Полная версия

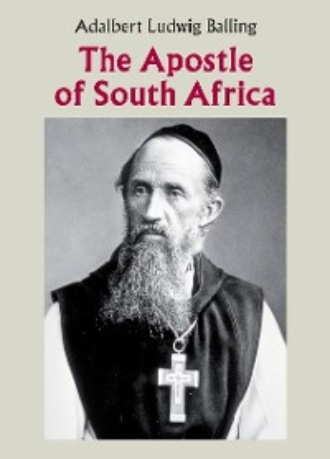

The Apostle of South Africa

The number of monks, recruited for the most part by either Fr. Franz himself or his tireless travelling Brother Zacharias, increased steadily. After ten years, Mariastern counted seventy priests and Brothers!

Mariastern was known for its charity towards the poor.

Abbot Francis:

“I organized a collection of second-hand liturgical vestments in Austria and made sure that they were repaired before they were distributed to the poorest churches in Bosnia. However, what are a few vestments for so many? – In the sacristies of Rome many old vestments are eaten by moths. Many things are discarded simply because they are old and worn. If I could have these as a donation, I would be as content as poor Lazarus was with the crumbs falling from the rich man’s table. A committee of generous helpers could be organized to save these things from complete decay. I am not asking for nice things but will be more than content with old chasubles and other vestments of little value.

I offer to pay for repair and transport. I would be very glad if my suggestion was taken up and I could make my poor Bosnians happy. God will abundantly reward anyone who contributes to this work of mercy.”

Another charity Fr. Franz undertook was a Christian school at Banjaluka. He won the Mercy Sisters of Agram to run it by assuring them of all possible assistance. He would not only obtain a suitable site for them but also provide furniture and teaching aids. When later he helped the Sisters to clear their debts, he did so as usual: by approaching his German friends and benefactors to make a contribution to a worthy cause. One of his biographers wrote of him:

“Fr. Franz must be credited with selflessly and disinterestedly having established the first Catholic School in Banjaluka. He wanted poor people to come in touch with the rest of the world and also give them a better understanding of the Christian faith.”. (Timotheus Kempf CMM)

Bosnian Customs and Traditions

When in 1874 Mariastern’s pater immediatus, Abbot Henri of Port du Salut came on visitation, he marveled at what Fr. Francis, who had meanwhile become Prior, and his monks had achieved. He also had high praise for the good work of the Sisters in predominantly Muslim surroundings. Still more surprised he was about the customs and usages of the Bosnian people. As he spoke only French, he was accompanied by an interpreter, Fr. Bonaventure Bayer who was fluent in German and French. In order to give his French visitors a taste of the real Bosnia, Fr. Franz decided to put them through a few experiences. He began by rowing them across the River Sava which at that time formed the border between Slovenia and Bosnia. Once Old Gradiska was behind them, he invited them to make themselves comfortable on a bed of hay, laid out for them on a rack waggon. Their eyes grew bigger by the hour, but they did not say a thing.

Abbot Francis:

“We traveled for about two hours over the rough and the smooth until we came to a coffee house. The innkeeper, barefoot, in an old pair of pants and a tatty shirt which was open all the way to his belly button, thus exposing his sweaty chest, extended a rare welcome to my two visitors, addressing me as Gospodin (Sir). When he brought in the coffee I asked him if perchance he also had cups. He did. Reaching into his shirt, he conjured up an array of dirty tin mugs, put them on the table in front of my visitors and muttered the courteous Isvolite! (s’il vous plait). Next he produced two lumps of sugar from his pocket and, placing the smaller one into my cup, bit the other in two on his foul teeth, to place one half into each of the remaining cups. It was all my pater immediatus could take, crying: ‘Mon Dieu! It’s enough’!”

But he had only had a small glimpse of Bosnia. Abbot Francis adds that the innkeeper was actually “one of the finer specimens of a Greek”, and with regard to courtesy and etiquette certainly superior to most Bosnian and Turkish landlords.

After rumbling along on the rack waggon for two more hours across country the party stopped at another wayside inn to rest and feed the horses. This time, Fr. Franz ordered a Lenten meal consisting of flour, milk and eggs. It was served on a flat dish together with bread but without a knife or fork, table cloth or serviette. Thus he “had the honour” of showing his bewildered visitors how to eat without the cultural accessories they were used to, by demonstrating how the bread could be broken into convenient pieces, dipped one piece at a time into the dish, picked up with some of the egg mix and brought safely to the mouth.

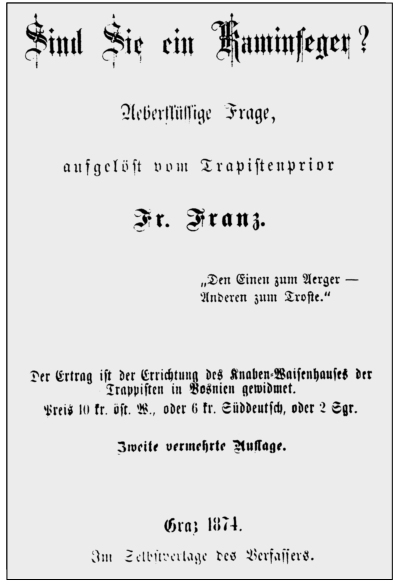

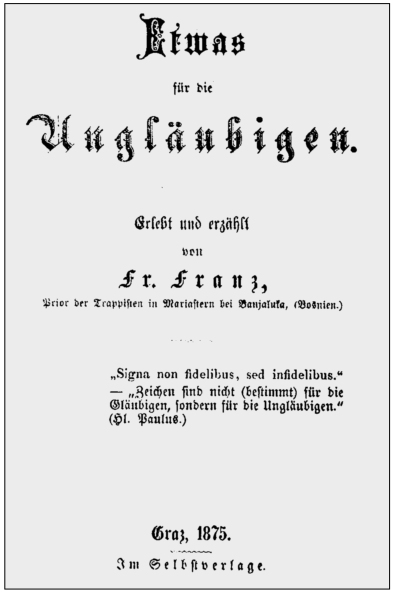

The following illustrations are title covers of two brochures which the Founder published in Bosnia.

The first two unique publications by Fr. Franz.1874 and 1875

The first title reads:

“Are you a Chimney Sweep? – A Redundant Question, annoying to some and comforting to others and answered here by Fr. Francis. – All proceeds towards the establishment of a boys’ orphanage in Banjaluka.

Price: 10 crowns in Austrian or South German currency. –

2nd Enlarged Edition, Graz 1874.

The first two unique publications by Fr. Franz.1874 and 1875

The second title reads: “Something for Unbelievers”. Experienced and narrated by Fr. Francis, Prior of the Trappists of Mariastern near Banjaluka in Bosnia.

Signa non fidelibus, sed infidelibus: “Signs are intended, not for believers but unbelievers”. (St. Paul)

Graz. Author’s Edition.

When the party finally reached the monastery, it was the Prior’s turn to learn a new custom. He could not trust his eyes. Most evidently, “there were Trappists who ate meat while they were not sick”. He found out that a private physician had prescribed meat to his visitors. He was shocked. But hardly had he recovered from the first surprise when he was in for another.

Abbot Francis, in jovial mood:

“I discovered the French cure for obesity. Abbot Henri suffered from this condition but he had found a ‘cure’. His ‘physician’ used to cut a deep hole in his upper arm, place a pea or bean in the wound, bandage it and allow the blood to turn septic. I saw with my own eyes how Fr. Bonaventure, the ‘physician’, took a bean out of such a wound, put in another one and bandaged the arm again. He did so three times a day. Imagine: Instead of prescribing a diet low in blood-builders, he tried to cure his abbot with meat and beans!”

The visitation as such was uneventful. Abbot Henri issued a few general admonitions concerning the novitiate and general cleanliness. He was apparently not able to cope with his responsibilities as abbot. A few years later he was retired and lived out his days on a small pension at a Roman convent: “a way of losing weight without beans”. (Abbot Francis) His companion and interpreter, Fr. Bonaventura Bayer, on the other hand, was transferred to Mariastern, mainly “to foster the good monastic spirit”. The chronicler concludes that the visitation was a benefit for Mariastern: “It strengthened the spirit of harmony and charity between superiors and subjects. Afterwards, Prior Francis was able to turn to his higher superiors for counsel and support whenever he faced internal or external difficulties. He did not need to legitimize himself anymore to those who doubted his monastic loyalty. As a result, he enjoyed greater recognition and honor in church circles, something that is not to be underestimated if a monastery is expected to prosper.”

VII.

Building Projects Completed

Plans for a New Foundation The Seer of Wittelsheim

Though the Pasha of Banjaluka was aware that Prior Francis had a building licence from the Grand Vizier he pretended not to know. Whenever an opportunity presented itself he did everything in his power to outwit him. Fr. Franz, however, was not hoodwinked by a Turk. More often than not he drew a red herring across the Pasha’s track. With his opponent kept at bay, the number of monks and buildings increased. But not everything went smoothly at Mariasterrn. In the spring of 1873 “we lost all our cattle to anthrax”. This was a major disaster and one which taught the Prior a lesson. He made sure it would not be repeated. He asked his brother to “find him some fine Allgau cows and a breed bull.” The animals were transported to the border by rail and from there driven to Banjaluka. Prior Franz: “Once we had a new breed, farmers came for calves, as also did the Pasha, who of course wanted his for free!”

In December 1874, the Prior reviewed Mariastern’s progress for the “Vorarlberger Volkszeitung”:

“Where five years ago there was nothing but wood and the occasional Turkish maize field or a patch of ownerless land, you will now find a monastery and a church though both still need plastering. The two buildings form a quadrangle enclosing a garden. The longest wall measures 130’. (40 m). – The following projects have been completed: a farm house with stables and barns, a flour mill and a saw mill, a large prune drier, a small brewery and several trade shops. At a short distance from the monastery we have a brick yard to make bricks and shingles, and a little further, a quarry from which we get all our stones. We split the rocks with either a pick axe or dynamite. – Two major events this year were the arrival of our new novice master, Fr. Bonaventura Bayer, and the ordination to the priesthood of Fr. Joseph Biegner, who has been with us practically from the beginning. It was Bishop Josip Juraj Strossmayer who at the cathedral of Djakovo in Slavonia conferred Holy Orders on him.”

As early as September 1874, Prior Francis presented a plan for a second Trappist monastery in Bosnia to the general chapter at Sept-Fons. The name he had chosen for it was “Mariannaberg”. But before he could begin with the construction there were obstacles to overcome. One was the Franciscans. To his greatest surprise he discovered that the bishop, also a Franciscan, was making common cause with the Pasha to obstruct Mariastern’s further development. Despite the fact that the bishop had been the first one to support his plan for expansion and despite the repeated requests by the surrounding Catholics for pastoral assistance, Vuicic turned against the Trappists. His opposition went as far as “not to allow our priests to hear Confession except of fellow monks”.

Visit to the Seers of Wittelsheim

In 1874, Prior Francis was late for the annual general chapter at Sept-Fons. This was due partly to poor train connections but partly also to his own scheduling. On their way to France he and Br. Zacharias stopped at Wittelsheim in the Alsace to meet “the seers”. In a brochure entitled “Something for Unbelievers”. (Graz, 1874) he tells us that he was driven mainly by curiosity. He wanted to know if the visionaries and their visions were as trustworthy as they were given out to be. If so then one or the other might tell him whether God wanted a second monastery in Bosnia or not. They began their inquiries by calling on the parish priest at Krueth. He gave them what information he had about the seers – twenty altogether. After that they went straight to Wittelsheim, where most of them lived. Stopping over at the “The Stork”. (inn) they were told by the innkeeper’s wife that three of the seers, including a Mrs. Maria Schott, were probably more reliable than the others. So they got in touch with Mrs. Schott without, however, telling her who they were. It was agreed that they meet the following morning after Mass.

Prior Francis:

“Mrs. Schott told us what she had seen during Mass: ‘I saw Our Lady standing on the main altar and on her side, St. Joseph and the Holy Father, the latter looking quite depressed.’

In another vision she described the Prior’s late parents “so accurately and detailed” that he could not have done better. Her words imprinted themselves on his memory. This is what he wrote in old age:

“Mrs. Schott knew nothing about me and even less about my relatives. How could she know that I came from Turkey to test the truth of her visions? I had been careful not to tell the innkeeper who we were. Even the villagers did not know what to make of me on account of my red beard and long red coat. But at a certain point, when I began to be convinced about the seer’s integrity and the genuineness of her visions, I introduced myself to her. Even so, I did not stop questioning her, just to make sure that I was not deceived. I asked her: ‘What do you see about my deceased Brothers in the monastery?’ She answered without a moment’s hesitation: ‘I see two Brothers dressed in brown like the Brother next to you; one appears golden, the other is still dark.’ I asked myself: How can this ordinary woman know that we have already lost two Brothers to death?”

When on the following day the Prior celebrated Mass, Mrs. Schott attended. Afterwards he and Br. Zacharias asked her more questions and understood from her answers that she had actually seen some of their deceased relatives. Much emboldened, the Prior asked her what she saw about their monastery. “I see Our Lady”, she replied, “and, look, she is blessing you with a star in her hand!” A star: Mariastern (Mary, the Star)! When he told her that they wished to start a second monastery, she continued: “Now I see Saint Anne with the Child Mary. Mary is blessing you with an anchor – a sign of hope for you!”

Fr. Francis confided to her that he was traveling to Rome but would return and bring her the blessing of the Holy Father. Would she kindly hold him and Mariastern in prayer, because it was not easy to face a hostile world and all the obstacles laid in his way? She replied: “You need not fear, for at today’s Mass the Mother of God offered you a crown, and what a beautiful crown that was! If only you had seen it for yourself!”

The long train ride to the Eternal City gave the Prior plenty of time to ponder what he had heard. He still had his doubts: What if the devil was playing tricks on him? But after turning the matter over many times he drew the following conclusion:

“If these visions are from the devil, he must be a stupid one, because what he has achieved is the opposite of his own natural intention. He has set my heart on fire with a stronger faith, greater hope and more love than I ever felt before. He has also made me pray more fervently. So he has failed miserably at his own game! I should thank him for that! … It is simply not possible to believe that the devil goes around, like a guardian angel or missionary, urging people – many people! to be good! Satan cannot be anything but evil and incite others to evil. Therefore, the visions of Wittelsheim cannot be tricks the devil plays with peoples’ minds.”

But what are the facts about these apparitions particularly Mrs. Schott’s? Fr. Karl Luttenbacher CSSp, himself a native of Alsace and for many years confessor to the Missionary Sisters of the Precious Blood at their motherhouse in The Netherlands, did the necessary research. From Mrs. Schott’s youngest daughter, Mary, he found out that her mother had died in 1897 and that her father had followed her two years later. Her blood sister Eugenia had become a nun at Nancy. She had been cured of a serious illness at Lourdes and lived on for another thirty-eight years. Her brother, Abbe Schott, had been a parish priest in Paris for fortythree years and died at Wittelsheim in 1945, at the age of eighty-two. She also told the Prior that after he had published his brochure about the visions many more people had come from Germany, Austria and Switzerland to personally see the place, but with the outbreak of World War One their number had dwindled and not increased again. Her mother had been taken into custody for six weeks when another woman had slanderously accused her of telling lies about her deceased family members. However, the parish priest, Waltzer, had always defended her mother and especially when the case was taken to the local ordinary. Waltzer had regarded her mother as “the main seer of Wittelsheim”, and had taken care that the relevant documents were eventually archived in Strassburg.

So much for Wittelsheim. At Mariastern, progress was in full swing. Vocations poured in from everywhere. Shortly after the Prior’s return, the diocesan priest, Karl Gabl from the Brixen diocese entered and was given the religious name Dominic. With the number of priests increasing, a new foundation was just a matter of time. On 18 November 1874, Nuncio Ludovico of Vienna sent a five-page dossier to the Cardinal Prefect of Propaganda Fide, explaining Mariastern’s intention to found a second monastery and an orphanage in the interior of Bosnia. What he did not mention was Vuicic’s resistance. That is a subject we must leave for another chapter. First, we will look at one of the Prior’s most unique vocational appeals.

Reflections

By Francis Pfanner

The Good Lord knows that I have never sought office or leadership. When I was appointed to my present role I accepted it in obedience to God and I am also ready to lay it down again when asked to. – A kind word spurns me on to sacrifice; but I do not bow to accusations and threats.

Pettish, thin-skinned people lack flexibility. Touch them and you will find that they are as brittle as glass. They break as soon as anyone tries to change them, if ever so gently.

What exchange! God gives himself to us if we give him the little we have!

Open your eyes: The world is one big wonder! We are surrounded by wonders!

To rejoice with Jesus means to have triumphed with him.

The joyful cry “Christ is risen!” is a pledge that the promises Jesus made in the Eight Beatitudes – to the poor in spirit, the meek and peaceful, the bereaved and those of pure heart, the merciful and persecuted for his sake – will be fulfilled.

VIII.

A Promotional Campaign with a Difference

“Are you a Chimney Sweep?”

The title which the Prior of Mariastern gave to a brochure he wrote in 1874 immediately caught the public eye. A modern journalist could not have done better. Fr. Franz tells us how he chanced upon it. In the Convent Lane in Agram he had been asked by an elderly gentleman “with the collar of his coat upturned and probably a member of the liberal camp”: “Are you a chimney sweep?” – “No, not exactly!” he had replied. “Why ask?” Stuck for an answer, the other had stuttered in broken Croatian: “I not know what think of your black cap!” Amused, Fr. Franz had told him who he was: a Trappist vowed to perpetual silence.

The question the man in the lane had asked followed him. Wouldn’t it make an excellent title for an article on religious vocations particularly the vocation of a Trappist? Spontaneous as he was, he sat down to put his thoughts to paper and published them in a brochure. Timotheus Kempf CMM comments on it: “It is spiced with biting scorn for the liberal spirit of the time”. Perhaps it is. Fact is that its wit and humor – often at the expense of the Trappists themselves – attracted a lot of readers. A Trappist, for example, is described as one “who loves trapping” or, in a slightly more serious vein, “a creature who, though endowed with normal reasoning power and free will, prefers to inhabit woods, gorges and solitudes. He is like the donkey, working hard for a frugal fare and, as Scripture says: thinking a lot but speaking little.”

The author describes St. Bernard as one who entered religious life in order to find God. He founded no less than sixty-nine monasteries in solitary places and filled them with men who wished to live as he himself did. But when discipline among his Cistercians deteriorated, a second Bernard arose in the person of Armand Jean le Bouthillier de Rancé (1626 – 1700), who “two hundred years ago taught his followers to go back to the original lifestyle of the Cistercians by acting foolishly according to the standards of the world, shunning human company and observing perpetual silence. And because this happened in some godforsaken corner in France which was called ‘La Trappe’, all those dumb monks, whom the world considers lunatics, were called Trappists.”

Trappists, the Prior explained, were vowed to asceticism, something people found hard to comprehend. Because they could not grasp the sense of such a life they made fun of it, saying that fasting made dull and silence, grumpy; that drinking little caused lice and saying long prayers was good only for screws. Such objections, however, were not to be taken seriously:

“The Trappist earns his bread by the sweat of his brow as the world expects it of religious. But without asking anyone’s permission a Trappist also takes the liberty to offer his sour sweat to God for his own salvation and that of his friends and benefactors, including those who flagrantly go astray in the world. … Silence serves a material as well as a moral purpose. Or why do factory owners forbid their employees to talk during working hours? To make them work harder, don’t they? It is well known, that one who talks much, works less. Moreover, silence keeps one from committing many sins such as slander, libel, giving false witness, lying, cursing, blaspheming, cracking dirty jokes, speaking ill of religion, etc … – However, to observe silence is not their prime purpose. Their main aim is ratherto attain, even in this life, the bliss which the saints in heaven is enjoy: intimate union with God. Or how does anyone who chatters nonstop hear the voice of God speaking in his heart?”

Who is fit for the Monastery?

Prior Francis believed that, with very few exceptions, everyone qualified to become a monk, if only he was determined to be a good one. Exceptions were men who were very clearly not “cut out for it” and others who did not meet the criteria which, as we shall see, he laid down in inimitable fashion. Such men should rather remain “in the world”.

The Prior’s list of eligible candidates is long and, arranged in alphabetical order as in the German original, quite whimsical.

“Who may apply?

1 Young men, from fourteen years up. Nota Bene: Contrary to Croatian opinion, that Trappists put the cowl only on criminals and convicts, these include innocents.

2 Old greybeards: they make a fine view, especially next to milksop novices. The sight of a silver-haired old man following on the heels of a callow youth with childlike simplicity is truly touching.

3 Artisans: these are most welcome because we make everything ourselves and also share our skills with others.

4 Unskilled workers, including most priests: in the monastery they serve like ordinary domestics on a daily basis and for fixed periods of time.

5 Students and academics: that they may finally put their books aside.

6 Unlearned and ignorant people: that they may be taught never again to dream of studying or appearing learned but stick to their knitting.

7 Unsuccessful students: because in a monastery where no one leads these dissolute fellows astray they may still become disciplined members of the human race.

8 Good students: if their aim is to become Trappists, but not necessarily priests.

9 Poor people: that in the company of equals they may become more content.

10 Rich candidates: we do not disdain these, for they may help us build up our monasteries and support our orphanages, if perchance they do not give away their possessions before they entered.

11 Strong men: that they may give a hand with hard manual labour.

12 Weak men: they are quite useful for sweeping the house and watching the geese.

13 Deformed and handicapped men, including those whom Jesus finds along highways and byways: for they are also invited to the great banquet.

14 One-eyed men: Jesus says that it is better to lose an eye and save one’s life than be lost with both eyes intact.

15 Greyed sinners and young villains. If they honestly wish to do penance, such people look rather nice next to innocent monks. According to the Lord’s command they must take the place of those who were invited first but rather than come to the Banquet, preferred to get themselves a wife, a farm or five yoke of oxen.