Полная версия

EPIDEMICS in Ancient Egypt

Victoria Goldwyn

EPIDEMICS

IN ANCIENT EGYPT

A Concise Overview on

Ancient Survival Strategies

in Uncertain Times

EPIDEMICS

in Ancient Egypt

A Concise Overview on Ancient Survival Strategies in Uncertain Times

© 2022 Victoria Goldwyn

Victoria Goldwyn

c/o AutorenServices.de

Birkenallee 24

36037 Fulda

Germany

Translated from German language. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or processed, duplicated or distributed using electronic systems without the written permission of the publisher.

Cover Design: inhouse

Created in Germany.

www.missing-the-pharaoh.com

hello@missing-the-pharaoh.com

“Follow Your Heart as Long as You Live.”

From the Ancient Egyptian Wisdom of Ptahhotep, 5th Dynasty, 2504–2347 B.C.

Table of Contents

INTRODUCTION

MAGIC

Sources of Magical Traditions

Heka & Akhu – The Power of Magic

The Magician

Magical Tools and their Application

The Spell

The Procedure of Magical Manifestation

MEDICINE

Definition of Health and Disease

Disease and its Treatment

Sources of Medical Traditions

The Medical Papyri

Summary

ARCHAEOLOGICAL EVIDENCE

Magical Stelae

Amulets

Scarabs

Magic Wands

EPIDEMICS

Introduction

Pap. Edwin Smith, the Epidemic Papyrus

There is Something in the Air

Hygiene Measures

Causes of Epidemics

Summary

Sources and Further Reading

INTRODUCTION

A Concise Overview on

Ancient Survival Strategies

in Uncertain Times

T

his short reading is about magic and medicine in Ancient Egypt. It is addressed to all those who have never heard anything on this subject. It is intended to reach those looking for a concise but precise introduction to the topic and aims to answer questions about what the Ancient Egyptians did to counter diseases.

Magic and medicine: Why are these two fields connected here? After all, medicine is science, and magic is opposed to it, right? Well, for the Ancient Egyptians, both belonged together. Magic and medicine were not mutually exclusive. The physician could be a magician and a priest at the same time, and both professions were educated in the same place, in the so-called House of Life. In the Ancient Egyptian language, it was called per ankh. This was a school where astronomers, astrologers, and other scientists also received their education. At that time, the magical creation of things belonged equally to the necessary knowledge of a healer as the treatment of injuries with herbal tinctures. So, there was not always a sharp separation of disciplines.

When treating the sick, the Ancient Egyptians also displayed practical creativity. An impressive example is this oldest prosthesis for a toe found in Egypt. Experienced specialists in antiquity created simple replacements of body parts made of cedarwood and leather as early as 600 B.C.

People who had lost a body part due to an accident, illness, or battle were thus able to lead a halfway everyday life again. The archaeological artifact, shown in the picture below, of a prosthetic toe belonged to the daughter of a priest. She probably suffered from diabetes and had to have her toe amputated. Experts found that this new prosthetic toe was so well adapted to the human physiognomy that the patient could probably walk very well with it.

Fig. 1.: Prosthetic toe from Ancient Egypt made from leather, linen and cedarwood.

In the following, I will now first provide you with basic knowledge about both fields, magic and medicine. These overviews are essential for understanding why magic and medicine are so closely related. Next, I will address what illness meant to the Ancient Egyptians in the first place. And you will learn why magic was not quackery to them. We will look at selected archaeological objects, which give us valuable clues about healing treatments and magical acts for the restoration of health or the manifestation of a pleasant existence in the afterlife.

In the central section about epidemics in Ancient Egypt, we will look at historical text sources about treatments and magical acts for restoring health and how they tried to prevent diseases.

This is a pretty current topic: In Ancient Egypt, too, people struggled with outbreaks, which they had difficulty controlling over a long period. What we today call an epidemic or – on a global scale, a pandemic – was also known to the Egyptians. This section is about the behavior of the Ancient Egyptians during plaguess. How did they perceive the epidemic in the first place? And what did they do to prevent it from spreading?

MAGIC

Sources of Magical Traditions

The historical source situation to magic in Ancient Egypt is various. Besides archaeological evidence, from which we can deduce today, how the Ancient Egyptians performed magical acts, we have much textual evidence. These are not only inscriptions on material legacies. Written evidence even provides us with an extensive repertoire of magical spell literature, partly in the form of individual spells and comprehensive collections of spells on papyrus.

These texts concern different recipients and pursue other goals. However, categorizing the texts into protective spells, defensive spells, healing spells, and so on can be problematic. It can happen to all historical evidence that we try to put into a system according to our current standards. The Ancient Egyptians did not think in such black and white categories. They were aware that the development of their lives and the events they experienced were always linked to higher powers. And these powers, be they positive like the well-known deities of the Ancient Egyptian pantheon or harmful like demons, could be and were addressed on several levels: through physical actions and treatments, invocations, and prayers. And so, it is not surprising that healers also applied magical formulas cumulatively. But to make the complex world of Ancient Egyptian magic and medicine comprehensible to us today, we can certainly categorize certain spells for our orientation.

We have texts that support the process of transfiguration. In Ancient Egypt, transfiguration was an essential part of their faith. Sakhu is the Ancient Egyptian term and stands for the transformation of the soul of a deceased person into an Akh, the light-filled ancestral spirit. This is the time of a dead person’s ascension to the stars.

Other texts describe the transformation of the form of a deceased person into the manifestation of a God, animal, or plant. Other spells aimed to provide nourishment for the dead person in the afterlife. As you can see, these are mainly spells from the funerary realm. They were often used in a funeral ceremony to support the safe passage of the deceased into the afterlife and provide his life with everything he needed on the other side.

Powerful spells could also be love spells to manipulate someone into falling in love with the spell-caster or another person. Even unpleasant neighbors or personal enemies could become the targets of particular spells, similar to the African voodoo tradition. However, these classical damage spells, which we can assign to the black magic, are relatively rarely documented in Ancient Egypt. These are often spells against intruders or enemies of the country or potential grave robbers who could disturb the passage of the dead into the afterlife. These execration texts, the technical term for this is the German word Ächtungstexte, are therefore often found in the context of burials.

The large group of protective spells also includes those healing spells specifically directed against an illness or a condition for which a demon is held responsible, such as a fever demon.

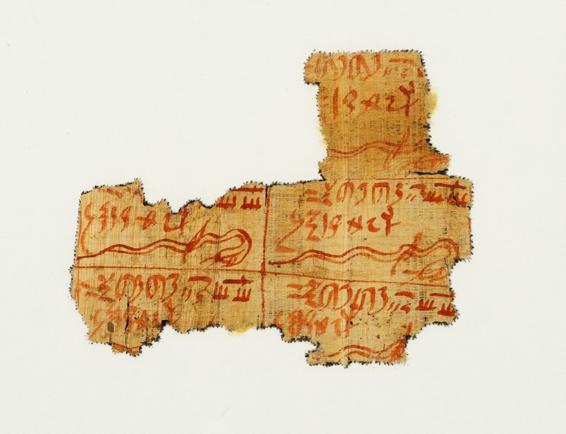

Fig. 2.: Egyptian magical text on papyrus in coptic language.

Heka & Akhu – The Power of Magic

The power of magic was standard for the Ancient Egyptians. From the simple farmer to the Pharaoh, everyone integrated this creative energy into his everyday life. They even had their special terms for this unique force: Heka and Akhu.

Heka and Akhu are often used synonymously in Egyptology. They describe energies, which are considered as magic power or spell power. They stand for something supernatural, which gives access to higher knowledge and solves concrete challenges of the real world.

Heka is the greatest, all-pervading creative power. It was so important for the Ancient Egyptians that priests of the Roman times called Heka, the first work of Chnum. Chnum was the Creator God in Egyptian mythology who created people, plants and animals from clay on his potter’s wheel. With the help of Heka, the Egyptians connected their imagination with the ability to create.

First, they visualized – so they created.

Heka could also show itself as light and was both a desired and feared energy. Often, the Egyptian was downright afraid of being cast an evil spell that could prevent his carefree existence in the afterlife.

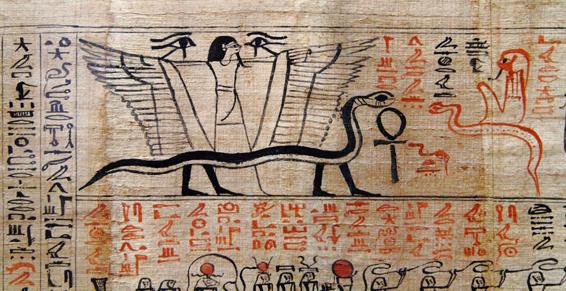

The Amduat, the so-called Underworld Book, is a series of texts that divides the life cycle and transformation from this world to the afterlife into so-called 12 hours. In the 7th hour, it even describes that the Sun God Ra has magical help from Isis and Heka in crossing the water when Apophis, the Great Serpent, threatens him.

Heka is so powerful that it can even create and cure diseases. To achieve this, Ancient Egyptian doctors also used magic. Some also called themselves Priests of Heka, which was supposed to express their extraordinary power.

Besides, Heka also stands for the child-God of the same name, Heka, the God of Magic. This God forms the connection between the almighty world of Gods, which the Ancient Egyptian feared, and his endeavor to take things into his own hands utilizing magic.

What would be unthinkable in many modern religions was typical for the Egyptians: From literary sources such as the Teachings of Merikare, for example, we know that Heka, the power of magic, was given to man as a defensive weapon. So, religion and magic did not contradict each other.

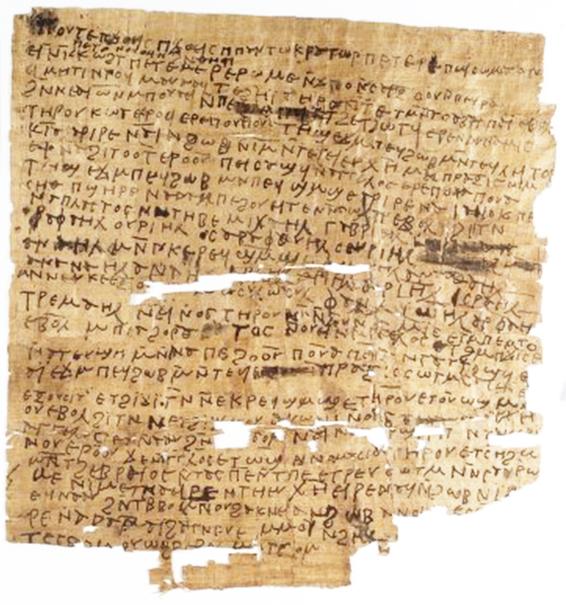

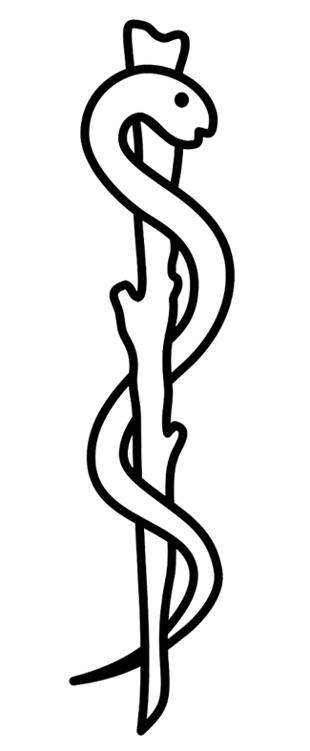

The child-God Heka was depicted in the typical child-God pose with his hand or finger at his mouth and the characteristic child curl on the side of his head. He is thus iconographically comparable to the Horus Child Hor-pa-chered. Hor-pa-chered means Horus-the-Child and was called Harpocrates in Ancient Greek. Another exciting aspect of the representation of the God Heka is that he sometimes shows up with two snakes in his hand. So, it is not surprising that the nowadays well-known Aesculapian staff with the coiling snake is still an often-used symbol for medicine.

Fig. 3: Heka, the child-God.

Fig. 4: Scene from the underworld book Amduat on a Papyrus.

Fig. 5: The Rod of Asclepios, the Greek God of Healing and Medical Arts.

The Magician

We can identify two groups of people in Ancient Egypt who could be considered magicians:

There were simple magical practices that they performed, for example, by using an amulet. These did not require such deep knowledge and could be practiced by anyone. Most of the time, the corresponding spells were relatively easy to recite. One practiced, so to speak, magic in one’s affairs for the minor aches and pains of everyday life.

The other group was those who, as healers and magicians, were consulted by others for more severe problems. These were the experts, so to speak, who had acquired their extensive sacred knowledge in the House of Life, per ankh. The mage who wanted to help the needy used this sacred knowledge and a vast repertoire of spells. They passed it on only to the chosen ones in the framework of an initiation. The experts specialized in particular fields, which their titles could recognize: Heka:ooh (magician), Sa:ooh (a specialist, who performed magical protective actions on deserts and quarry expeditions), Wab Sekhmet (Sekhmet priest), Khereb Sereket (the scorpion summoner), etc. However, the most important spell-caster and priest was the so-called priest of reading Cheri Hebet, who was active in funerary or sacred cults and many magical acts in everyday life.

It is difficult to distinguish between a physician, a magician, and a priest because job titles are often intertwined. For example, a Soo:nooh physician could also be a Sa:ooh magician. The Sekhmet priest could indicate by his chain of names that he was the head of the Heka:ooh magicians. This possible triple occupation, which means physician, priest, and magician, was usual for the Ancient Egyptians. Only for us, the analysis of these healing concepts is sometimes a challenge because, in our modern society, there is a strict separation between science and religion or magic.

Fig. 6.: Fragment of a magical papyrus, ca. 712–525 B.C., Third Intermediate Period–Saite Period.

Magical Tools and their Application

The Ancient Egyptians believed that there was a mysterious connection between them and the world of the Gods, which could be activated by saying holy words. Moreover, they believed they could have the divine powers at their disposal by saying prayers.

But the strongest Ancient Egyptian principle about magic is the belief in a direct connection between the spoken word or the image shown and the desired event or circumstance.

In other words, the Egyptian was so intensely aware of the power of the word and the image that his entire theological, spiritual worldview was based on this. Therefore, word and image magic is part of the Egyptian’s basic understanding of creative processes.

The principles of analogy and sympathy were the most crucial building blocks of this magical practice in profane everyday life and the sacred and funerary realm.

An analogy here means the imitation and equation of two or more things. Sympathy is the use of similarity between things, in Latin called similia similibus.

Magical tools can be of material or linguistic nature.

Material magical tools could be:

materials and the symbolism of their colors,

amulets,

the entire funerary equipment, including tomb models, servant figures, and ushabtis,

remedies,

magic knives (or birth tusks)

offerings or also

concrete objects symbolizing the enemy.

By linguistic magical tools, we understand, for example:

recited texts, hymns, and litanies (repeated chanting prayers),

pyramid texts,

coffin texts,

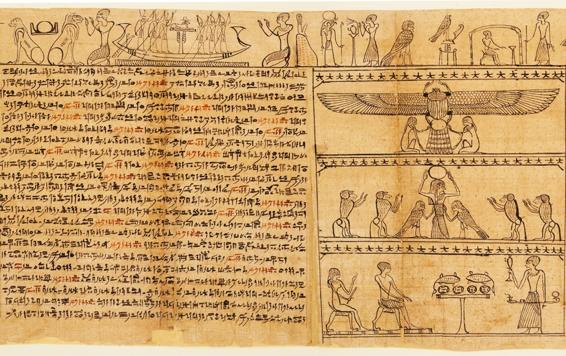

the Ancient Egyptian Book-of-the-Dead,

afterlife guides such as the Amduat,

magical letters to the dead ancestors,

and much more.

They performed spell actions for preventive protection. The spells worked as concrete defensive steps to create the desired event or restore a previous state.

This took the form of rituals through

incenses

libations (pouring liquids)

symbolic smashing and destruction

real or symbolic slaughter

gestures or

offerings.

Even the compliance to chastity rules and the cultivation of purity can be interpreted as part of a magic act as soon as it happened with the intention of a concrete, foreseeable manifestation.

Fig. 7: Book-of-the-Dead of the priest of Horus, Imhotep, ca. 332–200 B.C., Early Ptolemaic Period.

The Spell

Each magical act came along with a spell, which was called ra. Another Ancient Egyptian term is shenet, the invocation. Sometimes it was also written down as sa:ooh, which means protective spell. Collections with the records of many spells were referred to simply as medjat, the book, or as ra:ooh, the plural form of ra.

The archaeological evidence from which we draw our present knowledge of the spell-casting practices of the Ancient Egyptians is usually papyri, ostraca, statues, stelae, and other objects.

The spells very often follow a unique scheme:

a heading, the so-called spell title,

the core text of the spell, and

an instruction for handling or commentary.

The latter often contains a listing of materials, ingredients, or similar and is accompanied by instructions for processing and application. This is practically comparable to the package leaflet of modern drugs.

Recipients of the spells are either the good deity, which is to produce the desired state, or the enemy, or the opposing energy, for example, a demon, whose influence is to be weakened. It is interesting to note that the recited text presents the facts in different ways:

stating, that is, the simple statement and description of a condition.

narrative, that is, telling a story around the desired state, or

discursive, which means creating an argument with a deity.

In terms of content, spells often reflect the mythological stories surrounding the Gods Isis and Osiris, the battle of the God Horus against the God Seth, or the narratives surrounding the Sun God Ra. Thereby it is always first about the determination of danger, for example, the injury of Osiris and his subsequent healing. Thus, an analogy is always created using known legends.

The Procedure of Magical Manifestation

Equipped with these standardized spells, a magician could now perform the actual magical ritual. In doing so, he had several options, each of which depended on the purpose of the action. In most cases, this was done by recitation and application.

In the recitation, the magician repeated the magic spells and at the same time could add material equivalents to strengthen the manifestation, for example, by untying a knot in a rope. Spells could also be chanted or shouted.

During application, objects charged with the spells could contact each other to produce the desired effect, such as direct contact between an amulet and the injured body part.

Ideally, recitations were performed in the morning. According to the belief of the Ancient Egyptians, the powers of darkness lost strength at this time. They began to recede with the disappearance of the night.

The magic act and the corresponding spells were subject to strict secrecy, a prerequisite for their effectiveness. The knowledge of the identity of the God or demon caused a disease often played a unique role.

If the magician knew his name and could address the God or demon directly with his spells, this gave him power over him.

The magician then puts himself in the place of the God or demon with the powerful formula

>> I am...

at the beginning of a magical procedure. In the end, often a disclaimer took place, and the magician rolled back the entire thing again in which he conjured,

>> It is not I who says this, but the God.

This procedure shows impressively how the Ancient Egyptian healer and magician used the sacred world’s powers.

The Ancient Egyptian magical acts referred to various conditions that were either fought against or realized positively.

Particularly prevalent were the magical acts against concrete or abstract dangers. Such dangers could come from wild animals, such as scorpions or snakes, and invisible or intangible demons. In addition, the feeling of being pursued by the evil eye emanating from unfavorable or even hostile-minded other people already existed in Ancient Egypt. Therefore, the Ancient Egyptian could defend himself prophylactically or in the concrete case of suspicion against it with a protection and defense spell.

According to the belief of the Ancient Egyptians, the work of deities could be the cause of the occurrence of diseases. So, the healing spell against a disease in a person’s body was a proven method to restore the original health. Therefore, in the following section about Ancient Egyptian Medicine we will now deal in detail with the sources of magical healing practices of the Ancient Egyptians, their mechanisms, and their archaeological evidence.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.