Полная версия

The British Are Coming

5.

I Shall Try to Retard the Evil Hour

INTO CANADA, OCTOBER–NOVEMBER 1775

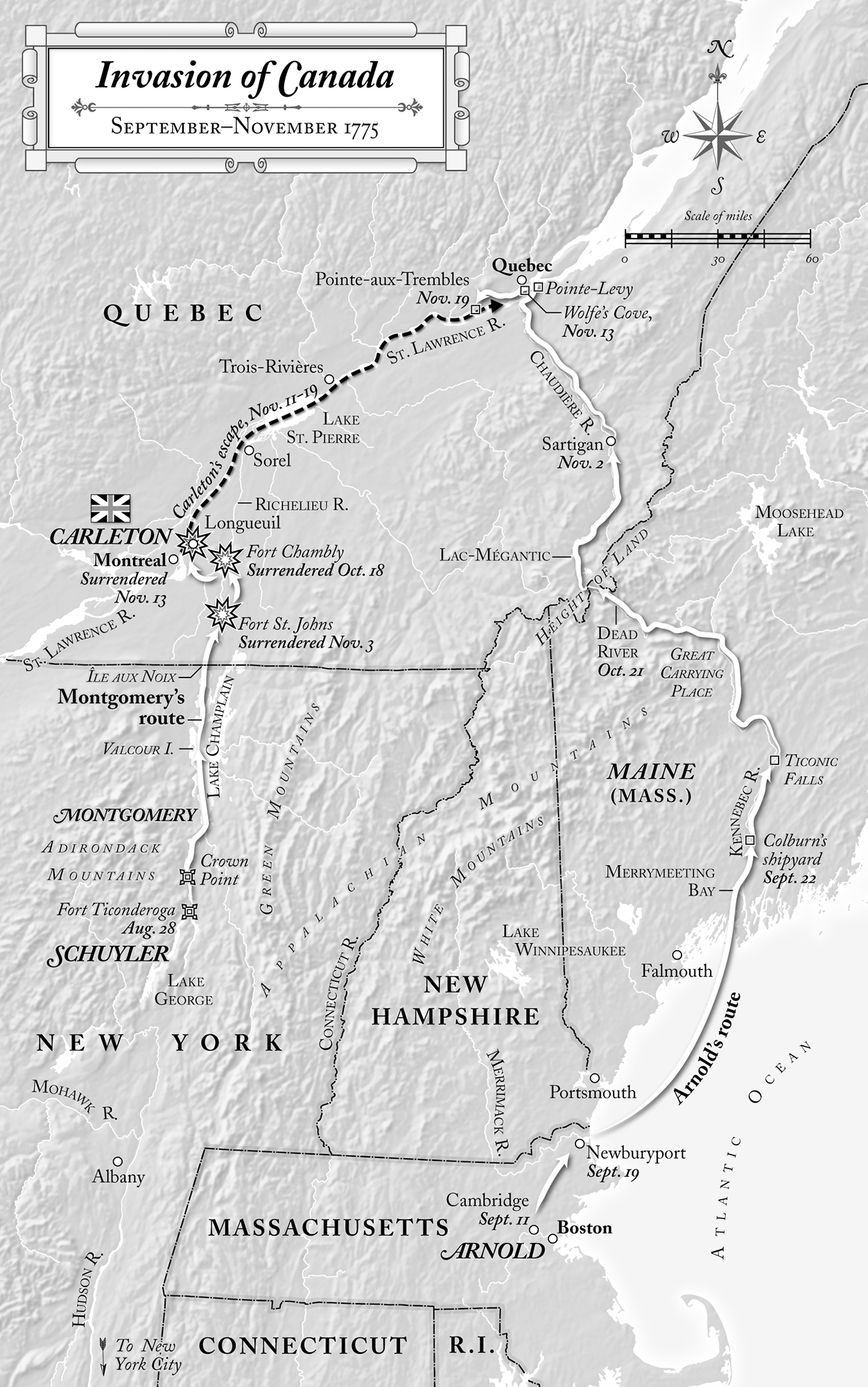

Some 230 miles northwest of Boston, a second siege now threatened Britain’s hold on Canada. For almost a month, more than a thousand American troops had surrounded Fort St. Johns, a dank compound twenty miles below Montreal on the swampy western bank of the Richelieu River in what one regular called “the most unhealthy spot in inhabited Canada.” A stockade and a dry moat lined with sharpened stakes enclosed a pair of earthen redoubts, two hundred yards apart and connected by a muddy trench. A small stone barracks, a bakery, a powder magazine, and several log buildings chinked with moss stood in the southern redoubt. Thirty cannons crowned the ramparts and poked through sodded embrasures, spitting iron balls whenever the rebels approached or grew too impertinent with their own artillery. By mid-October, seven hundred people were trapped at St. Johns, among them most of the British troops in Canada—drawn from the 26th Foot and the 7th Foot, known as the Royal Fusiliers—as well as most of the Royal Artillery’s gunners, eighty women and children, and more than seventy Canadian volunteers. Sentries cried, “Shot!” whenever they spotted smoke and flame from a rebel battery, and hundreds fell on their faces in the mud as the ball whizzed overhead or splatted home, somewhere.

The regulars still wore summer uniforms and suffered from the cold: the first hard frost had set on September 30, followed by eight consecutive days of rain. Some ripped the skirts from their coats to wrap around their feet. The garrison now lived on half-rations and shared a total of twenty blankets, with no bedding or straw for warmth. Only a shallow house cellar in the northern redoubt offered any shelter belowground, and it was crammed with the sick and the groaning wounded. Major Charles Preston, the fort’s dimple-chinned commandant, had sent four couriers to plead for help in Montreal. Each slipped from the fort at night and scuttled through the dense Richelieu thickets. But no reply had been heard—“not a syllable,” as Preston archly noted—since an order had arrived from the high command in early September to “defend St. Johns to the last extremity.”

At one p.m. on Saturday, October 14, many cries of “Shot!” were heard when the rebels opened a new battery with two 12-pounders and two 4-pounders barely three hundred yards away on the river’s eastern shore. One cannonball ricocheted from a chimney, demolishing the house and killing a lieutenant; another detonated a barrel of gunpowder in an orange fireball, killing another man and wounding three. Balls battered the fort’s gate and clipped its parapet. A 13-inch shell from a rebel mortar called Old Sow punched through the barracks roof, blowing out windows while killing two more and wounding five. “The hottest fire this day that hath been done here,” an officer told his diary.

The next day was just as hot: 140 rebel rounds bombarded the fort on Sunday, perforating buildings and men. A Canadian cook lost both legs. A twelve-gun British schooner, the Royal Savage, was moored between the redoubts along the western riverbank, although the crew fled to the fort after complaining that it was “impossible to sleep on board without being amphibious.” Rebel gunners now took aim at Royal Savage with heated balls, punching nine holes in the hull and three through the mainmast, then demolishing the sternpost holding the rudder. “The schooner sunk up to her ports … and her colors which lay in the hold were scorched,” a British lieutenant, John André, wrote in his journal. She soon sank with a gurgle into the Richelieu mud.

Major Preston and most of his men remained defiant, despite the paltry daily ration of roots and salt pork, despite the awful smells seeping from the cellar hospital, despite the rebel riflemen who crept close at dusk for a shot at anyone careless enough to show his silhouette on the rampart. British ammunition stocks dwindled, but gunners still sought out rebel batteries, smashing the hemlocks and the balm of Gilead trees around the American positions north and west of the fort. Yet without prompt relief—whether from Montreal, London, or heaven—few doubted that the last extremity had drawn near. “I am still alive,” wrote one of the besieged in late October, “but the will to live diminishes within me.”

For nearly a century, Americans had seen Canada as a blood enemy. New Englanders and New Yorkers especially never forgave the atrocities committed by French raiders and their Indian confederates at Deerfield, Schenectady, Fort William Henry, and other frontier settlements. Catholic Quebec was seen as a citadel of popery and tyranny. The French, as a Rhode Island pastor proclaimed in 1759, were children of the “scarlet whore, the mother of harlots.”

Britain’s triumph in the Seven Years’ War and its acquisition of New France in 1763—known in Quebec as “the Conquest”—gladdened American hearts. Many French Canadians decamped for France. Priests lost the right to collect tithes and the benefit of an established state religion. A small commercial class of English merchants, friendly to American traders, took root. The Canadian population—under a hundred thousand, less than New Jersey—was still largely rural, illiterate, dependent on farming and fur, and essentially feudal. Most were French-Canadian habitants, or peasants, now known as “new subjects,” since their allegiance to the British Crown was barely a decade old and deeply suspect. Many secretly hoped that France would win back what had been lost or that the “Londoners”—Englishmen—would tire of the weather and go home. Largely descended from Norman colonists sent to the New World by Louis XIV, the habitants were described by an eighteenth-century author as “loud, boastful, mendacious, obliging, civil, and honest.” A few thousand “old subjects”—Anglo merchants and Crown officials—congregated in Montreal and Quebec City. Nova Scotia and the maritime precincts remained wild, isolated, and sparsely peopled.

As tensions with Britain escalated, many Americans—Benjamin Franklin and Samuel Adams among them—considered Canada a natural component of a united North America. The First Continental Congress in October 1774 sent Canadians an open letter, at once beckoning and sinister: “You have been conquered into liberty.… You are a small people, compared to those who with open arms invite you into fellowship.” Canadians faced a choice between having “all the rest of North America your unalterable friends, or your inveterate enemies.”

The Quebec Act, which took effect in May 1775, infuriated the Americans and altered the political calculus. Canada would be ruled not by an elected assembly, but by a royal governor and his council, a harbinger, in American eyes, of British tyranny across the continent. Even more provocative were the provisions extending Quebec’s boundaries south and west, into the rich lands beyond the Appalachians for which American colonists had fought both Indians and the French, and the recognition of the Roman Catholic Church’s status in Canada, including the right of Catholics to hold office and citizenship, to again levy parish tithes, to serve in the army, and to retain French civil law. These provisions riled American expansionists—fifty thousand of whom now lived west of the mountains—and revived fears of what one chaplain described as “this vast extended country, which has been for ages the dwelling of Satan.” Catholic hordes—likened to a mythical beast found in the Book of Revelation, “drunk with the wine of her fornications”—could well descend on Protestant America. It was said that hundreds of pairs of snowshoes had been readied, should Canadian legions be commanded to march southward.

War in Massachusetts, and the American capture of Ticonderoga and Crown Point, brought matters to a head. Congress dithered, initially proposing to return the two forts rather than end any chance of reconciliation with Britain; then decided to keep them; then dithered some more over whether to preemptively attack Quebec when it became clear that Canada was unlikely to send delegates to Philadelphia despite an invitation to “the oppressed inhabitants” to make common cause as “fellow sufferers.” The debate raged for weeks. Even Washington, who had qualms about opening another front, saw utility in capturing Canadian staging grounds before the reinforced British could descend on New York and New England. Others saw a chance to seize the Canadian granary and fur trade, to forestall attacks by Britain’s potential Indian allies, and to preclude the need to rebuild Ticonderoga and other frontier defenses. Britain reportedly had fewer than seven hundred regulars scattered across Quebec; two of the four regiments posted there had been sent to Boston in 1774 at Gage’s request. Canada conceivably could be captured and converted into the fourteenth American province with fewer than two thousand troops in a quick, cheap campaign. Skeptics argued that an invasion would convert Americans into aggressors, disperse scarce military resources, and alienate both American moderates and British supporters of the colonial cause. Some recalled that during the last war, more than a million British colonists and regulars had needed six years, several of them disastrous, to subdue less than seventy thousand Canadians and their French allies.

In late June, Congress finally ordered Major General Philip Schuyler, a well-born New Yorker, to launch preemptive attacks to prevent Britain from seizing Lake Champlain. He was authorized to “take possession of St. Johns, Montreal, and any other parts of the country” if “practicable” and if the intrusion “will not be disagreeable to the Canadians.” Under the guise of promoting continental “peace and security”—Congress promised to “adopt them into our union as a sister colony”—Canada was to be obliterated as a military and political threat. Most Canadians were expected to welcome the incursion, a fantasy not unlike that harbored by Britain about the Americans. This would be the first, but hardly the last, American invasion of another land under the pretext of bettering life for the invaded.

Congress had denounced Catholics for “impiety, bigotry, persecution, murder, and rebellion through every part of the world.” Now it found “the Protestant and Catholic colonies to be strongly linked” by their common antipathy to British oppression. In a gesture of tolerance and perhaps to forestall charges of hypocrisy, Congress also acknowledged that Catholics deserved “liberty of conscience.” If nothing else, the Canadian gambit caused Americans to contemplate the practical merits of inclusion, moderation, and religious freedom. The Northern Army, as the invasion host was named, was to be a liberating force, not a vengeful one.

For two months little had gone right in the campaign. The Northern Army comprised twelve hundred ill-trained, ill-equipped, insubordinate troops, many without decent firelocks or gunsmiths at hand to fix them. When General Schuyler reached Ticonderoga at ten p.m. on a July evening, the lone sentinel tried unsuccessfully to waken the watch and the rest of the garrison. “With a penknife only,” Schuyler wrote Washington, “I could … have set fire to the blockhouse, destroyed the stores, and starved the people here.” Three weeks later, having advanced not a step farther north, he reported that he had less than a ton of gunpowder, no carriages to move his field guns, and little food. His men, scattered along the Hudson valley, seemed “much inclined to a seditious and mutinous temper.” Carpenters building flat-bottomed bateaux to cross Lake Champlain lacked timber, nails, pitch, and cordage. When Schuyler requested reinforcements, the New York Committee of Safety told him, “Our troops can be of no service to you. They have no arms, clothes, blankets, or ammunition; the officers no commissions; our treasury no money.”

Tall, thin, and florid, with kinky hair and a raspy voice, Philip Schuyler was among America’s wealthiest and most accomplished men. The scion of émigré Dutch land barons, he owned twenty thousand acres from New York to Detroit, including a brick mansion on a ridge above Albany with a view of the Catskills and hand-painted wallpaper depicting romantic Roman ruins. His country seat on Fish Creek in Saratoga abutted sawmills and a flax plantation that spun linen. He spoke French and Mohawk, understood lumber markets, mathematics, boat-building, slave owning, navigation, hemp cultivation, and, from service in the last war, military logistics. British officers had praised his “zeal, punctuality, and strict honesty.” The body of his young friend Lord George Howe, slain by the French at Ticonderoga, lay in the Schuyler family vault for years before permanent burial in a lead casket beneath St. Peter’s chancel in Albany. As a delegate to Congress, Schuyler sat with Washington on a committee to collect ammunition and war matériel, then rode north with him from Philadelphia after both received their general’s commissions. Among other services rendered the Northern Army, Schuyler helped persuade Iroquois warriors to renounce their traditional allegiance to Britain and to remain neutral, at least for now, in what he described—during pipe-smoking negotiations at Cartwright’s Tavern in Albany—as “a family quarrel.” To impress the Indians with American strength, he had ordered troops to march in circles through the town, magnifying their numbers.

For all his virtues, Schuyler was wholly unfit to command a field army in the wilderness. His urbane, patrician mien could seem “haughty and overbearing,” as one chaplain wrote, especially to New Englanders who habitually disliked the New York Dutch because of border disputes and ethnic frictions. Almost from the start of the campaign, the general was accused of being a secret Tory and of sabotaging the Canadian expedition. Not yet forty-two, he also suffered from “a barbarous complication of disorders,” including gout, malaria, and rheumatic afflictions. His clinical bulletins to Washington routinely described “a very severe fit of the ague,” or “a copious scorbutic eruption,” or “a copious discharge from an internal impostume in my breast.” He was not a well man.

Alarming reports in late August of British vessels at St. Johns preparing to sortie onto Lake Champlain forced the Americans into motion. Brigadier General Richard Montgomery set out from Ticonderoga on August 31 with the twelve hundred men and four 12-pounders aboard a schooner, a sloop, and a mismatched flotilla of bateaux, row galleys, and canoes. He urged the ailing Schuyler, his superior, to “follow us in a whaleboat.… It will give the men great confidence in your spirit and activity.” Despite the “inflexible severity of my disorders,” Schuyler subsequently headed north in early September with a stack of proclamations in French to be scattered across Quebec: “We cannot doubt that you are pleased that the Grand Congress have ordered an army into Canada.” From Cambridge, Washington wrote, “I trust you will have a feeble enemy to contend with and a whole province on your side.”

Wishing did not make it so. Reunited on the upper reaches of Lake Champlain, Schuyler and Montgomery led their men down the Richelieu, which flowed north from the lake for almost eighty miles to the St. Lawrence River. The invaders disembarked on September 6 just short of Fort St. Johns, about a third of the distance to the St. Lawrence, then struggled toward the compound in “a tangled way” for a quarter mile through a swampy woodland, only to be ambushed by Indians and regulars in a confused melee that left nine Americans dead and as many wounded.

For more than a week, the invasion stalled. Priests in Montreal celebrated Canada’s deliverance in a thanksgiving mass with a jubilant Te Deum. Another American advance on the fort turned to fiasco when strange noises spooked the men, who “ran like sheep,” in Montgomery’s contemptuous phrase. With difficulty and a threat of bayonets, they were restrained from pushing off in the boats and abandoning their officers on the shoreline. “Such a set of pusillanimous wretches never were collected,” Montgomery wrote his wife. “Could I, with decency, leave the army in its present situation, I would not serve an hour longer.”

If Montgomery could not abandon the Northern Army, Schuyler could and did. Crippled by rheumatic and perhaps malarial miseries, he reported to Philadelphia that “I am now so low as not to be able to hold the pen.” On September 16, soldiers hoisted him into a covered boat and rowed him in the rain back to a Ticonderoga sickbed. “If Job had been a general in my situation,” he wrote Congress, “his memory had not been so famous for patience.”

Further misfortune befell the invaders when Ethan Allen, the conqueror of Ticonderoga, foolishly decided to storm Montreal with a small band of henchmen rather than enlist Canadian recruits in the countryside, as he had been instructed. Described by one acquaintance as “a singular compound of local barbarisms, scriptural phrases, and oriental wildness,” Allen hoped for the glory of a quick victory. But as he approached the city, several dozen regulars and two hundred French and English militiamen sortied through the gates on September 25 to catch him by surprise along the St. Lawrence. “The last I see of Allen,” one of his men wrote, “he was surrounded, had hold with both hands the muzzle of a gun, swinging it around.” Captured and paraded through Montreal, he would be shipped to England in thirty-pound leg irons and imprisoned in the lower reaches of Pendennis Castle, on the southern coast of Cornwall, a cautionary tale for traitors to the Crown. Allen’s “rash and ill-concerted measure,” an American chaplain told his journal, “not only served to dishearten the Army and weaken it, but it prejudiced the people against us and both made us enemies and lost us friends.” Montgomery added in a dispatch to Schuyler, “I have to lament Mr. Allen’s imprudence and ambition.”

Despite such misfires and misadventures, Montgomery—tall, bald, and Dublin-born—soon had the whip hand at St. Johns. Reinforcements streamed north across Lake Champlain in October, including Connecticut regiments and a New York artillery detachment with siege guns, bringing American strength to 2,700. Gunners built batteries south of the fort and across the Richelieu to the northeast. More than 350 men slipped ten miles down the river to fire a few cannonballs at the high-walled British fort at Chambly. The 84-man garrison promptly surrendered on October 18, handing over 124 barrels of gunpowder, 233 muskets, 6,600 cartridges in copper-hooped barrels, and ample stocks of flour, pork, and marine supplies.

“We have gotten six tons of powder which, with God’s blessing, will finish our business here,” Montgomery wrote Schuyler. No less ominous for St. Johns, a putative rescue force from Montreal—some eight hundred habitants, Indians, loyal merchants, and regulars—assembled on an island in the St. Lawrence on October 30, then beat across the river toward Longueuil in several dozen bateaux. Three hundred Americans rose up along the south bank to scourge the boats with musketry and grapeshot, killing between a few and a few dozen—depending on the account—without a single Yankee casualty. The bateaux scattered, the habitants and loyalists deserted in droves, and St. Johns’ last hope for salvation vanished.

Three hundred yards northwest of the beleaguered fort, yet another American battery had been hacked from the swamp and furnished with cannons, mortars, and a chest-high breastworks. Men lugged iron balls from the Richelieu on their shoulders or in slings made from their trousers, while gunners packed the newly acquired powder into cartridges and explosive shells. At ten a.m. on Wednesday, November 1—All Saints’ Day—the guns opened in concert with the battery across the river in a stupefying bombardment of a thousand balls and more than fifty shells, which by sunset had “knocked everything in the fort to shatters,” an American officer exulted. Montgomery halted the cannonade long enough to send a white flag to the gate, carried by a Canadian prisoner who swore upon the Holy Evangelist that the rescue force from Montreal had indeed been routed, that no more help was forthcoming, and that further resistance would bring “melancholy consequences.”

After a fifty-three-day siege, with sixty defenders killed or wounded, his food and powder all but gone, Major Preston had finally had enough. He stalled for a day by trying to squeeze concessions from the Americans. Would the honors of war be observed? Could officers keep their baggage? Sidearms? Why not permit the men to sail for England on parole? “Let me entreat you, sir, to spare the lives of a brave garrison,” Montgomery told him. The British would be “treated with brotherly affection” in Connecticut jails. Negotiations briefly broke down when the proposed articles of capitulation suggested that British “fortitude and perseverance” should have been “exerted in a better cause.” Preston declared that his men would rather “die with their arms in their hands than submit to the indignity of such a reflection.” Montgomery struck the clause but threatened to resume his bombardment “if you do not surrender this day.”

At eight a.m. on November 3, a wet, blustery Friday, Montgomery’s men shouldered their firelocks in a field south of the fort. A few wore smart uniforms, like the gunners in blue coats with buff facings; more sported drab yeoman togs and slouch hats. To the trill and rap of fife and drum, the defeated garrison marched six abreast with colors flying through the gate, some of them mud-caked, their feet bound in rags. First came the 26th Foot in brick-red coats with pale yellow facings; then the Royal Fusiliers with blue facings; then Royal Artillery troops in dark blue coats and once-white waistcoats, drawing two small guns; and finally sailors in pigtails, Indians in blankets and feathers, a few kilt-clad Scots, carpenters, cooks, servants, and a gaggle of women and fretful children. At least one officer kept a locket portrait of his lover hidden under his tongue in case the Yankees began to pilfer. Major Preston strutted to the front of the American ranks. “The tears run down his cheeks,” a Connecticut soldier reported, “and he cried like a child.” On Preston’s order the troops stacked their muskets—officers kept swords and sidearms—then shuffled into the waiting bateaux for the long journey across Champlain to captivity in New England.

More than three-quarters of the British regulars in Canada had now been captured or killed, along with virtually all of the trained artillerymen. The booty from St. Johns included seventeen fine brass guns, two brass howitzers, twenty-two iron guns, eight hundred stand of small arms, sails, pitch, tar, and precious nails. The cost of the long siege to the American invaders was steep—a hundred combat casualties and another thousand men, including their commanding general, sent back to New York with various ailments. But the front door to Canada had swung open, and thousands of additional Yankees stood ready to march through.

As the last of his captives vanished up the gray Richelieu, Brigadier General Montgomery took a moment to scribble his wife a note. “If I live,” he wrote, “you may depend upon it that I will see you this winter.”

That Richard Montgomery now prepared to finish conquering Canada for the American cause was no small irony, for as a young regular officer in an earlier life he had helped to conquer it for the British Empire. The youngest son of an Irish baronet, he was commissioned as an ensign after two years of college in Dublin, then devoted sixteen years to the king’s service, half of it in North America and the West Indies. Slender and lightly pocked, he blamed “the heat and severity” of combat in Martinique and Cuba in 1762 for the loss of his hair; he blamed a girlfriend for other disorders. “She has clapped me,” he wrote a fellow officer in 1769. “The flames of my passion have subsided with those of my urine.”

An end to the French war meant an end to promotions, and in 1772, after years as a captain—including wartime service at St. Johns and Montreal—Montgomery in disgust sold his commission for £1,500. “I have of late conceived a violent passion,” he wrote a cousin. “I have cast my eyes on America, where my pride and poverty will be much more at their ease.” Packing up his volumes of Hume, Montesquieu, and Franklin’s Experiments, as well as a new microscope, surveying equipment, and draftsman’s tools, he sailed for New York and bought a seventy-acre farm just north of Manhattan. Still only thirty-four, in July 1773 he married well: Janet Livingston was the eldest daughter of a prominent New York patriot judge who owned a thirteen-thousand-acre estate in Albany County. Elected to the New York Provincial Congress when political unrest turned to rebellion, Captain Montgomery abruptly found himself appointed a brigadier general; his “air and manner designated the real soldier,” one subordinate wrote. But the honor only deepened his Irish fatalism. He told a former British comrade of a premonition that he would die “by a pistol,” and before marching north he wrote his will. “I have been dragged from obscurity much against my inclination and not without some struggle,” he told Janet, adding that as soon as he could “slip my neck out of the yoke, I will return to my family and farm.”