Полная версия

Spying on Whales

The metal prongs that Ari assembled looked like an elaborate set of rabbit ears from an old television set. He plugged the antenna into a small receiver with a speaker, and after a few moments, we heard a series of intermittent beeps. “That gap between the beeps tells us that the whale is sleeping, rising up to the surface to breathe, and then sinking back down.” Ari smiled. “Just dozing, belly full of krill. Not a bad way to spend a Saturday night.” We would need to come back later and listen again for our tag until it floated freely, beeping uninterrupted.

Most large baleen whale species alive today belong to the rorqual family, which feed on krill and other small prey by lunging underwater. They comprise the more familiar members of the cetacean bestiary, including humpbacks, blue whales, fin whales, and minke whales. Rorquals are also the most massive species of vertebrates ever to have evolved on the planet—far heavier than the largest dinosaurs. Even the smallest rorquals, minke whales, can weigh ten tons as adults, about twice as much as an adult bull African elephant. Rorquals are easy to distinguish from any other baleen whale, such as a gray whale or a bowhead whale: look for the long, corrugated throat pouch that runs from their chin to their belly button. (And yes, whales have belly buttons, just like you and me.) The features that make rorquals so obviously different from other baleen whales also play a critical role in how they feed.

Across whole ocean basins, individual whales find their food using probability, heading for feeding grounds burned into memory from a lifetime of migration. Rorquals travel routes that span hemispheres over the seasons; an individual whale might migrate from the tropics in the winter in search of mates and to bear young, then to the poles during the summer to forage under constant sunlight. Baleen whales still retain olfactory lobes, unlike their toothed cousins, such as killer whales and dolphins, which have lost them. Baleen whales might smell some aspect of their prey at the water’s surface, and it is possible that this mechanism could refine their search once on the scene. Originally their sense of smell evolved for transmission through air, not water; we know little beyond the basics about this sense in whales. Somehow, whales manage to be in the right place at the right time to feed. And what’s clear from biologging is that once in the right place, baleen whales spot the prey patches from below, probably approaching them by sight. Lacking the echolocation of their toothed relatives, vision is likely the dominant sense for baleen whales at short range.

With prey in range, a rorqual accelerates, fluking at top speed, and begins the amazing process of a lunge. Surging from below, it opens its mouth only seconds before it arrives at a patch of krill or school of fish, which may be as big as or bigger than the entire whale. When it lowers its jaws, the rorqual exposes its mouth immediately to a rush of water that pushes its tongue backward, through the floor of its mouth, into its throat pouch. In mere seconds, the accordion-like grooves of its throat pop out like a parachute. After engulfing the prey-laden water, the whale slows, almost to a halt, pouch distended and looking bloated, nothing like its airfoil-shaped profile from moments prior. Over the next minute, it slowly expels water out of its mouth through a sieve of baleen, until its throat pouch returns to its original form, the prey swallowed. For their part, krill and fish deploy collective defensive behavior by dispersing to try to escape the oncoming maw of death. In the end, a successful whale takes a bite out of a much bigger, more diffuse and dynamic superorganism.

Lunge feeding has been described as one of the largest biomechanical events on the planet, and it’s not hard to imagine why when you consider that an adult blue whale engulfs a volume of water the size of a large living room in a matter of seconds. Tags on humpbacks in other parts of Antarctica show how they sometimes feed close to the seafloor in pairs, swimming alongside each other as they scrape the bottom with their protruding chins in mirrored unison. Tags have also shown us that rorquals are right- or left-handed, just like us, favoring either a dextral or sinistral direction when they roll their bodies to feed.

The more scientists tag whales, the more it’s apparent that there’s still much that we don’t know. It turns out that blue whales have a behavior where they spin 360 degrees underwater in a pirouette before they lunge, probably to line up their mouths precisely with a patch of krill. Other lightweight tags, launched with barbs that cling more deeply beneath the skin on the dorsal fin, have tracked the movement of Antarctic minke whales migrating over eight thousand miles of open ocean, from the Antarctic Peninsula to subtropical waters. These tags upload data directly to satellites whenever the whale surfaces, over the course of weeks to months, before eventually falling out. These tags are also especially useful for species that are rarely seen, such as beaked whales. Satellite-linked dive tags deployed on Cuvier’s beaked whales revealed, in a precise way, the astonishing extremes of their foraging dives for squid and fish—over 137.5 minutes of breath holding, 2,992 meters deep—data that set new dive records for a mammal. If the idea of holding your breath for over two hours doesn’t alarm you, imagine doing it while chasing your dinner to a depth of nearly two miles.

Tag data combined with tissue samples taken from biopsy darts tell us that these humpback whales feeding in the western Antarctic Peninsula are merely seasonal visitors for the austral summer. By early fall, they depart the icy bays, cross the great Circum-Antarctic Current that rings the seventh continent, and undertake various paths over thousands of miles to arrive at temperate latitudes. At Wilhelmina Bay the overwhelming majority of humpbacks return to the low latitudes of the Pacific coasts of Costa Rica and Panama to mate and give birth before returning to the Southern Ocean for the next austral summer to feed.

We eventually retrieved the tag, along with its data, and continued to Cuverville Island, on the other side of Wilhelmina Bay. As the Ortelius maneuvered out of the Gerlache and toward the island, I watched from the ship’s stern as we passed icebergs more massive than any I had yet seen. Their fragmented sides, a hundred feet high, were etched in luminous, milky blues and grays. They held light from sea to sky, glowing in unearthly ways, as if they could not have been formed on this planet. And of course they were mostly sheathed underwater, which was a bit of an ominous thought; the Ortelius kept a careful distance. But the incomprehensibility of something as overwhelming as an iceberg is belied by its transience: even the largest ones, platforms the size of cityscapes, will eventually shed their layers of ice, annealed over hundreds of thousands of years, and become part of the sea.

Scattered around the peninsula are several islands like the one we approached, islands that served as barely inhabitable platforms for whaling operations in the early and midtwentieth century. Today the only remnants of human civilization are occasional concrete pylons with bronze plaques identifying the area as an open-air heritage site, and leftover whale bones. After we hauled our rubber boat up on the rocks, I walked toward the spoil piles of green-stained and weathered whale bones, strewn like spare lumber at a construction site.

Reading whale bones is what I do, although sometimes I feel like the bones find me. I’ve spent so much time searching for them, cataloging them, and puzzling over them that my brain immediately recognizes even the slightest curve or weft of bone. Whale bones tend to be relatively large, so finding them is often largely a matter of making sure that you’re in the right neighborhood—it shouldn’t have been much of a surprise, especially on the grounds of an abandoned whaling station. On the island I mentally inventoried the first assemblage I encountered, as I dodged foot-tall gentoo penguins scrambling at my feet: ribs, parts of shoulder blades, arm bones, and fragments of crania. They clearly belonged to rorqual whales, about the size of humpbacks, or possibly even fin whales. Some of the more intact vertebrae were artfully balanced upright on the shoreline, probably posed by Antarctic tourists, passing through the peninsula by the thousands in the austral summer and looking for a perfect photograph.

If these bones belonged to humpback whales, it would not be surprising, given the abundance of this species out around Antarctica today. It’s likely that some of the whales that we tagged were descendants of these individuals, belonging to the same genetic lineage. But history tells us that if you turned back the clock a century, humpbacks probably wouldn’t have been the only ones here: blue and fin whales would have numbered in the hundreds, if not thousands; minke whales, beaked whales, and even Southern right whales would also have been part of the community. Ari has seen only one right whale out of the thousands of whales that he’s observed over fifteen years in the area. Southern right whales have barely recovered from two hundred years of whaling, and we know little about where they go besides their winter breeding grounds along protected coastlines of Australia, New Zealand, Patagonia, and South Africa.

It’s not just right whales that vanished. There’s no memory or record of just how many of any kind of whale there was in the Southern Ocean, in terms of their abundance, before twentieth-century whaling killed over two million in the Southern Hemisphere alone. However, as whale populations in this part of the world slowly recover from this devastation, we’re beginning to see what that past world might have looked like. On an expedition in 2009, Ari and his colleagues documented an extraordinary aggregation of over three hundred humpbacks in Wilhelmina Bay, the largest density of baleen whales ever recorded. “There is no external limit on these whales because there is just so much krill. They literally cannot eat enough before they need to leave,” Ari reflected. “That incredible resource base means that it’s just a matter of recovery time for whales—and I think what we saw in the bay that year was a glimpse of what their world was once like, before whaling.” On the whole, humpbacks have recovered to only about 70 percent of their prewhaling numbers in the Southern Ocean, although along the peninsula their population size has nearly returned to the best estimates of prewhaling levels at the start of the twentieth century.

I paused on a guano-free ledge to record a few observations about the bones’ weathering and their measurements in my field notes. To the southwest, the sky churned in a dark gray, portending wind and snow, and I felt a chill creep into my damp toes and fingertips. I pulled off my gloves and reached for a disposable hand warmer in my jacket pocket. Lodged in a mess of receipts and lozenge wrappers was a note my son had left me on the kitchen counter back home:

Im gona mis you

wen you go to

anaredica.

The night before I left my home in Maryland we traced the expedition route on a plastic globe. When he wanted to know how far away eight thousand miles was in inches, I didn’t tell him the answer that I wanted to, which was “Too far.” I reassured him that the passage was safe and that we would stay warm. “I’ll think about you when we drink hot cocoa,” I offered, dressing up my own concerns with a good smile.

As we pulled away from Cuverville Island to return to the Ortelius, the swirling clouds began to send down flurries, covering us in thick, wet snow. The boat bumped hard against the waves, and we saw humpbacks surfacing far off in the distance, the wind pushing their blows quickly behind them. The sight of those living, breathing, feeding whales in the same view as the island with beach-cast bones made me feel as though I could see the present and past simultaneously, each telling us facts that the other vantage could not. The bones on Cuverville Island and Ari’s tagging work in the Gerlache were each a unique window into the story of humpback whales in the Antarctic, though these views were terribly incomplete: the past represented by mere bones crumbling on remote shores, what we know today limited to a few hours’ or days’ worth of data collected by a hitchhiking recorder on whales’ backs.

Scientists tend to operate within intellectual silos because of the years of training and study that it takes to know about any single part of the world. But the best questions in science arise at the edges. Ari and I both want to know how, when, and why baleen whales evolved to become giants of the ocean—Ari wants to know more about their ecological dominance today, and I want to know what happened to them across geologic time. The answer to the basic question about the origin of whale gigantism requires pulling data and insights from multiple scientific disciplines, which is another way of saying that we need the perspectives of different kinds of science—and scientists—to untangle the monstrous challenges of the nearly inaccessible lives of whales. That’s why a paleontologist like me was on a boat tagging whales at the end of the Earth: I needed a front-row seat to know exactly what we can hope to know from a tag. But answering the questions that most captivate me about whales requires more than just a single tag. It means wrapping my arms around museum specimens, handling microscope slides, paging through century-old scientific literature, and wading knee-deep in carcasses.

The wind sapped the last warmth from my already-wet gloves and whipped through openings around my hood as I held tight to the ropes on the gunnels. The first scientists to visit this place, over a hundred years ago, didn’t have the luxury of disposable hand warmers. They suffered more brutally than we can really imagine, with less certainty of safe return. In these narrow margins they must have wrestled with the tension that overcomes scientists in the field: the desire to apprehend something almost unknowable against the tolls of living a world away from civilization. I patted my son’s note, folded safely inside my jacket pocket. Hot cocoa sounded just right.

I was never a whale hugger. I didn’t fall asleep snuggling stuffed whales or decorate my room with posters of humpbacks suspended in prismatic light. Like most children, I went through phases of intense study: sharks, Egyptology, cryptozoology, and paleontology. The curriculum was loosely inspired by my small curio cabinet crammed with a bric-a-brac collection of gifts and found treasures: abalone shells from my parents’ friends in California and fluorite from a great-aunt in New Mexico sat next to trilobites and fossil ferns that I had collected on family trips to Tennessee and Nova Scotia (good fossils being hard to come by on the island of Montreal). My collection was a tangible means to escape, across geography and time, as I read ravenously about dinosaurs, mammoths, and whales under the tacit encouragement of my parents, professors who recognized this type of aimless curiosity.

During one of my immersive phases, I came across a distribution map that showed the location of whale species around the world. With my finger I traced the range of blue whales, the largest of all whales, as it went right up the St. Lawrence River, which bordered my neighborhood. I wondered about my chances of seeing a blue whale casually surfacing in the distance near my house. The thought of a local blue whale was a reverie that often arose in my mind as a kid, although it took two decades for me to return to it in earnest, as a scientist.

Some branches on the tree of life become quite personal, for reasons that are difficult to explain. We seek reflections of parts of ourselves in beings seemingly close to us—the disdain of a house cat or the perseverance of a tortoise—but in the end these species are distinctly other, refashioned by evolution and eons of time away from our shared ancestry. Those differences are accentuated to the furthest degree in whales; they seem mostly other—otherworldly, really—and that makes them both fascinating and enigmatic. They embody an incongruity that is vexing because they betray their mammalian heritage in so much of what they do, yet they look and live so far apart from us. Their size, power, and intelligence in the water are astonishing because they’re unparalleled, yet whales are benign and pose no threat to our lives. They are almost a human dream of alien life: approachable, sophisticated, and unscrutable.

I don’t malign whale huggers and dolphin lovers, even if I wrinkle my nose at the rhapsodic celebrations of armchair experts. Yes, whales and their lives are superlative, foreign, and well worth epic prose. But their amazing qualities are just starting points for me, as a scientist. Whales aren’t my destination: they are the gateway to a journey of discovery, across oceans and through time. I study whales because they tell me about inaccessible worlds, scales of experience that I can’t feel, and because the architecture of their bodies shows how evolution works. By rock pick, knife blade, or X-ray, I seek the corporeal evidence they provide—their fossils, their soft parts, or their bones—as a tangible way to anchor questions that surpass the bounds of our own lives. Whales have a past that reaches into Deep Time, over millions of years, which is important because some features of these past worlds, such as sea level rise and the acidification of ocean water, will return in our near-future one. We need that context to know what will happen to whales on planet Earth in the age of humans.

Whales are so very unlike the furry, sharp-eyed, tail-wagging, baby-nuzzling animals we think of when it comes to our mammalian relatives. First off, whales are among the few mammals that live their entire lives in the water. The only fur to be found on their bodies is the hairs that dot their beaks at birth. Although whales possess the same individual finger bones that you and I do, their phalanges are flattened, wrapped together in a mitt of flesh, and streamlined into bladelike wings, no hooves or claws to mar their perfect hydrofoils. Hind limbs exist only as relics in a handful of species, bony remnants tucked deep within muscle and blubber. A whale’s backbone ends in a fleshy tail fluke, like a shark’s; but unlike a shark or even a fish, whales swim by flexing their backbone up and down, not side to side. In short, they look nothing like squirrels or monkeys or tigers, but whales still breathe air, give birth, nurse their young, and keep company with one another over their lifetimes.

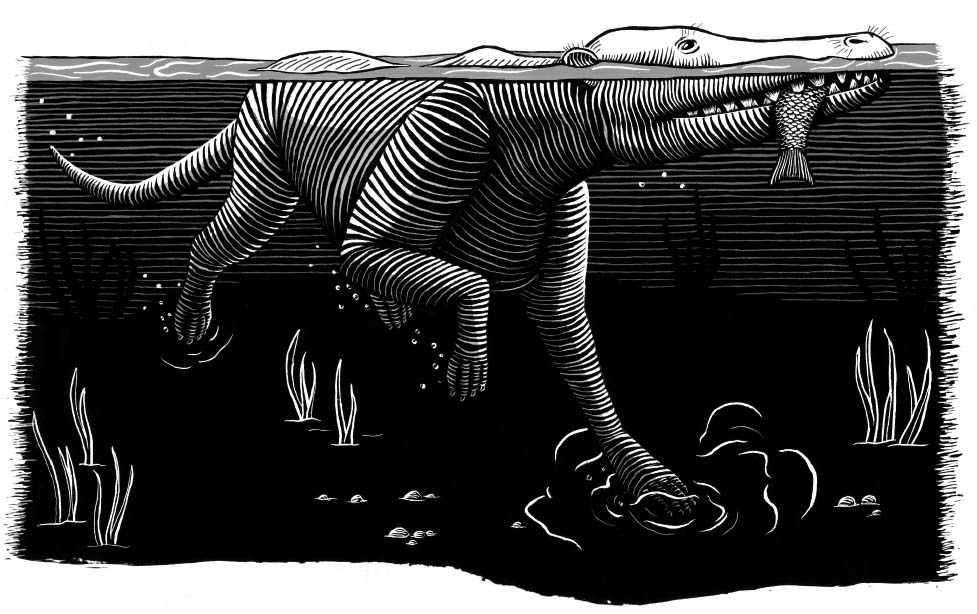

Fossils tell us the earliest whales were more obviously, visibly mammalian. The first whales had four legs, a nose at the tip of their snout, and maybe even fur (up for some debate among paleontologists, as fur doesn’t readily fossilize). They had sharp, bladelike teeth and lived in habitats that ranged from woodlands with streams to river deltas, occasionally feeding in the brackish waters of warm, shallow equatorial coasts. The oldest fossils of these land-dwelling, four-legged ur-whales come from rock sequences around about fifty million to forty million years old in the mountain ranges of Pakistan and India. At the time, the Indian subcontinent had not yet collided with Asia and sat in the middle of the forerunner to the Mediterranean Sea, called the Tethys sea, which split the Old World at the equator.

The skeletons of most of these first whales were the size of a large domestic dog. Because they lived on land, you won’t find the flattened arm and finger bones we see in whales today—instead their limb bones are round and weight bearing, and their hands and feet end in elegant, delicate phalanges. Their tail, as far as we can infer from the available bones, did not end in a fluke. Their Latin names give some clues about their provenance or what makes them special. Pakicetus, for example, originates from an area that is now Pakistan, but was once an island archipelago where early whales climbed in and out of streams. Ambulocetus, a low-slung early whale with body and skull proportions like a crocodile, has a name that translates as “ambulatory, or walking, whale.” Maiacetus, one of the rare early whales for which we have a near-complete skeleton, earned its name from fetal bones preserved near the abdominal cavity of the original specimen—the mother whale. Today’s whales all give birth tail first; the rear-facing position of the fossilized fetal Maiacetus showed that whales at this evolutionary stage still gave birth on land, headfirst.

The combination of four legs, phalanges, and cusped teeth is found in no whale alive today. What made these ancient creatures whales in the first place is subtle, lodged deep in their skeletons. That’s a good thing for us because these hard parts stand a chance of being preserved over tens of thousands of millennia. One of the most important features is the involucrum, a fan-shaped surface on the outer ear bone, rolled like a tiny conch shell. Pakicetus has an involucrum, as does every other branch on the whale family tree subsequent to it. The involucrum is one key trait, along with small clues in the inner ear and braincase, that the earliest whales share exclusively with today’s whales and no other mammals. In other words, it’s a feature that makes them whales and not something else. It’s unclear whether the trait gave Pakicetus an advantage for hearing on land, but later lineages of early whales co-opted it to hear directionally underwater, using a connection between the outer ear bones and the jawbones. Tens of millions of years later, the involucrum (and underwater hearing) persists in today’s whales, from porpoises to blue whales.

Pakicetus, a land dweller, swims in an Eocene streambed.

Fifty million years of whale evolution can be split into two major but unequal phases. The first deals with the transition of whales from land to sea in less than ten million years; the earliest land-dwelling whales all belong in that first phase—even at their most aquatic, they still retained hind limbs that could have supported their weight on land. The second phase covers everything that happened once whales evolved fully aquatic lives, for the remaining forty or so million years, until today. Throughout both of these phases, extinction dominates as a constant background theme because, as with the vast majority of animal lineages on the planet, most all the whale species that ever evolved are now extinct. While they are the most diverse marine mammal group today, numbering over eighty species, the fossil record documents over six hundred whale species that no longer exist.

The first phase of whale evolution is fundamentally about transformation: the tinkering and repurposing of structures from an ancestral state (originally for use on land) to a new one, in aquatic life. Transformation requires an initial state, and some starting points in evolution can be difficult to discern. For example, hearing, sight, smell, and taste are all senses that evolved for nearly 300 million years on land before the first ancestors of whales took to the sea. While it’s convenient to think of the reshaping of hands into flippers in whales as an undoing, that’s a mistake: whales didn’t undo 300 million years of terrestrial modifications. They did not, for example, recover gills. Instead, the story is far more interesting. Whales worked with what their ancestors had as land animals, modifying many anatomical and physiological structures for a new use rather than some phantasmagoric evolutionary reversal.

The second phase, after whales got back in the water, encompasses any whale lineage obliged to spend its life exclusively in the water; this phase also spans all of the consequences that arise from that constraint. You can think of evolutionary innovation as a hack on constraint. In other words, novelty in evolution is the appearance of a totally new structure, such as baleen, that confers not just a slight advantage to those who possess and inherit it but shifts their descendants into a completely new dimension of adaptation. The second phase of whale evolution, when innovations such as filter feeding and echolocation appear and fuel the diversification of today’s whales, stretches in time from the first aquatic whales, about forty million years ago, to the present day, including all living cetaceans, along with hundreds of extinct forms in between.