Полная версия

The Great Hollenberg Saga

However, the Imperial Court or his herolds had to intervene rather regularly in those many disputes and struggles for power between the clerical (bishops) and secular (dukes, counts) authorities. Thus, within this kind of medley, the initially granted privileges became over the following centuries hereditary.

Although Charlemagne had according to the Franconian Statutes not formerly renounced private property per se, the handwriting of history had taken a somewhat other turn:

Another pillar of Feudalism had established itself,

Resulting in a two class-society that lasted nearly 1000 years and put its face onto the history of Europe:

A society of those with power and the might of control – and the remaining others,

who had to live their every-day-life or just endure it.

These were the centuries where the structures of the secular power concoction and the clerical interests found opportunities and time to solidify themselves to last way into the Renaissance with different results to be classified as good and bad:

The “good” – part, beginning with the 15th century, was especially the rapid development of civilization, the discovery of the world-wide globe, the letter-printing, and above all the new dimensions in art and philosophy.

The “bad”- part were the many skirmishes of those many small potentates, the rule of the mercenaries, and those many courtiers serving the sovereigns to show their glitter and pomp to the world.

And yet, despite those contradicting conditions, this period was nevertheless a deeply religious epoch which included both, Martin Luther with the Bible as well as Savonarola burning pictures on Italian market places.

What then followed, after 1500 A.D., can be confidently called the “bloody Renaissance”. It was not the idealistic humanity anymore that dominated, but rather the fanned fear of Hell and Devil, growing into a militant intolerance against any deflection in religion and believe and ending in multiple religious conflicts throughout Europe. And as if this wasn’t already enough, there were epidemic events like the “Black Plague”, also called the “Black Death”, which swept the world in the 14th century, reaching Europe at its peak around 1350 A.D. and reducing the population there by one third. Two other events, even more profound, caused thereafter dramatic spititual, economic and social changes:

These two carnages, the “Thirty-Year-War” (1618 -1648 A.D.) and the “Witch-Hunt” or “Witch-Cremation” period of the 16th and 17th centuries, were undoubtedly the ultimate peak where mercenaries and soldiers massacred the population as never before – under the jubilations of theologians on both sides. Both events perpetuated the egoistic politics of the Central European powers and firmly established the split between Catholoc and Protestant Europe. At the end, Spain lost its military supremacy it had enjoyed before.

Humanity suffered through-out and was in certain areas not even existing anymore. Central Europe experienced an awesome long period of two belligerent parties – the Clericals (Pope, bishops, etc.) on one hand and the Seculars (Emperor, nobility, etc.) on the other – fighting stubbornly and mercilessly, without pitty, about their predominance in power and faith. All this happened on the back of mostly uneducated people.

Thus, and with hinsight, several hundred years later, it’s more easily to clarify many particulars and courses of the time: Was the “Reformation” just a lucky btreak or a misadventure of history?

It depends on one’s particular point of view. Within this framework, Luther and the Reformation were at the time only a part of this development. Others were climate change (“Little ice-age”), resulting in crop failure, inflation, hunger, general poverty and a high mortality as additional contributing elements.

At the same time, however, while Richelieu modernized France and England lived through a golden age under Queen Elisabeth, the bulk of the people – mostly uneducated – suffered in an unknown monstrosity under the century old quarrels between the Clerical and Secular powers. The Church used this framework to denounce and eradicate the so called “leftovers of the old paganism”: Many thousands of people lost their lives in the subsequent purgatory of witch-hunt. It was the wilful intention to subjugate the people to the “Only blessed Creed” – or turn them fugitive. Church and history called it Inquisition.

This, by all means, is a situation comparable to the dictatorships of the

20th century as well as those most recent events in the Middle East.

The property and other assets of the ”cleaned” or just burned in the inferno of the purgatory turned up as an additional fortune at the cash-register of the Church.

When tourists from around the world visit today those wonderful monasteries, churches and other buildings of the baroque period, it should not be forgotten that this splendour is owned in part to the extortions of the witch-hunt during the 16th and 17th centuries. Thus, the many sorrows of the persecutors did help the “Only blessed Church” to shine again with new saints and lots of gold and glitter.

All this was generally speaking, an ideal presupposition for the exodus of millions of people, leaving their home base in Europe to venture for the newly discovered “New-World”.

Following the timetable over centuries, the “Tithe” was initially only a tax or an assessment and later turned into different forms of bondage, lasting well into the 19th century, including a variety of services as well as military duties. People were fighting or just leaving for better horizons, aiming early-on for Eastern-Europe and even along the route of the crusaders and later-on, when mobility made it possible, for America.

While on the move, many stayed, and depending on circumstances, did accept new customs and beliefs.

Exemplary, for a number of events between 1175 A.D. and 1190 A.D. give support to the above assumption: Friedrich I, called Barbarossa (“red-beard”), since 1155 A.D. Emperor of the “Holy Roman Empire of German Nation”, was struggling with his cousin Henry the Lion (Heinrich der Löwe, at the time Duke of Saxony) for power. Henry was a son-in-law of Henry III, King of England of the house of Anjou or Plantagenet. Each side had found help among secular rulers (e.g., Albrecht of Brandenburg, Ludwig of Thüringen, etc.) as well as highest representatives of the Church (e.g., Archbishop Philip of Colon, Archbishop Wichmann of Magdeburg etc.). Among the warriors on the side of Barbarossa and Philip was also Count Simon of Tecklenburg, secular ruler of our area, with his knights.

In 1179 AD, troops of Henry the Lion rampaged through Westphalia and defeated the supporters of Barbarossa in a battle near Osnabrück. They captured and imprisoned Count Simon and his knights. Most of the followers were slain, only a few were able to make it back to the fortified base at Tecklenburg to report the desaster.

A year later, the combined forces of Barbarossa subdued Henry. The dukedom of Saxon was then broken up. The western part became the dukedom of Westphalia and was given to Archbishop Philip of Colon for his support of Barbarossa. Thereafter, Henry submitted and was pardoned. He moved to England to his father-in-law, Henry III.

Years later, Barbarossa is leading the 3rd crusade, drowns and dies. His son is chosen Emperor as Henry VI (1165 – 1197).

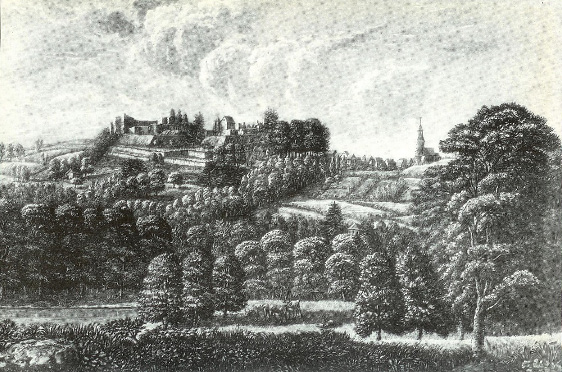

As far as the count-ship of the counts of Tecklenburg is concerned, over twenty generations of Counts (Earls?) were ruling their territory from around 900 AD till 1707 AD when Count Wilhelm Moritz von

Solms-Braunfels finally sold whatever was still under his control to the King of Prussia for a total of 425.000 Taler (= 637.500 Gulden). The county cash-box had been empty, the castle run-down and an over hundred-year-old legal struggle with family members of Tecklenburg-Bentheim had tired him. He died three years later. (Below, picture shows the castle of Tecklenburg.)

These ruins give an indication of the former largeness of the castle.

Thus, bringing to an end eight centuries of eventful ups and downs during which the Counts of Tecklenburg had for some period noticeable influence within the Imperial Court, however limited to the early part of the Middle-Ages.

The largeness of the area controlled by the “House of Teclenborg” around 1600 AD

is illustrated best by the cartographer Johann Gigas, as shown below:

The area encompassed noticeable more than todays ‘County of Tecklenburg’ and included regions around Osnabrück and Münster as well as Bentheim in the West.

Johann Gigas (“Johannes Gigante”, Medicus and Mathematicus, Professor zu Münster und Steinfurt) was born ca. 1582 in Lüdge/Westfalen and died ca. 1737 in Münster/Westfalen.

After studying in Wittenberg, Basel and Padua, he promoted to a Doctor of Medicine and became a wellknown personal physician. Münster/Steinfurt were now the center of his life. He married 1603 Maria von Dorsten and had had 8 children.

Besides his medical services, he also acted as a cartographer and painted the map shown above.

(The picture is property of the author)

The initial foundations of the fortified stronghold, located strategically on the mountain-ridge with open plains to the North and South, were started around 900 A.D. by Count Wilhelm of Tecklenburg. The early members of this nobility string seem to have developed a rather reliable relationship to King Henry I, who became Duke of Saxony in 912 A.D. and was elected King by the Saxons and Franks in 919 A.D. Five years later, the “Magyars” were threatening the territory and the King ordered every ninth “male” to the defence. Some time later, the King decided to press northward to put the Danes under his vassalage (934 A.D.), and in 935 A.D. Count Wilhelm was a“praised participant” in a tournament in Magdeburg. Both, Count Wilhelm and his successor Herman were obviously involved in the rise of King Otto I who succeeded his father Henry in 936 A.D. and who became later German Emperor initiating the “Holy Roman Empire of German Nations”.

King Otto gave many dukedoms and bishoprics to his friends and relatives. He extended his influence, not only just safeguarding the North and East, but pushed into Bohemia, Danemark and Poland to enforce his vassalage upon them.

It’s more than reasonable to assume that vassals of the Count of Tecklenburg were among those supporting the King, and the vassals sons came from the farms of our territory.

Was it adventurism or a left-over migratory instinct? We don’t know.

Both, the reigning nobility and his subjects were after the fortune of their life: The Count or Duke by the power of his sword and the poor vassal by the tempting idea of freedom.

Religious allegiances were forced upon, only few freely chosen.

While Charlemagne initially decreed Christianity in his territory in Central Europe, later on, religious matters throughout Central Europe were top-down decisions, either by religious or secular rulers. The rule always was: “The folk goes, as the ruler goes”.

Quarrels within the Catholic Church during the Middle Ages, leading up to the Reformation with all its consequences, had two noticeable effects in reference to the topic of this book:

At the home base, the Reformation caused changes as well. Shortly after Luther’s Proclamation in Wittenberg, the Count of Tecklenburg, the secular ruler in our area at that time, turned very soon “Lutheran Reformist”, and this is still today very much reflecting statistical religious affiliation there. While the territories surrounding the old County of Tecklenburg (“Grafschaft Tecklenburg”), the bishoprics of Osnabrück, Münster and Bentheim remained Catholic, the present day County of Tecklenburg is still mostly a Lutheran-Reformist island.

Those, who emigrated took usually their belief with them and started, particularly in America, a “bottom-up” Christian Community”. This is still very evident in the active church life in their specific communities today, as well as the many signs of the past, such as the grave-yards of prior generations.

[no image in epub file]

If we compare changes in the Church-Life in general in America and in Europe, it becomes obvious that the voluntary approach, the “bottom-up version”, is by far the better path for a viable religion when compared to the historical “bottom down version” in Central Europe.

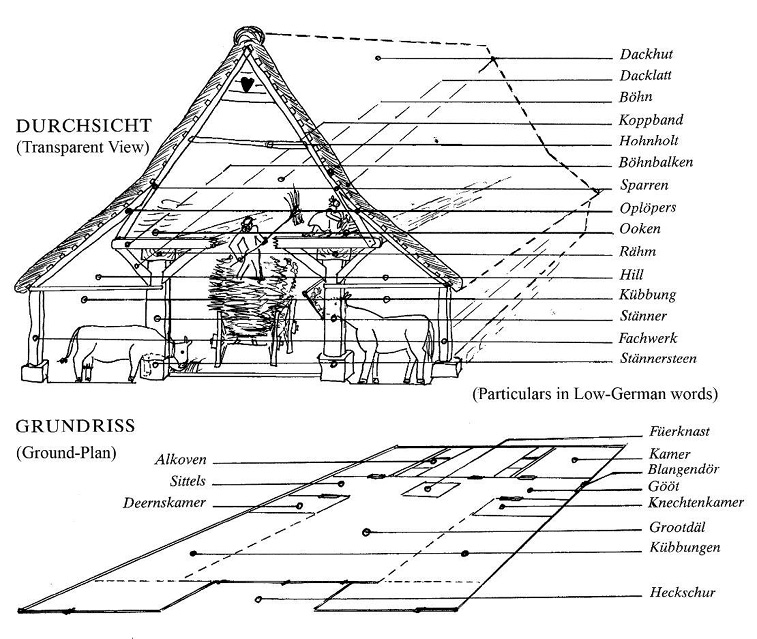

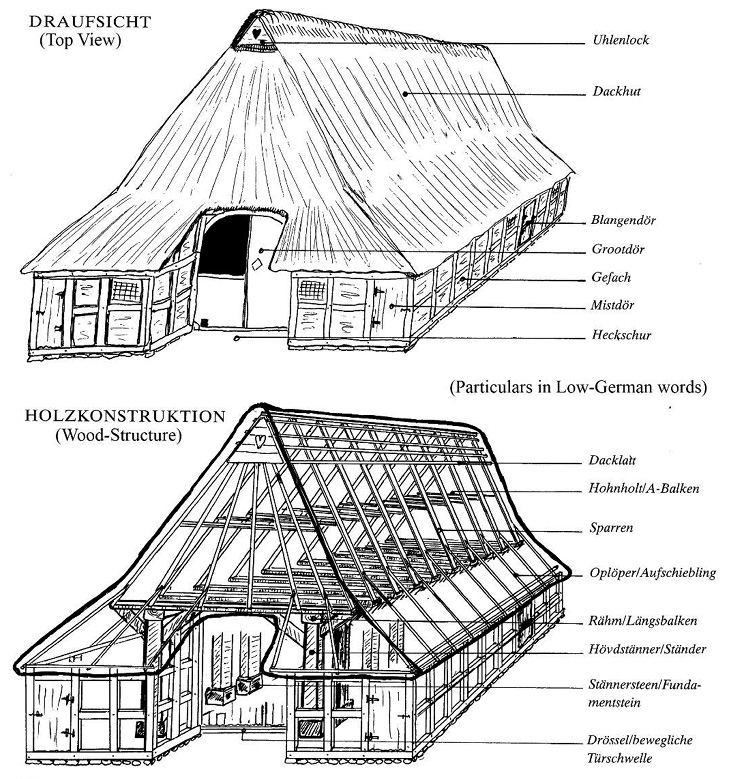

Early Middle-Age Housing Details in the Area

In the mean time, many things around the house and home had changed: (fig.:#14/15)

The older types as shown had developed into various designs of half-timbering structure, characteristically representing even today forms of checker-works of the “Lower-Saxony-Farm-House”.

The simplified version shows how the principle of men and live-stock under one roof was kept.

(fig.:#14)

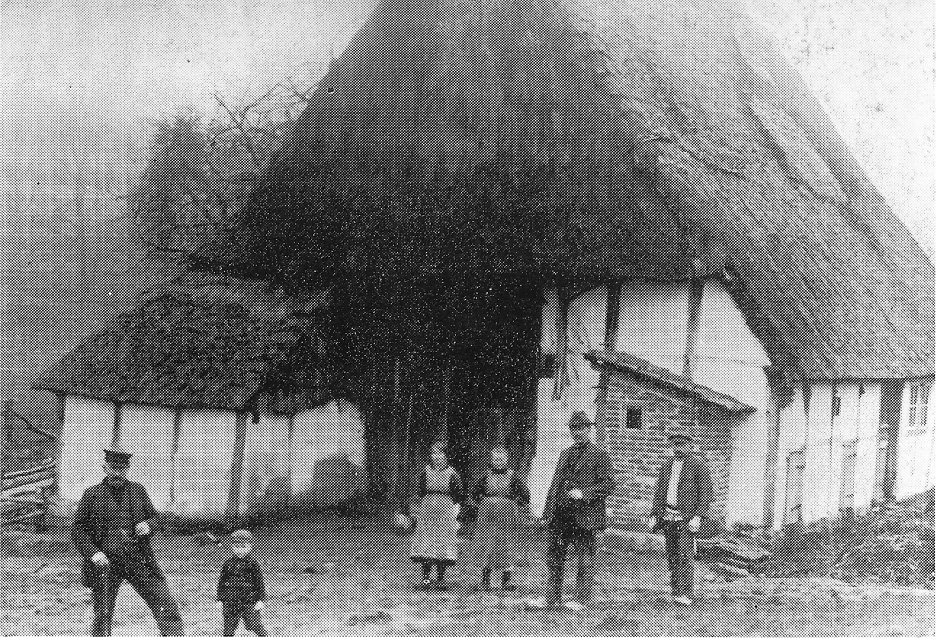

The following picture (fig.:#15) gives an indication of gradual changes till the 18th and early 19th century.

Development of the characteristic checker-works farmhouse in Lower-Saxony.

These typical farm buildings (fig.:#16) were rugged and simple in construction with some comfort for the inhabitants, but basically covering the needs of day by day living. Throughout that period and way into the 19th century, 4/5 of the population was living on farms or making a living of farm related activities.

(fig.:#16)

The “Befiefing” of Old Farms in the Parish of Cappeln

As mentioned before, the Hollenberg property was befiefed on April 14th of the year 1146 A.D. by the Bishop of Osnabrück and the Assembly of the Ecclesiastical Council.

This type of “Befiefing” did change in many ways over the centuries, for example: on September 27th, 1350, the place of “Bernhard to Veldeste” (presumably = Feldmann) in the “Parochia Cappeln” is named, where the Bishop of Osnabrück gives the rights of the tithe from B. to Veldeste to an “Arnoldus de Scarghe”: Thus meaning, that the bishop passed-on his rights of the tithe from one party to another third party.

Exemplary, at the same year, a certain “Johann Wesselmann” paid 12 Denare to the bishop.

During that period, the parish of Cappeln was the only community in the area which produced more grain than needed. This rural prosperity is well documented in the oldest available taxation register of the Count of Tecklenburg from 1494 A.D. The community of Cappeln shows 42 farm places required to deliver 58 pigs. In contrast, the larger parish of Ibbenbüren with 45 farms owed 39 pigs.

The contribution varied over the centuries in details and content as well as the corresponding addressees. The “Befiefing” was the imposition of contributions initially organized by the Church with the backing by the “Franconian Law” established by Charlemagne, and lasted throughout the Middle-Ages till modern times; e.g. in parts of Prussia, including the territory of the province of Westphalia.

During that period, the tithe holder could change and in fact did change many times, e.g., from ecclesiastical persons or entities to secular parties, or to a combination of both.

One example as reported in 1836 for the Niederste-Hollenberg place goes as follows:

1.) Contribution to the King of Prussia in form of taxation:

a.) On the basis of a 10 year average

b.) Tax on cultivated acreage

2.) Contribution to local clergy:

a.) To the First Pastor:

i. A sheaf of grain (1 bushel)

ii. Sausages and bread

iii. One carriage with horses and helper for ½ a day per year

b.) To the Young Preacher:

i. ½ bushel of grain – rye

c.) To the Sexton:

i. A sheaf of grain (1 bushel)

ii. A truss of rye

Some of the above lasted all the way into the 20th century.

In addition to the above, it’s worth noting that the local pastor was doing some farming himself. As described earlier, “Charlemagne established the tithe in the area”: Based on that ruling, the tax register from 1577 A.D. showed the pastor in Cappeln had: 3 horses, 6 cows, 6 young cattle, 5 pigs and he paid per year a onetime tax of 4 Taler, 18 Schilling.

Outside common property, all real-estate was owned by either, the sovereign, the Church and monasteries or the nobility. Thus, all tithe-debtors were with their total property subject to a harsh bondage system.

The un-free farmers were called “Colonus” and those in the County of Tecklenburg were vassals to the Count there till 1707 A.D. and thereafter to the King of Prussia.

However, over time, parties on the receiving end found ways and means to extent and increase the already heavy burden on top of the original “tithe” ruling = 10% on all income. Those extra obligations are described in a reference case of a vassal-farmer in the parish of Lienen as follows:

(ref.: Archive-Urbarium-Hartkotten from 1788 A.D. – between landlord von Korff and a number of farms who were his debtors ).

It says that, outside the annual rent, normal deliveries of livestock and already defined assets of materiality, other additional contributions would be due:

Extra payments and/or other obligations against the tithe-holder:

--- On death of colonus.

--- On taking possession of the farm by an heir.

--- On marriage.

--- On charter for departing children.

--- On take-over by a third party, conditions have to be renegotiated with landlord.

--- All children are subject to hard labor at will of landlord.

--- The vassal is responsible for maintenance of buildings and inventory.

--- Sales and trades need to be reported.

Those “Extras” did not include the average annual contributions for one farm, which amounted for a given example to:

--- 1 Malter Roggen = 165 gallons of rye

--- 1 Malter Gerste = 165 gallons of barley

--- 1 Malter Hafer = 165 gallons of oat

--- 1 pig of 100 pounds

--- 1 Taler, 7 Schilling, service money

--- 2 Taler, 4 Schilling, “May”-money

Plus other additional services as follows:

--- mowing service from 6 AM till 6 PM at the place of the landlord.

--- 4 days with horses and plow, two days in fall, two days in spring.

--- 1 cart-load of wood and 2 chicken.

No food or drinks were provided to laborors.

Changes to the Hollenberg Name

The period between 1200 A.D. and 1400 A.D. was very sparsely recorded, and even then, most trports are based upon ecclesiastical documents written in Latin.

This, however, was a period of noticeable growth in the general population, causing changes of names, double names or combinations. Particularly, rural areas increased the cultivated acreage by turning the forest and wasteland into arable lands. This led in a number of cases to split-up family farms among family members.

Historians, like F.E. Hunsche, are of the opinion that this name-splitting for the initial “Holenberg” or “Hollenberg” place began to develop during the 13th – 14th century, when the family clan decided to break up the estate between father and son.

Initialyy and for an interim period, simple name distinctions were accepted, like:

---- Johan tom Hollenberch de Olde

---- Johan tom Hollenberg de Junge

Throughout times, some other name variations were used – mostly by misspellings or rewriting from one document to another: like, e.g. “Holanberg” or “Halenberg”.

The new units were of about the same size, totally separate and independent. The only visible signs from those former days, when one place was broken up in two, are two old garden gates and a hardened stone passage between the two main buildings of the farm houses, as could still be seen after WWII in the Hollenberg case.

Although there is no actual date for establishing the final name of the two family farms, a tax register in 1494 A.D. mentioned 42 farm places in the parish of Cappeln. Those names are:

de Provest (Probst), Hermann to Segeste (Seeste), Determann, Boye to Segeste, Plaggevoet, de Konynk (König), de Bunemeyger, de Lange ton Osterbecke, Puls, de Sentmeyger, Twyghus (Twiehaus), Dickmann, Sabbensel, Konradinckman (Konermann), Eysmann, de Burrichter, Johan tom Hollenberch de Olde, Johan tom Hollenberg de Junge, Tenge to Gelentorpe, Berchman, Harte to Hambüren, Symon to Leda (Lada), Bernt Wilsinck, de Meyger to Leda, Sprede, Knüppe, de Meyger van Düte, Hynna (a), Hynna (b), Yborg, Rotman, Sparenberg, de Vos to Handarpe, Johan Wesselinck (Wesselmann), de Wylde, de Buddemeyger, Schürmann, Wortmann, Lynneman, Ludeke to Handarpe, Vortman (Fartmann), de Bremer.

From here on, the historical pattern of those farm places had been established and recorded fairly well: Proof can be found in the “Registers”of the compulsory tax for the year 1543 A.D. with details about the tax contributions of the two Hollenberg families as shown below:

Contribution to Church and Crown

During the year 1543 A.D. the two Hollenberg estates had to make the following obligatory payments based upon existing records:

Hermann ton HollenbergJoan ton HollenbergGeldpacht (lease-pay)2 Gulden2 GuldenHerbstschatzung (taxassessment on fall-harvest )9 Schillinge9 SchillingeMarkengeld (tax on acreage)1 Ort=1/4 Gulden1/2 GuldenA little later, in the year of 1603, the payment of “Markenrente” (= annuity for acreage) is, documented for both: -- Erich Hollenberg and Luike Hollenberg --.

Again, 20 years later – 1623/24 –, the “Inventarium” of the archives of the Prince of Solms list the place of “Johan to Hollenberge” and “Lueke tom Hollenbergh” (=Niederste Hollenberg).

At that time, both were subject to tithe payments to the Count of Tecklenburg.

In 1707 A.D., the Kingdom of Prussia acquired the County of Tecklenburg, and that included the Parish of Cappeln. Consequently, that whole district became subject to tithe to the King of Prussia.

Another listing from the year 1770 A.D. shows the parish of Westerkappeln with 106 farms (of a given size) all subject to the tithe to the King of Prussia.

As a consequence of the “tithe” obligations which the operating family farm had to fulfil against the authorities (Church and Crown) and the change of the general economic climate due to the upcoming industrialization, the tenant farmer (“Heuerling”) were caught in between – without their fault.

This forced them virtually to look for additional income on the side in order to make a living: For some time, the handcrafted linen production in the area served this purpose, whereby special “linenkeepers” kept the trading routes on foot open into nearby Holland and the coast-line.

The invention of the spinning and weaving machinery brought this activity to a near halt and intensified the emigration across the Atlantic for this kind of workers and their families.

Another side effect of the “obligation to the landlord” was that practically all farms had to deliver local services to the community within their parish. It meant e.g. providing horse-drawn vehicles when needed to build roads or transport material and equipment. Each parish had to bear the cost for his roads. (incl.: stone-breaking, excavation, side-ditches etc.). The cost of those projects was distributed and billed against the farmers.