Полная версия

Why the Whales Came

Why the

Whales Came

Also by Michael Morpurgo

Arthur: High King of Britain

Escape from Shangri-La

Friend or Foe

The Ghost of Grania O’Malley

Kensuke’s Kingdom

King of the Cloud Forests

Little Foxes

Long Way Home

Mr Nobody’s Eyes

My Friend Walter

The Nine Lives of Montezuma

The Sandman and the Turtles

The Sleeping Sword

Twist of Gold

Waiting for Anya

War Horse

The War of Jenkins’ Ear

The White Horse of Zennor

The Wreck of Zanzibar

For Younger Readers

The Best Christmas Present in the World

Conker

Mairi’s Mermaid

The Marble Crusher

Why the

Whales Came

MICHAEL MORPURGO

CONTENTS

1 Z.W.

2 Island of Ghosts

3 Messages in the Sand

4 The Birdman

5 The Preventative

6 The King’s Shilling

7 Samson

8 Castaways

9 31st October 1915

10 Dawn Attack

11 Last Chance

12 The End of it All

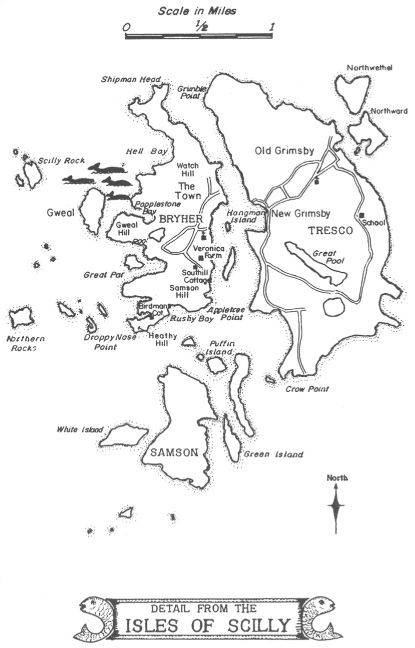

I was brought up on Bryher, one of the Isles of Scilly. You can find them on any map, a scattering of tiny islands kicked out into the Atlantic by the boot of England.

I was about ten years old when it all happened. It was April 1914.

Gracie Jenkins, 1985

1 Z.W.

‘YOU KEEP AWAY FROM THE BIRDMAN, GRACIE,’ my father had warned me often enough. ‘Keep well clear of him, you hear me now?’ And we never would have gone anywhere near him, Daniel and I, had the swans not driven us away from the pool under Gweal Hill where we always went to sail our boats.

Daniel and I had built between us an entire fleet of little boats. Fourteen of them there were, each one light blue with a smart white stripe along the bulwarks. I remember well the warm spring day when we took them down to the pool in father’s wheelbarrow. We had just the gentle, constant breeze we needed for a perfect day’s sailing. We launched them one by one and then ran round to the far side of the pool to wait for them to come in. It was while we were waiting that a pair of swans came flying over, circled once and then landed in the middle of the pool, sending out great waves in their wake. Two of our boats keeled over and some were eventually washed back to the shore; but we had to wade in after the others to retrieve them. We tried shouting at the swans, we even threw sticks at them; but nothing we did would frighten them away. They simply ignored us, and cruised serenely around the pool, preening themselves. In the end it was we who had to leave, piling our boats into the wheelbarrow and trudging defeated and dejected home to tea.

For some days after that we tried to occupy our pool again, but the swans always seemed to be on the lookout for us and would come gliding towards us in a meaningful, menacing kind of way. They left us in no doubt that they did not want us there, and that they would not be prepared to share the pool with anyone.

So reluctantly we gave up and took our boats to nearby Popplestone Bay, but we found it was so windy there that even on the calmest of days our boats would be capsized or beached almost as soon as we pushed them out. And then one day the fastest boat in the fleet, Cormorant it was, was carried out to sea before we could do anything about it. The last we saw of her was the top of her yellow sail as she vanished in the trough of a wave. That was the last straw. After that we never sailed our boats from Popplestone Bay again. We were forced to look for somewhere else.

The beach on the sheltered coast of the island opposite Tresco would have been perfect, for the water was calmer here than anywhere else around the island, but there was always too much happening there. It was the hub of the island. Fishing boats were for ever coming in and going out, leaving great tidal waves behind them big enough to swamp our boats; and the children were often fishing off the quay or splashing through the shallows. Then there were Daniel’s brothers and sisters, most of whom always seemed to be on that beach mending nets and lobster pots or painting boats. Of all of them, the one we most wanted to avoid was Big Tim, Daniel’s eldest brother, and our chief tormentor; and he was always there. The one time we had tried to sail our boats there, he had come with his cronies and bombarded our fleet with stones. They had managed to break two of the masts, but to our great delight and their obvious disappointment, none of our boats was sunk. Even so, we did not want to risk it again. We had to find somewhere secret, somewhere where no one came and where the water was still enough for us to sail our boats. There was only one place left that we could go – Rushy Bay.

Rushy Bay was forbidden territory to us, along with most of the west coast of Bryher. The pool under Gweal Hill and the beach on Popplestones beyond was as far as any of us children were allowed to go in that direction. We never asked why, for we did not have to. We all knew well enough that the west coast of the island was dangerous, far too dangerous for children, whatever the weather. Mother and Father reminded me repeatedly about it, and they were right to do so. At Shipman’s Head and Hell Bay there were black cliffs hundreds of feet high that rose sheer from the churning sea below. Here even on the calmest of days the waves could sweep you off the rocks and take you out to sea. I had been there often enough, but always with Father. We used to go there for firewood, collecting the driftwood off the rocky beaches and dragging it above the high-water mark to claim it for our own; or we would go for the seaweed, piling the cart high with it before going back home to dress the flower pieces or the potato fields. But I never went alone over to that side of the island, none of us ever did.

There was another more compelling reason though why we children were warned away from Rushy Bay and Droppy Nose Point and the west coast of the island, for this was the side of the island most frequented by the Birdman of Bryher. He was the only one who lived on that side of the island. He lived in the only house facing out over the west coast, a long, low thatched cottage on Heathy Hill overlooking Rushy Bay itself. No one ever went near him and no one ever spoke to him. Like all the other children on the island, Daniel and I had learnt from the cradle that the Birdman was to be avoided. Some said the Birdman was mad. Some said he was the devil himself, that he fed on dogs and cats, and that he would put spells and curses on you if you came too close.

The little I saw of the Birdman was enough to convince me that all the stories we heard about him must be true. He was more like an owl, a flitting creature of the dark, the dawn and the dusk. He would be seen outside only rarely in the daylight, perhaps out in his rowing boat around the island or sitting high on his cart; and even in the hottest summers he would always wear a black cape over his shoulders and a pointed black sou’wester on his head. From a distance you could hear him talking loudly to himself in a strange, unearthly monotone. Maybe it was not to himself that he talked but to the kittiwake that sat always on his shoulder or to the black jack donkey that pulled his cart wherever he went, or maybe it was to the great woolly dog with the greying muzzle that loped along beside him. The Birdman went everywhere barefoot, even in winter, a stooped black figure that lurched as he walked, one step always shorter than the other. And wherever he went he would be surrounded by a flock of screaming seagulls that circled and floated above him, tirelessly vigilant, almost as if they were protecting him. He rarely spoke to anyone, indeed he scarcely even looked at anyone.

Until now it had never even occurred to either Daniel or me to go alone into the forbidden parts of the island, nor to venture anywhere near the Birdman’s cottage. After all, the island was over a mile long and half a mile across at its widest. We could roam free over more than half of it and that had always been enough. But Daniel and I had to have somewhere to sail our boats. It was all we lived for, and Rushy Bay was the only place we could do it. Even so I did not want to go there. For me it was far too close to the Birdman’s cottage on Heathy Hill. It was Daniel who persuaded me – Daniel had a way with words, he always had.

‘Look, Gracie, if we go up around the back of Samson Hill he won’t see us coming, will he, not if we keep our heads down?’

‘S’pose not,’ I said. ‘But he could if he was looking that way.’

‘So what if he does anyway?’ Daniel went on. ‘We just run away don’t we? He’s an old man, Gracie, the oldest man on the island my Aunty Mildred says. And he limps, so he won’t hardly be able to run after us and catch us, will he?’

‘P’raps not, but . . .’

‘Course he won’t. There’s nothing to be frightened of, Gracie. Anyway we’d have the whole of Rushy Bay to ourselves, nice calm sea and no Big Tim to bother us. No one’s ever going to find us there.’

‘But what if the Birdman does catch us, Daniel? I mean he’s only got to touch us, that’s what I heard.’

‘Who told you that?’

‘Big Tim. He said it was catching. Said the Birdman’s only got to touch you and you’ll catch it. Like measles, he said, like scarlet fever; and it’s not the first time I’ve heard that either.’

‘Catch what?’ Daniel said. ‘What do you mean?’

‘Madness of course. It’s catching, that’s what Big Tim said anyway. Honest, you go loony, just like him if he touches you.’

‘Tommyrot,’ Daniel said. ‘Course you won’t. That’s just Big Tim trying to frighten you. Don’t you know him by now? He’s full of stories, you know that. Honest, Gracie, you won’t go mad or loony or anything else, I swear you won’t. ’S not true anyway, and even if it was true he isn’t going to get near enough to touch us, is he? Oh come on, Gracie, Rushy Bay’s the only place left for us. We’ll keep right to the far end of it, away from his cottage, so that if he does come we can see him coming and then we just run for it. All right?’

‘What would Father say?’ I asked weakly.

‘Nothing, not if he doesn’t know. And he won’t, ’less you tell him of course. You wouldn’t go and tell him would you?’

‘Course not,’ I said.

‘Well that’s all right then isn’t it? Go tomorrow shall we?’

‘S’pose so,’ I said. But I was still not happy about it.

So we went the next day to Rushy Bay to sail our two fastest boats, Shag and Turnstone. It was a Sunday morning after church, I know that because I remember crouching in my pew beside mother that morning and asking God to protect me against the evil powers of the Birdman. When it came to the last words of the Our Father, ‘And deliver us from Evil, Amen’, I squeezed my eyes tight shut and prayed harder than ever before in my life.

As we crawled up through the heather on Samson Hill that morning I tried to turn back, but Daniel would not let me. He took my hand, smiled his sideways smile at me and said I would be all right because he was there and he would look after me. With Daniel and God on my side, I thought, my best friend on earth and my best friend in Heaven, surely nothing could go wrong. I was still trying to convince myself of this when we came over Samson Hill and saw the sand of Rushy Bay below us.

It was deserted just as Daniel had promised. We could see the smoke rising from the two chimneys at either end of the Birdman’s cottage and his two brown goats browsing in the heather beyond, but there was no sign of him anywhere. We sailed Shag and Turnstone until lunchtime. The wind was just right, blowing gently from east to west so that the boats fairly flew over the sea side by side. Turnstone was just that much faster – she always was – and I was worrying now only about the rigging on Shag which had somehow worked itself loose. I had already forgotten all about the Birdman.

When we went back for lunch we hid the boats in amongst the dunes; it would save us carrying them all the way home and all the way back again after lunch. But that afternoon when we returned to the spot we had left them, they were nowhere to be found. At first we thought we might both have been mistaken, that perhaps we had forgotten the exact place we had left them; but the more we searched the surer we were that they were gone and that someone must have taken them. I knew well enough who that someone must be.

I turned for home, calling to Daniel begging him to come with me. He was standing with his back to me on the top of the dunes, hands on hips, his shirt flapping around him, when suddenly he cried out and launched himself down over the dunes and out of sight. My mouth was dry with fear and I had a horrible dread in the pit of my stomach. But curiosity got the better of my fear and I followed him, even though he was running along the beach towards Heathy Hill, towards the Birdman’s Cottage. All the while I called to him to come back, but he would not.

By the time I caught up with him he was crouching down on the sand just below the line of orange and yellow shells left by the high water. There were three boats lying at his feet in the soft white sand. I recognised them at once. There was Shag, Turnstone and beside them, Cormorant. Below them I could see two letters written out in orange shells: Z.W.

We both looked up expecting to see the Birdman standing over us, but there was no one. Smoke still rose from the chimneys in his cottage. The gulls ranged along the ridge of his thatch screeched at us unpleasantly. Then from the dunes close behind us a donkey brayed suddenly and noisily. That was enough even for Daniel. We picked up the boats and we ran; we did not stop running until we had reached the safety of Daniel’s boatshed.

2 Island of Ghosts

TEA WHEN I WAS A CHILD WAS ALWAYS FISH, FISH and potatoes; and that evening it was mullet, a great pink fish that stared up at me with glazed eyes from the platter. I had no appetite for it. All I could think of were those two letters in the sand on Rushy Bay. I had to know one way or the other – I had to be sure it was the Birdman.

I forced myself to eat the fish for I knew mother and father would suspect something if I did not, for mullet was known to be my favourite fish. We ate in silence, busying ourselves over the fish, so I had the whole meal to work out how best to ask them about the initials in the sand, without incriminating myself.

‘Saw the Birdman today,’ I said at last, as casually as I could.

‘Hope you kept your distance,’ said Father, pushing his plate away. ‘With young Daniel Pender again were you? Always with him aren’t you?’ And it was true I suppose. Daniel Pender and Gracie Jenkins were a pair, inseparable. We always had been. He lived just across the way from our front gate at Veronica Farm. Whatever we did, we did together. Father went on. ‘Proper young scallywag his father says he is and I can believe it. You be sure he doesn’t lead you into any trouble, my girl. Always looks like a big puppy that one with his arms and legs too long for the rest of him. Hair’s always stood up on his head like he’s just got out of bed. Proper scallywag he looks.’

‘Looks aren’t everything,’ said mother quietly; and then she smiled and added, ‘they can’t be, can they, else how would I ever have come to pick you?’

‘My beard, perhaps, Clemmie,’ father laughed, and he stroked his beard and smoothed his moustache. He always called her ‘Clemmie’ when he was happy. It was ‘Clem’ when he was angry.

‘You leave Daniel be,’ said Mother. ‘He’s a clever boy, clever with his hands. You seen those boats he makes?’

‘I help him,’ I insisted. ‘I paint them and I make the sails.’

‘Been sailing them all day, I suppose,’ said father. ‘Out by the pool were you? That where you saw the Birdman?’

‘Yes, Father,’ I said; and then, ‘About the Birdman, Father; everyone just calls him “The Birdman”, but he must have a real name like other people, mustn’t he?’

‘Woodcock,’ said father, sitting back in his chair and undoing a notch in his belt as he always did after a meal. ‘Woodcock, that’s what his mother was called anyway. You can see for yourself if you like – she’s buried down in the churchyard somewhere. Last one to leave Samson they say she was, her and the boy. Starving they were by all accounts. Anyway, they came over to Bryher and built that cottage up there on Heathy Hill away from everyone else. The old woman died a few years after I was born. Must have been dead, oh thirty years or more now. The Birdman’s lived on his own up there ever since. But you hear all sorts of things about his old mother. There’s some will tell you she was a witch, and some say she was just plain mad. P’raps she was both, I don’t know. Same with the Birdman; I don’t know whether he’s just mad or evil with it. Either way it’s best to keep away from him. There’s things I could tell you . . .’

‘Don’t go frightening her now with your stories,’ said Mother. ‘Anyway it’s only rumours and tittle-tattle. I don’t believe half of it. If anything goes wrong on this island they blame it on the Birdman. Lobsters aren’t there to be caught – it’s his fault. Blight in the potatoes – it’s his fault. Anyone catches the fever – it’s his fault. Dog goes missing – they say he’s eaten it. Lot of old nonsense. He’s just a bit simple, bit mad perhaps, that’s all.’

‘Simple my aunt,’ Father said, getting up and going over to his chair by the stove. ‘And what’s more, it’s not all tittle-tattle, Clemmie, not all of it. You know it’s not.’

‘There’s no need to tell her any more,’ said Mother. ‘Long as she doesn’t go anywhere near him, long as she keeps off Samson, that’s all that matters. Don’t you go filling her head with all those stories.’

‘But they’re not all stories, are they, Clemmie? Remember what happened to Charlie Webber?’

‘Charlie Webber? Who’s he?’ I asked.

‘Never you mind about Charlie Webber,’ said Mother; and she spoke firmly to Father.

‘That’s enough – you’ll only frighten her.’

But Father ignored her. He leaned forward towards me in his chair, stuffing his pipe with tobacco. ‘Charlie Webber was my best friend when I was a boy, Gracie. Got into all sorts of scrapes and capers together, Charlie and me. Nothing we wouldn’t tell each other; and Charlie wouldn’t ever have lied to me, not in a million years. He wasn’t like that, was he, Clemmie?’ But Mother wouldn’t answer him. She walked away and busied herself at the sink. His voice dropped to a whisper now, almost as if he was afraid of being overheard. ‘There’s always been strange stories about Samson, Gracie. Course, people only half-believed them, but they’ve always steered clear of Samson all the same, just in case. But it was all on account of the Birdman and his mother that Samson became a place no one dared go near. They were the ones who put it about that there was a curse on the place. They were always warning everyone to keep off, so we did. They told everyone it was an island of ghosts, that whoever set foot on the place would bring the terrible curse of Samson down on his family. No one quite believed all that about ghosts and curses; but just the same everyone kept well clear of the place, everyone except Charlie.’

Father lit up his pipe and sat back in his chair which creaked underneath him as it always did whenever he moved. ‘I never went over there, but Charlie did. It was a day I’ll never forget, never, never – low tide, no water to speak of between Bryher and Samson. You could walk across. It was my idea, and not one I’m proud of, Gracie, I can tell you. It was me that dared Charlie Webber. I dared him to walk over to Samson. We were always daring each other to do silly things, that’s just how we were; and Charlie Webber never could resist a dare. I stood on top of Samson Hill, and watched him running over the sands towards Samson, leaping the pools. It took him about ten minutes I suppose and there he was jumping up and down on the beach waving and shouting to me, when suddenly this man in a black sou’wester appeared out of the dunes behind him, came from nowhere. He began screaming at Charlie like some mad fiend and Charlie ran and ran and ran. He ran like a hare all the way back across the sand, stumbling and splashing through the shallows. By the time he reached me he was white with fear, Gracie, white with it I tell you. But that’s not all of it. That very same night Charlie Webber’s house was burnt to the ground. It’s true, Gracie. Everyone managed to get out alive, but they never did find out what caused the fire; but Charlie knew all right, and I knew. Next day Charlie went down with the scarlet fever. I caught it after him and then near enough every child on the island got it. Aunty Mildred – you know Daniel’s Aunty Mildred – she was just a baby at the time and she nearly died of it.’

‘Did Charlie Webber die of it?’ I asked.

‘Now that’s enough,’ said Mother sharply. ‘You’ve said enough.’

‘Clem,’ said Father, ‘she’s ten years old and she’s not a baby any more. She’s old enough to hear the rest of it.’ He lit his pipe again, drawing on it deeply several times before he shook out the match. ‘No, Gracie, Charlie didn’t die, but he had to leave the island. His family was ruined, couldn’t afford to rebuild the house. But before Charlie left for good he told me something I’ll never forget. The day after the fire, Charlie was sitting on the quay when he felt someone behind him. He looked around and there was the Birdman. There was nowhere for Charlie to run to. He’d come, he said, to say sorry to Charlie, to explain to him that it wasn’t his fault. There was nothing he could do once Charlie had set foot on Samson. He told Charlie that there was a curse on the island, that the ghosts of the dead haunted the place and could not rest, not until the guilt of Samson had been redeemed, whatever that meant. And when Charlie asked him why there was a curse on Samson, why the ghosts could not rest – this is what he told him. He was a little boy when it happened, younger than Charlie, he said. The people of Samson woke up one morning to find a ship run aground on a sandbank off Samson. Like a ghost ship it was on a flat calm sea. No fog, no wind, no reason for it to be there. They rowed out and hailed it, but no one answered; so they clambered on board. There was no one there. The ship was deserted. Well you don’t look a gift horse in the mouth, do you? Every man on Samson, sixteen of them there were in all he said – every one of them was on that ship when it refloated at high tide. They sailed it off to Penzance to claim the salvage money, but they never got there. The ship foundered on the Wolf Rock, off Land’s End, went down in broad daylight, mind you; gentle breeze, no fog. Every man on board was lost. The Birdman’s own father went down on that ship, Gracie.’

‘It’s a horrible story,’ said Mother, ‘horrible. Every time I hear it it makes me shiver.’

‘True nonetheless, Clemmie,’ father said. ‘And that wasn’t the last of it. It seems things went from bad to worse on Samson after that. With no men left to go fishing or to work up the fields, the women and children soon began to go hungry. All they had to eat was limpets. The Birdman told Charlie that they even had to eat the dogs. It’s true, Gracie, that’s what Charlie told me. Then with the hunger came the fever, and the old folk and the babies began to die. So they left. One by one the families left the island until the Birdman and his mother were alone on Samson.’