Полная версия

The Ship of Dreams

For decades, this shift has popularly been attributed to White Star’s desire to distance the third sister from the tragedy of the second by abandoning a too similar name. This is a logical explanation for how the Gigantic became the Britannic, especially in light of White Star officially filing for the new name a few weeks after the Titanic sank, but it is also incorrect. The alternative name of Gigantic seems to have been genuinely considered by the White Star Line only at the earliest stages in the vessel’s development and some of their contractors continued to use it, even after it had been abandoned – the order books for the English firm that made the liner’s anchors referenced her as Gigantic as late as 20 February 1912 – as did several Harland and Wolff employees, who remembered the original name in interviews given in the 1950s. Rumours that the ship was to be christened Gigantic were current and firmly denied by the White Star’s Managing Director, both in his testimony to the American inquiry into the loss of the Titanic and subsequently in a letter to a British newspaper.[37] Those printed denials may have been the company’s response to letters they had received from concerned members of the public, begging them not to tempt fate by giving the new ship a name so similar to the Titanic’s, although at least one of the latter’s survivors was sufficiently hardy to dismiss that as superstitious nonsense, ‘almost as if we were back in the Middle Ages’.[38] More prosaically, it was almost certainly the Imperator that prompted the rechristening. Since, by 1915, the Britannic would ‘only’ be the third largest ship afloat, behind the Imperator and her 1914-projected running mate, the Vaterland, to call her Gigantic under those circumstances seemed foolhardy.[39]

The Titanic’s looming black-painted hull, summoned into being by capitalist competition and the diplomatic thrombosis of pre-war Europe, greeted the Thayers as the Nomadic at last docked alongside the Titanic. The tender’s gangplank could not safely reach the B-Deck embarkation doors used at Southampton and so Tommy Andrews had designed another, two decks lower, reaching a vestibule which opened on to the first-class Reception Room, where stewards waited to guide first-class passengers to their cabins and second-class aft to their section of the ship. Standing in front of the Thayers as they boarded was J. Bruce Ismay, son of the White Star Line’s late founder and Managing Director since its merger with the IMM. If the Titanic’s legend has a two-dimensional caricature, it is Ismay, cast as both vulpine villain and a serial weakling in the hysterical aftermath of the sinking. So complete was Ismay’s historiographical evisceration that when a consultant first saw the script for what became a multi-Oscar-winning cinematic romance set on the Titanic and queried the characterisation of Ismay as a megalomaniacal moron, butt of penis-envy jokes he cannot understand and shameless manipulator of the Captain in the dangerous quest for more speed, he was told there was no point in changing it because ‘the public expects’ a heinous Ismay.[40] That is not to say that Ismay was incapable of moments of mind-boggling stupidity, but he was also astute, devoted to his company and, like Tommy Andrews, obsessed with detail.[41] A complex man whose inherent shyness produced acts of great kindness and flinch-inducing obtuseness, Ismay’s thoughtfulness had won out on 10 April as he bore down on the Thayers’ travelling companions and lifelong friends, Arthur and Emily Ryerson, who were returning home to America unexpectedly after hearing that their son, Arthur Junior, had been killed in a car accident during his sophomore spring at Yale. He had gone home to Bryn Mawr in Pennsylvania for the Easter weekend where he had died, along with his classmate, John Hoffman, two days before the Titanic sailed.[42] Ismay took over from the Thayers as temporary chaperon of the grief-stricken by informing the Ryersons, who were travelling with their three younger children, a maid and a governess, that he had arranged for them to be given an extra stateroom adjoining those they had already booked, along with a personal steward to look after them during the voyage.[43] A broken Emily Ryerson intended to spend the trip in her cabin with her family, avoiding everyone else on board except the Thayers.

Less solemnly, a middle-aged New York widow, Ella White, was carried past the boarding passengers. She had fallen and sprained her ankle as the gangplank swayed in the winds.[44] A few stewards had been summoned to help Mrs White’s chauffeur lift her to her C-Deck stateroom, the same deck where the Thayers were also settling into their accommodation on the opposite corridor to the Strauses and the Countess of Rothes. The latter escorted her parents down to the Reception Room to see them off on to the Nomadic. Noëlle, Thomas and Clementina descended the staircase into the Reception Room. Directly ahead of that, they turned left at a wall mounted with a reproduction of the Chasse de Guise tapestry, depicting a hunting party, the original of which had been owned by the French aristocratic family unfairly accused of poisoning the 4th Earl of Rothes in the sixteenth century.[45] From two sets of double doors leading off the Reception Room into the Dining Saloon, the Countess and her parents heard hundreds of passengers tucking into their second meal of the voyage. They walked over dark Axminster carpets, past settees, armchairs, white cane chairs with green side pillows, potted palms and a Steinway piano, one of six on board, into the small vestibule that opened on to the gangplank and the night air.[46] Thomas and Clementina said their farewells, but at the last minute the normally reserved Clementina turned on impulse and dashed back to give her daughter a final embrace.[47] When the Dyer-Edwardeses joined the Titanic’s thirteen other cross-Channel ticket holders in the tender, the gangplank was disengaged and the boarding doors were closed. After they had been locked, crew members pulled wrought-iron gates back into place to shield the utilitarian steel from the passengers’ view.

The usual expectations governing dinner, including the formal dress code, were typically eschewed on the first night out.[48] Wearing the dress in which she had boarded, Noëlle left the vestibule for the Saloon, which has since become one of the Titanic’s most recognisable rooms thanks to its frequent depiction in silver-screen dramatisations of the voyage.[49] Meals in the Saloon were run on the same lines as they might be in a country house on shore, with limited options, generous portions, set times for each course every evening except the first, and placement decided by the host – in this case, the ship’s Purser, who assigned passengers to one of the 115 tables which variably sat two, three, four, five, six, eight, ten or twelve. His decisions with this social roulette could introduce a passenger to delightful week-long shipboard acquaintances or purgatorial companionship in a multi-course dinner that moved with the sprightliness of a state funeral. You could, of course, ask the Purser’s Office to move you to another table if you found the company particularly stultifying but, as a passenger on the Queen Mary noted later, ‘the cost of [which] would be the contempt of those still seated at the table you had spurned, and the frozen stares with which they’d greet you on deck for the rest of the trip’.[50]

Where to put a countess and her companion would have been one of Purser McElroy’s main priorities and it seems, from a letter sent by one of their stewards, that they won the lottery in their three gastronomic companions. A steward was assigned to every three diners and it was considered proper for those in his care to leave a gratuity at the end of the voyage, the amount of which very often outpaced his wages. The Countess’s Steward, Ewart Burr, described her group as being ‘very nice to run’. He was particularly pleased to have an aristocrat at his table and he made a point of mentioning it in the note he penned to his wife that evening, writing, ‘I know, darling, you will be glad to know this. I have got a five table, one being the Countess of Rothes, [who is] nice and young.’ Burr predicted that they would be generous at journey’s end or, as he put it, ‘I shall have a good show.’[51]

The decor in the Dining Saloon was loosely inspired by Elizabeth I’s childhood home at Hatfield Palace and the dukes of Rutland’s house at Haddon Hall. Despite both those buildings being Elizabethan and the Tudor roses in scrollwork on the Saloon’s roof, trade journals described the Titanic’s Saloon as reflective of ‘early Jacobean times’.[52] The green-leather chairs with their oak frames were heavy enough for White Star to do away with the bolted-to-the-floor chairs used on the Kaiser-class and the Cunard sisters. This was the only significant innovation in a room that several industry experts dismissed as conventional almost to the point of staid. One admittedly biased observer was Leonard Peskett, designer of the Lusitania and Mauretania, whose disapproval was laced with a vigorous dose of delight when he saw the near-identical Dining Saloon during his tour of the Olympic in 1911. The Titanic’s Dining Saloon may have been the largest room afloat but it was not, by any stretch of the imagination, the finest, at least not in Peskett’s view or that of many of his colleagues, especially when compared to the two-storeyed domed Rococo equivalent on the Lusitania.[fn1] There was also a problem of over-heating caused by the Saloon’s 404 light bulbs, although the chill outside meant that this was unlikely to be a problem on 10 April.[53]

Stewards served the first course on the fine bone-china plates, edged with 22-carat gold and bearing the White Star logo at the centre, setting them down amid the small forest of silver-plated cutlery, while water was poured and wine decanted into crystal glassware.[54] At ten minutes past eight, some diners began to debate when they would leave Cherbourg; their Steward leaned in to inform them politely, ‘We have been outside the breakwater for more than ten minutes, Sir.’[55]

5

A Safe Harbour for Ships

And doesn’t old Cobh look charming there

Watching the wild waves’ motion,

Leaning her back up against the hills,

And the tip of her toes in the ocean.

John Locke, ‘Morning on the Irish Coast’ (1877)

TO REDUCE THE DELAY CAUSED BY THE LONDON BOAT trains and then by the New York, the Titanic’s speed was increased as she made her night-time crossing of the Celtic Sea from France to Ireland.[1] Twenty of her twenty-nine boilers were eventually operational that evening, during which the Captain stayed on the Bridge, rather than make an appearance at his table in the Dining Saloon.[2] He did not, apparently, miss much. Even the smoothest of travel days are liable to produce their own special brand of fatigue and many passengers retired early, abandoning the Titanic’s main after-dinner haunts like the Reception and the Lounge, three decks above, long before their respective closing times of 11 and 11.30 p.m.[3] One passenger recalled later that their day had been spent ‘unpacking, making the cabin homelike, getting the lay of the public rooms, trying to determine fore and aft, port and starboard [and] getting the feel of the ship … many passengers are so exhausted with farewell parties and preparations for the voyage’.[4]

At bedtime, those who wanted a restored shine on their shoes left them to be collected from the stateroom corridors, a service that was not required by Ida Straus’s husband as he was travelling with his own valet, Farthing, a man with several years’ service to the Strauses.[5] Such familiarity was not yet possible for Ida with her maid, Ellen Bird, who had celebrated her thirty-first birthday two days earlier while packing for a new chapter of her life, in America, after Ida’s maid, Marie, had quit to marry a barber she had met during the Strauses’ winter holiday on the French Riviera. The weeks during which Marie served out her notice had not apparently been pleasant for anyone involved and the normally magnanimous Isidor was offended on his wife’s behalf since, as Ida told a relative, Marie had begun ‘behaving very badly over here. When Papa sours on a girl you know there is good cause, and he is disgusted with her.’[6] She had intended to replace Marie with another French lady’s maid, but none could be found by the time the couple left for Britain, where, after another was retained and quit upon changing her mind about moving to America, Ida had hired Ellen on the recommendation of the housekeeper at Claridge’s, their hotel during their London stay. Like the Countess of Rothes’ maid, Cissy Maioni, Ellen came from a family with a history in domestic service and she had been a maid in various households since her early twenties. Although Ida remained worried, as she had been with Marie, about ‘whether I can count on her’, so far she was pleased with Ellen, whom she described in a letter home as a ‘nice English girl’.[7] Ellen helped prepare Ida for bed, then left for her own cabin which was in First Class and on the same corridor as the Strauses’.[8]

The Strauses’ bedroom, located between their parlour and private bathrooms, was decorated in the style of the First Napoleonic Empire, to which any curve left ungilded was regarded as a curve wasted. They slept in two single beds on opposite sides of the room, separated by the door to the parlour and a marble washstand; there was a dressing table on the other side of the room, along the wall that led to their wardrobe and bathrooms. At sea, as on land, many upper-class couples had separate bedrooms and so to put them in a double bed when they were travelling was considered infra dig. The Strauses’ decision to share a cabin, if not a bed, thus emphasises their closeness rather than the opposite. They had shared a room on their previous crossing on the seven-year-old Caronia, which still had bunk beds in some of its best first-class accommodation. Isidor had taken the top berth and, one morning after he had risen, its corner fell missing Ida’s head by inches. The ship’s Purser attributed its collapse to ‘some peculiar bend or twist of the ship’, although the fact that bunks existed at all on the Caronia showed how far ocean liners’ accommodation had evolved in a relatively short period.[9]

Their mattresses on the Titanic were firm, on the instructions of J. Bruce Ismay who had ordered a change throughout First Class after sailing on the maiden voyage of the Olympic, when he had observed, ‘The only trouble of any consequence on board the ship arose from the springs of the bed being too “springy”; this, in conjunction with the spring mattresses, accentuated the pulsation in the ship to such an extent as to seriously interfere with passengers sleeping.’[10] All first-class cabins were located amidships, where the ship was most stable, but this was also directly above, albeit far above, most of her elephantine engines, hence Ismay’s insistence on a new type of bedding to cushion any vibrations when the Titanic ran at high speed, as she incrementally began to do after Cherbourg. That evening, the extinguishing of the lamps installed over most of the Titanic’s first-class beds left a nocturnal gloom gently pierced by the glow from the electric heaters provided in every stateroom. The cold in London and the breeze in Cherbourg had followed the Titanic and combined to strengthen.[11] In cabins with portholes or windows, even if closed and latched, the chill was felt to some degree and so the heaters hummed in successful combat.[12] Fortunately, even as the wind whistled around their temporary home, few of the Titanic’s inhabitants experienced seasickness – she remained on an even keel.[fn1] As one of them put it a few days later, they slept contentedly thanks to ‘the lordly contempt of the Titanic for anything less than a hurricane’.[13]

This beacon of lordly contempt was sailing between Land’s End in Cornwall and the Scilly Isles when the sun rose through broken clouds; around the same time, nearly fifty of the ship’s clocks swung in silent unison from about 5.40 to 5.15 a.m.[14] As the ship sailed westward, two master clocks in her Chart Room, both displaying time to the second, were adjusted for the crossing of the time zones. Clocks throughout the crew’s quarters and the passengers’ public rooms were linked to these master clocks and adjusted automatically with them. Known as the Magneta system, it did away with the need for crew members to move through the ship manually adjusting individual timepieces.[15] Usually the reclaiming of an hour was calculated and implemented for about midnight during the voyage, but in 1912 Ireland operated under Dublin Mean Time, twenty-five minutes behind Greenwich, and the Titanic did not clear English waters until sunrise or shortly after.[fn2] As the ship awoke, a small battalion of stewards and stewardesses brought morning tea to the staterooms or breakfast trays for those, like Ida Straus, who had the option of taking the first meal of the day in their private parlours.[16] For the rest, the Dining Saloon revived for a two-hour window, beginning at eight o’clock.[17]

*

Shortly after breakfast, south-eastern Ireland came into view with ‘the brilliant morning sun showing up the green hillsides and picking out groups of dwellings dotted here and there above the rugged grey cliffs that fringed the coast’, according to one passenger’s memoirs.[18] The port they were heading for had first been referred to as ‘the Cove of Cork’, its nearest city, in the middle of the eighteenth century, which had inspired the town’s subsequent name of Cóbh, an Irish rendering of the English ‘cove’ and pronounced in the same way.[19] Following a visit by the young Queen Victoria in 1849, Cóbh had been rechristened Queenstown. However, opponents of the Union with Britain continued to refer to the town by its pre-Victorian name, which was legally restored following Irish independence in the 1920s. Queenstown’s motto, Statio Fidissima Classi (‘A Safe Harbour for Ships’), reflected its long history as a busy port, particularly as it became the main boarding point for the millions who emigrated from Ireland in the nineteenth century. By 1912, the Irish diaspora to America had slowed to a steady trickle compared to the anguished flood of previous decades and the Titanic’s call at Queenstown had more to do with fulfilling the obligations of White Star’s mail contract, through which the ship gained her prestigious prefix of RMS, or Royal Mail Steamer.[20]

Ports like Liverpool, New York and Southampton had frequently been dredged to accommodate the recent leaps in liner size, but Queenstown, like Cherbourg, still relied on tenders. The Ireland and the America beetled out into waters turned a murky brown as the seabed sand was churned to the surface by the Titanic’s slowing propellers.[21] Sacks of mail, luggage and 191 new passengers were moved from tenders to ship, while those taking the air on the Titanic’s Boat or Promenade decks joked about the seemingly minuscule size of the ferries, ‘tossing up and down like corks’ in the swell.[22] Many admired the view of Queenstown, particularly the turrets, buttresses and 300-foot spire of its Catholic cathedral, St Colman’s, a generation-long endeavour then seven years from completion.[23] This idyllic vista, particularly the green hills hugging Queenstown and running to the shore, justified Ireland’s nickname as the Emerald Isle, a phrase allegedly first committed to paper by one of Tommy Andrews’ maternal ancestors, the republican writer William Drennan, who had, to the embarrassment of his Edwardian descendants, sided with the ill-fated 1798 rebellion against the Crown and launched the famous moniker in his poem, ‘When Erin First Rose’.[24]

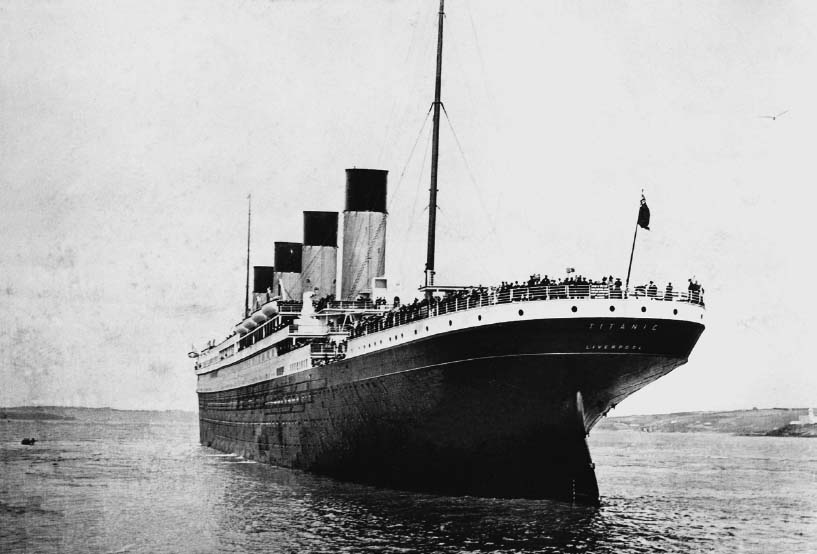

At anchor off Queenstown: many of the passengers visible on the stern were Irish immigrants who had boarded the Titanic in Third Class that morning.

The Titanic at anchor in Queenstown (Cóbh), photographed by Father Francis Browne, SJ, 11 April 1912 (Science and Society Picture Library/Father Browne Collection)

The stop at Queenstown vacated cabin A-37, directly opposite Andrews’ A-36 and occupied by a devout Irish Catholic, thirty-two-year-old Francis Browne, a charming amateur photographer who had gone to boarding school with James Joyce and was later immortalised as ‘Mr Browne the Jesuit’ in Joyce’s novel Finnegans Wake.[25] Browne evidently had not lost his ability to make an impression, since at dinner the previous evening two of his companions in the Saloon, a wealthy couple from New York, had been so captivated by his eloquence that they offered to pay his fare if he wished to remain on the ship and at their table until America. Browne, who was reading Theology in Dublin with the aim of pursuing a vocation as a priest, had to ask his superior for the necessary permission to miss his studies for a few weeks. He received a sharply worded reply in telegram form, ‘Get off that ship’.[26] Had the Jesuit professor reached the opposite decision, Andrews might have grown accustomed to seeing Browne’s face throughout the voyage. As it was, the trainee priest was up as early as the ship’s designer to snap away on his camera, mostly in the better lighting provided on the Boat Deck.[27]

Andrews’ morning produced less picturesque sights, particularly through his inspection of the watertight doors between the ship’s subterranean boiler rooms.[28] The doors had already been repeatedly tested in Belfast, but a subsequent trial at sea was considered sensible. Almost in unison, the heavy mechanised doors slid into place, sealing the Titanic’s sixteen watertight compartments off from one another, as they would if the hull was ever breached. Joined by the ship’s Chief Officer, Henry Wilde, Andrews then watched to see if the crew could open and close the watertight doors manually with a large specially purposed spanner, in the event of the failure of the doors’ electric controls operated from the Bridge. This too was successfully executed, removing another item from Andrews’ and Wilde’s to-do list.[29] The latter’s posting to the Titanic had been very much last minute and it was attributed to his service in the same role on the Olympic, where he had been liked and trusted by Captain Smith, who had also been transferred to the Titanic. It may have been Smith’s friendship that prompted Wilde’s appointment only seven days before the Titanic sailed from Southampton, bumping William Murdoch down to First Officer and Charles Lightoller to Second. There were six officer posts on the Titanic, but since the Third Officer’s task functioned largely as an apprenticeship to serving as Second Officer, this meant the previous Second Officer, David Blair, had become surplus to requirements upon Wilde’s arrival. Wilde, who preferred the Olympic and said he had a ‘queer feeling’ about the Titanic, was no more happy at being summoned than Blair was at leaving ‘a magnificent ship. I feel very disappointed I am not to make the first voyage.’[30] This reshuffling of command had an important, if subsequently exaggerated, impact in the Crow’s Nest, the vantage point on the forward mast. As theirs had not yet arrived, Blair had offered to lend the lookouts his binoculars, which he innocently took with him when he left. When this was brought to Wilde’s attention, he hunted around the ship but there did not seem to be any permanent spare pair to loan to the Crow’s Nest for the duration of the voyage. Some of the lookouts refused to let the matter drop and approached Second Officer Lightoller, around the time the ship reached Queenstown. Lightoller agreed that binoculars would be helpful and went searching for an extra set, though with the same lack of success as Wilde. Other crew members, however, thought the lookouts were creating a fuss over nothing, that one’s eyes ought to be sharp enough to do without them or that binoculars would be a hindrance rather than an aid, since they might seduce a lookout into a sense of complacency or encourage undue focus on a far away point at the expense of more immediate dangers.