now included ancillary assaults in the far south and the far north. Little coordination was imposed on one commander in chief in Canada or another in Boston, or with their naval counterparts. Subordinate generals were permitted, even encouraged, to offer their views directly to policy makers in London. Swayed by loyalist exiles and vindictive Crown officials in the colonies, king and cabinet continued to overestimate the breadth and depth of loyal support. No coherent plan obtained to woo the tens of thousands who straddled the fence in America, or to protect those who rejected insurrection but risked severe retaliation from the rebels.

Finally, Germain, like the best of kings he served, could neither grasp the coherence and appeal of revolutionary ideals, nor comprehend the historical headwinds against which Britain now tacked. The American secretary’s lack of “genius sufficient for works of mere imagination” had been acknowledged ironically; that irony would haunt the rest of his days. For now, in a private letter to Howe, he praised the “cordiality & harmony which subsists between you, Clinton, & Burgoyne.” He added:

We want some good news to encourage us to go with the immense expense attending this war.… The providing [of] armies at such a distance is a most difficult undertaking. I do the best I can, and then we must trust to Providence for success.

7.

They Fought, Bled, and Died Like Englishmen

NORFOLK, VIRGINIA, DECEMBER 1775

John Murray, the fourth Earl of Dunmore and the royal governor of Virginia, had few rivals as the most detested British official in North America. Now forty-five, he was a short, pugnacious Scot whose father had been arrested for treason in the 1745 Jacobite rising. Young John subsequently chose to serve the English Crown as a soldier and was permitted to inherit the title after his father’s death in 1756. His estates in Perthshire provided £3,000 annually, but the fourth earl had accumulated both eleven children and expensive tastes. He hired the eminent artist Joshua Reynolds to paint his portrait, in tam-o’-shanter and highland tartans; he also built a summer house with an enormous stone cupola shaped like a pineapple, later derided as “the most bizarre building in Scotland.” Finding himself in financial straits, Dunmore sought to enlarge his fortune abroad. Appointed governor of New York in 1770, he had no sooner arrived than London reassigned him to Virginia, a disappointment that sent him stumbling through Manhattan streets in a drunken rage, roaring, “Damn Virginia … I’d asked for New York.” One loyalist reflected, “Was there ever such a blockhead?”

Virginians later caricatured Dunmore as an inebriated, arrogant philanderer, but he brought to Williamsburg one of America’s largest libraries, an art collection, and assorted musical instruments as evidence of his refinement. He also brought an unquenchable appetite for land, claiming vast tracts between Lake Champlain and what would become Indiana. His popularity surged briefly in 1774 after he launched a punitive military expedition against Shawnee Indians inconvenient to white Virginians who also coveted western acreage. But revolutionary upheaval soon unhorsed him.

Ever since John Rolfe, husband of a young Indian woman named Pocahontas—renamed Rebecca after her conversion to Christianity—learned to cure native tobacco in the early seventeenth century, the crop had dominated Virginia’s economy. The thirty-five thousand tons exported annually from the colony by the early 1770s had brought wealth but also more than £1 million in debt, nearly equal to that of the other colonies combined and often incurred by Tidewater planters living beyond their means. Agents for Glasgow and London merchant houses now controlled most of the tobacco yield. Resentment against British imperial constrictions combined with other colonial grievances, and was compounded by anxiety over the loss of local autonomy. Rebel leaders persuaded Virginians that rebellion “would enhance their opportunities and status,” the historian Alan Taylor later wrote, while also safeguarding political liberties threatened by an overbearing mother country. Planter aristocrats—like the Washingtons, Lees, and Randolphs—helped lead the uprising, but only by common consent. Moreover, evangelical churches, notably the Baptists and Methodists, were promised elevated standing “by disestablishing the elitist Anglican Church” favored by Crown loyalists.

When, in May 1774, Dunmore dissolved the fractious Virginia assembly, the House of Burgesses, delegates simply moved down the street from the capitol to reconvene in the Apollo Room of the Raleigh Tavern, subsequently forming the Virginia Convention to oversee colonial affairs. Anger deepened; resistance grew general. The colony became a leader in boycotting British goods and in summoning the Continental Congress to Philadelphia. Courts closed. Militia companies drilled. The Virginia Gazette published the names of loyalists considered hostile to liberty; some were ordered into western exile or to face the confiscation of their estates. “Lower-class men who did not own property saw the break from Britain as a chance to gain land and become slaveholders,” the historian Michael Kranish would write.

Baffled by Virginians’ “blind and unreasoning fury,” Dunmore brooded in his palace. He peppered London with complaints and with unreliable appraisals of colonial politics, receiving little guidance in return. In April 1775, even before learning of events in Lexington and Concord, he ordered a marine detachment to confiscate gunpowder from the public magazine in Williamsburg on grounds that “the Negroes might have seized upon it.” Rebel drums beat and militia “shirtmen”—so named for their distinctive hunting garb—threatened “to seize upon or massacre me,” he told Whitehall. After reimbursing the rebels £330 for the powder he had impounded, in early June he fled with his family in the dark of night for refuge first aboard the Magdalen, then on the Fowey, and eventually on the Eilbeck, an unrigged merchant tub he renamed for himself. With his wife and children dispatched to Britain, Dunmore’s dominion was reduced to a gaggle of loyalist merchants, clerks, and scrofulous sailors. Still, with just a few hundred more troops, he wrote London in August, “I could reduce the colony to submission.”

The Gazette would accuse him of “crimes that would even have disgraced the noted pirate Blackbeard.” Most of his felonies involved what were derided as “chicken-stealing expeditions” against coastal plantations, although he also impounded a Norfolk printing press from a seditious publisher who dared suggest that Catholic blood ran through Dunmore’s veins.

But then the earl decided to become an emancipator.

Roughly five hundred thousand Americans were black, some 20 percent of the population, and nine in ten of those blacks were slaves. In southern colonies, the proportion of blacks to whites was much higher: 40 percent of Virginia’s half million people were of African descent—often from cultures with military traditions—and white fear of slave revolts was a prominent reason for keeping colonial militias in fighting trim. Many white masters were reluctant to allow missionaries to convert their chattel for fear that radical Christian notions would make them even less docile. Political turmoil in America gave some slaves hope, and for months runaway blacks had sought protection from the regulars in a belief that British views on slavery differed markedly from those of southern planters.

In truth, although slavery had begun to disappear in England and Wales, Britain’s colonial economy was built on a scaffold of bondage. Among many examples, the almost two hundred thousand slaves in Jamaica outnumbered whites fifteen to one, and an uprising in 1760 had been suppressed by shooting several hundred blacks. The slave trade, carried largely in British ships, had never been more prosperous than in the years just before the American rebellion, and Britain would remain the world’s foremost slave-trading nation into the nineteenth century.

Dunmore’s initial muttering to London in the early summer about emancipation was largely a bluff. He recognized that bound labor was critical to the white commonwealth he governed. The king’s government was unenthusiastic about wrecking colonial economies or encouraging slave revolts that might infect the West Indies. But by mid-fall Dunmore was desperate to regain the initiative in Virginia. Reinforced with a few dozen 14th Foot soldiers who’d arrived from St. Augustine, he launched several aggressive Tidewater raids, capturing or destroying seventy-seven rebel guns “without the smallest opposition,” as a British captain wrote General Howe on November 1, “which is proof that it would not require a very large force to subdue this colony.” Raising the king’s standard—unable to find British national colors, Dunmore settled for a regimental banner—he administered loyalty oaths to those who pinned on strips of red cloth as a badge of “true allegiance to his sacred Majesty George III.” The price of red fabric rose in Norfolk stores, reflecting demand.

On November 7, using his confiscated printing press, Dunmore declared martial law and issued a proclamation: “I do hereby further declare all indented servants, Negroes, or others (appertaining to rebels) free, that are able and willing to bear arms, they joining His Majesty’s troops as soon as may be.” Liberation applied only to the able-bodied slaves of his foes. There would be no deliverance for his own fifty-seven slaves—abandoned in Williamsburg when he fled and for whom he would claim compensation from the government—nor would loyalists’ chattel be freed. The governor intended to crush a rebellion, not reconfigure the social order.

Still, eager blacks found their way into his ranks. Fitted by the British with linen or sail-canvas shirts, often with the motto “LIBERTY TO SLAVES” across their chests, runaways with names like Sampson, Pompey, and Glasgow were formed into an “Ethiopian Regiment,” under white officers. Maryland patriots tried to bar correspondence with Virginia in a futile effort to prevent news of Dunmore’s gambit from spreading north. A Philadelphian wrote, “The flame runs like wild fire through the slaves.” British sailors in cutters raided riverside plantations in “Negro-catching” forays. On November 14, Dunmore personally led a detachment of Ethiopians, regulars, marines, and twenty Scottish clerks in a rout of Virginia shirtmen at Kemp’s Landing, southeast of Norfolk. The Americans loosed a volley or two before fleeing, their leaders reportedly “whipping up their horses” except for those too drunk to ride.

The small victory was good for recruiting both white loyalists—Dunmore boasted that three thousand men had joined him—and black runaways, who, he reported, “are flocking in.” The governor triumphantly marched into Norfolk on November 23. Many Tidewater loyalists publicly revealed their sympathies, and some avowed patriots retreated to the safer ground of neutrality. “This pink-cheeked time-server,” as the historian Simon Schama called Dunmore, “had become the patriarch of a great black exodus.” Thomas Jefferson would later claim that from Virginia alone tens of thousands of slaves escaped servitude during the war, a number likely inflated but suggestive of white anxiety.

“With our little corps I think we have done wonders,” Dunmore wrote Howe on November 30. “Had I but a few more men here, I would immediately march to Williamsburg … by which I should soon compel the whole colony to submit.” Norfolk possessed a fine harbor that “could supply your army and navy with every necessary of life,” if properly protected. His senior naval officer added in a dispatch from the Otter on December 2 that the Americans, “from their being such cowards and cold weather coming on,” were expected to remain quiet through the winter.

That was unlikely. Dunmore had miscalculated: rather than cowing white southerners and pressuring slave owners to remain loyal, he would unify Virginians as never before. An American letter written on December 6 and subsequently published in a London newspaper captured the prevailing sentiment: “Hell itself could not have vomited anything more black than his design of emancipating our slaves.”

The proclamation backfired throughout the South, even though many runaways from Georgia to Mount Vernon eventually made their way to coastal waters wherever British men-of-war appeared. Rumors spread that slaves who murdered their masters would be entitled to their estates. The lawyer Patrick Henry, whose recent demand “Give me liberty or give me death” clearly did not countenance “black banditti,” circulated copies of Dunmore’s announcement in order to inflame white slave owners. For many, a war about political rights now became an existential struggle to prevent the social fabric from unraveling. Even Piedmont yeomen whose slave holdings were limited to renting a field hand or two took offense. Edward Rutledge, a prominent South Carolina politician, wrote in December that arming freed slaves tended “more effectually to work an eternal separation between Great Britain and the colonies than any other expedient which could possibly have been thought of.”

The Virginia Gazette urged slaves to “obey your masters … and expect a better condition in the next world.” Another, more sinister article warned, “Whether we suffer or not, if you desert us, you most certainly will.” A British official in Annapolis wrote, “This measure of emancipating the Negroes has excited a universal ferment, and will, I apprehend, greatly strengthen the general confederacy.” “Devil Dunmore” was vilified as “that ignoramus Negro-thief.” Had the British “searched through the world for a person the best fitted to ruin their cause,” wrote Richard Henry Lee, “they could not have found a more complete agent than Lord Dunmore.”

No slave master was more incensed than General Washington. “That arch traitor to the rights of humanity, Lord Dunmore, should be instantly crushed, if it takes the force of the whole colony to do it,” he wrote. In another outburst from Cambridge, Washington told Lee, “Nothing less than depriving him of life or liberty will secure peace in Virginia.” Otherwise, the governor “will become the most formidable enemy America has.”

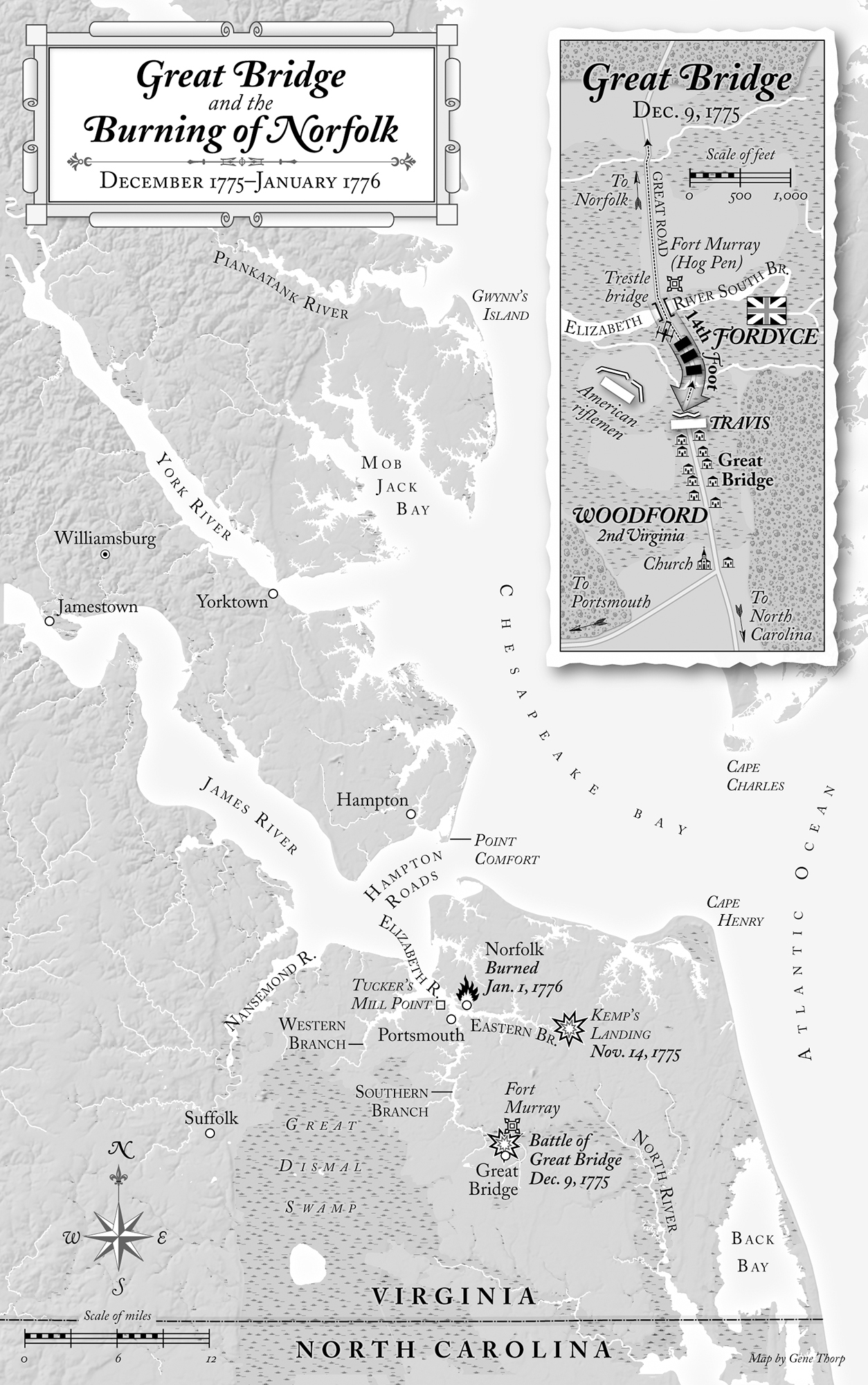

A chance to confront the “Negro-thief” soon occurred twelve miles south of Norfolk at Great Bridge, on the rutted road from Carolina. Here two-wheeled carts brought cypress shingles and barreled turpentine from the Great Dismal Swamp, and drovers guided their flocks and herds to Tidewater slaughterhouses. A hamlet of twenty structures dominated by a church stood near the south branch of the Elizabeth River, which was spanned by a trestle bridge forty yards long and approached by long plank causeways through the marshlands. “Nine-tenths of the people are Tories,” one Virginian reported, “who are the poorest, miserable wretches I ever saw.” Just north of this settlement, Dunmore, exhbiting what a later commentator called “his characteristic unwisdom,” had built an earthen fort with two 4-pounders to command the bridge and a wooden stockade to house a garrison of a hundred regulars and Ethiopians. He named the fort for himself, but rebel shirtmen called it the Hog Pen.

By Friday, December 8, more than seven hundred militiamen had gathered a quarter mile south of the Hog Pen. A zigzag breastwork, seven feet high with fire steps and gun loopholes, served as their redoubt. Their numbers included the 2nd Virginia Regiment, commanded by Colonel William Woodford, a French and Indian War veteran. A Culpeper minute company carried a flag displaying a coiled rattlesnake and the motto “DON’T TREAD ON ME”; in their ranks marched a rangy, twenty-year-old lieutenant named John Marshall, who one day would be chief justice of the Supreme Court. The western riflemen typically wore deerskin trousers and leaf-dyed hunting shirts, with a buck’s tail affixed to the hat and a scalping knife sheathed on the belt. Many had “liberty or death” printed in large white script over their hearts, although one young rifleman admitted to preferring “liberty or wounded.”

Skirmishers and raiding parties from both sides had exchanged potshots for a week, burning isolated houses to discourage snipers. Some rebel officers wanted to execute captured slaves but agreed to leave their fate to the convention in Williamsburg. Dunmore, who remained aboard his floating headquarters near Norfolk, may have been duped by an American deserter who claimed that the rebels had fewer than three hundred men; he may also have learned, correctly, that more rebels were en route from Williamsburg and North Carolina. The governor dispatched additional regulars to Great Bridge, along with British sailors and loyalist volunteers, bringing the force there to perhaps four hundred. With more impetuous unwisdom, he also ordered the garrison to leave the secure fort and attack the American fortifications before they could be reinforced.