Полная версия

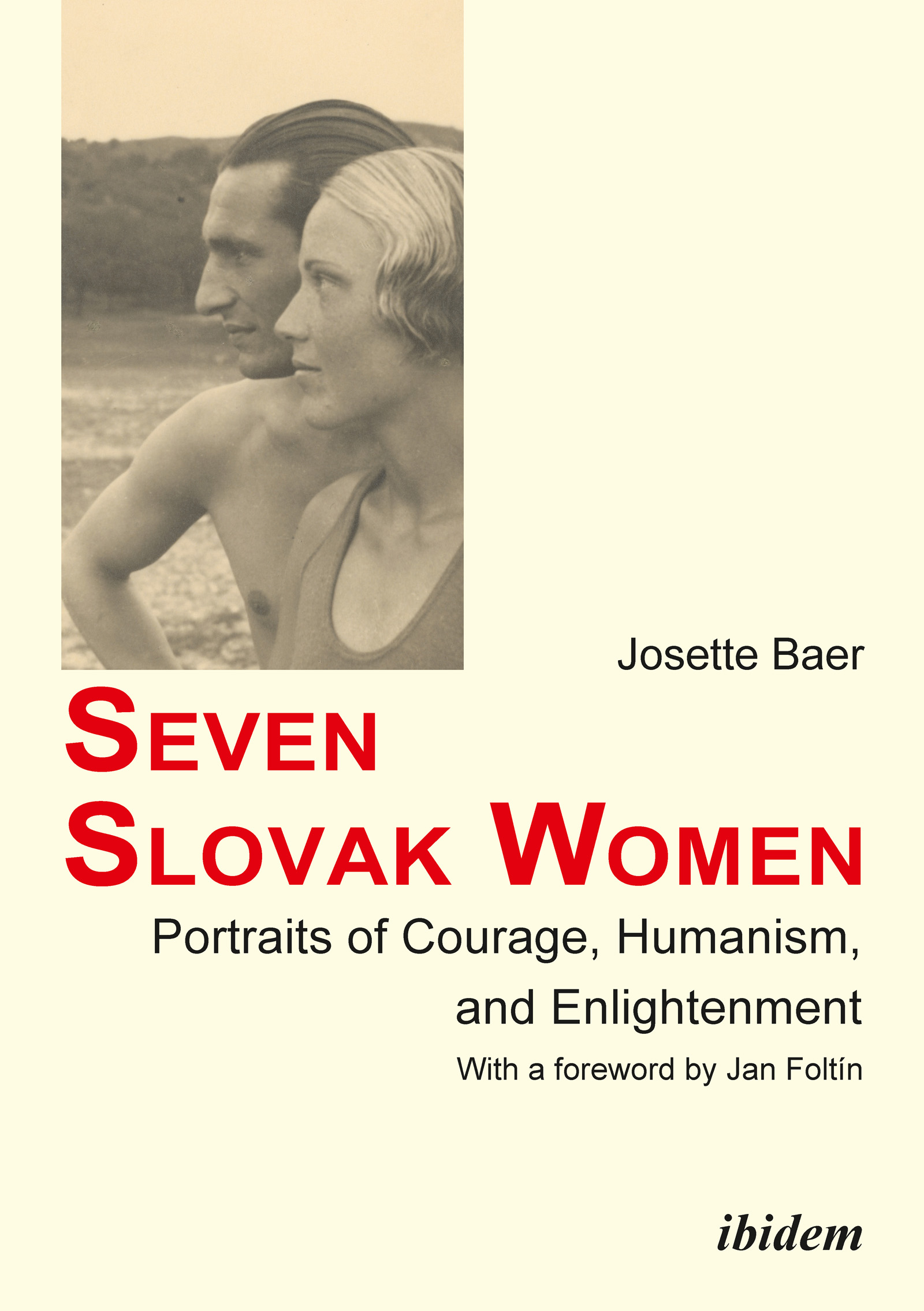

Seven Slovak Women.

ibidem Press, Stuttgart

This study is dedicated to Slovak women in particular and women in general, wherever they live.

Table of Contents

Foreword

Acknowledgements

X. Introduction

X. 1 Criteria of selection

X. 2 The portraits

X. 3 The method

X. 4 A brief word on gender studies in Central Europe

I. Elena Maróthy-Šoltésová (1855–1939) – the first feminist?

I. 1 The historical context

I. 2 The feminization of the nation

I. 3 Živena – the Slovak women's association

I. 4 Elena – chairwoman and writer

I. 5 The education of girls

I. 6Živena – conservative or feminist?

I. 7 New times and old issues

I. 8 Conclusion

II. Mária Bellová (1885–1973) – the first female physician

II. 1 The historical context

II. 2 "Medicine is not for you. Find yourself an occupation suitable for a woman!"

II. 3 Medicine, not politics – Mária's life-long dedication

II. 4 Conclusion

III.Chaviva Reiková (1914–1944) – a Jewish resistance fighter

III. 1 The historical context

III. 2 A Slovak Jew and a patriot

III. 3 Women in the Slovak National Uprising (SNP)

III. 4 Chaviva's last days

III. 5 Conclusion

IV. Anna Štvrtecká (1924–1995) – a courageous historian

IV. 1 The historical context

IV. 2 Anna Štvrtecká, a Party historian critical of the Party

IV. 3 Normalizácia – the politics of normalization in Slovakia

IV. 4 Anna's critique of the normalization

IV. 5 Conclusion

V. Magdaléna Vášáryová (*1948) – actress, diplomat and politician Oral history interview, Bratislava, 9 July 2014, 12.00-12.50, conducted in Slovak.

VI. Iveta Radičová (*1957) – the first female Prime Minister Oral history interview, Bratislava, 8 July 2014, 13.00 – 13.50, conducted in Slovak.

VII. Adela Banášová (*1980) – the face of young Slovakia

Conclusion

Appendix

Chronology

Bibliography

Abbreviations

CC Central Committee of the Communist Party DS Demokratická Strana – Democratic Party HG Hlinkova Garda – Hlinka Guards HSĽS Hlinkova Slovenská Ľudová Strana – Hlinka's Slovak People's Party HZDS Hnutie Za Demokratické Slovensko – Movement For a Democratic Slovakia KSČ Kommunistická Strana Československá – Czechoslovak Communist Party KSS Kommunistická Strana Slovenska – Slovak Communist Party ODS Občanská Demokratická Strana – Civic Democratic Party OF Občanské Forum – Civic Forum OSS Office of Strategic Services RAF Royal Air Force SAV Slovenská Akademie Vied – Slovak Academy of Sciences SDKÚ-DS Slovenská Demokratická Kresťanská Únia-Demokratická Strana – Slovak Democratic Christian Union-Democratic Party SNK Slovenská Národná Knižnica, Martin – The Slovak National Library, Martin, Slovak Republic SNR Slovenská Národná Ráda – Slovak National Council SNP Slovenské Národné Povstanie –Slovak National Uprising SNS Slovenská Národná Strana – Slovak National Party SOE Special Operations Executive SSl Strana Slobody – Party of Freedom ŠtB Štátní Bezpečnosť – State Security Service WAAF Women's Auxiliary Air Force VPN Verejnosť Proti Násilie – Society Against ViolenceForeword

Dear Readers

The book you have before you is Professor Josette Baer's study of seven Slovak women, significant figures in the history and contemporary life of the country.

I was aware of Mrs Baer's work from the Slovak media before my arrival in Switzerland in 2010. On the Internet I had found her interview with the popular station FUN Radio. As ambassador I was naturally interested since it is quite rare to find a native Swiss who focuses on Slovakia. That is why I met up with her and followed her work. I reacted spontaneously when she asked me to write the foreword to her latest study.

In four years as Slovak ambassador to Switzerland, I often had to deal with a lack of both knowledge and interest on the part of ordinary citizens concerning the Central European region, not only Slovakia. In this regard, Switzerland is different from Austria or Germany, for example, which have historical links and current interests in our region. In the past, Switzerland was concerned primarily with her larger neighbours Germany, France and also Italy. But what was happening behind the Iron Curtain was of little interest to the common citizen. It is a pity that, as a consequence of these circumstances, we see hundreds or thousands of Austrian and German investors in Slovakia, while Swiss investors can be counted on the fingers of two hands. That's why I greatly appreciate Mrs Baer's latest book. In her description of the lives of seven Slovak women, she not only presents their often complicated and tragic fates, but also the difficult journey of the Slovak nation from the mid 19th century to the present day.

Professor Baer chose four historical and three contemporary personalities who have exerted a significant influence on Slovak public life. Naturally, one can discuss whether other important personages should have been chosen. For example, the following distinguished women would not be out of place among the group of contemporary Slovak personalities: the economist and former Minister of Finance Brigita Schmönerová, the Deputy Governor of the National Bank Elena Kohútiková, who rendered great service with the smooth introduction of the euro, or the successful entrepreneur Mária Reháková. Also, the famous opera singer Edita Gruberová, already a legend, or the Olympic champion Anastázia Kuzminová, who won the gold medal for biathlon in successive Olympics.

However, the author's main aim was to describe the situation of Slovak women in different historical eras; from her viewpoint it was thus not a priority to choose specific life stories. For example, in her chapter about Elena Maróthy-Šoltésová she precisely describes the struggle of the Slovak nation for self-determination, particularly in the critical years following the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867. In those years, the Slovaks were threatened with oblivion: the fate of many European nations we know today only from historical studies. But the Slovaks survived, also – or perhaps mainly – thanks to their women, and today Slovakia is an equal member of the family of European and world nations.

The author's thoughts about the emancipation of Slovak women in specific epochs guide the reader through the book. As a man, I am probably not the most suitable person to make a judgement about this issue. I allow myself only to state that, with regard to female emancipation, Slovak women were not and are not worse or better off than Swiss women, or women in other countries of Central and Western Europe. One can muse on the significance for women's rights of Empress Maria Theresa, who ruled Austria-Hungary for forty years in the 18th century, or the decree on equality for men and women in Socialist Czechoslovakia. It is a fact – also mentioned by the author – that many female emigrants from the former Czechoslovakia were astonished to learn, when they arrived in Switzerland in 1968, that women didn't have the vote.

I would like to take issue in particular with the author's opinion that the dissolution of Czechoslovakia was unconstitutional. I remind readers that both chambers of the Federal Parliament voted in favour of the separation. From the viewpoint of the Swiss political system, I can see that it is difficult to understand why Slovak and Czech voters did not get a chance to decide about such an important issue. However, the reality that Slovaks and Czechs understand each other better today than in the times of the common state vindicates the former leaders who decided not to organize a plebiscite. An election campaign on the issue of separation could have provoked nationalist agitation and done severe damage to the relations of the two brotherly nations for many years to come.

I fully understand the author's aim to describe the Slovak National Uprising as a decisive episode of Slovak history, introducing the life and fate of Chaviva Reiková. In Slovakia, however, she is practically unknown, and the question arises, since the author also mentioned others active in the SNP in those years, whether a different woman representing that generation would not have been a better choice.

One task of a diplomat and, in particular, an ambassador is to present his country in a positive light. From this viewpoint, I was somewhat taken aback by what I consider an overly pessimistic view of Slovakia's post-89 development, as discussed in the interviews with Magda Vášáryová and Iveta Radičová. They certainly have a right to their own opinion and the legitimate critique of specific aspects of our development. However, after twenty years of independence, and in comparison with other countries of our region, Slovakia's development should undoubtedly be referred to as a 'success story', all the more so as the young state's starting point after the dissolution of Czechoslovakia was significantly less propitious than that of the neighbouring countries.

With my critical views I certainly don't want to diminish the significance of the author's work or cast doubts on her objectivity or knowledge of Slovak history. On the contrary, I believe that this study will help to fill specific gaps of knowledge about the young country that still prevail in Switzerland and, in view of the fact that the author wrote her study in English, also in other European countries. It is of no importance whether the majority of readers are women or men. I think that some of the information the author gathered in foreign archives and publications could also awaken the interest of specialist circles in Slovakia.

Jan Foltín, Ambassador of the Slovak Republic

to Switzerland from 2010 to 2014,

Bratislava, Slovakia, August 2014

Acknowledgements

At first glance, every historical study by a single author might seem to be just that. Yet, the author is never working alone, since every scholar who takes their profession seriously is in steady contact with their peers, with experts who can teach them about the particularities of a region's history and the subject under investigation. As a careful student of the difficult Czech, Slovak and common Czechoslovak histories I am honoured that my colleagues and friends in Slovak and Czech academe support me in my endeavours to present my views of their political history to the English-reading public.

The idea for this study was born in Bratislava and Martin. In the summer of 2012, my friend and colleague Gabriela Dudeková, a historian at the Slovak Academy of Sciences, gave me a copy of her book about family relations in Central Europe. Gabriela's book opened up a new world to me, the history of women and family relations in Central Europe through three centuries. Her analysis and that of her fellow authors answered many questions and addressed many issues I had been wondering about – suddenly things fell into place. Their scientific contributions raised the interest of the international community of historians: the Journal of Interdisciplinary History at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Press in Boston, USA, published my review of Gabriela and her co-authors' volume.

That same summer, I visited the Slovak National Library SNK in Martin for my annual research in the archives. I was looking for source material about Živena, the Slovak women's association in the 19th century. My friend, the librarian Ľudmila Šimková, who is knowledgeable about Slovak history and historiography to the point that I would like to call her the Slovak lexicon, a praise I am quite certain she would modestly and firmly reject, told me that it would be a good idea to write a book in English about Slovak women, since no such study yet exists. Ľudmila, here it is.

My thanks. I am greatly indebted to my colleagues and friends for their interest in my research and willingness to discuss specific issues with me. My thanks, in alphabetical order, go to Valerián Bystrický, Gabriela Dudeková, Karen Henderson, Karol Hollý, Adam Hudek, Vlasta Jakšicsová, Ivan Kamenec, Daniela Kodajová, Dušan Kováč, Slavomír Michálek, Jan Pešek, Jaroslava Roguľová, Stanislav Sykora, and Jozef Žatkuliak. Thomas Hardmeier is always available when I have a question about medicine; he is a retired professor of pathology and a meticulous researcher and scientist. Dan Holcer, born in Komárno and now living in Israel, helped with the translations from Hebrew and the details of Israeli history. Jan Foltín, the former ambassador of the Slovak Republic to Switzerland, supported this project from the start and I am honoured that he agreed to write the foreword.

My special thanks go to the ladies at the Slovak National Library SNK in Martin for their tireless and outstanding services. Diana Manevich from the Yad Vashem library in Jerusalem sent me archive material in a swift and uncomplicated manner. Mária Bohumelová and Anton Kajan of the Slovak National Gallery SNG in Bratislava provided me with the cover picture of Juraj Jurkovič, which I had first seen in the exhibition Nové Slovensko/New Slovakia in 2012. The ladies at the housing office of the Slovak Academy of Sciences SAV have made my annual research stays since 2008 such a joyful and uncomplicated matter: Mária and Lenka Vallová, Božena and Ľubica Konečná, thank you. Valerie Lange at ibidem publishers in Stuttgart is an exceptionally patient, effective and supportive editor. Peter Thomas Hill proofread the manuscript, patiently soldiering on with the demanding task of teaching me English that is up to his own high standards.

I would like to express my gratitude and respect to the ladies who agreed to participate in my oral history interviews: Magdaléna Vášáryová, Iveta Radičová and Adela Banášová, your ésprit, commitment, modesty, beauty, honesty and intellect are inspiring – you are in a league of your own.

The errors and shortcomings in this volume are my own.

Josette Baer

Zurich, Switzerland, and Bratislava, Slovakia, September 2014

X. Introduction

This book[1] has been on my mind for two years. I was inspired to write about the political and social endeavours of Slovak women by a study that my friend Gabriela Dudeková published in 2011.[2]

As a political scientist focussing on the history of political thought in Central Europe and a careful student of Czech, Czechoslovak and Slovak history, I admired Gabriela's study; in an impressive tour de force reaching from the 19th to the 21st centuries, she and her fellow authors analysed the situation of women in the Czech lands, Slovakia in the Hungarian Kingdom, Hungary, Austria and Czechoslovakia, providing copious historical analysis based on archive material in four languages. Most valid is the fine fabric of social history: I had a precise and vivid picture of what it meant being a woman in those days, the range of freedoms and limitations Central European women faced under the various political regimes.

My study cannot compare with Gabriela's seminal volume, which is both the reference book par excellence on family relations in the Central European region and an important contribution to gender studies.[3] My intention is rather modest: I would like to present to the Western reader the history of Slovakia seen through the eyes of seven women who rendered outstanding service to their nation. All seven have three things in common: they have a Slovak cultural and political identity, they were or are in the public eye and they have engaged in education, science, the arts, politics, the humanities and the media, that is, in crucial areas of Slovak society.

The portraits range from the late 19th century to contemporary Slovakia, presenting the activities of these women on behalf of their co-citizens. In their endeavours, all of them attempted or are attempting to make life better – for all Slovak citizens, not just women. In a wider framework, they represent the ethical values of modern Europe – 'Europeanness'. They are committed to values that the young generation of today considers normal, standard, guaranteed. Yet, in their times, these values were far from being standard, let alone constitutionally granted. They were but ideas that had to be fought for, ideas of a better and more just world that had to be put into practice. The women portrayed here campaigned for these values, and those alive today are still fighting for them on a daily basis.

X. 1 Criteria of selection

I selected the seven women on subjective grounds since they represent the spirit and reality of seven distinct historical eras of Slovak and Czechoslovak history. My three criteria for selection are: first, the seven women's visibility in the Slovak, Czechoslovak and European public eye; second, their activities not only for their nation, but also for the promotion of universal ethical values; and third, their physical presence in Slovakia, the fact that they stayed in their country and did not – for example – emigrate in 1945, 1948 or 1968.[4] After WWII, former officers and soldiers went to great lengths to flee with their families: most of them had fought in the Czechoslovak exile army shoulder to shoulder with the British, returned home in 1945 and then decided to flee as soon as the Communists took over in February 1948, in some cases using skills acquired in the war to take spectacular leave by stealing a Dakota and in another even driving a train across the border.[5]

In the years of the Cold War, the irrational refusal of some Western intellectuals to believe what witnesses and refugees reported about the Communist regimes in Eastern Europe can be explained by what the French liberal thinker Raymond Aron (1905–1983) called The Opium of the Intellectuals,[6] an almost esoteric adherence to Marxism-Leninism. Tony Judt (1948–2010), a renowned expert on French political thought, described the atmosphere among French leftist intellectuals in the 1960s:

"There was thus an aura of romance surrounding the Communist adventure that gave to its failings and mistakes a truly heroic quality. This can be sensed even in the memoirs of the victims themselves, who shared with their French sympathizers and apologists a common feeling of tragic destiny."[7]

Artur London (1915–1986), born in Moravia into a Communist family, had fought in the Spanish Civil War, survived the Nazi concentration camp of Mauthausen, the Stalinist show trials of the 1950s and was rehabilitated in 1963. He could never fully distance himself from Marxism-Leninism and the Party.[8] He emigrated to Paris and joined the leftist French radicals, who were supportive of his conviction that his terrible experience had a deeper "metahistorical level of meaning".[9] Marxism-Leninism and the Party never ceased to be his intellectual home. London, a witness to the trial of the former general secretary of the Czechoslovak Communist Party KSČ Rudolf Slánský (1901–1952), about his loyalty:

"I never lost faith in the strength and purity of the communist ideal … "[10]

By contrast, the wives of convicted Party members had quite different views about the regime. Heda Margolius Kovály (1919–2010)[11] and Josefa Slánská's (1913–1995)[12] memoirs provide lively descriptions of the frightening atmosphere in Prague in the 1950s. Jo Langer's (1912–1990) memoirs of Simone Signoret (1921–1985), the famous French actress and her distant cousin, illustrate the ignorance of Western intellectuals about life under Communism.

In 1934, Jo, born Žofia Bein, a Hungarian Jew from Budapest, had married the economist Oscar Langer, a Slovak Jew and Communist; they lived in Bratislava and she had Czechoslovak citizenship. They emigrated to the USA in 1938 and returned to Bratislava after WWII. Oscar had a high position in the Central Committee, and they enjoyed the economic privileges of the nomenklatura.

With Oscar's arrest in 1951, Jo and her two young daughters were catapulted into economic hardship and social apartheid. In 1953, the authorities sent her to the countryside in the so-called Akcia B (Action B), a kind of Communist 'kin liability', extended to the families of Party members accused in the show trials. One rationale of Akcia B was to isolate the wives and children of the convicted Party members; they were politically unreliable, infested with the virus of treason. In the countryside, they would learn how to work with the peasants and workers. The second and more important reason for Akcia B was the transformation of the capital's social structure: the Party's intention was to give the apartments of doctors, lawyers, university professors and entrepreneurs, that is, the urban intellectual elite, to workers; yet, mostly Party members, policemen and personnel of the ŠtB, the domestic State Security Service, moved into the approximately 1500 apartments and houses of 672 evicted and deported families.[13]

In 1955, Jo returned illegally to Bratislava and supported her daughters by doing translations. In the more liberal atmosphere of 1967, the months preceding the Prague Spring, she managed to arrange a meeting with Simone Signoret in London. Simone's appeal to the Czechoslovak authorities would certainly help to free Oscar, or so Jo must have thought. Her intention was to ask Simone for support, explaining to her famous cousin that her husband had been arrested in 1951 and accused of conspiracy against the state. The false testimony the authorities had made him give by way of torture and appeals to party discipline was used to legitimate the trial and execution of Rudolf Slánský and former Foreign Minister Vladimír Clementis (1902–1952) in 1952. Oscar's role was that of a witness to Slánský and Clementis' 'crimes'. Jo on the meeting with Simone:

"I was anxious to explain, why I had appeared so eager ten years earlier, and I was also longing to take this unique opportunity of talking with a representative of that (to me) incomprehensible species, the French intellectual left, and seeing for myself if they really did not know, or just preferred to ignore, the truth about the régimes still so staunchly supported by l'Humanité. … I had hardly started when she cut me short by saying 'But if you had stayed in New York your husband, as a communist, would have met with very much the same fate.' I fell silent. When she asked me to go on with my story I said it was useless. I excused myself … and left."[14]