Полная версия

The White Ship

THE WHITE SHIP

Conquest, Anarchy and the Wrecking of Henry I’s Dream

Charles Spencer

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2020

Copyright © Charles Spencer 2020

Cover design by Jo Thomson

Lions © Shutterstock

Canvas texture © Miroslav Boskov/Getty Images

Charles Spencer asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

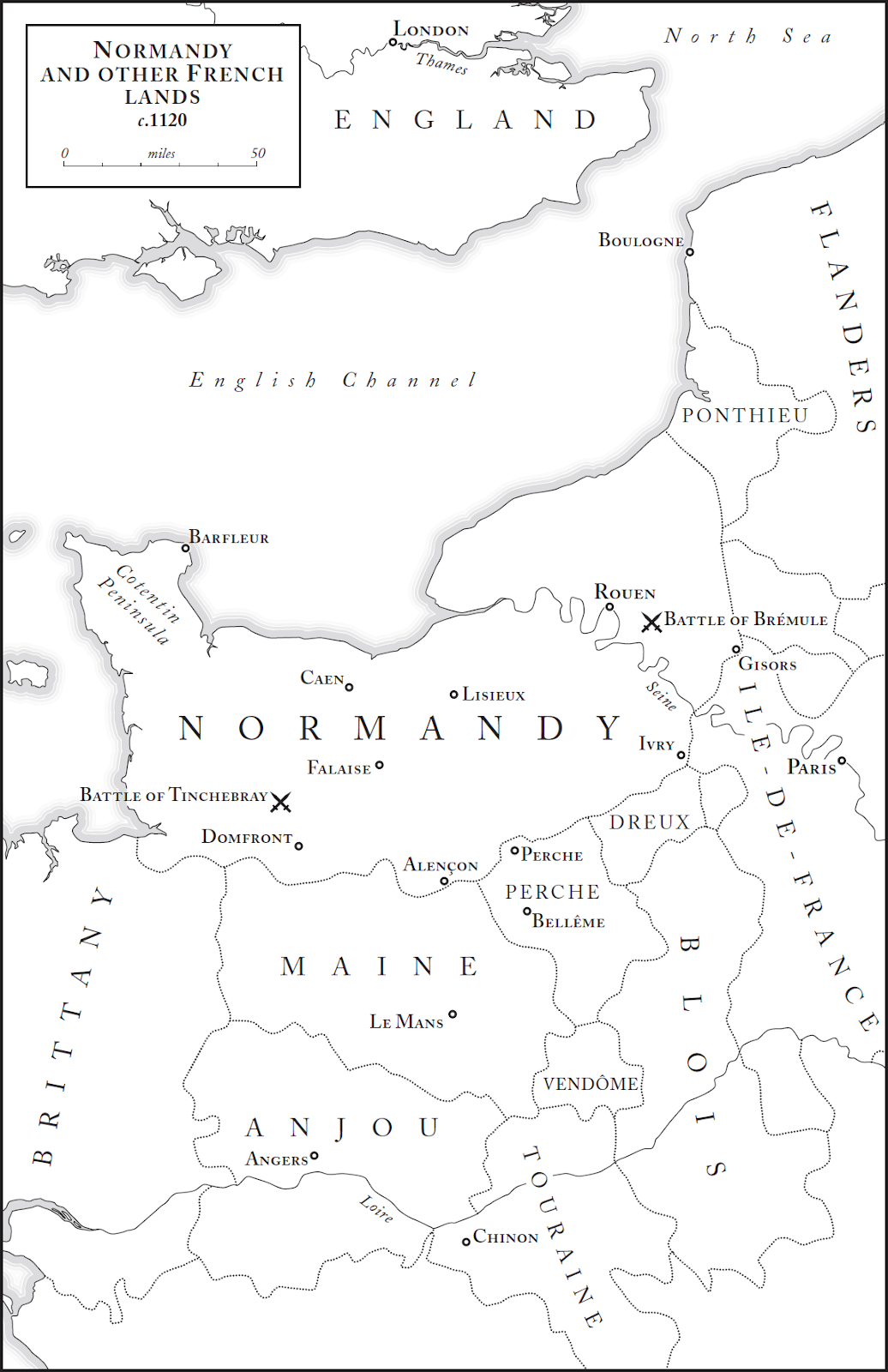

Maps by Martin Brown

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780008296803

Ebook Edition © September 2020 ISBN: 9780008296827

Version: 2020-08-25

Dedication

For Christopher Dixon, who taught me forty years ago, and who inspired me to write.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

List of Illustrations

Maps

Prologue: A Cry in the Dark

PART ONE: TRIUMPH

1 Conquest

2 Youngest Son

3 Out of the Shadows

4 Opportunity

5 Consolidation

6 The Heir

7 Kingship

8 Louis the Fat

PART TWO: DISASTER

9 Contemplating Rewards

10 The Sea

11 Bound for England

12 Reaction to Tragedy

13 The Empress

PART THREE: CHAOS

14 A Surfeit of Lampreys?

15 Stephen

16 Unravelling

17 Anarchy

18 Order

Picture Section

Footnotes

Notes

Bibliography

Index

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Also by Charles Spencer

About the Publisher

List of Illustrations

William the Conqueror (Getty Images / Fine Art)

William’s flagship portrayed in the Bayeux Tapestry (Getty Images / Heritage Images)

Sea monster marginalia, from St. Gallen, Stiftsbibliothek, Cod. Sang. 863, p. 47, Pharsalia Libri Decem ( https://www.e-codices.ch/en/list/one/csg/0863)

Manuscript image of Pope Urban II at the Council of Clermont (Getty Images / Ann Ronan Pictures)

Archbishop Anselm (Alamy / The Picture Art Collection)

The Death of King William II, from Royal 16, G. VI, f.272, Les Chroniques de Saint Denis (© British Library Board. All Rights Reserved / Bridgeman Images)

The Coronation of King Henry I, from MS 6712 (A.6.89) fol.115v, Flores Historiarum (Bridgeman Images)

Family tree showing King Henry I, Queen Matilda and William Ætheling, from Royal MS 14 B V, Genealogical Chronicle of the English Kings (© British Library Board. All Rights Reserved / Bridgeman Images)

The Battle of Tinchebray (Alamy / Art Collection 2)

Effigy of Robert Curthose at Gloucester Cathedral (Alamy / Angelo Hornak)

The hanging of thieves, from MS M.736, f.19v, Miscellany on the Life of Saint Edward (The Morgan Library and Museum)

The four kings, from Royal 14 C. VII, f.8v, Historia Anglorum (Alamy)

The Battle of Brémule, from BnF, MS. Fr.2813, f.201v, Grandes Chroniques de France (Bibliothèque Nationale de France)

William Clito

Louis VI of France (Alamy / Chronicle)

The White Ship sinking, from Cotton Claudius D. II, f.45v (© British Library Board. All Rights Reserved / Bridgeman Images)

The Blanche Nef (Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2020)

Henry I in mourning, illustration from Royal 20 A. II, f.6v, Chronicle of England (Bridgeman Images)

Adeliza of Louvain, illustration from Lansdowne 383 f.14, Shaftesbury Psalter (© British Library Board. All Rights Reserved / Bridgeman Images)

The wedding banquet of Henry V and Matilda, from MS 373, f.95v, Chronicle of Ekkehard of Aura (The Parker Library, Corpus Christi College, Cambridge)

Henry I during a stormy Channel crossing, from MS 157 p.383, Worcester Chronicle (Bridgeman Images)

Queen Matilda holding a charter, from Cotton Nero D. VII, Golden Book of St Albans (© British Library Board. All Rights Reserved / Bridgeman Images)

The remains of Reading Abbey (Charles Spencer)

King Stephen at the Battle of Lincoln, illustration from Arundel 48, f.168v (© British Library Board. All Rights Reserved / Bridgeman Images)

Hangings at Bedford Castle, from MS 16, f.64r, Chronica Majora (The Parker Library, Corpus Christi College, Cambridge)

King Henry II arguing with Thomas Becket, illustration from Royal 20 A. II, f.7v, Chronicle of England (© British Library Board. All Rights Reserved / Bridgeman Images)

Maps

PROLOGUE

A Cry in the Dark

Looking back on this, a night whose repercussions would change Europe’s history for ever, some claimed to remember nothing more than a distant noise. It had skimmed across the surface of the icy sea, the sound waves amplified by the stillness of the water, their notes hammered taut by the frost of a late November night.

It caught in the northerly wind, and perhaps reached the ears of those awake on King Henry I’s ship, a dozen nautical miles ahead in the voyage across the Channel. Those who claimed to have heard it in the dark would admit that they had no idea what it was. It was shrill and short-lived, like the distant squawk of a passing gull.

The same noise had made it back to shore – only a mile away – in a clearer form. Some in the Norman harbour of Barfleur heard it. They were near the point where they had earlier watched the port’s finest vessel, the White Ship, cast off into the night. Her departure had attracted a crowd – some present were related to those on board, and had come to say their farewells, while others were intrigued by the glamour and power of those putting out to sea.

These passengers included Henry I’s sole legitimate son, William, the seventeen-year-old heir to the kingdom of England and to the duchy of Normandy. Two of the king’s many illegitimate children, who were openly acknowledged and loved by him, were also aboard the White Ship. With the trio of royal children sailed much of the flower of the Anglo-Norman aristocracy, as well as leading bureaucrats who made Henry’s realm run smoothly and celebrated knights who kept the peace while protecting its borders.

The distinguished passengers had spent much of the afternoon and evening in the harbour, drinking hard and encouraging the crew to join in the revelry. Those in Barfleur who heard the noise assumed the merriment was reaching a crescendo on the White Ship, out at sea, and headed for the warmth of home, unsurprised and unconcerned by the cry in the dark.

In fact, what these witnesses to history had heard, at sea and on land, was a collective scream for help. The passengers of the White Ship had gone from wild festivity to dire panic in an instant, when they realised the crunch that had brought the vessel to a grinding halt was a rock – a rock that had pierced the timbers, leaving a gaping hole and allowing water to pour in. This caused the White Ship to heave to one side, making her spill her human cargo into the shockingly cold sea.

Perhaps the lowliest of those on board was Berold, a butcher from Rouen who had pursued his social superiors onto the ship, determined to get outstanding bills settled. Berold clung to part of the White Ship’s mast. Then, despite the weight of his saturated goatskin tunic, he hauled himself from the freezing waves onto this lifesaving perch. Next to him clambered Geoffrey de L’Aigle, a nobleman who was one of the king’s illustrious knights. The unlikely pair had rescued themselves from drowning, but now they lay vulnerable to the extreme cold. They shivered uncontrollably.

In the moonlight they watched as their companions cried out and thrashed in the water, desperate for life. Berold would later note William, the prince, getting safely away, in the White Ship’s small boat. The quick-thinking royal bodyguards had bundled him into it and were rowing hard for land, aware that their sole duty in this unfurling disaster was to preserve the life of the king-to-be. They had even left the royal treasure chest behind, in the White Ship’s hold.

As William headed quickly to safety, Berold and de L’Aigle watched with mounting horror as the tragedy around them played out.

PART ONE

ONE

Conquest

In the year of grace 1066, the Lord, the ruler, brought to fulfilment what He had long planned for the English people. He delivered them up to be destroyed by the violent and cunning Norman race.

Henry of Huntingdon, English historian and archdeacon (c.1088–c.1157)

The youth in the boat embodied the dynastic hopes of his royal father. King Henry I was in his fifties at the time that the White Ship was pinned on the rocks outside Barfleur. Unlike his son, who had been born as the undisputed heir to the throne, Henry had started life as a junior member of the royal family, seemingly destined for well-bred obscurity. But he had seized his chances to become one of the most powerful men in Europe.

Two decades earlier Henry had pounced on the English throne when it unexpectedly fell vacant. This he had done after leaving his elder brother on a forest floor to stiffen in death, rather than lose time tending to him. On that summer’s afternoon in 1100, Henry kicked his horse on into a gallop, his ruthlessness and speed enabling him to seize the royal treasury before any rival even knew the crown was in play.

Six years later he had stolen the dukedom of Normandy from his eldest brother. Henry crushed him in battle before casting him into prison, where he would remain, without hope of freedom, for the rest of his exceptionally long life.

Henry, English king and Norman duke, established strong rule over his lands by overcoming dangerously powerful enemies among the Anglo-Norman nobility. He was focused and uncompromising, clear in how he wanted to rule and determined that his way would prevail. Contemporaries noted that Henry had a face that looked friendly and open to humour, but people knew he could be harsh, and they heeded the steely intensity of his gaze. This was not a man to be trifled with, and his various rivals for power knew as much.

Apart from a hard-nosed drive, Henry also possessed subtlety. He was canny enough to deprive his enemies of diplomatic advantages. He ruled at a time when tensions over religious investiture were at their peak. Since the 1070s a succession of reforming popes had attacked the customary right of lay rulers to appoint bishops and abbots, key officers in the Church hierarchy. So closely fought was the contest that rival popes (‘anti-popes’) were set up and supported, while emperors and kings risked excommunication, or even being deposed.

In what became, for Christian leaders, one of the great questions of the age, Henry had insisted on maintaining his crown’s ancient rights, in the face of papal stubbornness that matched his own. But he was realistic and pragmatic enough to find compromise, long before the question would eventually be settled between pope and emperor. By doing so, he headed off the dangerous possibility of his many enemies harnessing papal power to their cause, which could in turn fatally undermine his position.

Contests for territory and power were a standard part of medieval statecraft. Many of Henry’s neighbouring rulers were also his relatives, through marriage or common ancestry: three of his wife’s brothers would, in turn, become kings of Scotland, and he maintained peace with each of them; while his bloodline sprang from the competing forces that lay off England’s southern flank.

Henry’s father, William the Conqueror, was the most celebrated Norman of them all. Henry’s mother, Matilda, was the daughter of the count of Flanders, a powerful figure from a land made wealthy by commerce: the fine reputation of its woollen cloth had been established in Roman times, and Flanders’s busy seaports traded with England and Scandinavia, before dispersing goods to France and Germany along inland arteries, principally the Rhine.

Henry’s mother was also, on her maternal side, a niece and a granddaughter of French kings. He was, therefore, a second cousin of the monarch who would prove to be his most persistent enemy, Louis VI of France: at the time of the wrecking of the White Ship Henry and Louis had spent much of the previous twelve years at war.

The France of the early twelfth century formed a different outline to the republic of today: it included what is now Belgium, while the Roman Empire controlled Burgundy in the south-east and Lorraine in the east.[fn1] The area that Louis truly dominated was more modest again, comprising as its core the Île-de-France. This royal heartland was surrounded by a constellation of other territories that enjoyed various levels of independence from its nominal overlord: the king of France claimed feudal superiority to his neighbours, but his scope for enforcing it was limited.

To the far west lay Brittany, a Celtic land that had seized its freedom in the ninth century and had remained self-governing ever since. To the east of Brittany sat the county of Maine, which had Anjou to its south. Maine and Anjou both extended eastwards to abut the county of Blois. Blois, in turn, bumped up against the western border of Louis VI’s axis of power. Meanwhile, when Louis looked to his north-west, he saw the imposing duchy of Normandy, whose capital, Rouen, covered a greater land area than his principal city of Paris.

Several generations of French kings had viewed Normandy as something of a pirate state. But in 1066 it transformed itself from the status of troublesome, subordinate neighbour to that of deadly rival. This was thanks to the gamble of one man, of Viking stock and persuasion, who had built a fleet to transport his army across the Channel and capture the kingdom he claimed by right.

In 799, speedy, shallow-draughted longships arrived on the French coast from Scandinavia, carrying marauders who had come to attack and plunder. These invaders were known as ‘Normanni’ – Northmen. The persistence and the savagery of their assaults succeeded eventually, in 911, in peeling off what became known as Normandy as a formal concession from Charles the Simple of France. In return for this tract of land that lay between the River Epte and the sea, the Norman leader, Rollo, swore three things: loyalty to the French king, protection against other raiders, and a willingness for he and his men to convert to Christianity.

He did well with the first two and gave his third commitment a good go. But on his deathbed Rollo’s true pagan leanings emerged for a farewell flurry. He had his Christian servants sacrificed to his ancestral deities: to Odin, the one-eyed god of wisdom, poetry and death, and to Thor, the fierce, hammer-wielding god of thunder.

This uncompromising warrior trait remained strong in the Norman genes. Henry of Huntingdon, a twelfth-century archdeacon who wrote the history of England from its earliest Anglo-Saxon roots up until his own time, recorded that the Normans ‘surpassed all other people in their unparalleled savagery’.[1] Abbot Suger, a French statesman and chronicler also writing in the twelfth century, said: ‘Being warlike descendants of the Danes, the Normans are ignorant of the ways of peace and serve it unwillingly.’[2]

Rollo’s successors certainly shared his instinct for warfare and ruthlessness. Rollo was followed by William Longsword, a son by one of his Christian lovers, who subscribed to his mother’s religion while aggressively adding new territory to his inheritance. Longsword’s marriage to the daughter of a powerful count cemented his place in the senior aristocracy of France. His bloody career was ended just before the Christmas of 942: while attending a peace conference on an island in the River Somme, he was ambushed and assassinated by order of the count of Flanders, a diehard enemy of the Norsemen.

Longsword’s son, Richard the Fearless, succeeded his father at the age of ten. The boy was taken into custody by Louis IV, the French king, as a first step towards retrieving Normandy for France. But the Normans were having none of it, capturing Louis and forcing him to give back their young duke. Richard would rule Normandy for more than half a century, during which time he opposed the Carolingian dynasty that was clinging to the French throne and helped his brother-in-law Hugh Capet to supplant it. He also reversed some of the devastation caused by his Viking forebears, restoring ravaged abbeys, resurrecting the archbishopric of Coutances and establishing a monastery at Mont Saint-Michel.

The house of Normandy’s influence extended further during Richard the Fearless’s lifetime. Two of his daughters became, respectively, duchess of Brittany and countess of Blois; while, in 1002, his eldest daughter, Emma, married Æthelred the Unready, King of England. For Æthelred, the match was a way of ending damaging Viking raids on his south coast, which emanated from Normandy.

Emma had three children with Æthelred, including the future king, Edward the Confessor. After Æthelred’s death she married Cnut, the man who eventually conquered her husband’s kingdom. She continued as queen of England, while also gaining the crowns of Denmark and Norway. The tide of Viking influence had now risen so high around Europe that its waves were washing back to Scandinavian shores.

Richard II succeeded to his father’s dukedom in 996 and held it for thirty years. Again, his prime duties were military: ruthlessly crushing a revolt by the Norman peasantry, seeing off an invasion from England and supporting his overlord – the French king – in campaigns against powerful Burgundy. Richard II’s rule saw Normandy become wealthy and stable, and he pushed ahead with reform of the Church. In return the grateful bishops and abbots gave strong support to the duke’s authority.

But Richard II left discord in his wake by splitting the Norman inheritance. While he consigned the bulk of his territory to his eldest son, another Richard, he left a county to his younger son, Robert. Dissatisfied with the size of his bequest, Robert rebelled and captured the castle of Falaise, the duke’s main power base in central Normandy, before being defeated. But Richard’s sudden and unexpected death soon after victory convinced many that he had been poisoned at his brother’s command.

Robert ‘the Magnificent’ – so-called because of his generosity – became duke of Normandy in 1027, aged twenty-seven. Soon afterwards he was said to have spied Herleva, an eye-catching resident of Falaise, as she bathed in a river. The daughter of a tanner, Herleva became the duke’s lover, bearing him two children out of wedlock. The elder of these, born perhaps in 1028, was called William.

In 1035 Robert announced that he was going on pilgrimage to Jerusalem, in penance for having seized Church properties when younger. Norman nobles insisted their ruler could not undertake such a dangerous expedition while without an heir. Robert countered by presenting them with the illegitimate William as his successor. He left his son in the guardianship of a handful of trusted aristocrats and courtiers, the most important of whom was Alan III, Duke of Brittany.

Robert reached Jerusalem successfully, but he died on the return journey. William, perhaps aged eight, was recognised as duke by many of his people and by his overlord, Henry I of France. Despite this, his life was in constant danger from those relatives of his late father who felt their claims, as members of the wider ducal family, born in wedlock, outshone that of the boy they called ‘William the Bastard’. One by one, his powerful guardians were murdered by cliques eager to control or replace the boy-ruler. William even awoke one morning to find his chamberlain in the bed next to him, his throat slashed open in silent assassination.

One of the young duke’s more powerful enemies was Guy of Burgundy, a cousin and former friend of William’s, whose rebel faction attempted to assassinate the teenaged duke during a hunting expedition in 1046. William escaped to safety alone, on horseback, before riding on to Henry of France, to demand the help the king owed him as Normandy’s feudal overlord.

The following year, the duke’s small force and the troops of the French king defeated the vastly superior numbers of Guy of Burgundy at Val-ès-Dunes, south-east of Caen. A freewheeling succession of cavalry skirmishes ended in utter defeat for the rebels, and many thousands of Guy’s men were cut down as they fled, while a great number of others were corralled into the Orne river. In an age when very few knew how to swim, they drowned. It took a further two years of siege warfare before William captured Guy of Burgundy and the castles that had underpinned his power.

In the struggle to impose his authority William acquired a ruthless streak. When the town of Alençon, on Normandy’s southern frontier, declared its support for the rival count of Anjou, William laid siege to it. Some of Alençon’s inhabitants, confident that their defences were impregnable, draped animal hides from the tops of the town walls in mocking reference to William’s mother’s humble roots as the daughter of a tanner. This was a mistake. When William eventually took Alençon, he ordered the hands and feet of those who had insulted Herleva to be cut off.