Полная версия

The Apostle of South Africa

III.

Pilgrimage to the Holy Land

Sightseeing in Egypt. Farewell Letters to Friends

Fr. Pfanner was still waiting for a reply from Brixen. The bishop was a former seminary professor of his and took his time, since he knew him well.

Meanwhile, the Severin Association of Vienna was looking for a priest to lead a group of pilgrims on a tour of the Holy Land. The advertisement was a heaven-sent for Fr. Pfanner. He immediately applied and being just as promptly accepted, began to make preparations. First he ordered a proper saddle from the workshops of Lepoclava, because Arab saddles, as he was told by travelers to the Near East, were sheer torture for Europeans. To the Sisters, however, he did not breathe a word about his plan to become a Trappist. They thought that he wanted to improve his knowledge of Scripture by going to the land of Scripture. But to his bishop to whom he wrote a second time he did confide that he wished to see the Lord’s homeland before burying himself in a Trappist monastery.

The group he was to guide met at Trieste. There he was given his official appointment and all the faculties he needed as president. Apparently, the organizers had been told that he spoke Italian and a little Arabic. Above all, they seemed to have known that he was not a coward. The group was mixed and manageable. It included three priests. One of them, a teacher of Religion at a gymnasium in Bohemia, he appointed treasurer. Then there was a rural pastor in his seventies, also from Bohemia, and an assistant priest from the Diocese of Regensburg. A young probationary judge from Wuerzburg was made secretary. But a Hungarian pensioner proved such a pain in the neck that “we would have been better off without him”. No one in the group had ever been outside his home or traveled. They boarded a steamer destined for the southeastern ports. As soon as it put to sea president Pfanner, like most other passengers, became seasick. “Only my secretary was spared the scourge!” They traveled via Corfu to Rhodes and Cyprus and from there to Lebanon.

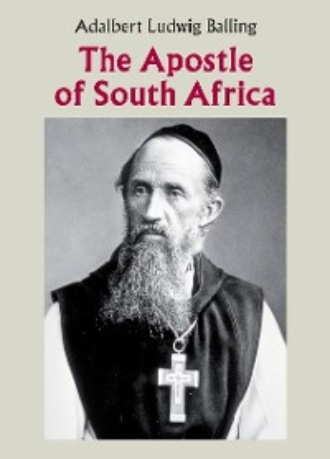

Wendelin Pfanner (Confessor to Sisters at Agram, Croatia) as pilgrim’s guide to the Holy Land

In Beirut, he bought a riding crop to keep away “the crooks and rogues” who lay in wait at every city gate to pillage and plunder unsuspecting pilgrims, not simply demanding but extorting bakshish. He did not hesitate to lash out at them, commenting that “nobody would have suspected this whip swinging commander to be a kid-glove confessor to Sisters.” The group considered itself fortunate to have him.

Haifa was the first port of call in the Holy Land where they were allowed to go ashore. They climbed Mount Carmel and afterwards sailed to Jaffa (Joppa, Tel Aviv-Jafo) and there disembarked for good. It was a one of a kind experience: Arab porters stood ready to carry them like sheaves through the churning sea, after which they set them down on the beach. Once ashore, they were on “holy ground”. They knelt to kiss it.

The seasickness was gone as if it had never existed. So the tour of the Holy Land could begin.

After his return to Agram, Fr. Pfanner described his experiences in a letter to his mother and siblings, dated 4 June 1863:

“As president of the pilgrimage, I wasted precious time on official errands and visits besides acting as interpreter for my group. During Holy Week, I celebrated Mass in the very place where Jesus was nailed to the cross. I was so moved that for a moment I could not continue with the Prayers at the Foot of the Altar. On Holy Thursday, I had the honour of being one of twelve pilgrims who had their feet washed by the Patriarch of Jerusalem. Yes, this prelate of supreme rank washed, dried and kissed my feet! He also gave everyone a small cross, carved from the wood of the olive trees which still grow in the Garden of Gethsemane where Jesus suffered his agony before he died. On Good Friday, we visited the Via Dolorosa in Jerusalem. We kissed each Station but otherwise felt most unworthy to be without a cross in a place where Jesus carried such a heavy cross! The following night, in the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, we listened to the seven sermons traditionally preached there in seven languages: Italian, New Greek, Polish, French, German, Arabic and Spanish. At five o’clock on Easter morning I was allowed to say Mass in another special place: the very tomb in which Jesus was buried … It was a rare opportunity which not even a high ranking Franciscan enjoys who perhaps spends his entire life in Jerusalem, because priority is always given to visiting personalities.”

When the Easter celebrations were over the group rode to Bethany where Lazarus had been buried and raised to life. Then they continued to the place in the desert where Jesus had fasted for forty days. From there they proceeded to Jericho and the Jordan River. They pitched their tent on the bank and went into the water to fill their bottles. Afterwards they followed the Jordan to the Dead Sea and climbed the hill country to see the Church of the Manger and the Shepherds’ fields at Bethlehem. At Hebron, which they visited next, they remembered Abraham, and at St. John-in-the-Mountain, the Holy Baptist.

So far their journey had been without incident, but on this last leg the president’s horse stumbled. But for the fraction of an inch he would have plunged into a ravine. In another instance the horse did throw him in full gallop, but both times he and the horse got away with a bruise and a shock.

After a brief sojourn in Jerusalem, the president led his group to Sichem to see Jacob’s Well, then up Mount Gerizim and on to Nazareth. Later they climbed Mount Tabor from where they descended to the Sea of Galilee, in order to continue along a road leading to the Hill of the Beatitudes and the plain where Jesus multiplied the loaves. Via Cana in Galilee, renowned for the Lord’s first miracle, they returned to the sea. There they made a cash check.

Abbot Francis:

“Before we left Palestine, we distributed the remaining money. Everyone got back 93 guilders. Latest now they realized that their president had managed the tour to their benefit. They had saved money though they saw more than most other pilgrims … Now everyone was free to choose his own way home, make his own plans and manage his own funds.”

Fr. Pfanner decided to return via Egypt. Would anyone like to come along? Most did and promptly re-elected him leader.

In the Land of the Pharaohs

Embarking at Haifa, they were told that the crossing to Alexandria would take twenty-eight hours. They braced themselves. But then the sea changed; it became so rough and the going so slow that it took them more than twice the length of time: sixty-eight hours! A nightmare for the leader!

Abbot Francis:

“Sailing was torture. I was so seasick that I vowed to myself a hundred times over never again to set foot on a boat. I must laugh as I write this. What good are man’s plans if God makes his own? The proverb that man proposes and God disposes couldn’t be more accurate.”

Yes, God has his own plans. As in Pfanner’s case, so he writes straight also with the crooked lines of our own lives. In Alexandria, Fr. Pfanner stood for the first time on African soil. Little did he dream that this was his introduction to a continent where, further in the south, he would labour for twenty-seven years to establish God’s Kingdom!

Cairo was memorable on account of the Pyramids and the Sphinx but also for an unfortunate incident. Shifty porters cut his saddle bag and stole his coat with his journal. Disappointed and angry, he comforted himself with the thought that “as a Trappist I will have no use for either, my coat or my journal”. Leaving the Pyramids, he and his group traveled far “to the place where, according to tradition, Mary and Joseph had stayed in hiding with their beloved Child”. They also visited the “Mary Tree” and “Mary Fountain” which according to legend had offered the Holy Family shelter and water.

Suez on the Red Sea – the canal was just then being built – was their next destination:

“Our short stay at the little town of Suez turned into a distressing experience for me. I caught dysentery, wide spread in those parts, which confined me to my room for several days. Relief finally came in the form of a remedy the hotelkeeper offered: rice cooked in unsalted water. Later, in Bosnia, I prescribed it to great effect for my sick Brothers, and when I was in London I was able to cure a whole family with it.”

The group disbanded at Suez and everyone went home by his own way. Fr. Pfanner chose to travel via Constantinople “on the same ticket and for the same fare”. He was much impressed with the Golden Horn and a cruise on the Black Sea. From Kuscendje he journeyed by train to the Danube and by a Hungarian steamer up that great water way to Belgrade and Semlin. There he transferred to a Sava-boat and later once more to a train which eventually took him to Agram.

“When my coach drove through the convent gate and I got off, no one welcomed me. Sister Portress did not recognize me on account of my pilgrim’s beard which, as a matter of fact, had not felt a razor for fully three months! I wore it for three more days and during that time paid my respects to the cardinal archbishop.

The glory of the world and its pomp held no more attraction for me. I was only waiting for the letter that would allow me to leave the world. There were all kinds of letters waiting for me on my return but none from my bishop. So I wrote again. This time I mentioned my visit to the Orient and the Holy Land and that everything was but vanity. The only wisdom, I concluded, was to serve God in order to see him when life was over.”

This time the bishop answered by return post. He wrote that he envied Pfanner his “holy solitude” and would love to hide himself away as well, if only he were free.

Goodbye to the World

Before leaving the world for good, Fr. Pfanner took leave of close relatives and friends. In a letter to his classmate Berchtold, pastor of Hittisau in Vorarlberg, he recalled their ordination thirteen years earlier and touched on his recent experiences. Returned from a great journey that took him: “from the cedars of Lebanon to the Red Sea with its pearl oysters”, he had no words to describe what he had seen and felt. He could only hint, for “at such times the heart is drowned in the joys of a world it has never known”!

The Feast of the Nativity of Mary (8 September) was reception and profession day for many of the Sisters in Agram. Fr. Pfanner preached the sermon and afterwards joined them for supper and Evening Prayer. Then he retired to his apartment. He wrote a few more letters to his loved ones and later that evening asked the mother superior for additional traveling cases. She looked at him, apprehensively: “Where are you going, Father?” He: “I leave tomorrow morning early to become a Trappist.” Thunderstruck, she cried: “Oh no! I cannot agree! Before you came, over thirty sisters suffered from scrupulosity. You helped them overcome it. But now I have to carry this heavy cross again by myself.” The good woman broke down, but he did not allow himself to be moved. Only to a friend he confided in a letter: “It is not easy to pull myself away, but I must follow my inner call. I want to live out my days in seclusion and solitude … I desire nothing more fervently than that God would accept my resolution. Please, remember me to your loved ones and pray for me that I do not waver in my resolution.”

His mother and siblings were still in the dark about his decision. His farewell letter to them is dated 8 September, 1863, like the others:

“I am leaving Agram for good. Tomorrow I travel to a Trappist Monastery in the Rhine Province in Germany. I recognize that this is God’s will for me, just as I recognized thirteen years ago that I should become a priest. My bishop in Brixen has approved of it … I have no desire for wealth, prestige or honour in this world. My only wish is to live poor and unknown for the rest of my life, if at all they can use me in the monastery. I beg you to pray for me that I may have the strength to do all that is asked of me … Farewell. Live in such a way that one day we will meet again in heaven! My brothers and sisters, support our old mother. Ease the burden of her responsibility for the family by rendering her obedience.”

Serious and Humorous Thoughts

By Francis Wendelin Pfanner

The principle I followed when I was in school was to do all my assignments, but not a thing more than was required!

Pride and foolishness belong together and are hatched by the same hen. As long as the world lasts there will be foolish and ignorant people.

The sinister fellow is not the one who looks for light and enlightenment in the dark, but the stay-at-home who, too lazy to think, does nothing but roar from the dark.

If the heart is at peace it is easy to pray. Look at the water. When its surface is calm, you can look through it and count every pebble on the floor.

It is an art to live in a religious community and rub off your shortcomings and rough edges on the shortcomings and rough edges of others.

IV.

Mariawald Monastery

Praying and Working with Silent Monks

Fr. Pfanner traveled to Cologne via Vienna. At Wuerzburg he looked up his “secretary of pilgrim days”, while in Cologne he waited impatiently for his connection to Heimbach, the station closest to Mariawald:

“For three long hours I sat in the cathedral, but this time I had no eyes at all for the gorgeous stain glass windows or the gothic architecture, which fourteen years earlier had cast such a spell over me. ‘Why should I?’ I told myself; ‘it’s pure vanity! Once in the monastery, I cannot share what I have seen with anyone’.”

Climbing for an hour through a gorgeous beech wood he arrived at Mariawald. The monastery had been secularized in 1802 and the monks expelled. Two years before he knocked on its door Trappists from Oelenberg in the Alsace had resettled it (1861), but the actual work of reconstruction had only just then begun.

Abbot Francis:

“The beautiful Gothic church had no roof, windows or doors; even the iron bars had been broken out of the ashlars and carried off. The miraculous picture of Our Lady had been transferred to the parish church of Heimbach, where it was preserved in a separate chapel. The beautiful Gothic windows ended up in a museum in England and the monastery buildings had served as a quarry for anyone who needed stones. – The farmland was extremely poor and rocky and there was hardly enough level ground to build on.”

When Fr. Pfanner arrived on 10 September, 1863, Mariawald numbered not quite twenty monks. At thirty-three years of age the Prior was five years his junior. He was away in France attending the annual Trappist general chapter. Until his return the candidate was put up in the guest quarters. Six weeks later, on 9 October, the feast of St. Abraham, he was given the habit of the Reformed Cistercians and a new name. As Fr. Franciscus (after the Poverello of Assisi) he became a member of the Trappist Congregation of de Rancé.

His life was now ordered by the rule with its daily schedule of ora et labora.

Abbot Francis:

“My first assignment was to weed the garden. So I had to bend a lot. It was something my back did not like, but since no one asked me how I felt, I carried on, telling myself that in due time I would be given another occupation. I was mistaken. Instead, I realized that all that was expected of me was to help rebuild Mariawald … Time passed quickly. As I became better acquainted with the life of a novice and entered more deeply into the meaning of the Trappist vocation, things became easier. I even started to doubt if after all this was the life of penance I was looking for.”

To an extent, it was. In mid-18th century Mariawald was certainly not a place of bliss. What annoyed the beginner (novice) was that the study of the Psalms (by Bellarmin) was constantly interrupted by a rigid schedule of prayer and work. He got on well in community but not with everybody:

“One of the older monks who wanted to try me out was known to be difficult. He did not want to see me going flat out, because for him, who used his many private prayers as an excuse for not doing his chores, manual labour was an evil he shunned any time. It did not take me long to figure him out. He was not really a Trappist but what you would call a holy Joe. Himself neglecting his share of the work, he made sure others got more than they could cope with. For example, when we were repairing the roof he put so many slabs in my basket that not even two men could lift it. I carried it up a few times and would have continued doing so if my superior had ordered me to, but I also knew that it was against our rule to carry or assign too heavy burdens.”

Fr. Francis worked with a will. Work was a pleasure for him. Before he knew it he had regained his former strength and felt better than ever before. The ascetic lifestyle – frugal diet and hard labour in the fresh air – had an invigorating effect. He did not wish for a change. To his family he wrote that though he had no mirror to look at himself he could feel his cheeks bulging out. He was busy the whole day, either chopping wood for torches or cutting and uprooting thorns: in short, cultivating barren ground. It was the kind of work that agreed with him, and it did not matter that his hands “like the hands of a farmer” were full of calluses and cracks. Rather, he must thank his father for teaching him early in life how to work with wood and soil.

His former parishioners insisted on his return to Haselstauden. He did not think of it. Instead, he wrote to his bishop that he would renounce his benefice immediately after profession.8 So fully was he committed to the monastic life that once he had pronounced his simple vows, on 21 November 1864, he was appointed Sub-Prior.9

Daily Striving for Perfection

The monastic regimen is not soft on a man. The Mariawald community rose at a time when most other people are still asleep: at 2 a. m. on weekdays and 1 a. m. on Sundays and Holy Days. The Trappists kept perpetual silence: they did not speak without permission and then only what was absolutely necessary. Communication was by signs or the sign language. Their diet was frugal.

Abbot Francis:

“We eat everything except meat, butter or lard, eggs, fish, sweets or delicacies and use no spices. Oil is used only for salads. Instead of (Arabic) coffee we drink a brew made from barley and an additional mug of wine or a pint of beer … The Brothers take three meals a day. A hot meal is served at noon. Mornings and evenings we eat bread.”

Like everything else, the liturgy at Mariawald was sombre, devoid of all decorative detail. On special feasts such as Corpus Christi, Sacred Heart, Peter and Paul and the Visitation, the Prior preached a sermon. For Fr. Francis, who was used to preach every Sunday, this was something to get used to. He did not always manage. Once, when the Prior was again in France and he substituted for him, he preached to his heart’s content. The Brothers were delighted but some of the older monks were not. They complained and also criticised him for hearing Confession in Heimbach, where, as they had heard, people were flocking to his confessional. They warned the Prior that if Fr. Francis was not stopped, his popularity would destroy him. The result was a heated altercation between the Prior and his Sub-Prior – the one a Prussian and the other, a Vorarlberger. Fr. Francis, who seems to have taken it lightly, later referred to it as a lesson he needed to learn:

Mariawald Monastery in the Eifel, Germany, where Wendelin Pfanner entered to become a Trappist

“I have never regretted coming to the monastery. The Prior is not the monastery. Nowhere except in the monastery would I have known how deeply the tapeworm of my own ego was still lodged in my heart. Neither would anyone have pulled it out for me, for that favour they will do you only in the monastery.”

Soon afterwards Abbot Ephrem van der Meulen – Abbot of Oelenberg and Founder and Pater immediatus10 of Mariawald – recalled the Prior and appointed Fr. Eduard Scheby his successor. Scheby, Danish by birth and originally a member of the Lutheran Church, had converted to Catholicism in Vienna. First he had joined the Redemptorists in The Netherlands where he was ordained, but later he had become a Trappst at Mariawald.

Abbot Francis:

“Scheby was one of those people who dream a lot and allegedly hear God speak to them in visions. Such men may be capable after a fashion but they definitely do not make good heads of monasteries because they only confuse and mislead their unsuspecting subjects.”

Wendelin Pfanner, now Fr. Francis, could distinguish between an authentic monk and a fake one or “holy Joe”. Scheby had hardly assumed office when he made the former Sub-Prior his private secretary and Master of Brothers. Fr. Francis filled these positions to the best of his ability. But before long, he found himself at odds also with the new Prior. Scheby accused him of using the confessional to instigate the Brothers against him. The fact was, however, that Scheby himself had forfeited the Brothers’ trust and respect on account of his gross mismanagement. He also upbraided his Sub-Prior and secretary for lack of monastic piety and discipline. Was he not actually breaking holy silence quite frequently and without reason? In short, Scheby did not think too highly of Francis. And the other monks, how did they see him? Br. Zacharias spoke for several others when he suggested that Fr. Francis lead them in establishing another monastery where they could follow the strict observance of the rule without any hindrance. Would he consider such an undertaking? Fr. Francis was not disinclined but needed time to discern. Time was not granted him, however, because when the proposal was put to Abbot Ephrem he took matters into his own hands. He ordered Scheby to send Fr. Francis and Br. Zacharias to find a suitable place for a new monastery somewhere in the Danube Monarchy (Austria-Hungary). They were to be the vanguard; later he would send more monks.

Off to an Unknown Future

When the day of departure came, Fr. Francis had only one wish: to be given permission to say a word of farewell to his fellow monks. But no permission was given him. All he and Br. Zacharias were allowed to do was to exchange the customary kiss of peace – in silence! Their letters of reference, issued by the Prior, stated that they were seasoned monks and in every respect capable and worthy to prepare the ground for a new foundation. They were provided with “an old Missal, a second habit and travel fare to last us for a few days”. It took them as far as Mannheim where they would have been stranded had not a kindly man taken pity on them.

Abbot Francis:

“A cleaner of street lamps in the service of the Grand Duke took us to his house and gave us enough to continue on our journey. We were like the girl in the fairy tale ‘A Girl with Empty Pockets’.”

From their letters (decrees) of obedience the two pioneers learned what plans their superiors had and how they were expected to carry them out. The letter issued to Fr. Francis read:

“We, Father Eduard, Prior of the Monastery of Mariawald in the Order of Citeaux or La Trappe, extend to the priest Francis, professed member of this monastery our best wishes for his journey.

It has long been our desire to see our Order – the Reformed Order of Citeaux originating in France – spread also to countries in the south eastern parts of Europe. But until now we have not been able to carry it out because of the few admissions we have had to our relatively new monastery in Germany. However, with God’s help membership has increased. Therefore we have decided to open another monastery in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. We send you, Fr. Francis, to find a place for it in Hungary, Croatia, Slovenia or one of the neighbouring countries. We grant you a three-months leave-of-absence to carry out this mandate and we ask all rectors of churches to grant you, a genuine monk, admission to the Sacraments and other spiritual assistance … We affix our signature and the Seven Seals of Mary of Citeaux to this letter as proof of its authenticity. – Given at the Priory of Mariawald, on the 23rd day of July, 1867. Fr. Eduard, Prior.”