Полная версия

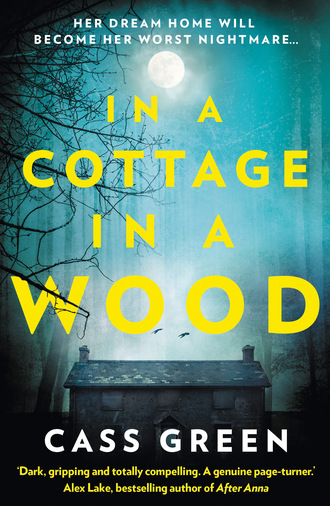

In a Cottage In a Wood

Neve sighs and entertains the possibility of hanging up. But no, she needs to see this through.

Eventually a different woman comes to the phone. She sounds a little warmer.

‘Hello, you were asking about the suicide from Waterloo Bridge on December twenty-first?’ she says.

‘Yes, that’s right.’ Neve’s heart speeds up and she finds herself clutching the receiver, her hand damp. There’s a pause.

‘I’m afraid a body was found the following morning.’

‘Oh …’ Neve puffs out the word in a sigh. She didn’t know what else she had been expecting, but the news still feels electric and cold in her stomach.

‘Did you know the individual?’ the woman continues brightly.

‘Well, no, I was just there. You see …’

She finds herself recounting the whole thing again, while the woman on the other end of the phone clucks, ‘Oh dear’ and ‘What a shame,’ at key points.

When she has finished, the woman lowers her voice a fraction before speaking again. ‘Look,’ she says. ‘It’s very common in these situations to feel guilty and think you could have done something. But put it this way, this was someone who was serious.’

‘What do you mean?’ says Neve, sitting forward in her chair.

‘Well,’ there’s a pause, ‘she made certain provisions to make sure she sank quickly.’

Neve quickly scans her memories of what the woman, Isabelle, had looked like. There was no coat that could be filled with stones, à la Virginia Woolf. She wasn’t carrying anything. So how on earth did she weigh herself down enough to drown? She pictures that silky dress, clinging to Isabelle’s thin frame. The swishiness of it and the jarring sense that it was from another, more glamorous time.

‘I just don’t get it,’ she says miserably. ‘She was only wearing an evening dress.’

There’s a brief silence and then the woman speaks all in a rush. ‘Look, I’m not sure whether I ought to release this information without the family’s permission but you were the one who had to see it all so, well …’

She clears her throat and lowers her voice further. ‘It was the hem of her dress, you see,’ she says. ‘She’d sewed lead curtain tape all around the bottom of it. This was enough extra weight for someone of that size to sink.’

Neve’s stomach lurches. ‘Oh God,’ she says. ‘That’s awful.’

‘Yes, it’s terrible,’ says the woman. ‘She had obviously done her homework. In that stretch of the Thames, most people are rescued before there’s any prospect of drowning, you see. Such a shame. She really meant business, the poor thing.’

7

‘No more for me, thanks Stephen.’ Steve’s mother Celia puts a small, neat hand, tipped with shell-pink polish, on top of her glass of wine. She has been nursing the same glass for the last two hours.

Her husband Bill is engaging their son in a lengthy discussion about the shortcomings of the M4 and the A406. This is a follow-on from the same conversation earlier.

Steve nods and is trying to look interested, while simultaneously shooting looks at his small daughter, who is sitting with a mutinous expression on her face. Lottie has been recently reprimanded by her grandmother for whining and looks ready to blow at any moment.

They are sitting at the table with the wreckage of Christmas dinner in front of them. The gold tablecloth is a battleground of spilled peas, which Lottie had refused to eat, rings from glasses and small lumpy mounds of red wax from the festive candle that is melting like a squashed volcano in the middle of the table.

Neve stifles a yawn.

Today seems to have been going on for an eternity. At five a.m. she was woken from a dream about Daniel by the study door opening and the sound of feet padding across the floorboards.

She’d kept her eyes firmly closed, then felt laboured breathing hot on her cheek. After a moment Lottie had announced in a stage whisper that, ‘Mummy and Daddy say it is too early to see if Santa has been.’

‘That’s because it is too early,’ Neve had groggily replied. Then, when Lottie showed no sign of going back to bed, ‘Why don’t you go and have a look on your own?’

She hadn’t even been aware, really, of what she was saying; she’d only wanted Lottie to go away. And she certainly didn’t remember saying, ‘Yes, you definitely are allowed to get started on the presents,’ as was later claimed by the little curly-haired Judas.

But it turned out she had committed a crime of major proportions an hour later when she heard raised voices from the sitting room.

Lottie had gaily skipped away and unwrapped everything under the tree, including everyone else’s gifts. She had eaten a whole selection box and was starting on the handmade Belgian chocolates meant for her grandma before anyone else got up.

Lou had been tearful because a special moment – when the family all discovered the presents together – had been ruined. She had been planning to film the whole thing. Lou was, in Neve’s opinion, an obsessive chronicler of her family life. She would have unfollowed her sister on Facebook because of this, had she been able to get away with it.

Steve, surveying his guilty-faced daughter, and the colourful piles of ripped paper, wore an expression that wasn’t at all Christian. Neve was in the doghouse.

He spent the rest of the morning cooking and refused all offers of help, while retaining a beleaguered air.

Lou has been brittle with tension all day. She doesn’t like Celia and Bill, Neve knows this. But she seems to think that if she refrains from criticizing them, even to Neve, then she will somehow find a deeper reservoir of tolerance.

Neve has resolved to be the model guest for the rest of the day. When Bill resorts to one of his favourite topics of conversation – namely, the fact that the ‘UK is an island with limited resources and it’s time something was done about our border controls’ – Neve smiles sweetly and suggests she clear the table and wash up.

Celia regards her as she hands over her smeared plate.

‘So how is the flat hunting going, Neve?’ she says. Neve hears Lou quietly sigh.

‘Bit slowly,’ she says with a small laugh. ‘Everywhere is so expensive. But I am looking!’ She sets her jaw as she picks up more plates, hoping for a quick exit from this conversation. But Celia isn’t finished.

‘Have you ever thought about moving back to your home town?’ she says. ‘Do you have any people there? Remind me. I mean,’ she adds, hurriedly, ‘I know you don’t have your mum and dad any more, but is there anyone else? Wider family?’

Lou shoots her a panicked look. Celia knows full well that Lou and Neve are the only ones left. Steve has two siblings with five children between them, several aunts and uncles, and his grandparents only died in the last couple of years. He’s positively rotten with family, thinks Neve. He has no idea what it is like to be an island that only contains two, yet is still somehow crowded.

She feels a sharp tug of love for her sister now and the urge to say something shocking and untrue, like, ‘No one that isn’t inside,’ but knows her sister will be even more upset with her.

Neve decides to ignore the question.

‘Shall I make you some tea, when I’m done washing up?’

Wrong-footed, Celia blinks at her without replying.

Neve’s phone buzzes in her pocket then and, despite herself, she can’t resist sliding it out and glancing at the screen.

It’s from Miri and says simply SHOOT ME NOW. Neve smiles weakly.

Lou is watching her with a similar expression to the one she keeps flicking towards her eldest daughter. Neve knows that her sister is wondering, constantly, about whether she is in communication with Daniel. Neve decides to put her out of her misery.

‘Miri says hi,’ she says.

Bill seems to wake up at this. ‘Miri. Now that’s an unusual name. English girl, is she?’

‘Yes,’ says Neve as she heads towards the kitchen. ‘Her full name is Amira Sharma-Kapoor.’ She looks back over her shoulder and adds, ‘She was born in Croydon.’

At the sink she can’t stop the grin at the silence in her wake. She can picture Bill and Celia exchanging glances. She attacks the washing up with fast efficiency, hoping that no one will offer to help her.

Bill and Celia retire to the sofa now and Celia is tasked with trying to put batteries into one of the few plastic toys Lottie has been allowed to have. Everything else has a wooden, utilitarian air about it and screams ‘educational’. Neve had played it safe and stuck to the present she was instructed to buy; a stacking game with colourful wooden balls which Lottie hasn’t looked at since opening.

Maisie starts to grizzle and Lou takes her off into another room. She still occasionally breastfeeds her and knows she will get a frosty reception from Celia, who once declared that there was ‘no need for letting everything hang out’. Neve, having seen what having two children has done to Lou’s breasts, guiltily half agrees with this sentiment.

As she washes up, Neve thinks back to the Christmas before. She and Daniel, who didn’t speak to his parents any more and was without familial ties, had holed up with wine, beer and a range of deli food from Marks and Spencer. They watched Breaking Bad in one long marathon, stopping only for sex and food breaks. There was no tree and they sent no cards.

It had been her best adult Christmas.

Her heart feels sand-bag heavy inside her chest as she remembers them emerging, blinking into the daylight for a walk on Boxing Day. They’d walked hand in hand on Hampstead Heath and stopped for hot chocolates in the funny old café that never seemed to change.

It’s hard to think about what they talked of now.

So much of their time together – almost four years – had revolved around going out, getting stoned, getting drunk. Laughter. Music. Sex.

Fun.

During his ‘up’ times anyway. There were other periods when Daniel turned his face to the wall for whole mornings or afternoons and was monosyllabic. She used to tell herself it was all part of his arty personality and that his up and down moods were somehow fuelled by creativity.

Daniel was a musician, who played in a couple of bands and also did the occasional bit of session work, mainly classical guitar. He was a few years older than Neve – thirty-six on his last birthday. When, shortly after, he had quit both the bands on the same weekend, she’d told him he was having an early mid-life crisis. Then he took off, to Ireland, to visit a friend, so he said.

And while he was away, she was so angry with him that she got drunk and slept with his friend and band mate Ash. When he came back it turned out he had been ‘trying to get his head together’ and had decided it was time they got married. Neve didn’t want to get married. But she didn’t want him to know about Ash either and she had ended up blurting that out within two hours of him getting home.

She’d moved out a few days later. There’s no prospect of being forgiven. Daniel was ‘betrayed’, as he put it, by his first love and had sunk into a deep depression after this. Now, he says Neve has opened up old wounds, and inflicted new ones.

She still doesn’t want to marry him. But she wishes they could slip back into their old life and just carry on as they were. Why did things have to change?

Taking a tray of teas and coffees into the living room, Neve sees that Lottie has built a teetering tower out of her building blocks and is concentrating with a scrunched brow and chewed lower lip on getting the final piece on top. Steve is helping and Celia is sitting close by and handing over marbles.

But as the final one is put into place, the whole thing collapses and scatters coloured glass in a surprisingly wide arc.

Lottie gives a frustrated squeal and says in a clear, bright voice, ‘Buggering cunty bollocks,’ just as Lou walks back into the room.

Celia sucks in her breath. Steve glares at Neve. Lou looks as though she is going to burst into tears.

‘Where on earth has she learned language like that?’ says Celia.

‘That’s what Aunty Neve said when she stubbed her toe on Daddy’s bike,’ says Lottie, eyes bright, picking up on the charged atmosphere. Neve forces a laugh and reaches for a cup of coffee. She takes a sip and scalds her mouth.

‘Oops!’ she says and glances around the room at the looks of disapproval and disappointment. ‘Sorry. I promise to rein it in.’

‘Yes, why don’t you?’ says Steve, furiously snatching up bricks. ‘Why don’t you just do that?’

Neve suddenly feels an overwhelming exhaustion wash over her. She would happily lay her head down on the carpet and sleep right now.

‘I said I’m sorry,’ she says in a small voice.

‘But are you?’ Steve’s face is rigid and Neve experiences a jolt at how much dislike she sees there.

‘Er. Yes, I am?’

‘Because,’ says Steve, ‘I don’t know.’ He gets to his feet. It is actually possible to see his internal temperature rising. ‘It seems to me as though you get a bit of a kick out of disrupting things.’

Injustice flashes bright inside her chest. ‘That’s not fair.’

Lou says, ‘Steve,’ warningly.

But Steve is only just starting. Lottie creeps towards her grandmother’s legs and leans against her, thumb in mouth and eyes wide.

‘No, Lou, you know that you feel the same way. You said it would be for a week or so and how long have you been here now, Neve?’

‘I’m not sure, maybe a month, but I’m trying—’

‘Six weeks,’ he cuts across her. ‘And not only do you leave a trail of destruction everywhere you go, you come in at all hours after doing God knows what. It’s like you think you live in a student squat, rather than a family house.’

‘Steve, please!’ snaps Lou. ‘It’s Christmas Day! This isn’t the time for that conversation.’

‘It never is the time!’ Steve’s roar shocks everyone, including, it seems, himself. He snaps his jaw shut and blinks furiously.

Neve gets up from the seat. She can feel it building inside her, and she knows she should just leave now. Say nothing else.

She also knows she won’t do that.

‘But you’re not so perfect, are you?’ she says, with a half-smile.

Steve laughs. ‘What’s that supposed to mean?’

‘Well,’ says Neve, ‘I’ve noticed that it’s always Lou who does the donkey work with the girls. You somehow manage to go out with your mates and do all your wanky sports, don’t you? While my sister looks like one of the walking dead most of the time.’

‘Neve!’

‘Sorry, but it’s true.’

‘If you care so much about your sister, you could help out a bit, couldn’t you?’ barks Steve.

‘Really,’ says Celia now, her face pink with outrage. ‘I must say that you are being very ungrateful after everything my son … and daughter-in-law have done for you.’

Neve can’t help it. It literally slips out of her mouth, as involuntary as a cough or a belch. ‘Oh you can fuck off, Celia.’

Celia’s mouth drops open and it occurs to Neve she has never seen this happen quite so cartoonishly before.

‘How dare you speak to my wife that way!’ bellows Bill.

‘STOP IT!’ Lou bursts into tears and the sound sets off Maisie from her bedroom. Lou is almost panting, her fists clenched at the sides of her head. She looks just like Lottie for a moment.

Neve feels her anger dull and makes a move to touch her sister’s arm, alarmed. But Lou shakes her hand away as if it burns.

‘Just stop it, all of you.’ She looks at Neve, her eyes gleaming. Her expression is one of genuine puzzlement when she says, ‘Why do you have to spoil everything?’

8

Monday 12th March 1996

Dearest Granny,

Can I just say that everyone is really overreacting?

Look, I’ve always been funny about blood – you know that. Remember when Rich broke his nose playing rugby? And I fainted and gave myself concussion? Then there was the time Mummy cut her finger when I was little and I got all hysterical.

It’s what I do. Funny old Izzy, etc! Big drama queen. As Dad always says.

And this time there were what you call them – extenerating (???) circumstances. I hadn’t eaten my lunch and was about to come on, so I was a bit wobbly.

The stupid thing about it is that the paint didn’t even look that realistic, not really.

We were in art and because it was almost Halloween, people were telling silly stories and trying to scare each other. And Sasha Picket, who always has to be at the centre of EVERYTHING, thought it would be really funny to cover her hands and arms in red paint.

She let out this horrible shriek and when we looked at her, her eyes were all wide and mad.

Everyone says that almost straight away she went, ‘Out, out damned Spot!’ and then cracked up. But I don’t really remember any of that.

All I know is that everything went tight and hot and there was no air. I wanted to make myself really small. I don’t remember screaming like they all said I did. I think they’re exaggerating about that part.

But anyway of course there was a big hoohah about it and all the teachers went nuts.

I am FINE.

F.I.N.E.

Okay? Promise!

So you can stop worrying about me. I hate school, but there’s nothing new there.

Can’t wait to see you and to give you and Bruce the biggest cuddles. Tell him I’m taking him for walkies SOON! Hope he’s being a good boy.

All my love,

Izzy xxxxx

I miss Mummy so much. She never went off the deep end like Dad does. I know you miss her too xxxx

9

January crawls along with skies the colour of cement and unseasonable temperatures. Sad little patches of bright daffodils break out in the parks and are largely ignored, like early party-goers. No one feels they have earned these signs of spring yet.

It all adds to a sense in Neve that everything is off kilter. She has been thinking about the woman, Isabelle, a lot. One night she even found herself contemplating calling the Samaritans. Not because she is depressed – she knows that a general feeling of my-life-is-shit-right-now is on a different continent to real mental illness – but because she thought maybe someone could explain to her what kind of thoughts were going through Isabelle’s head that night.

She keeps trying to step inside that moment again, when Isabelle spoke into her ear with that harsh whisper. Could she, Neve, have grabbed hold of her and stopped her doing what she did?

Could she have been kinder when she saw her there?

Every time she thinks about how irritated she had been at the hold-up to her journey home, she feels a nauseous lurch of guilt in her stomach. If only she had a bit more information. She forgot the woman’s surname as soon as the police had revealed it. Why didn’t she make a note of it somewhere? And how could she have forgotten? This feels like a terrible thing.

They have reached an uneasy truce at the flat. She has apologized, and so has Steve, but they both know their only regret is having upset Lou.

Lottie and Lou and the baby have all been felled by a vicious cold. Neve has the constitution of an ox but can feel a general sniffly misery pulling at her senses and knows it’s only a matter of time before she gets sick too.

At least she might get a day off work.

Miri is on maternity leave now and Neve is keenly aware of the space she has left behind. Two of her closest friends have moved away from London in the last year, both because they have married and started reproducing. There are invitations to go to Wales and to Sussex, or wherever it was, to visit, but she feels curiously dispirited by the prospect of admiring their wood burners and their big gardens and hearing all about how they ‘should have done this years ago’.

This particular morning has crept by with soupy slowness. There is an uneasy feeling at PCC because of a rumour that a German magazine company based in Beckenham are interested in buying the company and merging it with one that specializes in magazine part-works.

Neve has finished up all the jobs she has been asked to do this morning and now sits staring down at Facebook on her phone and giving desultory swipes at various posts.

She remembers that she had stuffed some letters into her bag this morning before leaving for work. A small pile was building up on the table and she knew Steve was going to start getting all twitchy about it soon, so she had resolved to take it to work to read and dump, depending on what it was.

Flicking through now she finds a couple of bills, an interesting-looking letter in a white envelope, which turns out to be from an estate agent of all things, and finally she opens an A3 brown envelope, knowing it is bound to be something to do with tax, or National Insurance, or some other unpleasantness.

But inside, she is surprised to see first a compliment slip with ‘Met Police’ printed at the top and a couple of sentences scrawled in blue Biro beneath.

Ms Carey, we were asked to pass on this information. Kind regards.

There is no signature.

Neve flicks the switchboard over to automatic and feels her heartbeat kick faster as she unclips the compliment slip and looks at the letter beneath.

The paper is thick and creamy; official-looking. The letterhead says ‘Beswick, Robinson, Carter, Meade, Solicitors and Commissioners of Oaths’.

The address is in Salisbury.

Neve quickly unfolds the letter, ignoring the lights that have started to flash insistently on the switchboard.

Dear Ms Carey

We have been instructed to act on behalf of trustees of the will of Miss Isabelle Shawcross, who died on 21st December 2016.

We would be very grateful if you could ring the office and arrange a time to come in at your convenience to discuss a matter that relates to these instructions.

We look forward to hearing from you.

Yours sincerely,

L. Meade (Solicitor)

At first, all she feels is relief. Seeing the police logo, and then the solicitor’s header, she’d had a terrible feeling of having been found guilty of some crime she doesn’t remember committing. She stole a traffic cone, drunkenly, a couple of years ago and for a strange moment had been sure they were finally coming for her.

The switchboard is lit up like the flight deck of a 747 now so she forces herself to pick up the phone and start routing calls where they need to go. She isn’t concentrating and one caller comes back to switchboard, annoyed at being sent to the IT office, rather than the post room as they had requested.

All the while her mind buzzes with questions.

How did the solicitor’s firm get her name? The police, presumably. That was easy enough to answer. But why on earth did this solicitor want to see her?

It couldn’t be that she has been left something in her will, because they only met just before she died. Neve doesn’t know much about it, but she knows wills have to be signed and witnessed well in advance of someone’s death.

So what else can it be?

Realization dawns and she actually says, ‘Oh,’ out loud.

Of course. The family want to speak to her, as the last person to be with Isabelle. To thank her? Or to have a go at her? Why didn’t she stop her from jumping and so on. As if she hasn’t tortured herself with that thought enough.