Полная версия

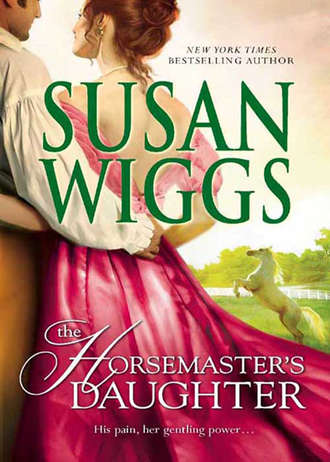

The Horsemaster's Daughter

Walking along the beach as if just taking a stroll, she completely disregarded both Hunter and the horse. The stallion turned at an angle, but Hunter could tell Finn was watching her with one wary eye. She continued walking, elaborately and disdainfully ignoring him. Like an inquisitive child, the stallion sidled closer.

Hunter’s fist closed around the makeshift club. Instinct told him to act quickly, spook the horse, but he forced himself to stay still. And watchful.

The horse moved closer and closer, inexorably drawn to the woman walking along the empty beach. Hunter could relate to that level of curiosity even as the tension churned in his gut. He tried not to think about the hired groom almost fainting from the pain in his shattered wrist.

The horse closed in near her shoulder. She sent Hunter the swiftest of looks, warning him not to interfere. His muscles quivered with the urge to act.

Eliza turned, quite calmly, and made a shooing motion with the rope. Snakelike, the rope sailed through the air and dropped on the sand. The horse immediately shied back, pawing the sand and dipping his head in irritation.

But he didn’t spook the way he had when Hunter had run at him. He wondered why Eliza would do that with the rope. Why provoke a dangerous animal? What was she thinking?

She continued walking, unconcerned. She reached a tall brake of reeds where the sand disappeared into the spongy estuary leading to the marsh. Making a wide turn, she headed back the way she had come, staying on the beach. To Hunter’s surprise, the horse followed her, though he gave her a wide berth.

After a few minutes, the stallion approached her obliquely again, and again she shooed him away, flicking the rope in his direction. She behaved like an exasperated mother flapping her apron at a wayward child. And like the wayward child, the horse never did lose interest, but kept trying to move in closer. They repeated the bizarre exchange several times more, always with the same result.

Then, with her shoulders square and her eye fixed on the horse, she moved abruptly toward the stallion.

Her motion alarmed Hunter. He took a step forward, then remembered his promise and made himself stop. Finn cantered in a tight loop, his attention fixed on her. Hunter expected him to disappear, but instead, he loped around and came back again. She kept pushing, taunting, startling him into flight over and over again. She never looked away from the horse, and the horse never looked away from her. It was an intricate dance of aggression and surrender, the partners intent on one another. The fascination was mutual.

Hunter kept expecting her to call for help, because the horse had moved in too close for comfort. Then he realized, with a start, that Eliza was controlling the situation completely. She dictated when the horse could come near, and when she wanted him to flee. There had to be a point to her actions but he couldn’t quite decide what that point was. She had the posture of ritual—the fierce attention of her stare, the dignified stance of her body, the solemn flick of her arm shooing him away.

After a few minutes, her gaze underwent a subtle change. Rather than staring so intently into the horse’s eyes, she looked away once. Then twice, thrice. The horse’s cantering slowed. It flicked back one ear. Still he feinted, but the loops he ran were tighter; he came back more readily. His head dropped a little, and Hunter could see his jaw working.

Each time the stallion approached her, he became bolder. Each time she shooed him away, he came back again. To Hunter, it resembled a subtle flirtation of sorts. She was clearly interested, yet full of disdain. The stallion played the ardent suitor, persistent, refusing to be put off, yet not gregarious enough to force himself on her. There was a curious grace in the interplay between girl and horse.

Perhaps she was stranger, even, than Hunter had originally thought.

Then, right before his eyes, the dance changed from a wary flirtation to a tentative partnership. The stallion stayed at her side now, his muzzle practically nudging her shoulder. They walked along side by side, their pace unhurried and their steps oddly synchronized, as if they were moving together to the same silent music.

Hunter started to relax a little. The horse perceived no threat from the woman, so he posed no menace to her. When Eliza Flyte turned, the stallion turned. When she quickened her pace, so did the horse. When she slowed down, he did the same. And finally, as if it were the most natural movement in the world, she stopped walking and touched the horse, her hand resting at the side of his head.

Hunter heard her whoa across the broad stretch of beach. The horse halted. Hunter froze, held his breath. He couldn’t have taken his eyes off her if he’d wanted to. But he didn’t want to. He was as much her prisoner as was the horse. Finn’s ears flickered but he didn’t pull back, and she didn’t take her hand away.

She turned her body toward the stallion, though she held her gaze faintly averted. He dropped his head, submitting with something almost like relief. His muzzle hung so low to the ground that he probably inhaled grains of sand into his nostrils. The pose of submission looked incongruous on the big horse.

The girl, like an angel, ran her hand down the length of the horse’s head. Even from a distance, Hunter could see the stallion’s shivered reaction to that gentle caress, and it had a strange impact on him. He felt Eliza’s hand on the horse as if she had touched him. It was absurd, but he found himself so captivated by her that he wanted that caress for himself.

It was an unorthodox way to train a stallion, one Hunter had read about in the writings of the great horsemaster, John Solomon Rarey. He had never thought the method could be put to practical use, but the mystical ritual had taken place before his eyes.

She had made the stallion want her—to be near her, to be touched by her.

Hunter lowered himself to the ground, looping his hands loosely around his drawn-up knee. He wondered what she would do next.

Just then, a flock of gulls rose as one from the shallows. Their wings flashed white against the sky and they made a sound like a gust of wind. The horse panicked, rearing so high that his hooves nearly struck Eliza in the head. Hunter roared out a warning, leaping up and running toward her.

She calmly stepped away. The horse landed heavily, then twisted his big body and galloped away toward the thicket behind the dunes.

“You’re crazier than the horse is,” Hunter said, his nerves in shreds. “I won’t have any part in this. I’m leaving with the morning tide.”

Eliza appeared not to hear him as she coiled the rope carefully. “That’s enough for today anyway,” she said. “There’s always tomorrow. Best not to rush.”

“You might not be able to find him tomorrow.”

She shaded her eyes and looked up at the rise of the dunes. The stallion turned, showing his profile, and reared against the sky, a whinny erupting from deep within him. Then, with a flick of his tail, he was gone.

“He’ll be back,” Eliza said.

Six

Eliza set out some of last autumn’s apples she’d preserved in a charcoal barrel. In the morning she slipped out early to find that they’d been eaten. She tried to quell a surge of excitement, reminding herself that her father’s first rule was to work at the horse’s pace, peeling away his fears layer by layer rather than trying to rush things. There were more good horses ruined by haste than by any sort of injury, she reminded herself.

In the half-light she inspected the training facility that had been the hub of her father’s life. It was sad, seeing it like this, broken, burnt and neglected. He had died here, she thought with a shudder. He had died for doing the precise thing she was about to do.

The area inside the pen was overgrown with thistle and cordgrass. She would have to spend the day clearing it. Backbreaking but necessary work. Perhaps Hunter Calhoun would be of some use after all.

The thought of her unexpected visitor seemed to have summoned him, for when she untied the halter and turned to pull the gate, he stood there, behind her.

He discomfited her. There was no other word for it. Wearing his own clothes rather than the ill-fitting ones he’d worn yesterday, he managed to appear as broad and comely as a storybook prince, with the breeze in his blond hair and his sleeves rolled back to reveal the dark sun-gold of his forearms. On closer inspection she saw that a golden bristle shaded his unshaven jaw, but that didn’t make him less striking. It only served to soften the edges of his finely made cheeks and jaw, and added to his appeal.

She had never heeded her own looks. She’d never taken the time to make sure her dress fit nicely or her hair was properly curled and pinned. Living on the island with her father, and lately all on her own, made such vanities seem unimportant.

But now, feeling the heat of this man’s stare upon her, appearances were everything. Absolutely everything. She wanted to shrivel down into the ground like a flower too long in the sun. She found herself remembering a group of gentry that had accompanied the drovers to the island to buy ponies from her father one year. They’d made a holiday of it, much as people did on penning day up at Chincoteague to the north. She was twelve, and until that day she had not known a girl wearing breeches and haphazardly cropped hair would be considered anything unusual.

But as she walked past the freshwater pond where the herd of ponies grazed, she became aware of a hush that swept over folks as she walked by, followed by a buzz of whispers when she passed.

“I never knew Henry Flyte had a boy,” someone said.

The dart had sunk deep into the tender flesh of her vanity. She recalled actually flinching, feeling the sting between her shoulder blades.

“That’s no boy,” someone else declared. “That’s the horsemaster’s daughter.”

That day, Eliza had stopped wearing trousers. She had painstakingly studied a tattered copy of Country Wives Budget to learn how to make a dress. She let her hair grow out and tried to style it in the manner of the engraved illustrations in the journal. In subsequent years, visitors to the island still whispered about her, but not because she looked like a boy. It was because she had become a creature recognizable as female no matter what she wore. The stares and whispers carried quite a different connotation. But she never managed to fix herself up quite right. Never managed to capture the polished prettiness of a girl gently raised. And in truth, it usually didn’t matter.

But when she brushed the tangle of black hair out of her eyes and looked across the field at Hunter Calhoun, it mattered.

“I was just thinking about you,” she confessed.

He propped an elbow on the rail and crossed one ankle over the other. “You were?”

“This area needs clearing.”

One side of his mouth slid upward. She couldn’t tell if it was a grin or a sneer. “And why would that make you think of me?” he asked.

A sneer, she decided. “Because it’s where your horse is going to be kept.”

“I told you yesterday, I want no part of this idiotic scheme. I plan to leave—”

“You’re not going to get away with just leaving him.” Her thoughts, of which he could have no inkling, made her testy. If he wondered why, she’d just let him wonder. “I didn’t ask you to bring him here, but now that you have, you’re going to see this through.”

He spread his hands in mock surrender. “It is through. Don’t you see that? The horse is vicious, and he’s scared of a flock of damn birds. Sure, you did a little parlor trick with him down on the beach, but you’ll never turn that animal into a racehorse.”

She glared at him. “Get a shovel.”

“I just said—”

“I heard what you said. Get a shovel, Calhoun. If I’m wrong, you can—” She broke off, undecided.

“I can what?”

“You can shoot me, not the horse.”

He laughed, but to her relief, he picked up a rusty shovel and hefted it over his shoulder. “You don’t mean that.”

“There’s one way to find out.”

“Damn, but you are a stubborn woman. What the hell gives you the idea you can turn this horse around?”

“I watched my father do it for years, and he taught me to do it on my own.”

“And just what is it you think you can do for that animal?”

“Figure out why he’s afraid, then show him he doesn’t need to be afraid anymore.” She eyed him critically. “It would help if you’d quit spooking him every time he twitches an ear.”

“If it’s so simple,” he asked, “why don’t all horsemen train by this method?”

“I don’t know any other horsemen,” she admitted. “My father showed me the ways of horses by taking me to see the wild ponies, season after season, year after year. If you watch close enough, you start seeing patterns in the way they act. As soon as you understand the patterns, you understand what they’re saying.”

“You claim to know a lot about horses, Eliza Flyte. Sounds like you gave it a fair amount of study.”

“It was my life.”

“Was?”

“Before my father passed.”

“What is your life now?”

The question pressed at her in a painful spot. She braced herself against the hurt. No matter what, she must not let Calhoun’s skepticism undermine her confidence. The horse had to learn to trust her, and if she wasn’t certain of her skills, he’d sense that. “You ask hard questions, Mr. Calhoun,” she said. Then she froze, and despite the rising heat of the day felt a chilly tingle of awareness.

“What is it?” he asked. “You’re going all weird on me again—”

“Hush.” She carefully laid aside her rake. From the corner of her eye, she spied the stallion on the beach path some distance away. “There you are, my love,” she whispered. “I knew you’d come.”

“What?” Calhoun scratched his head in confusion.

Eliza stifled a laugh at his ignorance, but she didn’t have time to explain things to him right now.

Hunter held out for as long as he could, but at last worry got the better of him. Taking the shovel in hand to use as a weapon, he followed Eliza’s footprints in the sand. No matter what she said, her scheme to pen the horse and train him was as insane as the woman herself. He had no idea why she thought she could tame a maddened, doomed horse that the best experts in the county couldn’t get near.

A sharp, burning tension stabbed between his shoulders as he quickened his pace. He kept imagining her broken, bleeding, maimed by the horse. Before he knew it, he was running, and he didn’t stop until he saw her.

As she had the day before, Eliza Flyte walked barefoot down the beach. And, just like yesterday, the stallion followed her. He was skittish at first, but after a while he started moving in close. She repeated the ritualistic moves—the turning, the shooing away, the staring down.

Hunter was intrigued, especially in light of what she had said about knowing what a horse was thinking by watching what he did with his body. Perhaps it was only his imagination, he thought, arguing with himself, but the horse followed her more quickly and readily than he had the day before. He stayed longer too, when she turned to touch him around the head and ears.

The docile creature, following the girl like a big trained dog, hardly resembled the murderous stallion. The horse that had exploded from the belly of the ship with fire in his eye. The horse they all said was ruined for good.

Hunter caught himself holding his breath, hoping foolishly that the girl just might be right, that Finn could be tamed, trained to race again. The notion shattered when the horse reared and ran off. This time the trigger was nothing more than the wind rippling across a tide pool, causing a brake of reeds to bend and whip. The stallion panicked as if a bomb had gone off under him. Eliza stood alone on the sand, staring off into the distance.

A parlor trick, Hunter reminded himself, trying not to feel too sorry for Eliza Flyte. Maybe she had put something in those apples she’d set out for the horse. Hunter wanted to believe, but he couldn’t. He’d seen too much violence in the animal. Letting her toy with him this way only postponed the inevitable.

“I can’t stay here any longer,” he informed her that evening. He stood on the porch; she was in the back, finishing with the cow. A cacophony of chirping frogs filled the gathering dark. “Did you hear what I said?” he asked, raising his voice.

“I heard you.”

“I have to go back to Albion,” he said. “I have responsibilities—”

“You do,” she agreed, coming around the side of the house with a bucket of milk. She walked so silently on bare feet, it amazed him. The women he knew made a great racket when they moved, what with their crinolines and hoop skirts brushing against everything in sight. And the women he knew talked. A lot. Most of the time Eliza Flyte was almost eerily quiet.

“Responsibilities at home,” he said. He had a strange urge to tell her more, to explain about his children, but he wouldn’t let himself. She disliked and distrusted him enough as it was. And he didn’t know what the hell to think of her.

“And to that horse you brought across a whole ocean,” she reminded him. “He didn’t ask for that, you know.”

“I never intended to stay this long. I swear,” he said in annoyance. “I can’t seem to get through to you, can I?” The craving for a drink of whiskey prickled him, making him pace in agitation and rake a splayed hand through his hair. “The damn horse is ruined. You’ve managed to get close to him a time or two, but that’s a far cry from turning him into something a person could actually ride.”

She set down the milk bucket. “We’ve barely begun. That horse is likely to be on the offense a good while. His wounds need to heal. He has to regain his strength and confidence. He has to learn to trust again, and that takes time.”

“Give it up, Eliza—”

“You brought him here because you thought there was something worth saving,” she said passionately.

“That was before I realized it’s hopeless.”

“I never said it wouldn’t be a struggle.”

“I don’t have time to stand by while you lose a struggle.”

“Fine.” She picked up the bucket and climbed the steps, pushing the kitchen door open with her hip. “Then watch me win.”

“Right.”

Yet he found himself constantly intrigued by everything about her. He felt torn, but only for a moment. Nancy and Willa looked after the children, and the Beaumonts’ schoolmaster at neighboring Bonterre saw to their lessons. Blue and Belinda wouldn’t miss their father if he stayed away for days or even weeks. The truth of the thought revived his thirst for whiskey. His own children hardly knew him. It scared them when he drank, and he often woke up vowing he wouldn’t touch another drop, but the thirst always got the better of him. Maybe it was best for them if he was gone for a while.

“I’ll strike a bargain with you,” he said to Eliza through the half-open door. “You get a halter on that horse without getting yourself killed, and I’ll stay for as long as it takes.”

The stallion greeted Eliza with savage fury. On the long stretch of beach that had become their battleground, he stood with his mouth open and his teeth bared. He flicked his ears and tail and tossed his head.

She fixed a stare on him and forbade herself to feel disheartened by the horse’s violence and distrust. Patience, she kept telling herself hour after hour. Patience.

The horse shrieked out a whinny and reared up. The sound of its shrill voice touched her spine with ice. She treated him with disdain, turning and walking away as if she did not care whether or not he followed. Perhaps it was the storm last night and the lingering thunder of a higher-than-usual surf, but the stallion behaved with fury today. He snorted, then plunged at her, and it took all her self-control to stand idly on the sand rather than run for cover.

She flicked the rope out. The horse flattened his ears to his head, distended his nostrils, rolled his eyes. Eliza stood firm. The stallion pawed the sand, kicking up a storm beneath his hooves. Yet even as he threatened her, even as the fear crowded in between them, she felt his indomitable spirit and knew one day she would reach him.

But not today, she thought exhaustedly after hours of trying to keep and hold his attention and trust. His whinny was more piercing than ever, and when thunder rolled and he shot away like a stone from a sling, she stood bereft, defeated, fighting the doubts that plagued her.

Taming the stallion became the most important thing in Eliza’s life. She tried not to examine her reasons for this, but they were pitifully clear, probably to Hunter Calhoun as well as in her own mind. It was not just Calhoun’s challenge, and her need to win the bargain they had struck, to make him stay and see this through. Nor was it any sort of softhearted nature on her part. No, her primary reason for dedicating herself to the violent, wounded horse was to bring herself closer to her father.

For some time now, she had been losing him by inches. Her father, whom she had adored with all that she was, kept slipping farther and farther away from her, and she didn’t know how to get him back. One day she would realize she had forgotten what his voice sounded like when he said “good morning” to her. Then she would realize she had forgotten what his hands looked like. And the expression on his face when he told her a story, and the song he used to sing when he chopped wood for the stove. Each time a precious memory eluded her, she felt his death all over again.

Yet when she worked with the horse, she felt Henry Flyte surround her, as if his hand guided her hand, his voice whispered in her ear and his spirit soared with her own.

So when the horse broke from her, pawed the ground with crazed savagery and ran until he foamed at the mouth, she wouldn’t let herself get discouraged. The stallion was a gift in disguise, brought by a stranger. The gift from her father was more subtle, but she felt it flow through her each time she locked stares with the horse.

Hunter wondered how much longer he should pretend he believed in her. He had stopped worrying that the stallion would murder her outright. So long as he wasn’t confined or restrained, Finn didn’t seem to go on the attack. As hard as Eliza worked with him, however, she seemed no closer to penning him than she had that first day.

Yet she went on tirelessly, certain he would become hers to command. Hunter decided to give her just a little more time, a day or two perhaps, then return to Albion. To pass the time, he did some work around the place, repairing the pen where she swore they would train the horse once she haltered him. The mindless labor of hammering away at a damaged rail was oddly soothing—until he accidentally hammered his thumb.

Words he didn’t even realize he knew poured from him in a stream of obscenity. He clapped his maimed hand between his thighs and felt the agony radiate to every nerve ending.

Eliza chose that precise moment to see what he was doing. Caliban—as ugly a dog as Hunter had ever seen—leaped and cavorted along the sandy path beside her.

“Hit yourself?” she asked simply.

Her attitude infuriated him. “I hammered my thumb. I think it’s broken. That should make you happy.”

“No, because if it’s broken or gets infected, you won’t be able to work. Come with me.”

He started to say that he didn’t plan to stay and work here any longer, but she had already turned from him. She led the way to the big cistern near the house and extracted a bucketful of fresh water. The big dog sat back on his haunches, the intensity of his attention seeming almost human.

“Ow,” Hunter said when she plunged his hand into the bucket. “Damn, that stings.”

“I know. It’ll be even worse with the lye soap.”

“Hey—damn it to hell, Eliza.”

Caliban growled a warning. Clearly he didn’t like Hunter’s threatening tone to his mistress.