Полная версия

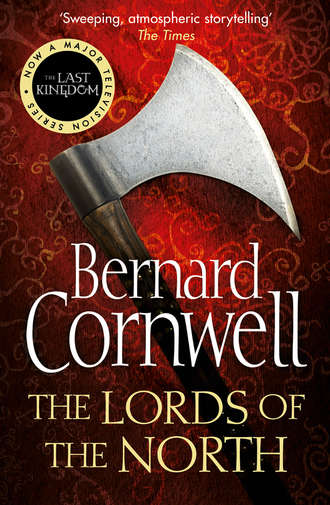

The Lords of the North

Sven still did not move as I stooped to his belt and pulled away a heavy purse. Then I stripped him of his seven silver arm rings. Hild had cut off part of Gelgill’s robe and was using it to make a bag to hold the coins in the slave-trader’s tray. I gave her my father’s helmet to carry, then climbed back into Witnere’s saddle. I patted his neck and he tossed his head extravagantly as though he understood he had been a great fighting stallion that day.

I was about to leave when that weird day became stranger still. Some of the captives, as if realising that they were truly freed, had started towards the bridge, while others were so confused or lost or despairing that they had followed the armed men eastwards. Then, suddenly, there was a monkish chanting and out of one of the low, turf-roofed houses where they had been imprisoned, came a file of monks and priests. There were seven of them, and they were the luckiest men that day, for I was to discover that Kjartan the Cruel did indeed have a hatred of Christians and killed every priest or monk he captured. These seven escaped him now, and with them was a young man burdened with slave shackles. He was tall, well-built, very good-looking, dressed in rags and about my age. His long curly hair was so golden that it looked almost white and he had pale eyelashes and very blue eyes and a sun-darkened skin unmarked by disease. His face might have been carved from stone, so pronounced were his cheekbones, nose and jaw, yet the hardness of the face was softened by a cheerful expression that suggested he found life a constant surprise and a continual amusement. When he saw Sven cowering beneath my horse he left the chanting priests and ran towards us, stopping only to pick up the sword of the man I had killed. The young man held the sword awkwardly, for his hands were joined by links of chain, but he carried it to Sven and held it poised over Sven’s neck.

‘No,’ I said.

‘No?’ The young man smiled up at me and I instinctively liked him. His face was open and guileless.

‘I promised him his life,’ I said.

The young man thought about that for a heartbeat. ‘You did,’ he said, ‘but I didn’t.’ He spoke in Danish.

‘But if you take his life,’ I said, ‘then I shall have to take yours.’

He considered that bargain with amusement in his eyes. ‘Why?’ he asked, not in any alarm, but as if he genuinely wished to know.

‘Because that is the law,’ I said.

‘But Sven Kjartanson knows no law,’ he pointed out.

‘It is my law,’ I said, ‘and I want him to take a message to his father.’

‘What message?’

‘That the dead swordsman has come for him.’

The young man cocked his head thoughtfully as he considered the message and he evidently approved of it for he tucked the sword under an armpit and then clumsily untied the rope belt of his breeches. ‘You can take a message from me too,’ he said to Sven, ‘and this is it.’ He pissed on Sven. ‘I baptise you,’ the young man said, ‘in the name of Thor and of Odin and of Loki.’

The seven churchmen, three monks and four priests, solemnly watched the baptism, but none protested the implied blasphemy or tried to stop it. The young man pissed for a long time, aiming his stream so that it thoroughly soaked Sven’s hair, and when at last he finished he retied the belt and offered me another of his dazzling smiles. ‘You’re the dead swordsman?’

‘I am,’ I said.

‘Stop whimpering,’ the young man said to Sven, then smiled up at me again. ‘Then perhaps you will do me the honour of serving me?’

‘Serve you?’ I asked. It was my turn to be amused.

‘I am Guthred,’ he said, as though that explained everything.

‘Guthrum I have heard of,’ I said, ‘and I know a Guthwere and I have met two men named Guthlac, but I know of no Guthred.’

‘I am Guthred, son of Hardicnut,’ he said.

The name still meant nothing to me. ‘And why should I serve Guthred,’ I asked, ‘son of Hardicnut?’

‘Because until you came I was a slave,’ he said, ‘but now, well, because you came, now I’m a king!’ He spoke with such enthusiasm that he had trouble making the words come out as he wanted.

I smiled beneath the linen scarf. ‘You’re a king,’ I said, ‘but of what?’

‘Northumbria, of course,’ he said brightly.

‘He is, lord, he is,’ one of the priests said earnestly.

And so the dead swordsman met the slave king, and Sven the One-Eyed crawled to his father, and the weirdness that infected Northumbria grew weirder still.

Two

At sea, sometimes, if you take a ship too far from land and the wind rises and the tide sucks with a venomous force and the waves splinter white above the shield-pegs, you have no choice but to go where the gods will. The sail must be furled before it rips and the long oars would pull to no effect and so you lash the blades and bail the ship and say your prayers and watch the darkening sky and listen to the wind howl and suffer the rain’s sting, and you hope that the tide and waves and wind will not drive you onto rocks.

That was how I felt in Northumbria. I had escaped Hrothweard’s madness in Eoferwic, only to humiliate Sven who would now want nothing more than to kill me, if indeed he believed I could be killed. That meant I dared not stay in that middling part of Northumbria for my enemies in the region were far too numerous, nor could I go farther north for that would take me into Bebbanburg’s territory, my own land, where it was my uncle’s daily prayer that I should die and so leave him the legitimate holder of what he had stolen, and I did not wish to make it easy for that prayer to come true. So the winds of Kjartan’s hatred and of Sven’s revenge, and the tidal thrust of my uncle’s enmity drove me westwards into the wilds of Cumbraland.

We followed the Roman wall where it runs across the hills. That wall is an extraordinary thing which crosses the whole land from sea to sea. It is made of stone and it rises and falls with the hills and the valleys, never stopping, always remorseless and brutal. We met a shepherd who had not heard of the Romans and he told us that giants had built the wall in the old days and he claimed that when the world ends the wild men of the far north would flow across its rampart like a flood to bring death and horror. I thought of his prophecy that afternoon as I watched a she-wolf run along the wall’s top, tongue lolling, and she gave us a glance, leaped down behind our horses and ran off southwards. These days the wall’s masonry has crumbled, flowers blossom between the stones and turf lies thick along the rampart’s wide top, but it is still an astonishing thing. We build a few churches and monasteries of stone, and I have seen a handful of stone-built halls, but I cannot imagine any man making such a wall today. And it was not just a wall. Beside it was a wide ditch, and behind that a stone road, and every mile or so there was a watchtower, and twice a day we would pass stone-built fortresses where the Roman soldiers had lived. The roofs of their barracks have long gone now and the buildings are homes for foxes and ravens, though in one such fort we discovered a naked man with hair down to his waist. He was ancient, claiming to be over seventy years old, and his grey beard was as long as his matted white hair. He was a filthy creature, nothing but skin, dirt and bones, but Willibald and the seven churchmen I had released from Sven all knelt to him because he was a famous hermit.

‘He was a bishop,’ Willibald told me in awed tones after he had received the scraggy man’s blessing. ‘He had wealth, a wife, servants and honour, and he gave them all up to worship God in solitude. He’s a very holy man.’

‘Perhaps he’s just a mad bastard,’ I suggested, ‘or else his wife was a vicious bitch who drove him out.’

‘He’s a child of God,’ Willibald said reprovingly, ‘and in time he’ll be called a saint.’

Hild had dismounted and she looked at me as though seeking my permission to approach the hermit. She plainly wanted the hermit’s blessing and so she appealed to me, but it was none of my business what she did, so I just shrugged and she knelt to the dirty creature. He leered at her and scratched his crotch and then made the sign of the cross on both her breasts, pushing hard with his fingers to feel her nipples and all the while pretending to bless her, and I was tempted to kick the old bastard into immediate martyrdom. But Hild was crying with emotion as he pawed at her hair and then dribbled some kind of prayer and afterwards she looked grateful. He gave me the evil eye and held out a grubby paw as if expecting me to give him money, but instead I showed him Thor’s hammer and he hissed a curse at me through his two yellow teeth and then we abandoned him to the moor and to the sky and to his prayers.

I had left Bolti. He was safe enough north of the wall, for he had entered Bebbanburg’s territory where Ælfric’s horsemen and the horsemen of the Danes who lived on my land would be patrolling the roads. We followed the wall westwards and I now led Father Willibald, Hild, King Guthred and the seven freed churchmen. I had managed to break the chain of Guthred’s manacles so the slave king, who now rode Willibald’s mare, wore two iron wristbands from which dangled short links of rusted chain. He chattered to me incessantly. ‘What we shall do,’ he told me on the second day of the journey, ‘is raise an army in Cumbraland and then we’ll cross the hills and capture Eoferwic.’

‘What then?’ I asked drily.

‘Go north!’ he said enthusiastically. ‘North! We shall have to take Dunholm, and after that we’ll capture Bebbanburg. You want me to do that, don’t you?’

I had told Guthred my name and that I was the rightful lord of Bebbanburg, and now I told him that Bebbanburg had never been captured.

‘It’s a tough place, eh?’ Guthred responded. ‘Like Dunholm? Well, we shall see about Bebbanburg. But of course we’ll have to finish off Ivarr first.’ He spoke as though destroying the most powerful Dane in Northumbria were a small matter. ‘So we’ll deal with Ivarr,’ he said, then suddenly brightened. ‘Or perhaps Ivarr will accept me as king? He has a son and I’ve a sister who must be of marriageable age by now. They could make an alliance?’

‘Unless your sister’s already married,’ I interrupted.

‘Can’t think who’d want her,’ he said, ‘she’s got a face like a horse.’

‘Horse-faced or not,’ I said, ‘she’s Hardicnut’s daughter. There must be an advantage for someone in marrying her.’

‘There might have been before my father died,’ Guthred said dubiously, ‘but now?’

‘You’re king now,’ I reminded him. I did not really believe he was a king, of course, but he believed it and so I indulged him.

‘That’s true!’ he said. ‘So someone will want Gisela, won’t they? Despite her face!’

‘Does she really look like a horse?’

‘Long face,’ he said, and grimaced, ‘but she’s not completely ugly. And it’s high time she married. She must be fifteen or sixteen! I think perhaps we should marry her to Ivarr’s son. That’ll make an alliance with Ivarr, and he’ll help us deal with Kjartan, and then we’ll have to make sure the Scots don’t give us any trouble. And, of course, we’ll have to keep those rascals in Strath Clota from being a nuisance.’

‘Of course we must,’ I said.

‘They killed my father, see? And made me a slave!’ He grinned.

Hardicnut, Guthred’s father, had been a Danish earl who made his home at Cair Ligualid which was the chief town in Cumbraland. Hardicnut had called himself king of Northumbria, which was pretentious, but strange things happen west of the hills and a man there can claim to be king of the moon if he wants because no one outside of Cumbraland will take the slightest bit of notice. Hardicnut had posed no threat to the greater lords around Eoferwic, indeed he posed small threat to anyone, for Cumbraland was a sad and savage place, forever being raided by the Norsemen from Ireland or by the wild horrors from Strath Clota whose king, Eochaid, called himself king of Scotland, a title disputed by Aed who was now fighting Ivarr.

Of the insolence of the Scots, my father used to say, there is no end. He had cause to say that, for the Scots claimed much of Bebbanburg’s land and until the Danes came our family was forever fighting against the northern tribes. I had been taught as a child that there were many tribes in Scotland, but the two tribes closest to Northumbria were the Scots themselves, of whom Aed was now king, and the savages of Strath Clota who lived on the western shore and never came near Bebbanburg. They raided Cumbraland instead and Hardicnut had decided to punish them and so led a small army north into their hills where Eochaid of Strath Clota ambushed him and then destroyed him. Guthred had marched with his father and had been captured and, for two years now, had been a slave.

‘Why didn’t they kill you?’ I asked.

‘Eochaid should have killed me,’ he admitted cheerfully, ‘but he didn’t know who I was at first, and by the time he found out he wasn’t really in a killing mood. So he kicked me a few times, then said I would be his slave. He liked to watch me empty his shit-pail. I was a household slave, see? It was another insult.’

‘Being a household slave?’

‘Woman’s work,’ Guthred explained, ‘but that meant I spent my time with the girls. I rather liked it.’

‘So how did you escape Eochaid?’

‘I didn’t. Gelgill bought me. He paid a lot for me!’ He said this proudly.

‘And Gelgill was going to sell you to Kjartan?’ I asked.

‘Oh no! He was going to sell me to the priests from Cair Ligualid!’ he nodded towards the seven churchmen who had been rescued with him. ‘They’d agreed the price before, you see, but Gelgill wanted more money and then they all met Sven, and of course Sven wouldn’t let the sale happen. He wanted me back in Dunholm and Gelgill would have done anything for Sven and his father, so we were all doomed until you came along.’

Some of this made sense and, by talking to the seven churchmen and questioning Guthred further, I managed to piece the rest of the story together. Gelgill, known on both sides of the border as a slave-trader, had purchased Guthred from Eochaid and had paid a vast price, not because Guthred was worth it, but because the priests had hired Gelgill to make the trade. ‘Two hundred pieces of silver, eight bullocks, two sacks of malt and a silver-mounted horn. That was my price,’ Guthred told me cheerfully.

‘Gelgill paid that much?’ I was astonished.

‘He didn’t. The priests did. Gelgill just negotiated the sale.’

‘The priests paid for you?’

‘They must have emptied Cumbraland of silver,’ Guthred said proudly.

‘And Eochaid agreed to sell you?’

‘For that price? Of course he did! Why wouldn’t he?’

‘He killed your father. Your duty is to kill him. He knows that.’

‘He rather liked me,’ Guthred said, and I found that believable because Guthred was so very likeable. He faced each day as though it would bring nothing but happiness, and in his company life somehow seemed brighter. ‘He still made me empty his shit-pail,’ Guthred admitted, continuing his story of Eochaid, ‘but he stopped kicking me every time I did it. And he liked to talk to me.’

‘About what?’

‘Oh, about everything! The gods, the weather, fishing, how to make good cheese, women, everything. And he reckoned I wasn’t a warrior, which I’m not really. Now I’m king, of course, so I have to be a warrior, but I don’t much like it. Eochaid made me swear I’d never go to war against him.’

‘And you swore that?’

‘Of course! I like him. I’ll raid his cattle, of course, and kill any men he sends into Cumbraland, but that’s not war, is it?’

So Eochaid had taken the church’s silver and Gelgill had brought Guthred south into Northumbria, but instead of giving him to the priests he had taken him eastwards, reckoning that he could make more money by selling Guthred to Kjartan than by honouring the contract he had made with the churchmen. The priests and monks followed, begging for Guthred’s release, and it was then they had all met Sven who saw his own chance of profit in Guthred. The freed slave was Hardicnut’s son, which meant he was heir to land in Cumbraland, and that suggested he was worth a largish bag of silver in ransom. Sven had planned to take Guthred back to Dunholm where he would doubtless have killed all seven churchmen. Then I had arrived with my face wrapped in black linen and now Gelgill was dead, Sven had stinking wet hair and Guthred was free.

I understood all that, but what did not make sense was why seven Saxon churchmen had come from Cair Ligualid to pay a fortune for Guthred who was both a Dane and a pagan. ‘Because I’m their king, of course,’ Guthred said, as though the answer were obvious, ‘though I never thought I’d become king. Not after Eochaid took me captive, but that’s what the Christian god wants, so who am I to argue?’

‘Their god wants you?’ I asked, looking at the seven churchmen who had travelled so far to free him.

‘Their god wants me,’ Guthred said seriously, ‘because I’m the chosen one. Do you think I should become a Christian?’

‘No,’ I said.

‘I think I should,’ he said, ignoring my answer, ‘just to show gratitude. The gods don’t like ingratitude, do they?’

‘What the gods like,’ I said, ‘is chaos.’

The gods were happy.

Cair Ligualid was a sorry place. Norsemen had pillaged and burned it two years before, just after Guthred’s father had been killed by the Scots, and the town had not even been half rebuilt. What was left of it stood on the south bank of the River Hedene, and that was why the settlement existed, for it was built at the first crossing place of the river, a river which offered some protection against marauding Scots. It had offered no protection against the fleet of Vikings who had sailed up the Hedene, stolen whatever they could, raped what they wanted, killed what they did not want, and taken away the survivors as slaves. Those Vikings had come from their settlements in Ireland and they were the enemies of the Saxons, the Irish, the Scots and even, at times, of their cousins, the Danes, and they had not spared the Danes living in Cair Ligualid. So we rode through a broken gate in a broken wall into a broken town, and it was dusk, and the day’s rain had finally lifted and a shaft of red sunlight came from beneath the western clouds as we entered the ruined town. We rode straight into the light of that swollen sun which reflected from my helm that had the silver wolf on its crest and it shone from my mail coat and from my arm rings and from the hilts of my two swords, and someone shouted that I was the king. I looked like a king. I rode Witnere who tossed his great head and pawed at the ground and I was dressed in my shining war-glory.

Cair Ligualid was crowded. Here and there a house had been rebuilt, but most of the folk were camping in the scorched ruins, along with their livestock, and there were far too many of them to be the survivors of the old Norse raids. They were, instead, the people of Cumbraland who had been brought to Cair Ligualid by their priests or lords because they had been promised that their new king would come. And now, from the east, his mail reflecting the brilliance of the sinking sun, came a gleaming warrior on a great black horse.

‘The king!’ another voice shouted, and more voices took up the cry, and from the wrecked homes and the makeshift shelters folk scrambled to stare at me. Willibald was trying to hush them, but his West Saxon words were lost in the din. I thought Guthred would also protest, but instead he pulled his cloak’s hood over his head so that he looked like one of the churchmen who struggled to keep up as the crowd pressed in on us. Folk knelt as we passed, then scrambled to their feet to follow us. Hild was laughing, and I took her hand so she rode beside me like a queen, and the growing crowd accompanied us up a long, low hill towards a new hall built on the summit. As we grew closer I saw it was not a hall, but a church, and that priests and monks were coming from its door to greet us.

There was a madness in Cair Ligualid. A different madness from that which had shed blood in Eoferwic, but madness just the same. Women were crying, men shouting and children staring. Mothers held babies towards me as if my touch could heal them. ‘You must stop them!’ Willibald had managed to reach my side and was clinging onto my right stirrup.

‘Why?’

‘Because they’re mistaken, of course! Guthred is king!’

I smiled at him. ‘Maybe,’ I said slowly, as though the idea were just coming to me, ‘maybe I should be king instead?’

‘Uhtred!’ Willibald said, shocked.

‘Why not?’ I asked. ‘My ancestors were kings.’

‘Guthred is king!’ Willibald protested. ‘The abbot named him!’

That was how Cair Ligualid’s madness began. The town had been a haunt of foxes and birds when Abbot Eadred of Lindisfarena came across the hills. Lindisfarena, of course, is the monastery hard by Bebbanburg. It lies on Northumbria’s eastern coast, while Cair Ligualid is on the western edge, but the abbot, driven from Lindisfarena by Danish raids, had come to Cair Ligualid and there built the new church to which we climbed. The abbot had also seen Guthred in his dreams. Nowadays, of course, every Northumbrian knows the story of how Saint Cuthbert revealed Guthred to Abbot Eadred, but back then, on the day of Guthred’s arrival in Cair Ligualid, the tale seemed like just another insanity on top of the world’s weltering madness. Folk were shouting at me, calling me king and Willibald turned and bellowed to Guthred. ‘Tell them to stop!’

‘The people want a king,’ Guthred said, ‘and Uhtred looks like one. Let them have him for the moment.’

A number of younger monks, armed with staves, kept the excited people away from the church doors. The crowd had been promised a miracle by Eadred and they had been waiting for days, expecting their king to come, and then I had ridden from the east in the glory of a warrior, which is what I am and always have been. All my life I have followed the path of the sword. Given a choice, and I have been given many choices, I would rather draw a blade than settle an argument with words, for that is what a warrior does, but most men and women are not fighters. They crave peace. They want nothing more than to watch their children grow, to plant their seeds and live to see the harvest, to worship their god, to love their family and to be left in peace. Yet it has been our fate to be born in a time when violence ruled us. The Danes appeared and our land was shattered, and all around our coasts the long ships with their beaked prows came to raid and enslave and steal and kill. In Cumbraland, which is the wildest part of all the Saxon lands, the Danes came and the Norsemen came and the Scots came, and no one could live in peace, and I think that when you break men’s dreams, when you destroy their homes and ruin their harvests and rape their daughters and enslave their sons, you engender a madness. At the world’s ending, when the gods will fight each other, all mankind will be stricken with a great frenzy and the rivers will flow with blood and the sky shall be filled with screaming and the great tree of life will fall with a crash that will be heard beyond the farthest star, but all that is yet to come. Back then, in 878 when I was young, there was just a smaller madness at Cair Ligualid. It was the madness of hope, the belief that a king, born in a churchman’s dream, would end a people’s suffering.

Abbot Eadred was waiting inside the cordon of monks and, as my horse came close, he raised his hands towards the sky. He was a tall man, old and white-haired, gaunt and fierce, with eyes like a falcon and, surprising in a priest, he had a sword strapped to his waist. He could not see my face at first because my cheek-pieces hid it, but even when I took off my helmet he still thought I was the king. He stared up at me, raised thin hands to heaven as if giving thanks for my arrival, then gave me a low bow. ‘Lord King,’ he said in a booming voice. The monks dropped to their knees and stared up at me. ‘Lord King,’ Abbot Eadred boomed again, ‘welcome!’