Полная версия

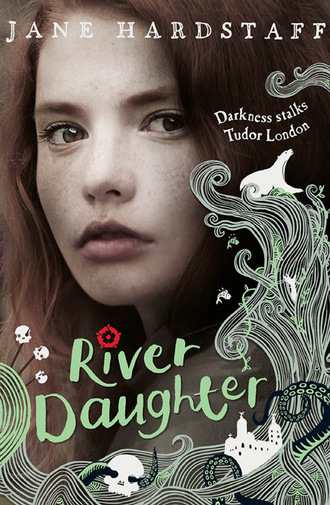

River Daughter

That evening they struck camp well before dusk, dragging the boat into a field. Moss gathered stout branches to prop underneath the upturned boat. It would be good shelter that night from the cold and rain. Grudgingly she accepted Salter’s offer to fish for their supper. It turned out he’d brought many things in his bag. His hooks and line, a hatchet, a pan to cook with and even some onions from her storebox. And before she knew it, they began to fall into familiar ways. Moss gathered wood and by the time Salter had a fish wriggling on the end of his line, the fire was lit and the pan was hot. That night they slept curled under the boat in their blankets.

When the birds woke them at daybreak, Moss insisted they pack up and move on straight away. They launched the boat back on to the river and Salter took the oars, while Moss settled back in her place at the front. Though she never took her eyes from the water, she saw nothing but riverweed and trout.

Before long the river grew wider. If there were coots or moorhens on this stretch, they didn’t show themselves. Once or twice Moss saw places where the grassy banks seemed to shrink from the water’s edge, pushed back by an oozing sludge. She caught glimpses of dead fish, slits of tarnished silver in the mud. And there was a smell. A rotten smell. Of dead things and fly-blown meat. A smell that had no place in a fresh, cold river.

They rowed all day, taking turns, sharing half a loaf of bread and some cheese, until their boat was gathered by the tug of the big river Thames as it swept past villages and towns towards London.

‘Can’t be more than twenty miles from the city now.’ Salter was rowing. It was almost sunset. ‘We’ll have to moor up somewhere soon.’

Moss dragged her gaze from the river and began looking up and down the banks for a good place to land. Through the branches of the tall oaks, she caught a flash of something bright. She stood up, craning her neck to get a better view.

‘Oi! Sit down!’

This broad sweep of river, it was familiar.

‘Just a minute. I think I know where we are.’

Lit by the October sun, a golden-turreted gatehouse rose above the trees.

‘Roll me in a barrel and drown me now!’ said Salter. ‘Ain’t that a sight.’

He steered the little boat round the wide river bend and there, spreading either side of the five-storey gatehouse, were the elegant brick walls of Hampton Court Palace.

‘Well, you can see why the King brings all his ladies down here. That is one fancy pile of bricks.’ Salter drew in the oars and let the boat glide with the current. ‘Ain’t this the place you told me you snuck into? Thieved a pigeon and a cloak if I remember right?’

‘I was desperate.’

‘Just like I always said. You learnt good that night, Little Miss Stealin-Ain’t-Right. Bread first, then morals.’

Moss rolled her eyes. It was true though. She’d never forget that feeling. So hungry, she’d have done almost anything to get her hands on some food. A different time. A frozen river. The palace covered in snow. She gazed at the high walls. How on earth had she managed it? She’d clambered through a kitchen window. There’d been hardly a guard in sight. Not like today. She stared at the line of armoured soldiers, pikestaffs pointing to the sky. The drover was right. King Henry was guarding his new queen as though she was made of glass.

As they drifted nearer, they could see there was quite a crowd gathered in front of the gatehouse. Moss could hear chatter and the cries of hawkers. The smell of spices and roast meat wafted on to the river.

‘Now that’s what I’m dreamin of, night in, night out.’ Salter licked his lips. ‘Warm gingerbread an’ mutton with the fat drippin down me chin.’

He dipped the oars back into the river, slowing the boat. ‘Why don’t we stop here? Just for a bit?’ He patted his pocket. ‘Got me three pennies. I’ll buy you a pie.’

‘Well,’ said Moss, ‘so long as we pay for it fair and square.’

‘What do you take me for?’ said Salter, grinning. ‘I’m an honest country boy now! All me rough edges hacked off good an’ proper.’

Somehow Moss doubted that was quite true, but she was hungry. And this was as good a place as any to try and find a field for the night.

Salter was hauling at the oars, but before he could turn the little boat towards the bank, a whip of current spun them around.

‘Whoah!’ he cried. ‘What was that?’

‘What?’

‘Get off !’

‘What’s the problem?’

Salter was tugging at his left oar.

‘Somethin . . . somethin’s got me paddle!’

Moss crawled to the middle of the boat and grabbed the oar. She could feel it. Something was pulling from below.

Splash! The oar flew from their grasp and landed in the water.

‘Quick!’ Salter leant over the side, trying to rake the floating oar back towards the boat.

All around them the grey water was turning green.

‘Salter –’

Thick coils of snaking waterweed were circling the boat.

‘Salter, forget the oar –’

‘Hell’s Chickens! Where did all this weed come from?’

‘Salter! Forget the oar! Hold on!’

‘What?’ For a split second, he looked up at Moss and saw her shocked face. Then they both grabbed the sides of the boat.

It all happened so fast. The boat flipped over, slamming the pair of them into the river. Moss felt her back ram against the upturned seat. Twisting round, she grabbed the boat and held on as best she could, but it surged forward with a force strong enough to carve its way through boulders. Her eyes were blind in the rush of water. All she could hear was the roar of the river. She spluttered and shouted, but could not move, pinned as she was, arms wrapped round the seat, clinging and gasping, feeling her grip slackening and knowing that if she let go, she’d be snatched by the current and tumbled in its fists like a rag in a boilpot.

All at once, she felt a great weight bearing down on the top of the upturned boat. The water choked her throat. She spluttered and retched, then something knocked the wind from her chest and the tumbling water faded away.

Boom! Boom! BOOM!

Such a pounding her ears had never felt. A storm ripping through her head. Thunder and lightning exploding all around her, loud enough to burst her eyes from their sockets.

In her mouth, the taste of mud. Her cheek against something wet and slippery, her eyes gummed shut and her body battered. She rubbed the mud from her eyes and lifted her head. She was lying on shingle, the river lapping her feet. The air was clogged with smoke. The boat was nowhere to be seen. Just a few feet away lay Salter. On his back, mouth open, eyes closed.

Moss crawled towards him, her knees scraping on the stones. She reached out and touched his hand. It was cold. She pressed her ear to his chest, but against the pounding explosions in the night sky, she could hear nothing.

‘Salter . . .’ She rolled his body on to its side. It convulsed and she watched as he erupted in a fit of coughing. Salter opened his eyes and they widened at the deafening noise all around them.

‘Devil eat me breeches,’ he croaked, ‘What the hell is goin on?’ He was looking about, but they couldn’t see a thing. He sniffed the air.

‘I’d know that smell anywhere,’ he said.

‘What smell?’ All Moss could smell was smoke.

‘Salt-mud. Smell of the old river.’

‘What? Are you crazy?’ But as she spoke, a sudden wind blew the smoke away and she staggered to her feet, almost toppling backwards into the mud.

Rising like a cliff in front of her were the sheer and mighty walls of the Tower of London.

She could not speak. Her head throbbed and she swayed, staring with disbelief from the Tower to the river to Salter and back to the Tower.

Now she could see that the deafening explosions were coming from inside the Tower itself. Cannons. Volley after volley. And all along the river, bonfires were burning. Had they woken up in some great battle? Washed up on the shore, only to be trampled by the stamping horses of an invading army?

Then the cannons stopped. The last wisps of smoke drifted away and in their place came the sound of cheering and laughter.

‘Somethin’s goin on,’ Salter pulled her arm. ‘Come on, let’s get near one of them fires, dry ourselves out.’

Moss hitched the skirts of her waterlogged dress and followed Salter up the bank to where an enormous bonfire blazed, flames snapping at the night sky.

A crowd was gathered around the fire. Two men in velvet caps filled mugs from a barrel as fat as a pony.

‘Bring your mugs and your jugs!’ cried one of the men. ‘Fill them up and drink them down and be as merry as you please, this night of nights!’

‘City merchants givin out free beer?’ said Salter. ‘Has the world gone mad?’ He marched up to the men.

‘Beer for you, lad?’ said the red-cheeked merchant.

‘What’s the night, mister?’

The merchant seemed taken aback by Salter’s question. ‘Where’ve you been this day, lad? Snoring under a hay bale?’

‘It’s a long story,’ said Salter.

The merchant laughed and raised his mug. ‘The Queen has had her child. The King has a son! Long live the Prince! We toast his health and thank heaven and all the angels, for England’s throne has an heir at last!’

There was a huge cheer from the men and women around the bonfire. Mugs clanked and the merchants’ boys threw on more logs. Now the smoke had cleared, Moss could see that London Bridge was a blaze of torches. Men dangled from the arches waving their arms. Long flags fluttered from the rooftops and the whooping carried down the river. It seemed to her as if all London had come out to shout and sing for the new prince.

‘Come on,’ said Salter. ‘We need to look for the boat and our stuff before the tide takes it back.’

Moss looked at the black river doubtfully. But she knew he was right. If there was a chance they could find it, they had to try. A broken boat and two wet blankets were better than nothing at all.

They scrambled back to the water’s edge and worked their way up the shoreline, prodding and scouring. But all they found were bits of old crate, bricks and bones, coughed up by the tide.

‘This is hopeless.’ Moss turned from the river and stared up the shore. Not far off, slumped like a tired army in the mud, were the fishermen’s tumbledown huts.

Salter was shaking his head. ‘Where is it?’ he muttered.

‘Let’s face it, the boat’s gone,’ said Moss. ‘We need to find somewhere to sleep. Salter ?’

‘Here,’ he said. ‘It was here.’ He was dashing to and fro like a mouse that had lost its hole. ‘It was here. I swear on me old nan’s teeth.’

Then he stopped. Sniffed the air. And looked down. Now he was on his knees, scrabbling in the shingle.

‘Salter, what are you doing?’

He pulled a piece of charred wood from the stones. ‘The smoker . . .’ He took a few steps forward and blinked with disbelief, turning in a slow circle and looking at the ground. He was standing on what could only be described as a pile of broken sticks.

And then she understood.

‘Oh, Salter, I’m sorry –’

‘Me old shack. It’s gone.’

Moss stared helplessly at where Salter’s hut had been. Never much to look at from the outside, inside the shack had been snug as two cats. Now it was smashed to tinder. A heap of wood, barely enough for an hour’s blaze.

‘Salter,’ she said gently, ‘it can’t be helped. All those children on the riverbank, hungry and frozen. When they realised you weren’t coming back, they’d have taken what they could. Come on. You’d have done the same.’

‘Maybe I would,’ said Salter gruffly. ‘But you ain’t never built somethin with yer bare hands, only to find it pulled to pieces like a chicken from its bones . . . Wait a minute.’ He patted his pockets. ‘Cussin collops!’ He kicked at the ground, sending a spray of shingle into the river. ‘All me coins must’ve fallen out.’

No money, no blankets and no boat. At least there were fires on the shore. There was a chance they wouldn’t freeze to death. They traipsed back to the bonfire and sat huddled together, backs to the heat, as close as they could get without setting themselves alight. And Moss must have forgotten the cold, because at some point she felt her head fall gently against Salter’s shoulder.

In the distance, cries and cheers mixed with the hush of the waves.

‘You asleep, Leatherboots?’ murmured Salter.

She was too tired to reply. But as sleep came, she felt the lightest touch of something soft on her forehead.

CHAPTER SIX

Cat’s Head

A howling river wind woke Moss early next morning. She lifted her head and sat up. Salter was still asleep, propped against an empty beer barrel. She guessed he’d dragged it over to the fire to shield them from the wind. She stood up and shook out her dress. It was smoky and specked with ash, but the wool was bone-dry next to her skin. Silently she thanked Pa. Without a blanket or a groat to her name, this dress was all she’d got.

‘Arrggh.’ Salter groaned himself awake. He stretched and his neck cricked. ‘Sweet Harry’s achin bones! Feels like someone chopped me head off and put it back the wrong way.’

Moss didn’t hear him. She was already down by the water’s edge, walking along the shore. The strangeness of their river journey was fresh in her mind – snatched by a freak current and dumped right in front of the Tower.

‘Hey! Leatherboots! Wait for me!’

Salter caught her up. ‘Where are you goin?’

‘Back to where we pitched up last night.’

‘Won’t do no good. Tide’ll have taken the boat. Won’t be nothin to find now.’

‘I know. I just –’ She broke off. What could she say? She wasn’t going to tell him about the Riverwitch.

But Salter was distracted by something else. The grey river raked the shingle, leaving a sticky sludge in its wake.

‘Steer clear of that mud, Leatherboots,’ said Salter. ‘You never know how deep this stuff is. Maybe it’s just an inch or two, or maybe it’s sinkin mud.’

‘Sinking mud?’

‘Deep as a pit, thick as porridge – mud that’ll trap you an’ pull at yer boots an’ the more you struggle, the more stuck you get. Till you ain’t got the strength to even call out fer help. And when it knows you ain’t goin nowhere, that mud will suck you down. Cold an’ thick an’ pressin the life from yer lungs. An’ there ain’t a thing you can do but watch yerself get swallowed slow.’

Moss stopped walking. ‘That’s what it felt like. That day the fish jumped out and I got stuck.’

Salter nodded. ‘It’s evil stuff an’ no mistake, an’ you don’t go near it if you can help it.’

They were almost at Tower Wharf. A putrid smell crept past Moss’s nostrils.

‘Holy dogbits!’ Salter’s nose caught the wind. ‘That’s disgustin! I think I’m gonna gip.’

The closer they got to the Tower, the stronger the smell, until Moss’s eyes were watering.

‘Hold it, Leatherboots. What is that ?’

Salter was pointing at a messy object, half buried in the mud not five feet from where they walked.

‘Wouldn’t touch it if I was –’

Too late. Moss was crouching by the muddy object, trying not to retch on the foulness that clawed its way down her throat.

It was a ball of matted fur, caked with river mud and what looked like old blood. Moss grabbed a stick and poked at it, rolling it over slowly. The matted fur was odd-looking. Speckled with a strange pattern, though it wasn’t easy to see through all the mud. The ball tipped on its side.

‘Oh!’

Moss jumped back.

Two startled eyes stared up at her – huge and black-ringed, faded by death. A lolling tongue poked through four enormous fangs. It was the head of some poor dead animal. Washed up by the tide.

Salter was beside her now. He whistled. ‘That is one big cat. What’s it been feedin on? All the other cats in town?’

‘That’s no cat,’ said Moss.

‘Got cat ears,’ said Salter. ‘Got cat eyes. And I reckon them straw things plastered to its fur are whiskers.’

‘Look at its teeth,’ said Moss. ‘When did you last see a cat with fangs the size of parsnips?’

‘Well, what is it then?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘Hey, what are you doin? Don’t touch that thing!’

Moss had lifted the head by the scruff of fur between its ears and was carrying it to the water’s edge. It was heavy. She swilled it in the grey water until the mud had rinsed off. Then she carried it back up the shingle and laid it down.

The creature’s head was covered in a strange pattern of round black patches, like a beautiful plague that spread from the line between its eyes across fawn-yellow fur.

‘It’s a good thing it’s dead,’ said Salter. ‘Those jaws would rip yer face off soon as look at you. Whatever that creature is, it ain’t from round here.’

At Salter’s words, something clicked inside Moss’s head and it filled with the memory of animal roars from long ago.

‘But it could be from round here.’

‘Eh?’

‘This creature. It could have come from the Tower.’

‘What? ’

‘From the Beast House.’

Salter nodded slowly. “I heard about that place. Wolves an’ snakes an’ weird birds, ain’t it?’

‘I only know what the Tower folk told me. That they are the King’s beasts. Rare and strange animals sent by the kings and queens of far away places.

‘You ever see em?’

‘No. I never went into the Beast House. Normal Tower folk weren’t allowed, only the keepers. On Execution days we’d walk right past and I’d hear the animals howling and roaring, but the keepers kept it locked.’

‘So,’ said Salter, ‘if you ain’t never seen em, what makes you think that mangy head is one of em? An’ even if it was, what’s it doin washed up on the shore?’

‘I don’t know.’

She stared up at the Tower. Its walls gave nothing away. Once these walls had encircled her whole world. Where she and Pa had lived almost her entire life. Stark and sheer, they blocked the sky. A howl echoed across the turrets, joined by another and another, as if the animals of the Beast House were crying out, trying to reach beyond the walls. Moss had never heard them howl like that in all the time she had lived in the Tower.

She looked down at the head of the beast. Its face was a frozen snarl. However this creature had died, she was pretty sure it hadn’t passed away peacefully in its sleep.

‘We’ll bury it,’ she said.

‘You what?’

‘It shouldn’t be here. We can’t leave it slopping in and out with the tide.’

Salter spent the next ten minutes grumbling while they scrabbled a hole in the shingle near the bank, deep enough to take the creature.

When the head was buried, Moss walked back to the mudline.

The rotten smell was still there. It was everywhere. In her hair, in her nose. She could taste it on her tongue. It was the smell of death and it hung around the Tower like a stinking fog.

‘Ready fer breakfast?’

‘Not really. Anyway, we’ve no food. Or money.’

There was a flicker in Salter’s eye. Tiny. But Moss caught it.

‘Salter, no.’

‘What?’ He laughed. ‘You don’t even know what I’m plannin!’

‘And I don’t want to know.’

‘Look, I ain’t lyin to you. It’s a scam all right. But it only takes from the pockets of them that can afford a groat or two. Nothin big. Nothin fancy. We won’t get caught. All you need to do is –’

‘No. Just . . . no. We’ve been in London one night and already you’re talking about thieving ?’

‘You got a better idea? Unless you want to turn round an’ walk back to the village right now?’

She didn’t.

Right now they needed food and a place to sleep. Surely there must be someone who’d give them shelter. Just for a night or two.

‘You lived on the river long enough,’ said Moss, ‘You must know somewhere we can go?’

‘Ain’t no one I can ask,’ said Salter. ‘It’s every man, woman and child fer themselves in this city. Ain’t no one who’ll take us in without a groat to show fer ourselves.’

‘Wait a minute,’ said Moss. In her memory, a thought stirred. A name from the past. She’d never met him, but Salter had talked about him. A boy. Someone Salter went to for . . . well, she wasn’t quite sure what he went to him for. But she remembered that he had helped Salter once, maybe twice.

‘Eel-Eye Jack!’ she cried. That was his name.

Salter’s brow creased.

‘Eel-Eye Jack,’ said Moss.

‘I heard you the first time. What about him?’

‘He’s your friend, isn’t he?’

‘Eel-Eye Jack ain’t no friend.’

‘You know what I mean. He helped you didn’t he? Helped you find me when I went to Hampton that winter.’

‘Eel-Eye Jack don’t help people.’

‘Oh, come on, Salter. We can ask him for a bed and a bit of food, just enough for a few days.’

‘No.’

‘What do you mean no?’

‘I mean no pussin way. I mean Eel-Eye Jack ain’t the kind to be askin favours from.’

‘Salter, don’t be ridiculous. We’ll find a way to pay him back.’

‘I’m serious. I ain’t never been in debt to Eel Eye Jack. Done all me business on an equal foot. An’ there’s good reason for that. When he calls in his favours, you don’t know what he’ll ask.’

‘What are you afraid of, Salter?’ Moss could feel the heat rising in her throat. ‘You don’t want to ask for help? Is that it? You take care of yourself, let others take care of themselves. You’d lie and steal rather than ask a friend for help.’

‘That’s not true.’

‘So prove it.’

Silence. She was up close to Salter. Close enough to see the trouble in the brown eyes that were gazing straight into hers.

She blinked. They both stepped back.

Salter kicked the shingle. ‘All right. Have it your way. Just remember, he ain’t my friend. An’ whatever you think, he won’t be no friend to you neither.’

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.