Полная версия

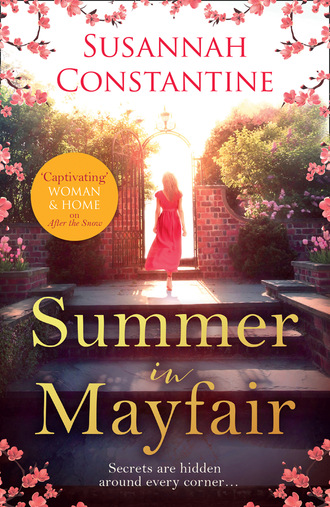

Summer in Mayfair

After giving her a one-second tour of the amenities, Suki left Esme to unpack. A Louis Vuitton trunk that had seen better days doubled up as a bedside table. She would put her clothes in it. Added to that she had a total of two plug sockets, a rickety bed and a hook on the back of the door with three coat hangers. At least she had a bathroom to herself. It was bigger than the bedroom with a panelled tub and skylight. Ancient bottles of Floris bath oils lined the edge of the bath. She picked one up. It was sticky with age and smelt more of cooking oil than the Rose Geranium printed on its label. But since there was no room for the painting in her bedroom, she set it down next to the loo. Appropriate place for the wretched thing, since it was now likely to be worth nothing more than the loo paper next to it.

She opened the window. There was no view, just a redbrick wall that looked like it needed repointing. Pockets of moss grew from cracks in the brickwork. Subsidence maybe, given Jermyn Street was built on an incline. The curtains were dated but she recognized them as classic David Hicks, a geometric design in varying shades of brown and orange. Not what Esme would have chosen but they were lined and thick enough for total blackout.

The bedcover was in the same fabric and reminded her of a ploughed field. Lying down, the mattress felt like it looked; a lumpy, unyielding pad of knotted horsehair that was more like sleeping in a ditch than on a divan. The springs no longer sprung but screeched like a crying baby. Oh well, she wouldn’t be in it much.

‘All settled?’ Suki came back in carrying a desk lamp. ‘Thought you could use this. Save you getting out of bed to turn the light out.’

The thing she held resembled no lamp she had seen before. It had a spaceship sphere aboard a reedy little stem which bent according to the desired angle.

Esme plugged into the wall. ‘Well, it works.’

‘It’s horrid, I know, but I thought we could nip out and buy a few things to brighten the place up.’

‘There’s not much point. I’m going to be sleeping here for such a short time and I’ll bring more stuff from Scotland once I’ve found somewhere permanent to live.’

Esme began the sentence to cover for having no money and then realized it was in fact true. And if she did end up staying here longer than planned, she may not have cash to splash but she knew she could ‘borrow’ some bits and pieces from her father’s business. Surplus furniture and objects from her parents’ former London home sat in profuse quantity at a warehouse in Peckham along with the countless shelves of antiques and collectables he was supposed to be selling on. Their London house in Pelham Place was the only one of her parents’ assets that her father had been willing to relinquish to pay for the school fees, domestic bills at The Lodge and his continued antique collecting. He had more than enough furniture and artwork to stock ten houses but flatly refused to put any of them up for auction saying they would always increase in value. He was a hoarder not through necessity but possessiveness and not a little pride. He liked being known for his brilliant eye and had to continue his charade with dealers that he was still flush with cash.

Esme had been ‘Christmas shopping’ at the warehouse a few times with her mother, who filched presents for her sisters and godchildren. ‘Daddy won’t notice, darling. He bought one chandelier only to buy an identical one a week later. He doesn’t care what he buys, just so long as he is spending. Far better to give these pretty things a happy home.’ Esme had seen the sad look in her mother’s eyes and realized she too was one of the pretty things left to linger unseen and unloved – little wonder she’d sought solace with the Earl.

Norman the warehouse manager was, like so many men, half in love with her mother. He had worked in the storage depot – part of the Munroe family business – for years. The warehouse and affiliated fine art transportation company housed and moved works all over the world. Her father joked that the humidity- and temperature-controlled Munroe lorries would keep a body in perfect condition for decades. If Diana decided she wanted a Raphael in holding for the National Gallery, Norman would have turned a blind eye as she popped it into the boot of her car. He adored Esme too, so surely having a few bits on loan would be no problem.

When she’d finished unpacking, she went back downstairs to set to work. The phone didn’t stop ringing from the moment she sat down. Unfamiliar with the flashing extension buttons she’d cut the first caller off.

‘Cartwright,’ she said as she’d tried again.

‘What happened?’ said a strong accent. ‘Is Bill there?’

‘I’m so sorry,’ apologized Esme, grateful the caller couldn’t see her blush. ‘I’m afraid not. May I take a message?’

‘It’s Serge. I’ve got news on the Claude.’

Esme scribbled his name and the time. It was ten thirty and a stack of messages had already built up.

‘May I take a surname?’

‘Très amusant, Suki…’

‘It’s not Suki. My Name is Esme. I’ve just stated working here.’

‘Ah. OK. If you could ask Bill to ring. Etienne is my surname.’

Esme reckoned she spoke to six different accents from around the world that first morning. Each individual must have been a multi-millionaire, considering the easy way they spoke about snapping up masterpieces and artists that commanded hundreds of thousands of pounds on their price tags. At one point there were three customers holding on the line and she felt like queen bee of a hive she had no control over. It wasn’t till noon that things calmed down and she was able to leave her desk.

‘Esme?’ shouted Suki.

‘Hang on, I’m just on the loo. Haven’t been since I arrived,’ she yelled back.

‘I’m coming up. It’s nearly one o’clock. Shall we grab some lunch?’ said Suki, a little breathless after the stairs.

‘Yes. I feel faint with hunger,’ said Esme, hanging a dress behind the door.

‘Let’s see that.’

Suki held up a floral printed frock.

‘Oh my God, Esme. You can’t possibly wear that. It’s so dated. Fine for tea with the vicar’s wife but not for London. Bill will have a coronary if he sees you in this sack. Fire you on the spot. We better go shopping at the weekend. I’ll bring some things of mine in until then. We’re about the same size.’

‘What’s wrong with it? I got it from Laura Ashley.’

‘Exactly,’ said Suki, tossing it on the bed. ‘Come on. We better go out now as we have to be back by two. You can wear my coat.’

Suki set the gallery alarm and locked the door.

Jermyn Street had filled up. A mass lunchtime exodus of office workers and gallery owners. They looked like pupils leaving school all in a uniform similar to Suki’s. A gaggle of big hair and navy blue. Esme was grateful for Suki’s mac.

The restaurant was a small Italian cliché, like the ones Esme had seen in films. Red-and-white check tablecloths and hurricane lanterns burning moodily despite it being the middle of the day. They were shown to a tiny table above which lopsided photographs littered the walls. A smell of thyme and wine wafted through the air. The Italian owner posed with friends in all of them. Esme recognized Francis Bacon in one and Michael Caine in another.

‘Do these people really come here?’ she asked Suki, pointing to another photo where the owner stood grinning next to Bill Wyman.

‘Not so much at lunchtime but during Wimbledon all the tennis players come here. Look. There’s Vitas Gerulaitis and I saw Roscoe Tanner in here once. Did you know his serves reach over 150 mph, 153 actually?’

‘Wow,’ said Esme, having no idea who the girl was talking about.

‘He’s divine too. So, handsome in a preppy kind of way,’ she dug her grissini in the butter.

Esme did the same. If there was one thing she would never be able to give up, it was butter.

‘I love it, don’t you? Specially this cheap salty stuff.’

‘What do you mean cheap?’ said a deep Italian voice. ‘Lorenzo!’ shrieked Suki.

It was the man in the photographs.

‘Ciao, bella!’ bellowed Lorenzo giving Suki a double kiss. ‘And who is this?’ The grey hedgehog-haired man with a matching beard looked at her with kind eyes and a big smile.

‘Lorenzo, this is Esme. It’s her first day at the gallery. She’s Bill’s goddaughter.’

‘Well, my sister is. Nice to meet you, Lorenzo.’

The proprietor took her hand, kissed it then stroked her face in a paternal way.

‘Bellisima signorina. Welcome to my humble ristorante. I am at your service.’ Esme flushed.

‘What’s the special today?’ asked Suki.

‘Lasagne, amore. It’s always LASAGNE! Food of the working man… and woman.’

Lorenzo winked at Esme. ‘You like?’

‘That would be lovely.’

‘I’ll have tomato, mozzarella and avocado, please, Lorenzo.

With extra basil.’

‘Perfezionare. And to drink I’ll bring you peach bellini. On the house, to celebrate Esme.’

‘Are the white peaches in yet?’ Turning to Esme, Suki was almost dribbling as she described the pale fruit with a pink blush that Lorenzo got sent from his farm in Calabria. ‘It’s hotter there so they ripen earlier.’

Lorenzo reappeared with the said fruit cut into slices, then proceeded to mash them up with a fork. Juice seeped from the flesh. Using his hand to dam the pulp, he poured the nectar into two champagne glasses and topped them up with sparkling wine. It was a far cry from the Buck’s Fizz concoctions Esme had tasted before.

‘Oh my God! This is literally the best thing I have ever tasted.’

‘Isn’t it?’

The sweetness of the peaches coated her tongue as the alcohol hit her empty stomach with a tide of reassurance.

‘So,’ said Suki. ‘Tell me more. Which school did you go to?’

Esme wiped the froth from her upper lip. ‘St Anne’s in Glamorgan. A convent run by sadistic nuns. I hated it.’

‘Oh, I loved mine.’

You would, thought Esme. She imagined Suki was the kind of jolly hockey sticks Hooray Henrietta who had been sent away at six years old and developed the stoicism of a Land Girl. Had this been the nineteenth century, she would have had skin thick enough to thrive in some far-flung British colony. But Esme admired her forthright approach. And she was kind and not only interested in herself.

‘How old are you? Actually, let me guess. Twenty? I’m twenty-four and you look way younger than me but maybe it’s the bumpkin clothes you are wearing.’

‘Oi! I’m twenty-two and I’ll thank you to know that my jeans are from Fiorucci. My sister will kill me when she realizes I’ve borrowed them.’

‘The jeans are OK. It’s the sweater that lets you down. I’ve kept mine for my children.’

Esme knew her sweater was dated and regretted wearing it. She desperately wanted a new image, one that was cooler and less Highlands or Home Counties, the two categories all her clothes currently fell into.

‘I know and as soon as I get my first paycheque I am going shopping.’

‘And I’m coming with you,’ said Suki.

The kitchen doors swung open as Lorenzo came through them backwards carrying a double draw of plates.

‘There you go, my ladies. Your lunch.’

Esme had to ask three people directions to Bill’s road that evening. Tucked away near the American Embassy, the little mews house had a chic exterior with glossy black door standing stark against the white façade. A pair of box trees flanked the entrance. She rang the bell. From inside she heard a high-pitched, ‘I’m coming, Esmeee.’ Must be Javier, she thought. Then an equally shrill bark followed.

The door flung open and out rushed a squeaking, clipped Shih Tzu. Framed in the doorway was a man standing barefoot and in what appeared to be nothing more an apron with the words ‘Choke n Puke’ printed on the front. His olive skin gleamed and smelt of sandalwood and citrus.

‘At last. The famous Esme. I’m Javier. But you probably worked that out. Come in. Come in.’ He looked her up and down, making a not altogether positive evaluation, judging by his arched eyebrows.

‘Let me take your… um… coat,’ he said, pulling it off her shoulders and discarding it on a chair with two fingers, like it was contaminated. So much for Suki’s taste in clothes, thought Esme.

Javier had an American accent, with musical undertones. Spanish or Portuguese, she guessed. His slick black hair was salted with grey flecks that grew in density on his unshaven chin. The deep furrows on his forehead served as guttering to prevent sweat running into his eyes and his rugged good looks gave him a kind of sexual magnetism that she imagined all ages and genders would find hard to resist. Her parents had never mentioned Bill’s boyfriend but clearly he knew all about her.

‘It’s divine to meet you finally. Bill isn’t back from his meeting yet. Work, work, work. That’s all he does while little Javier cooks, cleans and fucks. A whore in the bedroom and goddess in the kitchen. That’s what all men want, darling Esme.’

Esme laughed. She liked him at once.

Music blared, an echo that was trapped and condensed by the marble hallway. Unlike his gallery, Bill’s house was monochrome and modern. Black, white and grey created a cool atmosphere that was masculine and immaculate. Not a thing was out of place. Everything was perfectly arranged with precise symmetry and unpretentious good taste. A huge black-and-white image of an orchid hung above the hall table. Powerful in its stark simplicity, it was one of the most beautiful photographs Esme had seen.

‘Wow. This is stunning,’ she said.

‘My friend, Robert Mapplethorpe. Bill collects him. He’s photographed both your parents, you know. I met Diane the Divine and your handsome father many times. Adore them both…’

The sentence was interrupted by the ecstatic barking.

‘Bill is here. Tinky recognizes the engine, don’t you, clever girl?’ said Javier, giving her a pat. Tinky was hypnotized by the door, too focused on keys in the lock to react. She sat ears cocked, whining, her little body shivering.

‘Sorry I’m late, darling.’ Bill said, pecking Javier on the cheek and gently kicking Tinky out of his path before hugging Esme.

‘You found us no problem?’

‘I got a bit lost. I never knew this street existed nor did my A-Z. It’s not on the map.’

‘Don’t you love that? It’s like we don’t exist. Our hidden gem.’

Bill put his arm around Javier.

‘I see you have put some underpants on in honour of Esme’s arrival.’ And then to Esme, ‘You are lucky. Or unlucky. Depending on your broadmindedness, he normally wanders the house starkers.’

‘Oh, don’t worry. I’ve seen it all before,’ lied Esme.

She wasn’t accustomed to such open displays of emotion and she didn’t want to appear gauche.

‘Toots, do you need any help?’

‘No. Give the girl a drink, please. I’ve made pisco sour. Ice in the bucket. I couldn’t find limes, I’m afraid so it’s lemons.’

‘Delicious. Have you had pisco before, Esme, darling?’

‘Is it a cocktail?’

‘Yes, from South America. Like Javier. He whooshed into New York from Puerto Rico. Sit down, darling.’

Esme did as bid and sat on a stylish but uncomfortable sofa. The west-facing windows captured the evening sun, stealing the contrast from her vision. She shaded her eyes from the light to get a better look at the first-floor drawing room; a highly polished oak floor and an Aubusson rug in almost pristine condition. A low glass table was stacked with coffee table books and three ashtrays, although neither Bill nor Javier appeared to smoke. An enormous arrangement of freshly cut flowers filled a Chinese vase confusing a fat bumblebee collecting pollen from one of the blooms. Another photograph hung above the fireplace, a portrait of a messy-haired woman with a big nose and intense stare.

‘Patti Smith. Beautifully ugly,’ Bill said.

‘The singer?’

‘Yes. Amazing woman. Super bright and with a highly evolved sense of rebellious creativity.’

‘Do you know her?’

‘I do. Give me a writer, singer, artist any day over the upper classes. Don’t get me wrong, there are – like everything – exceptions to the rule but most of them are bores and their offspring messed-up wastrels. Look at your friend, Lexi. Did you see the way she threw herself on Henry’s coffin?’

The hideous scene was one no one would forget. As the Earl was being lowered into his grave, Lexi, sobbing hysterically, tried to join her father. It would have been heart-wrenching were it not so melodramatic. This attention-seeking drama had astonished Esme, but she went to comfort her friend, nonetheless. As had been the case ever since they had gone to different boarding schools, her kindness was rejected. As children, they had been more than friends and closer than sisters, pledging eternal love and comfort through thick and thin. Their bond had seemed unbreakable but returning from her first term away, Lexi had changed. She was cold and snipey – like an ex-girlfriend. Esme was confused and hurt but Sophia told her to move on. ‘She’s jealous of you, Es,’ she had said. But Esme, grieving for the friendship, was unable to imagine a single reason for that jealousy.

‘I know she adored her father to the point of obsession, but really it was beyond the pale. We are all devastated and no one more than your dear mother. Now she really loved Henry, unlike that ghastly wife of his.’

It had been the perfect day for a funeral. Cold, grey and drizzly. Hundreds of people had turned up to the service at Sellington Church, from the great and the royal to tenant farmers whose families had worked on the estate for generations. It was probably why she hadn’t spotted Bill among the mourners. That and the fact she’d been too busy keeping an eye on her mother. Diana, composed but withdrawn, stood regally like a head of state. It had been a long time since Esme had witnessed the kind of self-possession her mother held that day. Almost as if she wanted the Earl to be proud of her. A quiet ‘Goodbye, my love,’ heard only by Esme, were the last articulate words she said.

All through her childhood, covering for her mother had been second nature to Esme, and only now, finally an adult herself, did she see how much it had cost her in tears, loneliness and confusion. Whilst it upset Esme that her mother was now in an institution, and that she couldn’t visit as often as she would like, she knew that she was in the best place and cared for in the way she had needed for a long, long time.

Her mother’s decline had been rapid after the Earl’s death. Whilst she still possessed a ghostly beauty, it was now like a sapped peach deprived of sun. Esme’s father could no longer cope and despite Mrs Bee and Esme and to a lesser degree Sophia’s objection, he had elected to send her to a local care home. Esme had wanted her to stay at home and hire a carer but the Munroe funds didn’t stretch to that, thanks to her father’s continued extravagant antique collecting. Esme often felt like her mother had been one of his greatest acquisitions. Beautiful, brilliant and funny, she’d shone brighter than any of her father’s ornate vases or diamond brooches. But, as time went by, her cracks had begun to show.

‘You know Mum is…’ she faltered over the words, fearing Bill would judge her ‘…in a home now?’

‘No, I didn’t but it doesn’t surprise me, darling. She has been ill for so long and your poor father has been on the end of it. To be honest I think he was quite relieved that Henry took her off his hands and now he can enjoy himself without the guilt.’

‘But to send her away like a retired greyhound? Talk about death in the fast lane. He might as well have put a bullet in her head.’

The words just tumbled out – she’d barely even acknowledged to herself that that was how she felt. She’d been too busy putting on a brave face. But now, here on her own in London, she could let rip. She felt a wave of gratitude for Bill – he knew all the people in her family and their circle, yet somehow had escaped their rules and suffocating expectations. After so many years of hidden meanings and things unsaid, his directness was wonderfully refreshing.

‘I imagine she doesn’t know where she is, dear girl. Most of the time, anyway. Terrible thing, manic depression when it’s as severe as hers. Nigh on impossible to manage at that level, and it really took its toll on your father, and you and your sister, I imagine.’

Esme was grateful that she remembered her mother before the illness took got a real grip when she was ten or so; before that she was up or down but never in between.

‘In truth, I feel like Mum died years ago but I’ve never lost hope that she might return. In her mind, I mean.’

‘It is so sad but you must remember she would be happy to know you are here making your own way in life. You were her favourite, you know.’

She did. And her sister’s jealousy had been made blatantly clear by years of persecution when they were young. Once Sophia got her first boyfriend, everything changed, though. They were now great friends and each other’s main source of support. With both parents notoriously unreliable, the girls had come to rely on each other.

‘And Sophia is Dad’s favourite. By the way, do you know who he’s staying with in France?’

‘Yes. Francis Burn.’

Of course it was Francis, thought Esme, the kaftan-wearing extrovert who loved antiques as much as her father.

‘He has an exquisite house near St Remy. Colin has always maintained the best light is to be found in the Alpilles… He and Cezanne both. Lovely place to spend the summer. I know your father needs to get away sometimes, take solace in his painting.’

Bill looked at the clock on the mantelpiece. ‘Let’s go down for dinner. We don’t want a tantrum.’

The house had a formal dining room, but they were to eat in the kitchen, being just the three of them. Javier had replaced the apron with a flamingo-pink shirt and pale-blue trousers. He was a beautiful man. There was a clarity about him. The sharp relief of his features and the brilliance of his eyes made him cry out to be put on show and admired.

The kitchen table was set for three courses. Esme sat between the two men. She shook her napkin and laid it on her lap.

‘It maybe a kitchen supper but we never drop standards here,’ laughed Bill. ‘I only write thank you letters to a hostess who uses real napkins that need to be washed and ironed. It is the surest sign of respect for their guests.’

Esme made a mental note.

The first course was a fishy mousse with diced tomato and cucumber dressed in oil and lemon juice with buttered brown bread cut into triangles. Javier sprinkled a bright red sauce over his starter. ‘Careful, it’s very spicy,’ he warned. ‘Like me—’

‘Like you,’ Bill and Javier said in unison, taking each other’s hand.

The affectionate bickering and bitching that ping-ponged between the two was a refreshing relief to the stony silence she was used to at the dining table at home. Esme couldn’t remember the last time she had laughed so much. There was no sense the couple were putting on a show by being on best behaviour for public eyes. This relationship was genuine and made her feel completely at home. Warming to their outrageous indiscretions, Esme found herself matching their gossip with stories of her own. She told of the time the Contessa had tried to kill her dog by locking him out on the castle terrace in the sub-zero winter of 1969. And how Princess Margaret had asked her to collect a knife when they had gone to powder their noses at the Culcairn Hunt Ball.

‘A knife?’ said Bill.

‘Yes. She put it in the loo and started chopping. “It simply won’t go down,” she said.’

The two men – or the Boys as she now thought of them – howled with laughter. ‘That is the funniest thing I have ever heard!’ said Javier. ‘They always say think of the Queen on the toilet—’

‘Loo, Toots—’ Bill gently corrected Javier.

‘—on the loo when you’re nervous. But this! I will never get stage fright again.’